Health breakthroughs of 2022 that should have made bigger news

Nine experts break down the biggest biotech and health breakthroughs that didn't get the attention they deserved in 2022.

As the world has attempted to move on from COVID-19 in 2022, attention has returned to other areas of health and biotech with major regulatory approvals such as the Alzheimer's drug lecanemab – which can slow the destruction of brain cells in the early stages of the disease – being hailed by some as momentous breakthroughs.

This has been a year where psychedelic medicines have gained the attention of mainstream researchers with a groundbreaking clinical trial showing that psilocybin treatment can help relieve some of the symptoms of major depressive disorder. And with messenger RNA (mRNA) technology still very much capturing the imagination, the readouts of cancer vaccine trials have made headlines around the world.

But at the same time there have been vital advances which will likely go on to change medicine, and yet have slipped beneath the radar. I asked nine forward-thinking experts on health and biotech about the most important, but underappreciated, breakthrough of 2022.

Their descriptions, below, were lightly edited by Leaps.org for style and format.

New drug targets for Alzheimer’s disease

Professor Julie Williams, Director, Dementia Research Institute, Cardiff University

Genetics has changed our view of Alzheimer’s disease in the last five to six years. The beta amyloid hypothesis has dominated Alzheimer’s research for a long time, but there are multiple components to this complex disease, of which getting rid of amyloid plaques is one, but it is not the whole story. In April 2022, Nature published a paper which is the culmination of a decade’s worth of work - groups all over the world working together to identify 75 genes associated with risk of developing Alzheimer’s. This provides us with a roadmap for understanding the disease mechanisms.

For example, it is showing that there is something different about the immune systems of people who develop Alzheimer’s disease. There is something different about the way they process lipids in the brain, and very specific processes of how things travel through cells called endocytosis. When it comes to immunity, it indicates that the complement system is affecting whether synapses, which are the connections between neurons, get eliminated or not. In Alzheimer’s this process is more severe, so patients are losing more synapses, and this is correlated with cognition.

The genetics also implicates very specific tissues like microglia, which are the housekeepers in the brain. One of their functions is to clear away beta amyloid, but they also prune and nibble away at parts of the brain that are indicated to be diseased. If you have these risk genes, it seems that you are likely to prune more tissue, which may be part of the cell death and neurodegeneration that we observe in Alzheimer’s patients.

Genetics is telling us that we need to be looking at multiple causes of this complex disease, and we are doing that now. It is showing us that there are a number of different processes which combine to push patients into a disease state which results in the death of connections between nerve cells. These findings around the complement system and other immune-related mechanisms are very interesting as there are already drugs which are available for other diseases which could be repurposed in clinical trials. So it is really a turning point for us in the Alzheimer’s disease field.

Preventing Pandemics with Organ-Tissue Equivalents

Anthony Atala, Director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine

COVID-19 has shown us that we need to be better prepared ahead of future pandemics and have systems in place where we can quickly catalogue a new virus and have an idea of which treatment agents would work best against it.

At Wake Forest Institute, our scientists have developed what we call organ-tissue equivalents. These are miniature tissues and organs, created using the same regenerative medicine technologies which we have been using to create tissues for patients. For example, if we are making a miniature liver, we will recreate this structure using the six different cell types you find in the liver, in the right proportions, and then the right extracellular matrix which holds the structure together. You're trying to replicate all the characteristics of the liver, but just in a miniature format.

We can now put these organ-tissue equivalents in a chip-like device, where we can expose them to different types of viral infections, and start to get a realistic idea of how the human body reacts to these viruses. We can use artificial intelligence and machine learning to map the pathways of the body’s response. This will allow us to catalogue known viruses far more effectively, and begin storing information on them.

Powering Deep Brain Stimulators with Breath

Islam Mosa, Co-Founder and CTO of VoltXon

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices are becoming increasingly common with 150,000 new devices being implanted every year for people with Parkinson’s disease, but also psychiatric conditions such as treatment-resistant depression and obsessive-compulsive disorders. But one of the biggest limitations is the power source – I call DBS devices energy monsters. While cardiac pacemakers use similar technology, their batteries last seven to ten years, but DBS batteries need changing every two to three years. This is because they are generating between 60-180 pulses per second.

Replacing the batteries requires surgery which costs a lot of money, and with every repeat operation comes a risk of infection, plus there is a lot of anxiety on behalf of the patient that the battery is running out.

My colleagues at the University of Connecticut and I, have developed a new way of charging these devices using the person’s own breathing movements, which would mean that the batteries never need to be changed. As the patient breathes in and out, their chest wall presses on a thin electric generator, which converts that movement into static electricity, charging a supercapacitor. This discharges the electricity required to power the DBS device and send the necessary pulses to the brain.

So far it has only been tested in a simulated pig, using a pig lung connected to a pump, but there are plans now to test it in a real animal, and then progress to clinical trials.

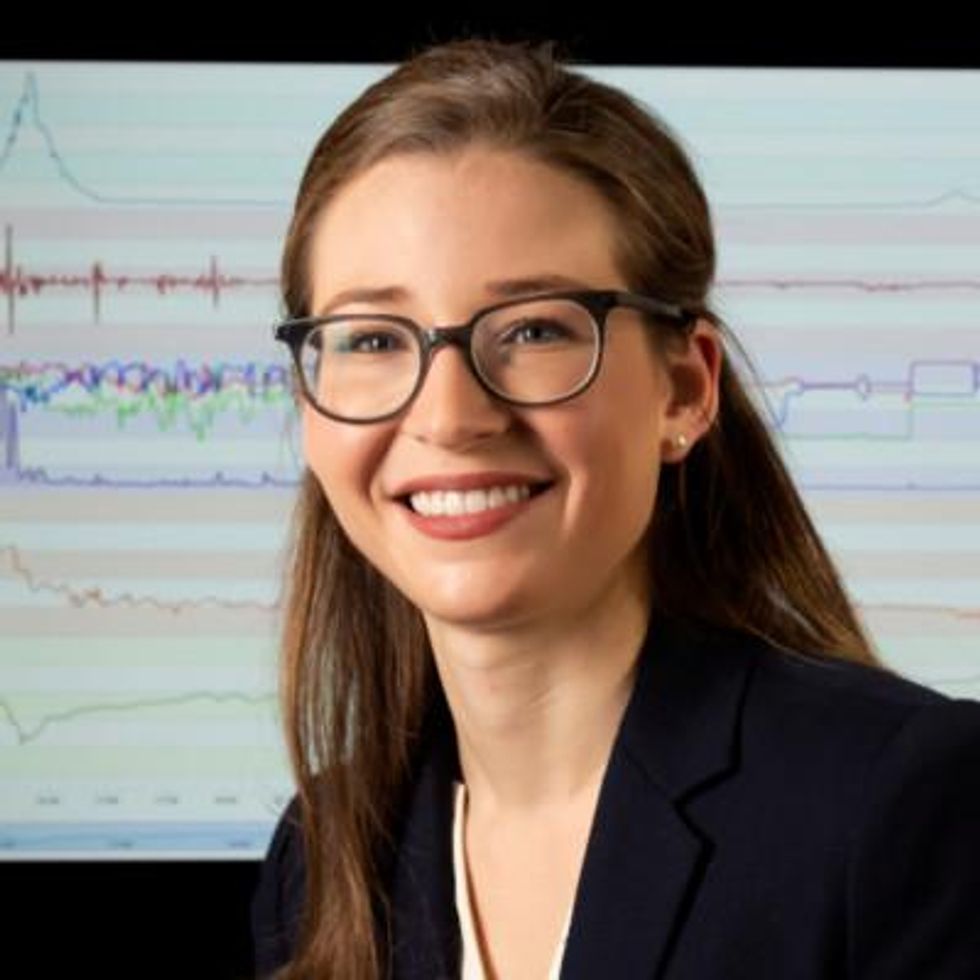

Smartwatches for Disease Detection

Jessilyn Dunn, Assistant Professor in Duke Biomedical Engineering

A group of researchers recently showed that digital biomarkers of infection can reveal when someone is sick, often before they feel sick. The team, which included Duke biomedical engineers, used information from smartwatches to detect Covid-19 cases five to 10 days earlier than diagnostic tests. Smartwatch data included aspects of heart rate, sleep quality and physical activity. Based on this data, we developed an algorithm to decide which people have the most need to take the diagnostic tests. With this approach, the percent of tests that come back positive are about four- to six-times higher, depending on which factors we monitor through the watches.

Our study was one of several showing the value of digital biomarkers, rather than a single blockbuster paper. With so many new ideas and technologies coming out around Covid, it’s hard to be that signal through the noise. More studies are needed, but this line of research is important because, rather than treat everyone as equally likely to have an infectious disease, we can use prior knowledge from smartwatches. With monkeypox, for example, you've got many more people who need to be tested than you have tests available. Information from the smartwatches enables you to improve how you allocate those tests.

Smartwatch data could also be applied to chronic diseases. For viruses, we’re looking for information about anomalies – a big change point in people’s health. For chronic diseases, it’s more like a slow, steady change. Our research lays the groundwork for the signals coming from smartwatches to be useful in a health setting, and now it’s up to us to detect more of these chronic cases. We want to go from the idea that we have this single change point, like a heart attack or stroke, and focus on the part before that, to see if we can detect it.

A Vaccine For RSV

Norbert Pardi, Vaccines Group Lead, Penn Institute for RNA Innovation, University of Pennsylvania

Scientists have long been trying to develop a vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and it looks like Pfizer are closing in on this goal, based on the latest clinical trial data in newborns which they released in November. Pfizer have developed a protein-based vaccine against the F protein of RSV, which they are giving to pregnant women. It turns out that it induces a robust immune response after the administration of a single shot and it seems to be highly protective in newborns. The efficacy was over 80% after 90 days, so it protected very well against severe disease, and even though this dropped a little after six month, it was still pretty high.

I think this has been a very important breakthrough, and very timely at the moment with both COVID-19, influenza and RSV circulating, which just shows the importance of having a vaccine which works well in both the very young and the very old.

The road to an RSV vaccine has also illustrated the importance of teamwork in 21st century vaccine development. You need people with different backgrounds to solve these challenges – microbiologists, immunologists and structural biologists working together to understand how viruses work, and how our immune system induces protective responses against certain viruses. It has been this kind of teamwork which has yielded the findings that targeting the prefusion stabilized form of the F protein in RSV induces much stronger and highly protective immune responses.

Gene therapy shows its potential

Nicole Paulk, Assistant Professor of Gene Therapy at the University of California, San Francisco

The recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Hemgenix, a gene therapy for hemophilia B, is big for a lot of reasons. While hemophilia is absolutely a rare disease, it is astronomically more common than the first two approvals – Luxturna for RPE65-meidated inherited retinal dystrophy and Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy - so many more patients will be treated with this. In terms of numbers of patients, we are now starting to creep up into things that are much more common, which is a huge step in terms of our ability to scale the production of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector for gene therapy.

Hemophilia is also a really special patient population because this has been the darling indication for AAV gene therapy for the last 20 to 30 years. AAV trafficks to the liver so well, it’s really easy for us to target the tissues that we want. If you look at the numbers, there have been more gene therapy scientists working on hemophilia than any other condition. There have just been thousands and thousands of us working on gene therapy indications for the last 20 or 30 years, so to see the first of these approvals make it, feels really special.

I am sure it is even more special for the patients because now they have a choice – do I want to stay on my recombinant factor drug that I need to take every day for the rest of my life, or right now I could get a one-time infusion of this virus and possibly experience curative levels of expression for the rest of my life. And this is just the first one for hemophilia, there’s going to end up being a dozen gene therapies within the next five years, targeted towards different hemophilias.

Every single approval is momentous for the entire field because it gets investors excited, it gets companies and physicians excited, and that helps speed things up. Right now, it's still a challenge to produce enough for double digit patients. But with more interest comes the experiments and trials that allow us to pick up the knowledge to scale things up, so that we can go after bigger diseases like diabetes, congestive heart failure, cancer, all of these much bigger afflictions.

Treating Thickened Hearts

John Spertus, Professor in Metabolic and Vascular Disease Research, UMKC School of Medicine

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease that causes your heart muscle to enlarge, and the walls of your heart chambers thicken and reduce in size. Because of this, they cannot hold as much blood and may stiffen, causing some sufferers to experience progressive shortness of breath, fatigue and ultimately heart failure.

So far we have only had very crude ways of treating it, using beta blockers, calcium channel blockers or other medications which cause the heart to beat less strongly. This works for some patients but a lot of time it does not, which means you have to consider removing part of the wall of the heart with surgery.

Earlier this year, a trial of a drug called mavacamten, became the first study to show positive results in treating HCM. What is remarkable about mavacamten is that it is directed at trying to block the overly vigorous contractile proteins in the heart, so it is a highly targeted, focused way of addressing the key problem in these patients. The study demonstrated a really large improvement in patient quality of life where they were on the drug, and when they went off the drug, the quality of life went away.

Some specialists are now hypothesizing that it may work for other cardiovascular diseases where the heart either beats too strongly or it does not relax well enough, but just having a treatment for HCM is a really big deal. For years we have not been very aggressive in identifying and treating these patients because there have not been great treatments available, so this could lead to a new era.

Regenerating Organs

David Andrijevic, Associate Research Scientist in neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine

As soon as the heartbeat stops, a whole chain of biochemical processes resulting from ischemia – the lack of blood flow, oxygen and nutrients – begins to destroy the body’s cells and organs. My colleagues and I at Yale School of Medicine have been investigating whether we can recover organs after prolonged ischemia, with the main goal of expanding the organ donor pool.

Earlier this year we published a paper in which we showed that we could use technology to restore blood circulation, other cellular functions and even heart activity in pigs, one hour after their deaths. This was done using a perfusion technology to substitute heart, lung and kidney function, and deliver an experimental cell protective fluid to these organs which aimed to stop cell death and aid in the recovery.

One of the aims of this technology is that it can be used in future to lengthen the time window for recovering organs for donation after a person has been declared dead, a logistical hurdle which would allow us to substantially increase the donor pool. We might also be able to use this cell protective fluid in studies to see if it can help people who have suffered from strokes and myocardial infarction. In future, if we managed to achieve an adequate brain recovery – and the brain, out of all the organs, is the most susceptible to ischemia – this might also change some paradigms in resuscitation medicine.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Cancer

Yosi Shamay, Cancer Nanomedicine and Nanoinformatics researcher at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology

For the past four or five years, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) - a cancer drug where you have an antibody conjugated to a toxin - have been used only in patients with specific cancers that display high expression of a target protein, for example HER2-positive breast cancer. But in 2022, there have been clinical trials where ADCs have shown remarkable results in patients with low expression of HER2, which is something we never expected to see.

In July 2022, AstraZeneca published the results of a clinical trial, which showed that an ADC called trastuzumab deruxtecan can offer a very big survival benefit to breast cancer patients with very little expression of HER2, levels so low that they would be borderline undetectable for a pathologist. They got a strong survival signal for patients with very aggressive, metastatic disease.

I think this is very interesting and important because it means that it might pave the way to include more patients in clinical trials looking at ADCs for other cancers, for example lymphoma, colon cancer, lung cancers, even if they have low expression of the protein target. It also holds implications for CAR-T cells - where you genetically engineer a T cell to attack the cancer - because the concept is very similar. If we now know that an ADC can have a survival benefit, even in patients with very low target expression, the same might be true for T cells.

Look back further: Breakthroughs of 2021

https://leaps.org/6-biotech-breakthroughs-of-2021-that-missed-the-attention-they-deserved/

New study: Hotter nights, climate change, cause sleep loss with some affected more than others

According to a new study, sleep is impaired with temperatures over 50 degrees, and temps higher than 77 degrees reduce the chances of getting seven hours.

Data from the National Sleep Foundation finds that the optimal bedroom temperature for sleep is around 65 degrees Fahrenheit. But we may be getting fewer hours of "good sleepin’ weather" as the climate warms, according to a recent paper from researchers at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Published in One Earth, the study finds that heat related to climate change could provide a “pathway” to sleep deprivation. The authors say the effect is “substantially larger” for those in lower-income countries. Hours of sleep decline when nighttime temperature exceeds 50 degrees, and temps higher than 77 reduce the chances of sleeping for seven hours by 3.5 percent. Even small losses associated with rising temperatures contribute significantly to people not getting enough sleep.

We’re affected by high temperatures at night because body temperature becomes more sensitive to the environment when slumbering. “Mechanisms that control for thermal regulation become more disordered during sleep,” explains Clete Kushida, a neurologist, professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and sleep medicine clinician.

The study finds that women and older adults are especially vulnerable. Worldwide, the elderly lost over twice as much sleep per degree of warming compared to younger people. This phenomenon was apparent between the ages of 60 and 70, and it increased beyond age 70. “The mechanism for balancing temperatures appears to be more affected with age,” Kushida adds.

Others disproportionately affected include those who live in regions with more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which accelerate climate change, and people in hotter locales will lose more sleep per degree of warming, according to the study, with suboptimal temperatures potentially eroding 50 to 58 hours of sleep per person per year. One might think that those in warmer countries can adapt to the heat, but the researchers found no evidence for such adjustments. “We actually found those living in the warmest climate regions were impacted over twice as much as those in the coldest climate regions,” says the study's lead author, Kelton Minor, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Copenhagen’s Center for Social Data Science.

Short sleep can reduce cognitive performance and productivity, increase absenteeism from work or school, and lead to a host of other physical and psychosocial problems. These issues include a compromised immune system, hypertension, depression, anger and suicide, say the study’s authors. According to a fact sheet by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a third of U.S. adults already report sleeping fewer hours than the recommended amount, even though sufficient sleep “is not a luxury—it is something people need for good health.”

Equitable policy and planning are needed to ensure equal access to cooling technologies in a warming world.

Beyond global health, a sleep-deprived world will impact the economy as the climate warms. “Less productivity at work, associated with sleep loss or deprivation, would result in more sick days on a global scale, not just in individual countries,” Kushida says.

Unlike previous research that measured sleep patterns with self-reported surveys and controlled lab experiments, the study in One Earth offers a global analysis that relies on sleep-tracking wristbands that link more than seven million sleep records of 47,628 adults across 68 countries to local and daily meteorological data, offering new insight into the environmental impact on human sleep. Controlling for individual, seasonal and time-varying confounds, researchers found the main way that higher temperatures shorten slumber is by delaying sleep onset.

Heat effects on sleep were seen in industrialized countries including those with access to air conditioning, notes the study. Air conditioning may buffer high indoor temperatures, but they also increase GHG emissions and ambient heat displacement, thereby exacerbating the unequal burdens of global and local warming. Continued urbanization is expected to contribute to these problems.

Previous sleep studies have found an inverse U-shaped response to temperature in highly controlled settings, with subjects sleeping worse when room temperatures were either too cold or too warm. However, “people appear far better at adapting to colder outside temperatures than hotter conditions,” says Minor.

Although there are ways of countering the heat effect, some populations have more access to them. “Air conditioning can help with the effect of higher temperature, but not all individuals can afford air conditioners,” says Kushida. He points out that this could drive even greater inequity between higher- and lower-income countries.

Equitable policy and planning are needed to ensure equal access to cooling technologies in a warming world. “Clean and renewable energy systems and interventions will be needed to mitigate and adapt to ongoing climate warming,” Minor says. Future research should investigate “policy, planning and design innovation,” which could reduce the impact of sweltering temperatures on a good night’s sleep for the good of individuals, society and our planet, asserts the study.

Unabated and on its current trajectory, by 2099 suboptimal temperatures could shave 50 to 58 hours of sleep per person per year, predict the study authors. “Down the road, as technology develops, there might be ways of enabling people to adapt on a large scale to these higher temperatures,” says Kushida. “Right now, it’s not there.”

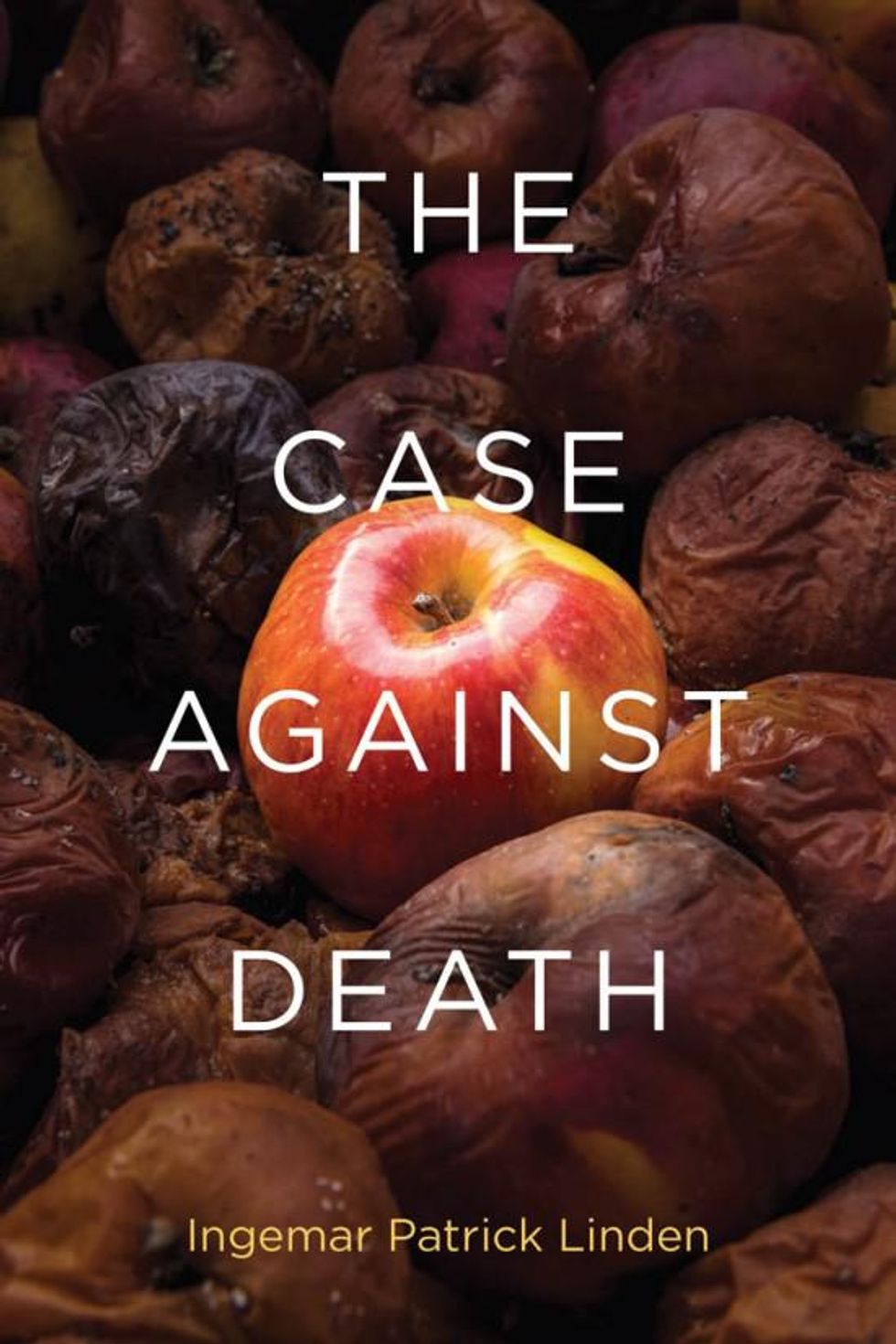

Why we need to get serious about ending aging

With the population of older people projected to grow dramatically, and the cost of healthcare with it, the future welfare of the country may depend on solving aging, writes philosopher Ingemar Patrick Linden.

It is widely acknowledged that even a small advance in anti-aging science could yield benefits in terms of healthy years that the traditional paradigm of targeting specific diseases is not likely to produce. A more youthful population would also be less vulnerable to epidemics. Approximately 93 percent of all COVID-19 deaths reported in the U.S. occurred among those aged 50 or older. The potential economic benefits would be tremendous. A more youthful population would consume less medical resources and be able to work longer. A recent study published in Nature estimates that a slowdown in aging that increases life expectancy by one year would save $38 trillion per year for the U.S. alone.

A societal effort to understand, slow down, arrest or even reverse aging of at least the size of our response to COVID-19 would therefore be a rational commitment. In fact, given that America’s older population is projected to grow dramatically, and the cost of healthcare with it, it is not an overstatement to say that the future welfare of the country may depend on solving aging.

This year, the kingdom of Saudi Arabia has announced that it will spend up to 1 billion dollars per year on science with the potential to slow down the aging process. We have also seen important investments from billionaires like Google co-founder Larry Page, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, business magnate Larry Ellison, and PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel.

The U.S. government, however, is lagging: The National Institutes of Health spent less than one percent of its $43 billion budget for the fiscal year of 2021 on the National Institute on Aging’s Division of Aging Biology. When you visit the division’s webpage you find that their mission statement carefully omits any mention of the possibility of slowing down the aging process.

There is a lack of political will and leadership on the issue, and the idea that we should seek to do something about aging is generally met with a great deal of suspicion and trepidation. In a large representative study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2013, only 38% of the respondents said that they would want a treatment that could slow the aging process and allow them to live at least 120 years. Apparently, most people prefer, or at least do not mind, to age and die within a natural lifespan. This result has been confirmed by smaller studies and it is, I think, surprising. Are we not supposed to live in a youth-culture? Are people not supposed to want to stay young and alive forever? Is self-preservation not the strong drive we have always assumed it to be?

We are inundated and saturated with an ideology of death-acceptance.

In my book, The Case against Death, I suggest that we have been culturally conditioned to think that it is virtuous to accept aging and death. We are taught to believe that although aging and death seem gruesome, they are what is best for us, all things considered. This is what we are supposed to think, and the majority accept it. I call this the Wise View because death acceptance has been the dominant view of philosophers since the beginning. Socrates compared our earthly life to an illness and a prison and described death as a healer and a liberator. The Buddha taught that life is suffering and that the way to escape suffering is to end the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Stoic philosophers from Zeno to Marcus Aurelius believed that everything that happens in accordance with nature is good, and that therefore we should not only accept death but welcome it as an aspect of a perfect totality.

Epicureans agreed with these rival schools and famously argued that death cannot harm us because where we are, death is not, and where death is we are not. We cannot be harmed if we are not, so death is harmless. The simple view that death actually can harm us greatly is one of the least philosophical views one can hold.

In The Case Against Death, philosopher Ingemar Patrick Linden argues that we frown on using science to prolong healthy life only because we're culturally conditioned to think that way.

Many of the stories we tell promote the Wise View. One of the earliest known pieces of literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh, follows Gilgamesh on a quest for eternal life ending with the wisdom that death is the destiny of man. Today we learn about the tedium of immortality from the children’s book Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt, and we are warned about the vice of wanting to resist death in other books and films such as J.K Rowling’s Harry Potter, where Voldemort must kill Harry as a step towards his own immortality; C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia where the White Witch has gained immortal youth and madness in equal measures; J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy where the ring extends the wearer’s life but can also destroy them, as exemplified by the creep Gollum; and Doctor Strange where life extension is the one magical power that is taboo. In Star Wars, Yoda, a stereotype of the sage, teaches us the wisdom handed down by philosophers and prophets: “Death is a natural part of life. Rejoice for those around you who transform into the Force. Mourn them do not. Miss them do not.”

We are inundated and saturated with an ideology of death-acceptance. Can the dear reader name one single story where the hero is pursuing anti-aging, longevity or immortality and the villain tries to stop her?

The Wise View resonates with us partly because we think that there is nothing we can do about aging and death, so we do not want to wish for what we cannot have. Youth and immortality are sour grapes to us. Believing that death is, all things considered, not such a bad thing, protects us from experiencing our aging and approaching death as a gruesome tragedy. This need to escape the thought that we are heading towards a personal catastrophe explains why many are so quick to accept arguments against radical life extension, despite their often glaring weaknesses.

One of the most common objections to radical life extension is that aging and death are natural. The problem with this argument is that many things that are natural are very bad, such as cancer, and other things that are not natural are very good, such as a cure for cancer. Why are we so sure that cancer is bad? Because we assume that it is bad to die. Indeed, nothing is more natural than wanting to live. We seem to need philosophers and story tellers to talk us out of it and, in the words of a distinguished bioethicist, “instruct and somewhat moderate our lust for life.”

Another standard objection is that we need a deadline, and that without death we could postpone every action forever. “Death brings urgency and seriousness to life,” say proponents of this view, but there are several problems with this argument. Even if our lives were endless, there would still be many things we would have to do at a certain time, and that could not be redone, for example, saving our planet from being destroyed, or becoming the first person on Venus. And if we prefer pleasant endless lives over unpleasant endless ones, we will have to exercise, eat right, keep our word, develop our talents, show up for time at work, pay our taxes by the due date, remember birthdays, and so on.

The Wise View provides us with a feel-good bromide for the anxiety created by the foreknowledge of our decay and death by telling us that these are not evils, but blessings in disguise. Once perhaps an innocuous delusion, today the view stands in the way of a necessary societal commitment to research that can prolong our healthy life.

Besides, even if we succeeded in ending aging, we would still die from other causes. Given the rate of accidental deaths we would be fortunate to live to age 2000 all things equal. So even if, contrary to what I have argued, we do need a deadline, we can still argue that the natural lifespan that we now labor under is inhuman and that it forces each human to limit her ambitions and to become only a fragment of all that she that could have been. Our tight time constraint imposes tragic choices and inflated opportunity costs. Death does not make life matter; it makes time matter.

The perhaps most awful argument against radical life extension is grounded in a pessimism that holds life in such little regard that it says that best of all is never to have born. This view was expressed by Ecclesiastes in the Hebrew Bible, by Sophocles and several other ancient Greeks, by the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, and recently by, among others, the South African philosopher David Benatar who argues that it is wrong to bring children into the world and that we should euthanize all sentient life. Pessimism, one suspects, largely appeals to some for reasons having to do with personal temperament, but insofar as it is built on factual beliefs, they can be addressed by providing a less negatively biased understanding of the world, by pointing out that curing aging would decrease the badness that they are so hypersensitive to, and by reminding them that if life really becomes unbearable, they are free to quit at any time. Other means of persuasion could include recommending sleep, exercise and taking long brisk walks in nature.

The Wise View provides us with a feel-good bromide for the anxiety created by the foreknowledge of our decay and death by telling us that these are not evils, but blessings in disguise. Once perhaps an innocuous delusion, today the view stands in the way of a necessary societal commitment to research that can prolong our healthy life. We need abandon it and openly admit that aging is a scourge that deserves to be fought with the combined energies equaling those expended on fighting COVID-19, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, stroke and all the other illnesses for which aging is the greatest risk factor. The fight to end aging transcends ordinary political boundaries and is therefore the kind of grand unifying enterprise that could re-energize a society suffering from divisiveness and the sense of a lack of a common purpose. It is hard to imagine a more worthwhile cause.