If New Metal Legs Let You Run 20 Miles/Hour, Would You Amputate Your Own?

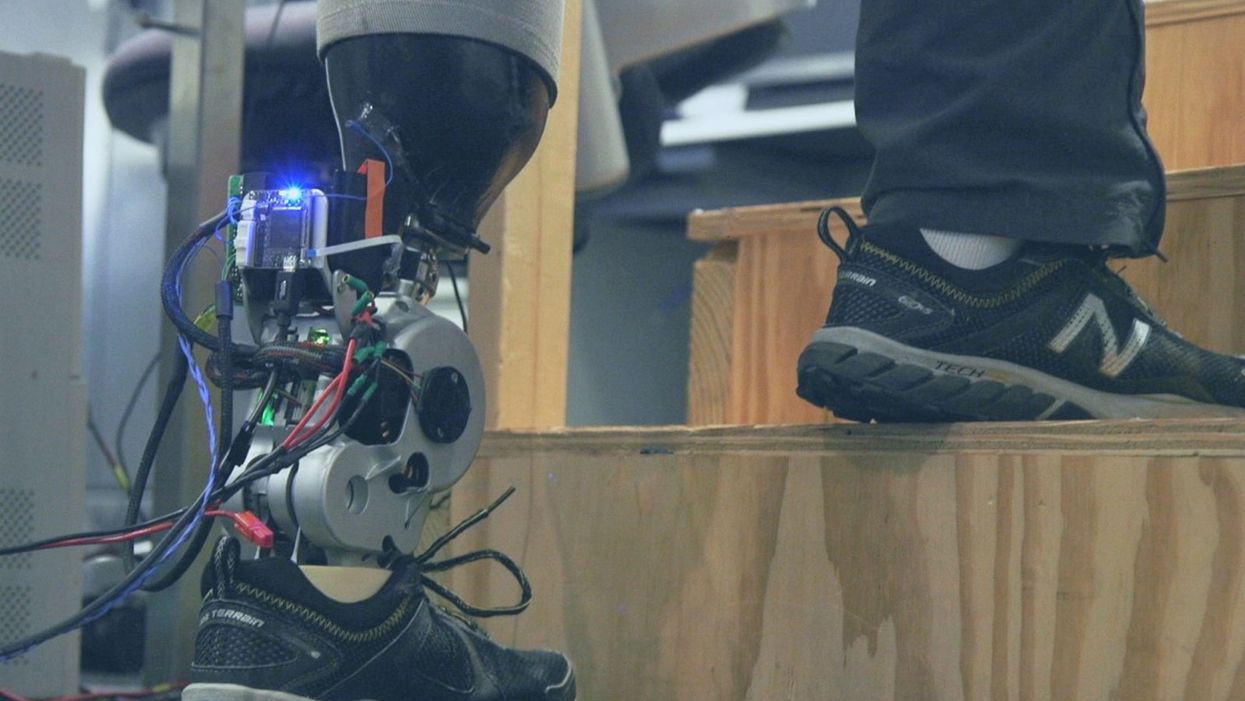

A patient with below-knee AMI amputation walks up the stairs.

"Here's a question for you," I say to our dinner guests, dodging a knowing glance from my wife. "Imagine a future in which you could surgically replace your legs with robotic substitutes that had all the functionality and sensation of their biological counterparts. Let's say these new legs would allow you to run all day at 20 miles per hour without getting tired. Would you have the surgery?"

Why are we so married to the arbitrary distinction between rehabilitating and augmenting?

Like most people I pose this question to, our guests respond with some variation on the theme of "no way"; the idea of undergoing a surgical procedure with the sole purpose of augmenting performance beyond traditional human limits borders on the unthinkable.

"Would your answer change if you had arthritis in your knees?" This is where things get interesting. People think differently about intervention when injury or illness is involved. The idea of a major surgery becomes more tractable to us in the setting of rehabilitation.

Consider the simplistic example of human walking speed. The average human walks at a baseline three miles per hour. If someone is only able to walk at one mile per hour, we do everything we can to increase their walking ability. However, to take a person who is already able to walk at three miles per hour and surgically alter their body so that they can walk twice as fast seems, to us, unreasonable.

What fascinates me about this is that the three-mile-per-hour baseline is set by arbitrary limitations of the healthy human body. If we ignore this reference point altogether, and consider that each case simply offers an improvement in walking ability, the line between augmentation and rehabilitation all but disappears. Why, then, are we so married to this arbitrary distinction between rehabilitating and augmenting? What makes us hold so tightly to baseline human function?

Where We Stand Now

As the functionality of advanced prosthetic devices continues to increase at an astounding rate, questions like these are becoming more relevant. Experimental prostheses, intended for the rehabilitation of people with amputation, are now able to replicate the motions of biological limbs with high fidelity. Neural interfacing technologies enable a person with amputation to control these devices with their brain and nervous system. Before long, synthetic body parts will outperform biological ones.

Our approach allows people to not only control a prosthesis with their brain, but also to feel its movements as if it were their own limb.

Against this backdrop, my colleagues and I developed a methodology to improve the connection between the biological body and a synthetic limb. Our approach, known as the agonist-antagonist myoneural interface ("AMI" for short), enables us to reflect joint movement sensations from a prosthetic limb onto the human nervous system. In other words, the AMI allows people to not only control a prosthesis with their brain, but also to feel its movements as if it were their own limb. The AMI involves a reimagining of the amputation surgery, so that the resultant residual limb is better suited to interact with a neurally-controlled prosthesis. In addition to increasing functionality, the AMI was designed with the primary goal of enabling adoption of a prosthetic limb as part of a patient's physical identity (known as "embodiment").

Early results have been remarkable. Patients with below-knee AMI amputation are better able to control an experimental prosthetic leg, compared to people who had their legs amputated in the traditional way. In addition, the AMI patients show increased evidence of embodiment. They identify with the device, and describe feeling as though it is part of them, part of self.

Where We're Going

True embodiment of robotic devices has the potential to fundamentally alter humankind's relationship with the built world. Throughout history, humans have excelled as tool builders. We innovate in ways that allow us to design and augment the world around us. However, tools for augmentation are typically external to our body identity; there is a clean line drawn between smart phone and self. As we advance our ability to integrate synthetic systems with physical identity, humanity will have the capacity to sculpt that very identity, rather than just the world in which it exists.

For this potential to be realized, we will need to let go of our reservations about surgery for augmentation. In reality, this shift has already begun. Consider the approximately 17.5 million surgical and minimally invasive cosmetic procedures performed in the United States in 2017 alone. Many of these represent patients with no demonstrated medical need, who have opted to undergo a surgical procedure for the sole purpose of synthetically enhancing their body. The ethical basis for such a procedure is built on the individual perception that the benefits of that procedure outweigh its costs.

At present, it seems absurd that amputation would ever reach this point. However, as robotic technology improves and becomes more integrated with self, the balance of cost and benefit will shift, lending a new perspective on what now seems like an unfathomable decision to electively amputate a healthy limb. When this barrier is crossed, we will collide head-on with the question of whether it is acceptable for a person to "upgrade" such an essential part of their body.

At a societal level, the potential benefits of physical augmentation are far-reaching. The world of robotic limb augmentation will be a world of experienced surgeons whose hands are perfectly steady, firefighters whose legs allow them to kick through walls, and athletes who never again have to worry about injury. It will be a world in which a teenage boy and his grandmother embark together on a four-hour sprint through the woods, for the sheer joy of it. It will be a world in which the human experience is fundamentally enriched, because our bodies, which play such a defining role in that experience, are truly malleable.

This is not to say that such societal benefits stand without potential costs. One justifiable concern is the misuse of augmentative technologies. We are all quite familiar with the proverbial supervillain whose nervous system has been fused to that of an all-powerful robot.

The world of robotic limb augmentation will be a world of experienced surgeons whose hands are perfectly steady.

In reality, misuse is likely to be both subtler and more insidious than this. As with all new technology, careful legislation will be necessary to work against those who would hijack physical augmentations for violent or oppressive purposes. It will also be important to ensure broad access to these technologies, to protect against further socioeconomic stratification. This particular issue is helped by the tendency of the cost of a technology to scale inversely with market size. It is my hope that when robotic augmentations are as ubiquitous as cell phones, the technology will serve to equalize, rather than to stratify.

In our future bodies, when we as a society decide that the benefits of augmentation outweigh the costs, it will no longer matter whether the base materials that make us up are biological or synthetic. When our AMI patients are connected to their experimental prosthesis, it is irrelevant to them that the leg is made of metal and carbon fiber; to them, it is simply their leg. After our first patient wore the experimental prosthesis for the first time, he sent me an email that provides a look at the immense possibility the future holds:

What transpired is still slowly sinking in. I keep trying to describe the sensation to people. Then this morning my daughter asked me if I felt like a cyborg. The answer was, "No, I felt like I had a foot."

The upcoming vaccine is changing the way we look at treating one of the country’s deadliest cancers.

Last week, researchers at the University of Oxford announced that they have received funding to create a brand new way of preventing ovarian cancer: A vaccine. The vaccine, known as OvarianVax, will teach the immune system to recognize and destroy mutated cells—one of the earliest indicators of ovarian cancer.

Understanding Ovarian Cancer

Despite advancements in medical research and treatment protocols over the last few decades, ovarian cancer still poses a significant threat to women’s health. In the United States alone, more than 12,0000 women die of ovarian cancer each year, and only about half of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer survive five or more years past diagnosis. Unlike cervical cancer, there is no routine screening for ovarian cancer, so it often goes undetected until it has reached advanced stages. Additionally, the primary symptoms of ovarian cancer—frequent urination, bloating, loss of appetite, and abdominal pain—can often be mistaken for other non-cancerous conditions, delaying treatment.

An American woman has roughly a one percent chance of developing ovarian cancer throughout her lifetime. However, these odds increase significantly if she has inherited mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Women who carry these mutations face a 46% lifetime risk for ovarian and breast cancers.

An Unlikely Solution

To address this escalating health concern, the organization Cancer Research UK has invested £600,000 over the next three years in research aimed at creating a vaccine, which would destroy cancerous cells before they have a chance to develop any further.

Researchers at the University of Oxford are at the forefront of this initiative. With funding from Cancer Research UK, scientists will use tissue samples from the ovaries and fallopian tubes of patients currently battling ovarian cancer. Using these samples, University of Oxford scientists will create a vaccine to recognize certain proteins on the surface of ovarian cancer cells known as tumor-associated antigens. The vaccine will then train that person’s immune system to recognize the cancer markers and destroy them.

The next step

Once developed, the vaccine will first be tested in patients with the disease, to see if their ovarian tumors will shrink or disappear. Then, the vaccine will be tested in women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations as well as women in the general population without genetic mutations, to see whether the vaccine can prevent the cancer altogether.

While the vaccine still has “a long way to go,” according to Professor Ahmed Ahmed, Director of Oxford University’s ovarian cancer cell laboratory, he is “optimistic” about the results.

“We need better strategies to prevent ovarian cancer,” said Ahmed in a press release from the University of Oxford. “Currently, women with BRCA1/2 mutations are offered surgery which prevents cancer but robs them of the chance to have children afterward.

Teaching the immune system to recognize the very early signs of cancer is a tough challenge. But we now have highly sophisticated tools which give us real insights into how the immune system recognizes ovarian cancer. OvarianVax could offer the solution.”

How sharing, hearing, and remembering positive stories can help shape our brains for the better

Across cultures and through millennia, human beings have always told stories. Whether it’s a group of boy scouts around a campfire sharing ghost stories or the paleolithic Cro-Magnons etching pictures of bison on cave walls, researchers believe that storytelling has been universal to human beings since the development of language.

But storytelling was more than just a way for our ancestors to pass the time. Researchers believe that storytelling served an important evolutionary purpose, helping humans learn empathy, share important information (such as where predators were or what berries were safe to eat), as well as strengthen social bonds. Quite literally, storytelling has made it possible for the human race to survive.

Today, neuroscientists are discovering that storytelling is just as important now as it was millions of years ago. Particularly in sharing positive stories, humans can more easily form relational bonds, develop a more flexible perspective, and actually grow new brain circuitry that helps us survive. Here’s how.

How sharing stories positively impacts the brain

When human beings share stories, it increases the levels of certain neurochemicals in the brain, neuroscientists have found. In a 2021 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Swedish researchers found that simply hearing a story could make hospitalized children feel better, compared to other hospitalized children who played a riddle game for the same amount of time. In their research, children in the intensive care unit who heard stories for just 30 minutes had higher levels of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes positive feelings and is linked to relaxation, trust, social connectedness, and overall psychological stability. Furthermore, the same children showed lower levels of cortisol, a hormone associated with stress. Afterward, the group of children who heard stories tended to describe their hospital experiences more positively, and even reported lower levels of pain.

Annie Brewster, MD, knows the positive effect of storytelling from personal experience. An assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and the author of The Healing Power of Storytelling: Using Personal Narrative to Navigate Illness, Trauma, and Loss, Brewster started sharing her personal experience with chronic illness after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2001. In doing so, Brewster says it has enabled her to accept her diagnosis and integrate it into her identity. Brewster believes so much in the power of hearing and sharing stories that in 2013 she founded Health Story Collaborative, a forum for others to share their mental and physical health challenges.“I wanted to hear stories of people who had found ways to move forward in positive ways, in spite of health challenges,” Brewster said. In doing so, Brewster believes people with chronic conditions can “move closer to self-acceptance and self-love.”

While hearing and sharing positive stories has been shown to increase oxytocin and other “feel good” chemicals, simply remembering a positive story has an effect on our brains as well. Mark Hoelterhoff, PhD, a lecturer in clinical psychology at the University of Edinburgh, recalling and “savoring” a positive story, thought, or feedback “begins to create new brain circuitry—a new neural network that’s geared toward looking for the positive,” he says. Over time, other research shows, savoring positive stories or thoughts can literally change the shape of your brain, hard-wiring someone to see things in a more positive light.How stories can change your behavior

In 2009, Paul Zak, PhD, a neuroscientist and professor at Claremont Graduate University, set out to measure how storytelling can actually change human behavior for the better. In his study, Zak wanted to measure the behavioral effects of oxytocin, and did this by showing test subjects two short video clips designed to elicit an emotional response.

In the first video they showed the study participants, a father spoke to the camera about his two-year-old son, Ben, who had been diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. The father told the audience that he struggled to connect with and enjoy Ben, as Ben had only a few months left to live. In the end, the father finds the strength to stay emotionally connected to his son until he dies.

The second video clip, however, was much less emotional. In that clip, the same father and son are shown spending the day at the zoo. Ben is only suggested to have cancer (he is bald from chemotherapy and referred to as a ‘miracle’, but the cancer isn’t mentioned directly). The second story lacked the dramatic narrative arc of the first video.

Zak’s team took blood before and after the participants watched one of the two videos and found that the first story increased the viewers’ cortisol and oxytocin, suggesting that they felt distress over the boy’s diagnosis and empathy toward the boy and his father. The second narrative, however, didn’t increase oxytocin or cortisol at all.

But Zak took the experiment a step further. After the movie clips, his team gave the study participants a chance to share money with a stranger in the lab. The participants who had an increase in cortisol and oxytocin were more likely to donate money generously. The participants who had increased cortisol and oxytocin were also more likely to donate money to a charity that works with children who are ill. Zak also found that the amount of oxytocin that was released was correlated with how much money people felt comfortable giving—in other words, the more oxytocin that was released, the more generous they felt, and the more money they donated.

How storytelling strengthens our bond with others

Sharing, hearing, and remembering stories can be a powerful tool for social change–not only in the way it changes our brain and our behavior, but also because it can positively affect our relationships with other people

Emotional stimulation from telling stories, writes Zak, is the foundation for empathy, and empathy strengthens our relationships with other people. “By knowing someone’s story—where they come from, what they do, and who you might know in common—relationships with strangers are formed.”

But why are these relationships important for humanity? Because human beings can use storytelling to build empathy and form relationships, it enables them to “engage in the kinds of large-scale cooperation that builds massive bridges and sends humans into space,” says Zak.

Storytelling, Zak found, and the oxytocin release that follows, also makes people more sensitive to social cues. This sensitivity not only motivates us to form relationships, but also to engage with other people and offer help, particularly if the other person seems to need help.

But as Zak found in his experiments, the type of storytelling matters when it comes to affecting relationships. Where Zak found that storytelling with a dramatic arc helps release oxytocin and cortisol, enabling people to feel more empathic and generous, other researchers have found that sharing happy stories allows for greater closeness between individuals and speakers. A group of Chinese researchers found that, compared to emotionally-neutral stories, happy stories were more “emotionally contagious.” Test subjects who heard happy stories had greater activation in certain areas of their brains, experienced more significant, positive changes in their mood, and felt a greater sense of closeness between themselves and the speaker.

“This finding suggests that when individuals are happy, they become less self-focused and then feel more intimate with others,” the authors of the study wrote. “Therefore, sharing happiness could strengthen interpersonal bonding.” The researchers went on to say that this could lead to developing better social networks, receiving more social support, and leading more successful social lives.

Since the start of the COVID pandemic, social isolation, loneliness, and resulting mental health issues have only gotten worse. In light of this, it’s safe to say that hearing, sharing, and remembering stories isn’t just something we can do for entertainment. Storytelling has always been central to the human experience, and now more than ever it’s become something crucial for our survival.

Want to know how you can reap the benefits of hearing happy stories? Keep an eye out for Upworthy’s first book, GOOD PEOPLE: Stories from the Best of Humanity, published by National Geographic/Disney, available on September 3, 2024. GOOD PEOPLE is a much-needed trove of life-affirming stories told straight from the heart. Handpicked from Upworthy’s community, these 101 stories speak to the breadth, depth, and beauty of the human experience, reminding us we have a lot more in common than we realize.