Health breakthroughs of 2022 that should have made bigger news

Nine experts break down the biggest biotech and health breakthroughs that didn't get the attention they deserved in 2022.

As the world has attempted to move on from COVID-19 in 2022, attention has returned to other areas of health and biotech with major regulatory approvals such as the Alzheimer's drug lecanemab – which can slow the destruction of brain cells in the early stages of the disease – being hailed by some as momentous breakthroughs.

This has been a year where psychedelic medicines have gained the attention of mainstream researchers with a groundbreaking clinical trial showing that psilocybin treatment can help relieve some of the symptoms of major depressive disorder. And with messenger RNA (mRNA) technology still very much capturing the imagination, the readouts of cancer vaccine trials have made headlines around the world.

But at the same time there have been vital advances which will likely go on to change medicine, and yet have slipped beneath the radar. I asked nine forward-thinking experts on health and biotech about the most important, but underappreciated, breakthrough of 2022.

Their descriptions, below, were lightly edited by Leaps.org for style and format.

New drug targets for Alzheimer’s disease

Professor Julie Williams, Director, Dementia Research Institute, Cardiff University

Genetics has changed our view of Alzheimer’s disease in the last five to six years. The beta amyloid hypothesis has dominated Alzheimer’s research for a long time, but there are multiple components to this complex disease, of which getting rid of amyloid plaques is one, but it is not the whole story. In April 2022, Nature published a paper which is the culmination of a decade’s worth of work - groups all over the world working together to identify 75 genes associated with risk of developing Alzheimer’s. This provides us with a roadmap for understanding the disease mechanisms.

For example, it is showing that there is something different about the immune systems of people who develop Alzheimer’s disease. There is something different about the way they process lipids in the brain, and very specific processes of how things travel through cells called endocytosis. When it comes to immunity, it indicates that the complement system is affecting whether synapses, which are the connections between neurons, get eliminated or not. In Alzheimer’s this process is more severe, so patients are losing more synapses, and this is correlated with cognition.

The genetics also implicates very specific tissues like microglia, which are the housekeepers in the brain. One of their functions is to clear away beta amyloid, but they also prune and nibble away at parts of the brain that are indicated to be diseased. If you have these risk genes, it seems that you are likely to prune more tissue, which may be part of the cell death and neurodegeneration that we observe in Alzheimer’s patients.

Genetics is telling us that we need to be looking at multiple causes of this complex disease, and we are doing that now. It is showing us that there are a number of different processes which combine to push patients into a disease state which results in the death of connections between nerve cells. These findings around the complement system and other immune-related mechanisms are very interesting as there are already drugs which are available for other diseases which could be repurposed in clinical trials. So it is really a turning point for us in the Alzheimer’s disease field.

Preventing Pandemics with Organ-Tissue Equivalents

Anthony Atala, Director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine

COVID-19 has shown us that we need to be better prepared ahead of future pandemics and have systems in place where we can quickly catalogue a new virus and have an idea of which treatment agents would work best against it.

At Wake Forest Institute, our scientists have developed what we call organ-tissue equivalents. These are miniature tissues and organs, created using the same regenerative medicine technologies which we have been using to create tissues for patients. For example, if we are making a miniature liver, we will recreate this structure using the six different cell types you find in the liver, in the right proportions, and then the right extracellular matrix which holds the structure together. You're trying to replicate all the characteristics of the liver, but just in a miniature format.

We can now put these organ-tissue equivalents in a chip-like device, where we can expose them to different types of viral infections, and start to get a realistic idea of how the human body reacts to these viruses. We can use artificial intelligence and machine learning to map the pathways of the body’s response. This will allow us to catalogue known viruses far more effectively, and begin storing information on them.

Powering Deep Brain Stimulators with Breath

Islam Mosa, Co-Founder and CTO of VoltXon

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices are becoming increasingly common with 150,000 new devices being implanted every year for people with Parkinson’s disease, but also psychiatric conditions such as treatment-resistant depression and obsessive-compulsive disorders. But one of the biggest limitations is the power source – I call DBS devices energy monsters. While cardiac pacemakers use similar technology, their batteries last seven to ten years, but DBS batteries need changing every two to three years. This is because they are generating between 60-180 pulses per second.

Replacing the batteries requires surgery which costs a lot of money, and with every repeat operation comes a risk of infection, plus there is a lot of anxiety on behalf of the patient that the battery is running out.

My colleagues at the University of Connecticut and I, have developed a new way of charging these devices using the person’s own breathing movements, which would mean that the batteries never need to be changed. As the patient breathes in and out, their chest wall presses on a thin electric generator, which converts that movement into static electricity, charging a supercapacitor. This discharges the electricity required to power the DBS device and send the necessary pulses to the brain.

So far it has only been tested in a simulated pig, using a pig lung connected to a pump, but there are plans now to test it in a real animal, and then progress to clinical trials.

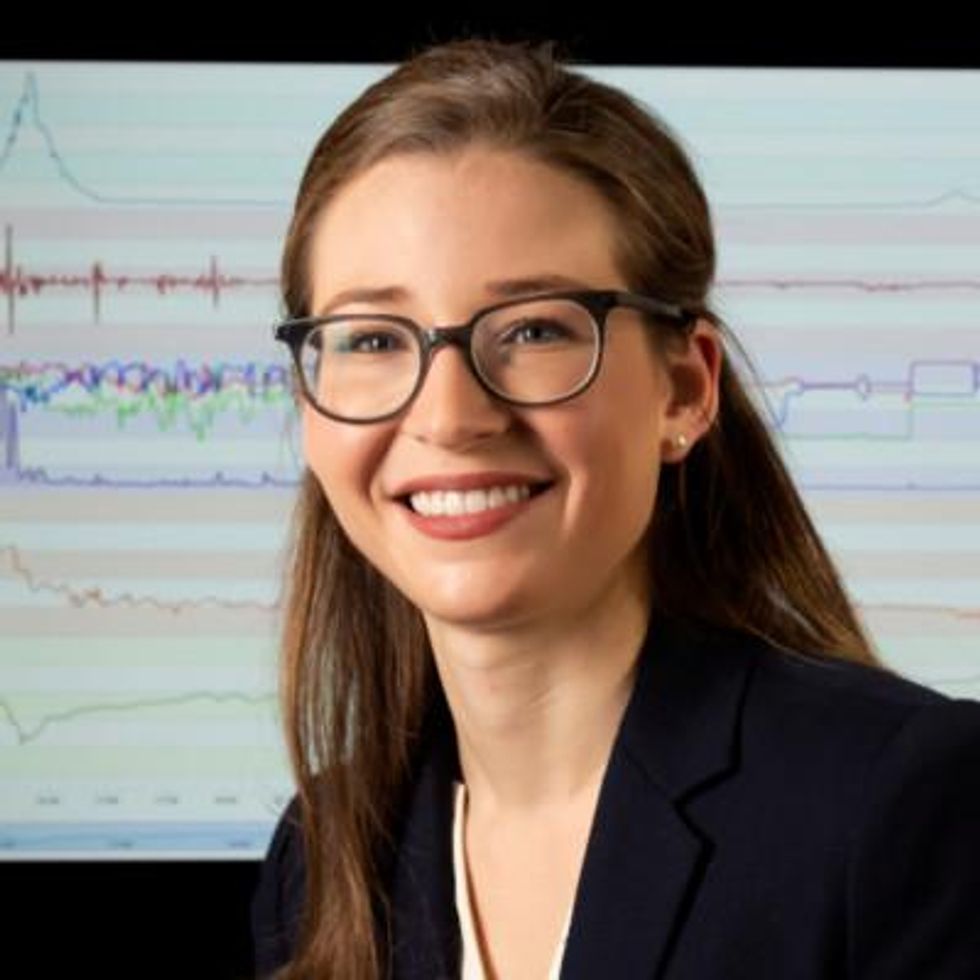

Smartwatches for Disease Detection

Jessilyn Dunn, Assistant Professor in Duke Biomedical Engineering

A group of researchers recently showed that digital biomarkers of infection can reveal when someone is sick, often before they feel sick. The team, which included Duke biomedical engineers, used information from smartwatches to detect Covid-19 cases five to 10 days earlier than diagnostic tests. Smartwatch data included aspects of heart rate, sleep quality and physical activity. Based on this data, we developed an algorithm to decide which people have the most need to take the diagnostic tests. With this approach, the percent of tests that come back positive are about four- to six-times higher, depending on which factors we monitor through the watches.

Our study was one of several showing the value of digital biomarkers, rather than a single blockbuster paper. With so many new ideas and technologies coming out around Covid, it’s hard to be that signal through the noise. More studies are needed, but this line of research is important because, rather than treat everyone as equally likely to have an infectious disease, we can use prior knowledge from smartwatches. With monkeypox, for example, you've got many more people who need to be tested than you have tests available. Information from the smartwatches enables you to improve how you allocate those tests.

Smartwatch data could also be applied to chronic diseases. For viruses, we’re looking for information about anomalies – a big change point in people’s health. For chronic diseases, it’s more like a slow, steady change. Our research lays the groundwork for the signals coming from smartwatches to be useful in a health setting, and now it’s up to us to detect more of these chronic cases. We want to go from the idea that we have this single change point, like a heart attack or stroke, and focus on the part before that, to see if we can detect it.

A Vaccine For RSV

Norbert Pardi, Vaccines Group Lead, Penn Institute for RNA Innovation, University of Pennsylvania

Scientists have long been trying to develop a vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and it looks like Pfizer are closing in on this goal, based on the latest clinical trial data in newborns which they released in November. Pfizer have developed a protein-based vaccine against the F protein of RSV, which they are giving to pregnant women. It turns out that it induces a robust immune response after the administration of a single shot and it seems to be highly protective in newborns. The efficacy was over 80% after 90 days, so it protected very well against severe disease, and even though this dropped a little after six month, it was still pretty high.

I think this has been a very important breakthrough, and very timely at the moment with both COVID-19, influenza and RSV circulating, which just shows the importance of having a vaccine which works well in both the very young and the very old.

The road to an RSV vaccine has also illustrated the importance of teamwork in 21st century vaccine development. You need people with different backgrounds to solve these challenges – microbiologists, immunologists and structural biologists working together to understand how viruses work, and how our immune system induces protective responses against certain viruses. It has been this kind of teamwork which has yielded the findings that targeting the prefusion stabilized form of the F protein in RSV induces much stronger and highly protective immune responses.

Gene therapy shows its potential

Nicole Paulk, Assistant Professor of Gene Therapy at the University of California, San Francisco

The recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Hemgenix, a gene therapy for hemophilia B, is big for a lot of reasons. While hemophilia is absolutely a rare disease, it is astronomically more common than the first two approvals – Luxturna for RPE65-meidated inherited retinal dystrophy and Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy - so many more patients will be treated with this. In terms of numbers of patients, we are now starting to creep up into things that are much more common, which is a huge step in terms of our ability to scale the production of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector for gene therapy.

Hemophilia is also a really special patient population because this has been the darling indication for AAV gene therapy for the last 20 to 30 years. AAV trafficks to the liver so well, it’s really easy for us to target the tissues that we want. If you look at the numbers, there have been more gene therapy scientists working on hemophilia than any other condition. There have just been thousands and thousands of us working on gene therapy indications for the last 20 or 30 years, so to see the first of these approvals make it, feels really special.

I am sure it is even more special for the patients because now they have a choice – do I want to stay on my recombinant factor drug that I need to take every day for the rest of my life, or right now I could get a one-time infusion of this virus and possibly experience curative levels of expression for the rest of my life. And this is just the first one for hemophilia, there’s going to end up being a dozen gene therapies within the next five years, targeted towards different hemophilias.

Every single approval is momentous for the entire field because it gets investors excited, it gets companies and physicians excited, and that helps speed things up. Right now, it's still a challenge to produce enough for double digit patients. But with more interest comes the experiments and trials that allow us to pick up the knowledge to scale things up, so that we can go after bigger diseases like diabetes, congestive heart failure, cancer, all of these much bigger afflictions.

Treating Thickened Hearts

John Spertus, Professor in Metabolic and Vascular Disease Research, UMKC School of Medicine

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease that causes your heart muscle to enlarge, and the walls of your heart chambers thicken and reduce in size. Because of this, they cannot hold as much blood and may stiffen, causing some sufferers to experience progressive shortness of breath, fatigue and ultimately heart failure.

So far we have only had very crude ways of treating it, using beta blockers, calcium channel blockers or other medications which cause the heart to beat less strongly. This works for some patients but a lot of time it does not, which means you have to consider removing part of the wall of the heart with surgery.

Earlier this year, a trial of a drug called mavacamten, became the first study to show positive results in treating HCM. What is remarkable about mavacamten is that it is directed at trying to block the overly vigorous contractile proteins in the heart, so it is a highly targeted, focused way of addressing the key problem in these patients. The study demonstrated a really large improvement in patient quality of life where they were on the drug, and when they went off the drug, the quality of life went away.

Some specialists are now hypothesizing that it may work for other cardiovascular diseases where the heart either beats too strongly or it does not relax well enough, but just having a treatment for HCM is a really big deal. For years we have not been very aggressive in identifying and treating these patients because there have not been great treatments available, so this could lead to a new era.

Regenerating Organs

David Andrijevic, Associate Research Scientist in neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine

As soon as the heartbeat stops, a whole chain of biochemical processes resulting from ischemia – the lack of blood flow, oxygen and nutrients – begins to destroy the body’s cells and organs. My colleagues and I at Yale School of Medicine have been investigating whether we can recover organs after prolonged ischemia, with the main goal of expanding the organ donor pool.

Earlier this year we published a paper in which we showed that we could use technology to restore blood circulation, other cellular functions and even heart activity in pigs, one hour after their deaths. This was done using a perfusion technology to substitute heart, lung and kidney function, and deliver an experimental cell protective fluid to these organs which aimed to stop cell death and aid in the recovery.

One of the aims of this technology is that it can be used in future to lengthen the time window for recovering organs for donation after a person has been declared dead, a logistical hurdle which would allow us to substantially increase the donor pool. We might also be able to use this cell protective fluid in studies to see if it can help people who have suffered from strokes and myocardial infarction. In future, if we managed to achieve an adequate brain recovery – and the brain, out of all the organs, is the most susceptible to ischemia – this might also change some paradigms in resuscitation medicine.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer

Yosi Shamay, Cancer Nanomedicine and Nanoinformatics researcher at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology

For the past four or five years, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) - a cancer drug where you have an antibody conjugated to a toxin - have been used only in patients with specific cancers that display high expression of a target protein, for example HER2-positive breast cancer. But in 2022, there have been clinical trials where ADCs have shown remarkable results in patients with low expression of HER2, which is something we never expected to see.

In July 2022, AstraZeneca published the results of a clinical trial, which showed that an ADC called trastuzumab deruxtecan can offer a very big survival benefit to breast cancer patients with very little expression of HER2, levels so low that they would be borderline undetectable for a pathologist. They got a strong survival signal for patients with very aggressive, metastatic disease.

I think this is very interesting and important because it means that it might pave the way to include more patients in clinical trials looking at ADCs for other cancers, for example lymphoma, colon cancer, lung cancers, even if they have low expression of the protein target. It also holds implications for CAR-T cells - where you genetically engineer a T cell to attack the cancer - because the concept is very similar. If we now know that an ADC can have a survival benefit, even in patients with very low target expression, the same might be true for T cells.

Look back further: Breakthroughs of 2021

https://leaps.org/6-biotech-breakthroughs-of-2021-that-missed-the-attention-they-deserved/

A participatory research project has evolved in the world's most powerful networked supercomputer to identify drug targets for COVID-19.

With millions of people left feeling helpless as COVID-19 sweeps across the U.S. and the rest of the planet, there is one way in which absolutely anyone can help fight the pandemic -- all you need is a computer and an Internet connection.

"The more donors that participate, the more science we're able to do."

The Folding@home project allows members of the public to contribute a portion of their computing power to a gigantic virtual network which has mushroomed over the past month to become the most powerful supercomputer on the planet.

As of April 6, more than one million people across the globe have donated some of their home computing resources to the project. Combined, this gives Folding@home processing powers that dwarf even NASA and IBM's most powerful devices. To join, all you have to do is go to this website and click 'Download Now' to load the Folding@home software on your computer. This runs in the background, and only adds your unused computing power to the project, so it will not drain resources from tasks you're trying to do.

"It's totally crazy," said Vincent Voelz, associate professor of chemistry at Temple University, Philadelphia, and one of the scientists leading the project. "A month ago, we had around 30,000 to 40,000 participants. And then last week, it rose up 400,000 and now we've hit a million. But the more donors that participate, the more science we're able to do."

Voelz and the other scientists behind Folding@home are using these vast resources to model the ever-changing shapes of the coronavirus's proteins, in the hopes of identifying vulnerabilities or 'pockets' in its structure that can be targeted with new drugs.

One of the reasons it's difficult to find treatments for viruses like COVID-19 and Ebola is because the proteins, the innate building blocks of the viral structure, have notoriously smooth surfaces, making it hard for drugs to bind to them.

But viral proteins don't stay still. They are constantly evolving and changing shape as the atoms within push and pull against each other. Having a supercomputer enables scientists to simulate all these different shapes, revealing potential weaknesses which were not immediately visible. And the more powerful the supercomputer, the faster these simulations can happen.

"Simulating these protein motions also enables us to answer basic questions such as what makes this new coronavirus strain different from previous strains," said Voelz. "Is there something about the dynamics of these proteins that makes it more virulent?"

Finding a genuinely novel drug for COVID-19 is particularly critical.

Once they have identified suitable pockets within the proteins of COVID-19, the Folding@home scientists can then take the many compounds being identified by chemists around the world as potential drugs, and try to predict which ones will stand the best chance of binding to those pockets and inhibiting the virus's ability to invade and take over human cells.

"We have so much bandwidth now with Folding@home that we really think we can make a dent with screening these, and prioritizing which compounds are then going to get experimentally tested," said Voeltz.

The team are particularly hopeful they can succeed, having already used the supercomputer to identify a new vulnerability in the Ebola virus, which could go on to yield a new treatment for the disease.

Finding a genuinely novel drug for COVID-19 is particularly critical. While researchers are also looking at repurposing existing medications, like the antimalarials Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine (which have just been approved by the FDA for emergency use in coronavirus patients), concerns remain about the safety of these treatments. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic recently warned that the use of these drugs could have the side effect of inducing heart problems and run the risk of sudden cardiac arrest.

But with the death toll increasing by the day, speed is of the essence. Voelz explains that the scientific community has been left playing catch-up, because a drug was never actually developed for the original SARS outbreak in the early 2000s. The enormous computational power of the Folding@home project has the potential to allow scientists to quickly answer some of the key questions needed to get a new treatment into the pipeline.

"We don't have a SARS drug for whatever reason," said Voelz. "So the missing ingredient really, is the basic science to reveal possible drug targets and then the pharma can take that information and do the engineering work and optimizing and clinically testing drugs. But we now have a lot of basic science going on in response to this pandemic."

Stefania Sterling with her son Charlie, who was diagnosed at age 3 with autism.

Stefania Sterling was just 21 when she had her son, Charlie. She was young and healthy, with no genetic issues apparent in either her or her husband's family, so she expected Charlie to be typical.

"It is surprising that the prevalence of a significant disorder like autism has risen so consistently over a relatively brief period."

It wasn't until she went to a Mommy and Me music class when he was one, and she saw all the other one-year-olds walking, that she realized how different her son was. He could barely crawl, didn't speak, and made no eye contact. By the time he was three, he was diagnosed as being on the lower functioning end of the autism spectrum.

She isn't sure why it happened – and researchers, too, are still trying to understand the basis of the complex condition. Studies suggest that genes can act together with influences from the environment to affect development in ways that lead to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). But rates of ASD are rising dramatically, making the need to figure out why it's happening all the more urgent.

The Latest News

Indeed, the CDC's latest autism report, released last week, which uses 2016 data, found that the prevalence of ASD in four-year-old children was one in 64 children, or 15.6 affected children per 1,000. That's more than the 14.1 rate they found in 2014, for the 11 states included in the study. New Jersey, as in years past, was the highest, with 25.3 per 1,000, compared to Missouri, which had just 8.8 per 1,000.

The rate for eight-year-olds had risen as well. Researchers found the ASD prevalence nationwide was 18.5 per 1,000, or one in 54, about 10 percent higher than the 16.8 rate found in 2014. New Jersey, again, was the highest, at one in 32 kids, compared to Colorado, which had the lowest rate, at one in 76 kids. For New Jersey, that's a 175 percent rise from the baseline number taken in 2000, when the state had just one in 101 kids.

"It is surprising that the prevalence of a significant disorder like autism has risen so consistently over a relatively brief period," said Walter Zahorodny, an associate professor of pediatrics at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, who was involved in collecting the data.

The study echoed the findings of a surprising 2011 study in South Korea that found 1 in every 38 students had ASD. That was the the first comprehensive study of autism prevalence using a total population sample: A team of investigators from the U.S., South Korea, and Canada looked at 55,000 children ages 7 to 12 living in a community in South Korea and found that 2.64 percent of them had some level of autism.

Searching for Answers

Scientists can't put their finger on why rates are rising. Some say it's better diagnosis. That is, it's not that more people have autism. It's that we're better at detecting it. Others attribute it to changes in the diagnostic criteria. Specifically, the May 2013 update of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 -- the standard classification of mental disorders -- removed the communication deficit from the autism definition, which made more children fall under that category. Cynical observers believe physicians and therapists are handing out the diagnosis more freely to allow access to services available only to children with autism, but that are also effective for other children.

Alycia Halladay, chief science officer for the Autism Science Foundation in New York, said she wishes there were just one answer, but there's not. While she believes the rising ASD numbers are due in part to factors like better diagnosis and a change in the definition, she does not believe that accounts for the entire rise in prevalence. As for the high numbers in New Jersey, she said the state has always had a higher prevalence of autism compared to other states. It is also one of the few states that does a good job at recording cases of autism in its educational records, meaning that children in New Jersey are more likely to be counted compared to kids in other states.

"Not every state is as good as New Jersey," she said. "That accounts for some of the difference compared to elsewhere, but we don't know if it's all of the difference in prevalence, or most of it, or what."

"What we do know is that vaccinations do not cause autism."

There is simply no defined proven reason for these increases, said Scott Badesch, outgoing president and CEO of the Autism Society of America.

"There are suggestions that it is based on better diagnosis, but there are also suggestions that the incidence of autism is in fact increasing due to reasons that have yet been determined," he said, adding, "What we do know is that vaccinations do not cause autism."

Zahorodny, the pediatrics professor, believes something is going on beyond better detection or evolving definitions.

"Changes in awareness and shifts in how children are identified or diagnosed are relevant, but they only take you so far in accounting for an increase of this magnitude," he said. "We don't know what is driving the surge in autism recorded by the ADDM Network and others."

He suggested that the increase in prevalence could be due to non-genetic environmental triggers or risk factors we do not yet know about, citing possibilities including parental age, prematurity, low birth rate, multiplicity, breech presentation, or C-section delivery. It may not be one, but rather several factors combined, he said.

"Increases in ASD prevalence have affected the whole population, so the triggers or risks must be very widely dispersed across all strata," he added.

There are studies that find new risk factors for ASD almost on a daily basis, said Idan Menashe, assistant professor in the Department of Health at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the fastest growing research university in Israel.

"There are plenty of studies that find new genetic variants (and new genes)," he said. In addition, various prenatal and perinatal risk factors are associated with a risk of ASD. He cited a study his university conducted last year on the relationship between C-section births and ASD, which found that exposure to general anesthesia may explain the association.

Whatever the cause, health practitioners are seeing the consequences in real time.

"People say rates are higher because of the changes in the diagnostic criteria," said Dr. Roseann Capanna-Hodge, a psychologist in Ridgefield, CT. "And they say it's easier for children to get identified. I say that's not the truth and that I've been doing this for 30 years, and that even 10 years ago, I did not see the level of autism that I do see today."

Sure, we're better at detecting autism, she added, but the detection improvements have largely occurred at the low- to mid- level part of the spectrum. The higher rates of autism are occurring at the more severe end, in her experience.

A Polarizing Theory

Among the more controversial risk factors scientists are exploring is the role environmental toxins may play in the development of autism. Some scientists, doctors and mental health experts suspect that toxins like heavy metals, pesticides, chemicals, or pollution may interrupt the way genes are expressed or the way endocrine systems function, manifesting in symptoms of autism. But others firmly resist such claims, at least until more evidence comes forth. To date, studies have been mixed and many have been more associative than causative.

"Today, scientists are still trying to figure out whether there are other environmental changes that can explain this rise, but studies of this question didn't provide any conclusive answer," said Menashe, who also serves as the scientific director of the National Autism Research Center at BGU.

"It's not everything that makes Charlie. He's just like any other kid."

That inconclusiveness has not dissuaded some doctors from taking the perspective that toxins do play a role. "Autism rates are rising because there is a mismatch between our genes and our environment," said Julia Getzelman, a pediatrician in San Francisco. "The majority of our evolution didn't include the kinds of toxic hits we are experiencing. The planet has changed drastically in just the last 75 years –- it has become more and more polluted with tens of thousands of unregulated chemicals being used by industry that are having effects on our most vulnerable."

She cites BPA, an industrial chemical that has been used since the 1960s to make certain plastics and resins. A large body of research, she says, has shown its impact on human health and the endocrine system. BPA binds to our own hormone receptors, so it may negatively impact the thyroid and brain. A study in 2015 was the first to identify a link between BPA and some children with autism, but the relationship was associative, not causative. Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration maintains that BPA is safe at the current levels occurring in food, based on its ongoing review of the available scientific evidence.

Michael Mooney, President of St. Louis-based Delta Genesis, a non-profit organization that treats children struggling with neurodevelopmental delays like autism, suspects a strong role for epigenetics, which refers to changes in how genes are expressed as a result of environmental influences, lifestyle behaviors, age, or disease states.

He believes some children are genetically predisposed to the disorder, and some unknown influence or combination of influences pushes them over the edge, triggering epigenetic changes that result in symptoms of autism.

For Stefania Sterling, it doesn't really matter how or why she had an autistic child. That's only one part of Charlie.

"It's not everything that makes Charlie," she said. "He's just like any other kid. He comes with happy moments. He comes with sad moments. Just like my other three kids."