Health breakthroughs of 2022 that should have made bigger news

Nine experts break down the biggest biotech and health breakthroughs that didn't get the attention they deserved in 2022.

As the world has attempted to move on from COVID-19 in 2022, attention has returned to other areas of health and biotech with major regulatory approvals such as the Alzheimer's drug lecanemab – which can slow the destruction of brain cells in the early stages of the disease – being hailed by some as momentous breakthroughs.

This has been a year where psychedelic medicines have gained the attention of mainstream researchers with a groundbreaking clinical trial showing that psilocybin treatment can help relieve some of the symptoms of major depressive disorder. And with messenger RNA (mRNA) technology still very much capturing the imagination, the readouts of cancer vaccine trials have made headlines around the world.

But at the same time there have been vital advances which will likely go on to change medicine, and yet have slipped beneath the radar. I asked nine forward-thinking experts on health and biotech about the most important, but underappreciated, breakthrough of 2022.

Their descriptions, below, were lightly edited by Leaps.org for style and format.

New drug targets for Alzheimer’s disease

Professor Julie Williams, Director, Dementia Research Institute, Cardiff University

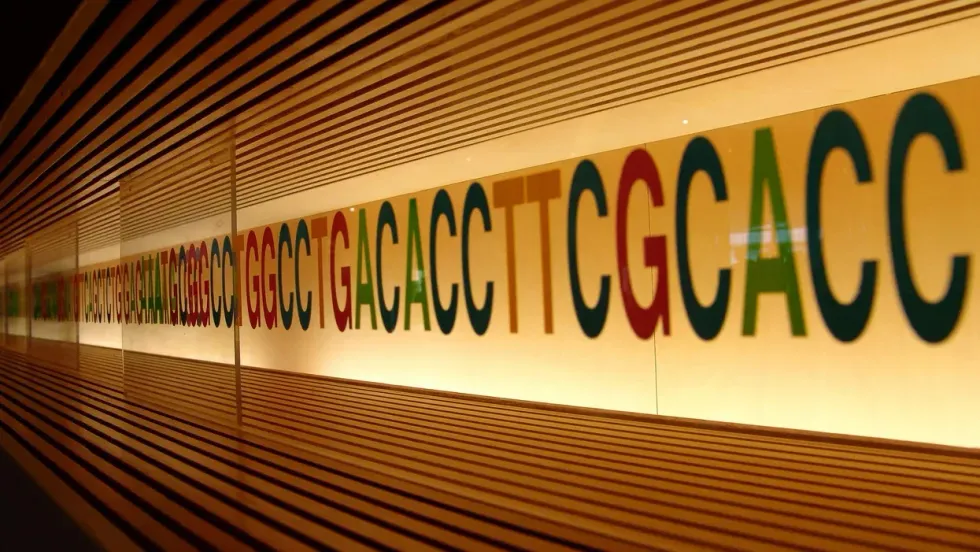

Genetics has changed our view of Alzheimer’s disease in the last five to six years. The beta amyloid hypothesis has dominated Alzheimer’s research for a long time, but there are multiple components to this complex disease, of which getting rid of amyloid plaques is one, but it is not the whole story. In April 2022, Nature published a paper which is the culmination of a decade’s worth of work - groups all over the world working together to identify 75 genes associated with risk of developing Alzheimer’s. This provides us with a roadmap for understanding the disease mechanisms.

For example, it is showing that there is something different about the immune systems of people who develop Alzheimer’s disease. There is something different about the way they process lipids in the brain, and very specific processes of how things travel through cells called endocytosis. When it comes to immunity, it indicates that the complement system is affecting whether synapses, which are the connections between neurons, get eliminated or not. In Alzheimer’s this process is more severe, so patients are losing more synapses, and this is correlated with cognition.

The genetics also implicates very specific tissues like microglia, which are the housekeepers in the brain. One of their functions is to clear away beta amyloid, but they also prune and nibble away at parts of the brain that are indicated to be diseased. If you have these risk genes, it seems that you are likely to prune more tissue, which may be part of the cell death and neurodegeneration that we observe in Alzheimer’s patients.

Genetics is telling us that we need to be looking at multiple causes of this complex disease, and we are doing that now. It is showing us that there are a number of different processes which combine to push patients into a disease state which results in the death of connections between nerve cells. These findings around the complement system and other immune-related mechanisms are very interesting as there are already drugs which are available for other diseases which could be repurposed in clinical trials. So it is really a turning point for us in the Alzheimer’s disease field.

Preventing Pandemics with Organ-Tissue Equivalents

Anthony Atala, Director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine

COVID-19 has shown us that we need to be better prepared ahead of future pandemics and have systems in place where we can quickly catalogue a new virus and have an idea of which treatment agents would work best against it.

At Wake Forest Institute, our scientists have developed what we call organ-tissue equivalents. These are miniature tissues and organs, created using the same regenerative medicine technologies which we have been using to create tissues for patients. For example, if we are making a miniature liver, we will recreate this structure using the six different cell types you find in the liver, in the right proportions, and then the right extracellular matrix which holds the structure together. You're trying to replicate all the characteristics of the liver, but just in a miniature format.

We can now put these organ-tissue equivalents in a chip-like device, where we can expose them to different types of viral infections, and start to get a realistic idea of how the human body reacts to these viruses. We can use artificial intelligence and machine learning to map the pathways of the body’s response. This will allow us to catalogue known viruses far more effectively, and begin storing information on them.

Powering Deep Brain Stimulators with Breath

Islam Mosa, Co-Founder and CTO of VoltXon

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices are becoming increasingly common with 150,000 new devices being implanted every year for people with Parkinson’s disease, but also psychiatric conditions such as treatment-resistant depression and obsessive-compulsive disorders. But one of the biggest limitations is the power source – I call DBS devices energy monsters. While cardiac pacemakers use similar technology, their batteries last seven to ten years, but DBS batteries need changing every two to three years. This is because they are generating between 60-180 pulses per second.

Replacing the batteries requires surgery which costs a lot of money, and with every repeat operation comes a risk of infection, plus there is a lot of anxiety on behalf of the patient that the battery is running out.

My colleagues at the University of Connecticut and I, have developed a new way of charging these devices using the person’s own breathing movements, which would mean that the batteries never need to be changed. As the patient breathes in and out, their chest wall presses on a thin electric generator, which converts that movement into static electricity, charging a supercapacitor. This discharges the electricity required to power the DBS device and send the necessary pulses to the brain.

So far it has only been tested in a simulated pig, using a pig lung connected to a pump, but there are plans now to test it in a real animal, and then progress to clinical trials.

Smartwatches for Disease Detection

Jessilyn Dunn, Assistant Professor in Duke Biomedical Engineering

A group of researchers recently showed that digital biomarkers of infection can reveal when someone is sick, often before they feel sick. The team, which included Duke biomedical engineers, used information from smartwatches to detect Covid-19 cases five to 10 days earlier than diagnostic tests. Smartwatch data included aspects of heart rate, sleep quality and physical activity. Based on this data, we developed an algorithm to decide which people have the most need to take the diagnostic tests. With this approach, the percent of tests that come back positive are about four- to six-times higher, depending on which factors we monitor through the watches.

Our study was one of several showing the value of digital biomarkers, rather than a single blockbuster paper. With so many new ideas and technologies coming out around Covid, it’s hard to be that signal through the noise. More studies are needed, but this line of research is important because, rather than treat everyone as equally likely to have an infectious disease, we can use prior knowledge from smartwatches. With monkeypox, for example, you've got many more people who need to be tested than you have tests available. Information from the smartwatches enables you to improve how you allocate those tests.

Smartwatch data could also be applied to chronic diseases. For viruses, we’re looking for information about anomalies – a big change point in people’s health. For chronic diseases, it’s more like a slow, steady change. Our research lays the groundwork for the signals coming from smartwatches to be useful in a health setting, and now it’s up to us to detect more of these chronic cases. We want to go from the idea that we have this single change point, like a heart attack or stroke, and focus on the part before that, to see if we can detect it.

A Vaccine For RSV

Norbert Pardi, Vaccines Group Lead, Penn Institute for RNA Innovation, University of Pennsylvania

Scientists have long been trying to develop a vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and it looks like Pfizer are closing in on this goal, based on the latest clinical trial data in newborns which they released in November. Pfizer have developed a protein-based vaccine against the F protein of RSV, which they are giving to pregnant women. It turns out that it induces a robust immune response after the administration of a single shot and it seems to be highly protective in newborns. The efficacy was over 80% after 90 days, so it protected very well against severe disease, and even though this dropped a little after six month, it was still pretty high.

I think this has been a very important breakthrough, and very timely at the moment with both COVID-19, influenza and RSV circulating, which just shows the importance of having a vaccine which works well in both the very young and the very old.

The road to an RSV vaccine has also illustrated the importance of teamwork in 21st century vaccine development. You need people with different backgrounds to solve these challenges – microbiologists, immunologists and structural biologists working together to understand how viruses work, and how our immune system induces protective responses against certain viruses. It has been this kind of teamwork which has yielded the findings that targeting the prefusion stabilized form of the F protein in RSV induces much stronger and highly protective immune responses.

Gene therapy shows its potential

Nicole Paulk, Assistant Professor of Gene Therapy at the University of California, San Francisco

The recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Hemgenix, a gene therapy for hemophilia B, is big for a lot of reasons. While hemophilia is absolutely a rare disease, it is astronomically more common than the first two approvals – Luxturna for RPE65-meidated inherited retinal dystrophy and Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy - so many more patients will be treated with this. In terms of numbers of patients, we are now starting to creep up into things that are much more common, which is a huge step in terms of our ability to scale the production of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector for gene therapy.

Hemophilia is also a really special patient population because this has been the darling indication for AAV gene therapy for the last 20 to 30 years. AAV trafficks to the liver so well, it’s really easy for us to target the tissues that we want. If you look at the numbers, there have been more gene therapy scientists working on hemophilia than any other condition. There have just been thousands and thousands of us working on gene therapy indications for the last 20 or 30 years, so to see the first of these approvals make it, feels really special.

I am sure it is even more special for the patients because now they have a choice – do I want to stay on my recombinant factor drug that I need to take every day for the rest of my life, or right now I could get a one-time infusion of this virus and possibly experience curative levels of expression for the rest of my life. And this is just the first one for hemophilia, there’s going to end up being a dozen gene therapies within the next five years, targeted towards different hemophilias.

Every single approval is momentous for the entire field because it gets investors excited, it gets companies and physicians excited, and that helps speed things up. Right now, it's still a challenge to produce enough for double digit patients. But with more interest comes the experiments and trials that allow us to pick up the knowledge to scale things up, so that we can go after bigger diseases like diabetes, congestive heart failure, cancer, all of these much bigger afflictions.

Treating Thickened Hearts

John Spertus, Professor in Metabolic and Vascular Disease Research, UMKC School of Medicine

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease that causes your heart muscle to enlarge, and the walls of your heart chambers thicken and reduce in size. Because of this, they cannot hold as much blood and may stiffen, causing some sufferers to experience progressive shortness of breath, fatigue and ultimately heart failure.

So far we have only had very crude ways of treating it, using beta blockers, calcium channel blockers or other medications which cause the heart to beat less strongly. This works for some patients but a lot of time it does not, which means you have to consider removing part of the wall of the heart with surgery.

Earlier this year, a trial of a drug called mavacamten, became the first study to show positive results in treating HCM. What is remarkable about mavacamten is that it is directed at trying to block the overly vigorous contractile proteins in the heart, so it is a highly targeted, focused way of addressing the key problem in these patients. The study demonstrated a really large improvement in patient quality of life where they were on the drug, and when they went off the drug, the quality of life went away.

Some specialists are now hypothesizing that it may work for other cardiovascular diseases where the heart either beats too strongly or it does not relax well enough, but just having a treatment for HCM is a really big deal. For years we have not been very aggressive in identifying and treating these patients because there have not been great treatments available, so this could lead to a new era.

Regenerating Organs

David Andrijevic, Associate Research Scientist in neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine

As soon as the heartbeat stops, a whole chain of biochemical processes resulting from ischemia – the lack of blood flow, oxygen and nutrients – begins to destroy the body’s cells and organs. My colleagues and I at Yale School of Medicine have been investigating whether we can recover organs after prolonged ischemia, with the main goal of expanding the organ donor pool.

Earlier this year we published a paper in which we showed that we could use technology to restore blood circulation, other cellular functions and even heart activity in pigs, one hour after their deaths. This was done using a perfusion technology to substitute heart, lung and kidney function, and deliver an experimental cell protective fluid to these organs which aimed to stop cell death and aid in the recovery.

One of the aims of this technology is that it can be used in future to lengthen the time window for recovering organs for donation after a person has been declared dead, a logistical hurdle which would allow us to substantially increase the donor pool. We might also be able to use this cell protective fluid in studies to see if it can help people who have suffered from strokes and myocardial infarction. In future, if we managed to achieve an adequate brain recovery – and the brain, out of all the organs, is the most susceptible to ischemia – this might also change some paradigms in resuscitation medicine.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer

Yosi Shamay, Cancer Nanomedicine and Nanoinformatics researcher at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology

For the past four or five years, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) - a cancer drug where you have an antibody conjugated to a toxin - have been used only in patients with specific cancers that display high expression of a target protein, for example HER2-positive breast cancer. But in 2022, there have been clinical trials where ADCs have shown remarkable results in patients with low expression of HER2, which is something we never expected to see.

In July 2022, AstraZeneca published the results of a clinical trial, which showed that an ADC called trastuzumab deruxtecan can offer a very big survival benefit to breast cancer patients with very little expression of HER2, levels so low that they would be borderline undetectable for a pathologist. They got a strong survival signal for patients with very aggressive, metastatic disease.

I think this is very interesting and important because it means that it might pave the way to include more patients in clinical trials looking at ADCs for other cancers, for example lymphoma, colon cancer, lung cancers, even if they have low expression of the protein target. It also holds implications for CAR-T cells - where you genetically engineer a T cell to attack the cancer - because the concept is very similar. If we now know that an ADC can have a survival benefit, even in patients with very low target expression, the same might be true for T cells.

Look back further: Breakthroughs of 2021

https://leaps.org/6-biotech-breakthroughs-of-2021-that-missed-the-attention-they-deserved/

Real-Time Monitoring of Your Health Is the Future of Medicine

Implantable sensors and other surveillance technologies offer tremendous health benefits -- and ethical challenges.

The same way that it's harder to lose 100 pounds than it is to not gain 100 pounds, it's easier to stop a disease before it happens than to treat an illness once it's developed.

In Morris' dream scenario "everyone will be implanted with a sensor" ("…the same way most people are vaccinated") and the sensor will alert people to go to the doctor if something is awry.

Bio-engineers working on the next generation of diagnostic tools say today's technology, such as colonoscopies or mammograms, are reactionary; that is, they tell a person they are sick often when it's too late to reverse course. Surveillance medicine — such as implanted sensors — will detect disease at its onset, in real time.

What Is Possible?

Ever since the Human Genome Project — which concluded in 2003 after mapping the DNA sequence of all 30,000 human genes — modern medicine has shifted to "personalized medicine." Also called, "precision health," 21st-century doctors can in some cases assess a person's risk for specific diseases from his or her DNA. The information enables women with a BRCA gene mutation, for example, to undergo more frequent screenings for breast cancer or to pro-actively choose to remove their breasts, as a "just in case" measure.

But your DNA is not always enough to determine your risk of illness. Not all genetic mutations are harmful, for example, and people can get sick without a genetic cause, such as with an infection. Hence the need for a more "real-time" way to monitor health.

Aaron Morris, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Michigan, wants doctors to be able to predict illness with pinpoint accuracy well before symptoms show up. Working in the lab of Dr. Lonnie Shea, the team is building "a tiny diagnostic lab" that can live under a person's skin and monitor for illness, 24/7. Currently being tested in mice, the Michigan team's porous biodegradable implant becomes part of the body as "cells move right in," says Morris, allowing engineered tissue to be biopsied and analyzed for diseases. The information collected by the sensors will enable doctors to predict disease flareups, such as for cancer relapses, so that therapies can begin well before a person comes out of remission. The technology will also measure the effectiveness of those therapies in real time.

In Morris' dream scenario "everyone will be implanted with a sensor" ("…the same way most people are vaccinated") and the sensor will alert people to go to the doctor if something is awry.

While it may be four or five decades before Morris' sensor becomes mainstream, "the age of surveillance medicine is here," says Jamie Metzl, a technology and healthcare futurist who penned Hacking Darwin: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity. "It will get more effective and sophisticated and less obtrusive over time," says Metzl.

Already, Google compiles public health data about disease hotspots by amalgamating individual searches for medical symptoms; pill technology can digitally track when and how much medication a patient takes; and, the Apple watch heart app can predict with 85-percent accuracy if an individual using the wrist device has Atrial Fibrulation (AFib) — a condition that causes stroke, blood clots and heart failure, and goes undiagnosed in 700,000 people each year in the U.S.

"We'll never be able to predict everything," says Metzl. "But we will always be able to predict and prevent more and more; that is the future of healthcare and medicine."

Morris believes that within ten years there will be surveillance tools that can predict if an individual has contracted the flu well before symptoms develop.

At City College of New York, Ryan Williams, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, has built an implantable nano-sensor that works with a florescent wand to scope out if cancer cells are growing at the implant site. "Instead of having the ovary or breast removed, the patient could just have this [surveillance] device that can say 'hey we're monitoring for this' in real-time… [to] measure whether the cancer is maybe coming back,' as opposed to having biopsy tests or undergoing treatments or invasive procedures."

Not all surveillance technologies that are being developed need to be implanted. At Case Western, Colin Drummond, PhD, MBA, a data scientist and assistant department chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, is building a "surroundable." He describes it as an Alexa-style surveillance system (he's named her Regina) that will "tell" the user, if a need arises for medication, how much to take and when.

Bioethical Red Flags

"Everyone should be extremely excited about our move toward what I call predictive and preventive health care and health," says Metzl. "We should also be worried about it. Because all of these technologies can be used well and they can [also] be abused." The concerns are many layered:

Discriminatory practices

For years now, bioethicists have expressed concerns about employee-sponsored wellness programs that encourage fitness while also tracking employee health data."Getting access to your health data can change the way your employer thinks about your employability," says Keisha Ray, assistant professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). Such access can lead to discriminatory practices against employees that are less fit. "Surveillance medicine only heightens those risks," says Ray.

Who owns the data?

Surveillance medicine may help "democratize healthcare" which could be a good thing, says Anita Ho, an associate professor in bioethics at both the University of California, San Francisco and at the University of British Columbia. It would enable easier access by patients to their health data, delivered to smart phones, for example, rather than waiting for a call from the doctor. But, she also wonders who will own the data collected and if that owner has the right to share it or sell it. "A direct-to-consumer device is where the lines get a little blurry," says Ho. Currently, health data collected by Apple Watch is owned by Apple. "So we have to ask bigger ethical questions in terms of what consent should be required" by users.

Insurance coverage

"Consumers of these products deserve some sort of assurance that using a product that will predict future needs won't in any way jeopardize their ability to access care for those needs," says Hastings Center bioethicist Carolyn Neuhaus. She is urging lawmakers to begin tackling policy issues created by surveillance medicine, now, well ahead of the technology becoming mainstream, not unlike GINA, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 -- a federal law designed to prevent discrimination in health insurance on the basis of genetic information.

And, because not all Americans have insurance, Ho wants to know, who's going to pay for this technology and how much will it cost?

Trusting our guts

Some bioethicists are concerned that surveillance technology will reduce individuals to their "risk profiles," leaving health care systems to perceive them as nothing more than a "bundle of health and security risks." And further, in our quest to predict and prevent ailments, Neuhaus wonders if an over-reliance on data could damage the ability of future generations to trust their gut and tune into their own bodies?

It "sounds kind of hippy-dippy and feel-goodie," she admits. But in our culture of medicine where efficiency is highly valued, there's "a tendency to not value and appreciate what one feels inside of their own body … [because] it's easier to look at data than to listen to people's really messy stories of how they 'felt weird' the other day. It takes a lot less time to look at a sheet, to read out what the sensor implanted inside your body or planted around your house says."

Ho, too, worries about lost narratives. "For surveillance medicine to actually work we have to think about how we educate clinicians about the utility of these devices and how to how to interpret the data in the broader context of patients' lives."

Over-diagnosing

While one of the goals of surveillance medicine is to cut down on doctor visits, Ho wonders if the technology will have the opposite effect. "People may be going to the doctor more for things that actually are benign and are really not of concern yet," says Ho. She is also concerned that surveillance tools could make healthcare almost "recreational" and underscores the importance of making sure that the goals of surveillance medicine are met before the technology is unleashed.

"We can't just assume that any of these technologies are inherently technologies of liberation."

AI doesn't fix existing healthcare problems

"Knowing that you're going to have a fall or going to relapse or have a disease isn't all that helpful if you have no access to the follow-up care and you can't afford it and you can't afford the prescription medication that's going to ward off the onset," says Neuhaus. "It may still be worth knowing … but we can't fool ourselves into thinking that this technology is going to reshape medicine in America if we don't pay attention to … the infrastructure that we don't currently have."

Race-based medicine

How surveillances devices are tested before being approved for human use is a major concern for Ho. In recent years, alerts have been raised about the homogeneity of study group participants — too white and too male. Ho wonders if the devices will be able to "accurately predict the disease progression for people whose data has not been used in developing the technology?" COVID-19 has killed Black people at a rate 2.5 time greater than white people, for example, and new, virtual clinical research is focused on recruiting more people of color.

The Biggest Question

"We can't just assume that any of these technologies are inherently technologies of liberation," says Metzl.

Especially because we haven't yet asked the 64-thousand dollar question: Would patients even want to know?

Jenny Ahlstrom is an IT professional who was diagnosed at 43 with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that typically attacks people in their late 60s and 70s and for which there is no cure. She believes that most people won't want to know about their declining health in real time. People like to live "optimistically in denial most of the time. If they don't have a problem, they don't want to really think they have a problem until they have [it]," especially when there is no cure. "Psychologically? That would be hard to know."

Ahlstrom says there's also the issue of trust, something she experienced first-hand when she launched her non-profit, HealthTree, a crowdsourcing tool to help myeloma patients "find their genetic twin" and learn what therapies may or may not work. "People want to share their story, not their data," says Ahlstrom. "We have been so conditioned as a nation to believe that our medical data is so valuable."

Metzl acknowledges that adoption of new technologies will be uneven. But he also believes that "over time, it will be abundantly clear that it's much, much cheaper to predict and prevent disease than it is to treat disease once it's already emerged."

Beyond cost, the tremendous potential of these technologies to help us live healthier and longer lives is a game-changer, he says, as long as we find ways "to ultimately navigate this terrain and put systems in place ... to minimize any potential harms."

How Smallpox Was Wiped Off the Planet By a Vaccine and Global Cooperation

The world's last recorded case of endemic smallpox was in Ali Maow Maalin, of Merka, Somalia, in October 1977. He made a full recovery.

For 3000 years, civilizations all over the world were brutalized by smallpox, an infectious and deadly virus characterized by fever and a rash of painful, oozing sores.

Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success.

Smallpox was merciless, killing one third of people it infected and leaving many survivors permanently pockmarked and blind. Although smallpox was more common during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was still a leading cause of death even up until the early 1950s, killing an estimated 50 million people annually.

A Primitive Cure

Sometime during the 10th century, Chinese physicians figured out that exposing people to a tiny bit of smallpox would sometimes result in a milder infection and immunity to the disease afterward (if the person survived). Desperate for a cure, people would huff powders made of smallpox scabs or insert smallpox pus into their skin, all in the hopes of getting immunity without having to get too sick. However, this method – called inoculation – didn't always work. People could still catch the full-blown disease, spread it to others, or even catch another infectious disease like syphilis in the process.

A Breakthrough Treatment

For centuries, inoculation – however imperfect – was the only protection the world had against smallpox. But in the late 18th century, an English physician named Edward Jenner created a more effective method. Jenner discovered that inoculating a person with cowpox – a much milder relative of the smallpox virus – would make that person immune to smallpox as well, but this time without the possibility of actually catching or transmitting smallpox. His breakthrough became the world's first vaccine against a contagious disease. Other researchers, like Louis Pasteur, would use these same principles to make vaccines for global killers like anthrax and rabies. Vaccination was considered a miracle, conferring all of the rewards of having gotten sick (immunity) without the risk of death or blindness.

Scaling the Cure

As vaccination became more widespread, the number of global smallpox deaths began to drop, particularly in Europe and the United States. But even as late as 1967, smallpox was still killing anywhere from 10 to 15 million people in poorer parts of the globe. The World Health Assembly (a decision-making body of the World Health Organization) decided that year to launch the first coordinated effort to eradicate smallpox from the planet completely, aiming for 80 percent vaccine coverage in every country in which the disease was endemic – a total of 33 countries.

But officials knew that eradicating smallpox would be easier said than done. Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success. The vaccination initiative in Bangladesh proved the most challenging, due to its population density and the prevalence of the disease, writes journalist Laurie Garrett in her book, The Coming Plague.

In one instance, French physician Daniel Tarantola on assignment in Bangladesh confronted a murderous gang that was thought to be spreading smallpox throughout the countryside during their crime sprees. Without police protection, Tarantola confronted the gang and "faced down guns" in order to immunize them, protecting the villagers from repeated outbreaks.

Because not enough vaccines existed to vaccinate everyone in a given country, doctors utilized a strategy called "ring vaccination," which meant locating individual outbreaks and vaccinating all known and possible contacts to stop an outbreak at its source. Fewer than 50 percent of the population in Nigeria received a vaccine, for example, but thanks to ring vaccination, it was eradicated in that country nonetheless. Doctors worked tirelessly for the next eleven years to immunize as many people as possible.

The World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

A Resounding Success

In November 1975, officials discovered a case of variola major — the more virulent strain of the smallpox virus — in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl named Rahima Banu. Banu was forcibly quarantined in her family's home with armed guards until the risk of transmission had passed, while officials went door-to-door vaccinating everyone within a five-mile radius. Two years later, the last case of variola major in human history was reported in Somalia. When no new community-acquired cases appeared after that, the World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

Because of smallpox, we now know it's possible to completely eliminate a disease. But is it likely to happen again with other diseases, like COVID-19? Some scientists aren't so sure. As dangerous as smallpox was, it had a few characteristics that made eradication possibly easier than for other diseases. Smallpox, for instance, has no animal reservoir, meaning that it could not circulate in animals and resurge in a human population at a later date. Additionally, a person who had smallpox once was guaranteed immunity from the disease thereafter — which is not the case for COVID-19.

In The Coming Plague, Japanese physician Isao Arita, who led the WHO's Smallpox Eradication Unit, admitted to routinely defying orders from the WHO, mobilizing to parts of the world without official approval and sometimes even vaccinating people against their will. "If we hadn't broken every single WHO rule many times over, we would have never defeated smallpox," Arita said. "Never."

Still, thanks to the life-saving technology of vaccines – and the tireless efforts of doctors and scientists across the globe – a once-lethal disease is now a thing of the past.