How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

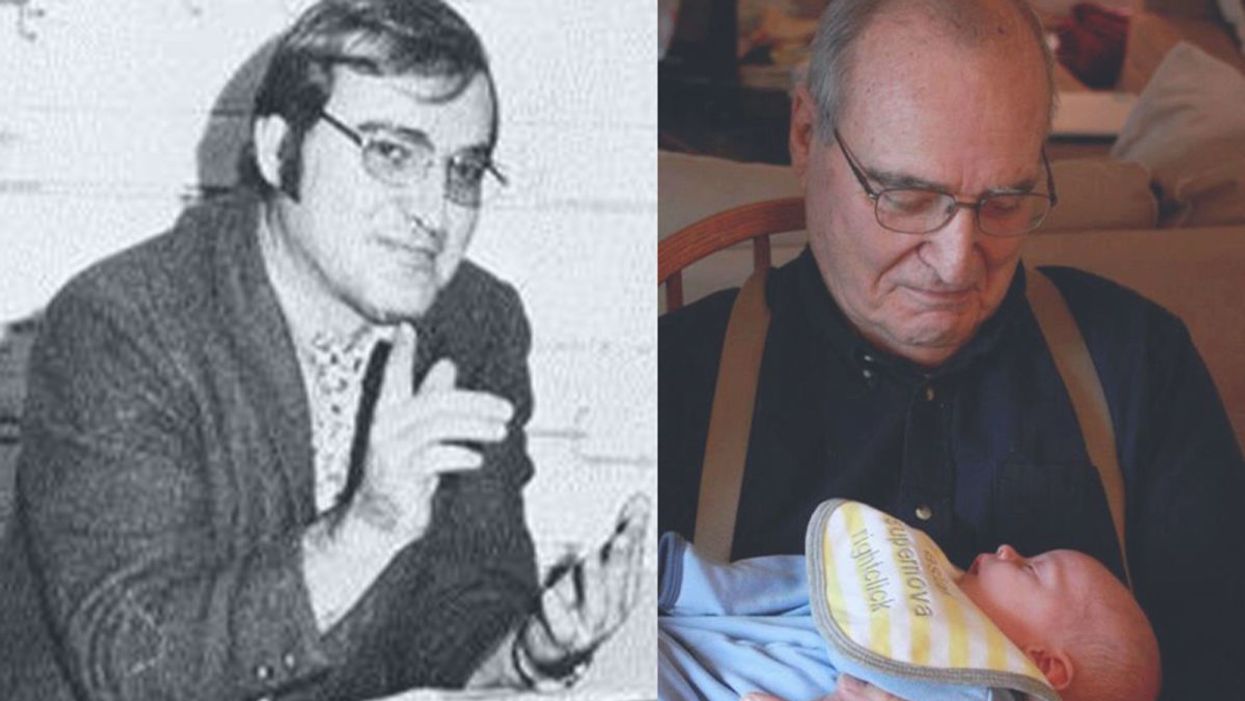

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

Making Sense of Science features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

Episode 1: "COVID-19 Vaccines and Our Progress Toward Normalcy"

Bioethicist Arthur Caplan of NYU shares his thoughts on when we will build herd immunity, how enthusiastic to be about the J&J vaccine, predictions for vaccine mandates in the coming months, what should happen with kids and schools, whether you can hug your grandparents after they get vaccinated, and more.

Transcript:

KIRA: Hi, and welcome to our new podcast 'Making Sense of Science', the show that features interviews with leading experts in health and science about the latest developments and the big ethical questions. I'm your host Kira Peikoff, the editor of leaps.org. And today, we're going to talk about the Covid-19 vaccines. I'm honored that my first guest is Dr. Art Caplan of NYU, one of the world's leading bio-ethicists. Art, thanks so much for joining us today.

DR. CAPLAN: Thank you so much for having me.

KIRA: So the big topic right now is the new J&J vaccine, which is likely to be given to millions of Americans in the coming weeks. It only requires one-shot, it can be stored in refrigerators for several months. It has fewer side-effects and most importantly, it is extremely effective at the big things, preventing hospitalizations and deaths. Though not as effective as Pfizer and Moderna in preventing moderate cases, especially potentially in older adults with underlying conditions. So Art, what's your take overall, on how enthusiastic Americans should be about this vaccine?

DR. CAPLAN: I'm usually enthusiastic. The more weapons, the better. This vaccine, while maybe, slightly less efficacious than the Moderna and the Pfizer ones, is easier to make, is easier to ship. It's one-shot. You know, here there's already been problems of getting people to come back in for their second shots. I would say 5... 7% of people don't show up even though you remind them and you nag them, they don't come back. So a one-shot option is great. A one-shot option that's easy to, if you will, brew up in your rural pharmacy without having to have special instructions is great. And I think it's gonna really facilitate herd-immunity, meaning, we'll see millions and millions and millions of doses of the Janssen vaccine out there as an option, I'm gonna say, summer.

KIRA: Great. And to be fair, it's worth mentioning that the J&J vaccine was tested in clinical trials after variants began to circulate, and it's only one-shot instead of two, like the other vaccines, and it gets more effective over time. So is it really fair to directly compare its efficacy to the mRNA vaccines?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, you know, people are gonna do that. And one issue that'll come up ethically is people are gonna say, "Can I choose my vaccine? I want the most efficacious one. I want the name brand that I trust. I don't want the new platform. I like Janssen's 'cause it's an older, more established way to make vaccines or whatever." Who knows what cuckoo-cockamamie reasons they might have. To me, you take what you can get, it'll be great. It's way above what we normally would expect, those 95% success rates are off the charts. Getting something that's 70% effective, it's perfectly wonderful. I wish we had flu shots that were 70% effective.

And the other thing to keep in mind is we're gonna see more mutations, we're gonna see more strains. That's just a reality of viruses. So they'll mutate, more strains will appear, we can't just say, "Oh my goodness. There's a South-African one or the California one or the UK one. We better... I don't know, do something different." We're just gonna have to basically resign ourselves, I think, to boosters. So right now, take the vaccine. I'm almost tempted to say, "Shut up and take the vaccine. Don't worry about choosing."

Just get what you can get. If you live in a rural community and all they have is Janssen, take it. If you're in another country and all they ship to you is Janssen, take it. And then we'll worry about the next round of virus mutations, if you will, when we get to the boosters. I'm more concerned that these things aren't gonna last more than a year or two than I am that they're not gonna pick up every mutation.

KIRA: So on that note, shipping to rural places or low-income countries that lack the ultra-cold freezers that you need for the super effective mRNA vaccines, the Janssen vaccine seems like a really great option, but are we going to encounter a potential conflict of people saying, "Well, there's "poor or rich vaccines," and one is slightly less effective than the other." And so are we gonna disenfranchise people and undermine their actual willingness to take the vaccine?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, it's interesting. I think the first problem is gonna be, "I have vaccine and I don't have any vaccine," between rich and poor countries. Look, the poor countries are screaming to get vaccine supply sent to them. I think, for example, Ghana received recently 600 million doses of AstraZeneca vaccine. It was freed up by South Africa, which decided they didn't wanna use it 'cause they thought there was "a better vaccine" coming. So even among the poorer nations or the developing nations, some vaccines are getting typed as the not-as-good or the less-desirable... We've already started to see it.

But for the most part, the rich countries are gonna try and vaccinate to herd immunity, you can argue about the ethics of whether that's right, before they start sharing. And I think we'll have haves and have-nots, herd immunity produced in the rich countries, Japan, North America, Europe, by the end of the year anyway. And still some countries floundering around saying, "I didn't get anything," and what are you gonna do?

KIRA: And I know you said to people, which is a very memorable quote, "just shut up and take the vaccine, whatever you can get, whatever is available to you now, do it." But inevitably, as you mentioned, some people are going to say, "Well, I just wanna wait to get the best one possible." When will people have a choice in vaccines, do you think?

DR. CAPLAN: I don't think you'll see that till next year. I think we're gonna see distribution according to where the supply chains are that the vaccine manufacturers use. So if I use McKesson and they ship to the Northeast, and that's where my vaccine goes, that's what's available there. If I'm contracted to Walmart and they buy Janssen, that's what you're gonna see at the big box store. I don't think you're really gonna get too much in the way of choice until next year, when then they're gonna say they ship three different kinds of vaccine, and I can offer you one dose or two dose... One of them lasts a year, one of them lasts 18 months. I don't think we're gonna have the informed choice until next year.

KIRA: Okay. And right now the steep demand is outstripping the supply, and there's been a lot of pressure put on the vaccine makers to ramp up as quickly as possible. Of course, they say that they're doing that and the government is pressuring them to do that, but when do you think we'll cross over to the point where vaccine hesitancy is a bigger issue than vaccine demand?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. So this is a really interesting issue. I'm glad you asked me this because I think it's got good foresight. The big ethics fight now is scarcity and who goes first, and the ethicists, including me, are having a fine old time arguing about healthcare workers versus policemen versus people who work for UPS versus somebody who's working at the drug store. Who's more important? Why are they more important? Who's essential?

Actually, I think most of that is nonsense, because what we've learned is that you can't do much in the way of micro-allocation, the system strains, and it doesn't work. You've gotta use some pretty broad categories like over 65, still breathing and working, and a kid. The kid will go last, 'cause we don't have the data, everybody else should get in line and the over 65s should probably be first 'cause they're at high risk. We can't do this. We stink at the micro-management of vaccine supply, plus it encourages cheating. So everybody's out there with vaccine hunters, vaccine tourism, bribing, lying, dressing up like a grandmother to get a vaccine. My favorite one was some rich people in Vancouver flew up to the Yukon and pretended to be Inuit aboriginal people to get a vaccine. That will all pass.

We'll have enough vaccine by the summer, more or less, that the issue will then be, "How are we gonna get to herd immunity or at least maximal immunity, knowing that we don't have data on kids?" People under 18, I think are something like 20% of our population. That means the best you could do is 80%. The other population still could be passing the virus, kids here or Europe or wherever. Well, the military refusal rate that I just saw was 30% saying no. I've heard nursing home staff rates, nursing attendants, nursing aids up at 40% to 50% saying no. So these are huge refusal rates, people are nervous about how it works, the vaccine. Some of them are like, "Well Art you take it. If you're still alive in six months, then maybe I'll take it, but I wanna see that it really works and it's safe." And other people say, "We don't wanna be exploited. We don't trust the government, whatever, to offer us these vaccines."

I'm gonna answer that was a long-winded way of saying we're gonna see some mandates, we're gonna see some coercions start to show up in the vaccine supply, because I think, for example, the military. The day one of these license gets... Excuse me, one of these vaccines get licensed, right now they're on an emergency approval, collect data for three or four more months, get the FDA to formally license the thing. I'd say between five minutes and 10 minutes, the military will be mandating. They have no interest in your objection, they have no interest in your choice, they know what the mission is. It's traditionally, we're gonna get you as healthy as we can to fight a war.

The fact that you say, "Gee, I might die." They kind of say, "Yeah, we noticed that, but that's in the military culture. We fight wars and do stuff like that." So they'll be mandating, I think, very rapidly. And I think healthcare workers will. I think most hospitals are gonna say 50% refusal rate among this nursing group? Forget it. We can't risk that. Nursing homes have been devastated by COVID. They're not gonna have aids out there unvaccinated. The only thing holding up the mandates right now is that we don't have full licensure. We have emergency use approvals, and that's good.

But it's a little tough to mandate without full license. The day we get it, three months, four months, we're gonna start to see mandates. And I'll make one more prediction, as long as I'm in a crystal ball mode. It won't be the government at that point that says, you have to be vaccinated. It'll be private business, 'cause they're gonna say, "You know what? Come on my cruise ship, 'cause everybody who works here is vaccinated." "Come on into my bar, everybody who works here is vaccinated." They're gonna start to use it as an advertising marketing lure. "It's safe here. Come on in." So I think they'll say, "If you wanna work on an airline as a flight attendant, you get vaccinated. We have vaccine proof. You can show it on your iPhone, on your whatever, you have a card that you did it." And so I think we'll see many businesses moving to vaccinate so that they can bring their customers back in.

KIRA: So private businesses, that's one thing, because people do not have to patronize those places if they don't wanna get vaccinated. But of course, this is gonna open up a can of worms with schools. Public schools, if they mandate teacher vaccines and you have to send your kid to school and you have to go to work at a school. What happens then?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, schools are gonna be at the end of the line. That's where we have the least data. So I don't think we're gonna see school mandates on kids, maybe not till next year. But we already have school mandates on kids. They were the first group to feel the force of mandates, because it turns out that measles and mumps and whooping cough are easy to get at school, sneezing and coughing on one another. Some states have added flu shots. Many states, California, Maine, New York have actually eliminated exemptions. The only way out for those kids is if they have a health reason. They're not even allowing religious or so-called philosophical or personal choice exemptions. COVID vaccines will just line up right next to those things.

Teachers will demand it, the pressure will be there. We'll have a lot of information by next year on safety. I'm even gonna say people are gonna be less tolerant of non-vaccinators. Now it's sort of like, "Wow. Yeah, I guess." But this time next year, if you haven't vaccinated, people are gonna come to your house and board it up and make you stay inside.

KIRA: Well, given how much we're so dependent on these vaccines to get us back to a regular life, I can understand the sentiment. What is your take on the big controversy right now, just going back towards the present day a little bit more on having kids in schools. Is that something you support before all the teachers have been vaccinated?

DR. CAPLAN: I do, but I have a problem with the definition of a teacher and a school. So by the way, some people that I know, friends of mine have said, "Well, I'm a teacher, I'm a yoga instructor. I'm a teacher, I'm an aerobics instructor. So I should get priority access to vaccination." I don't think that's what we meant by teacher. And here's the difference in schools. I live in Ridgefield, Connecticut. Up the street for me is a very fancy private elementary school. It has endless grounds, open classrooms. If there are eight kids in a class, I'll pass out. It is great. I wish I went to college there. It's a wonderful set up. Do they need to vaccinate everybody? Probably not, they're all sitting six feet apart, everybody in there is gonna mask, they have huge auditoriums. They never have to come in contact.

I've been in some other schools in the Bronx. No ventilation, no plumbing, 35 kids in a class, the teacher's 65. And you sort of think, "Boy, I'd wanna have vaccinate everybody in sight in this place because unless we re-haul the buildings and downsize the class size, people are gonna get sick in here."

They probably were getting sick anyway before COVID, but now COVID makes it worse. They're probably getting the flu or colds at nine times the rate that they were in Ridgefield, Connecticut. So my point is this, high school kids doing certain things, they can come in on a mixed schedule three days a week, two days a week, do their thing, they know how to mask. Am I worried about vaccinating there? Not too much. Elementary school kids need psychosocial development, need to learn social skills, sometimes going to schools that aren't that wonderful. Yeah, let's vaccinate them. So even though I was complaining a bit about micro-management and trying to parse out, here I think you need to do it. I think you're probably gonna say college, I don't know that you have to vaccinate there. High schools, 50/50. Elementary school, let's do them first.

KIRA: Got it. And one more question on kids before I wanna move on, there's been talk about whether it's necessary before kids are allowed to get this vaccine to have the FDA go to full approval with the full bulk of data necessary for that versus just an emergency authorization for the general population, given that kids are at so much lower risk than adults. But then of course, it'll take a lot more time, I imagine, to get the kids the vaccines. What's your take on that?

DR. CAPLAN: We historically have demanded higher levels of evidence to do anything with a kid, and I think that's gonna hold true here too. I don't think you're gonna see emergency-use authorization for people under 18. Maybe they'd cut it and say, "We'll do it 12-18," but just looking at the history of drug development, vaccine development, people are really leery of taking risks with kids and appropriately so. Kids can't even make their own decision. I can decide if I wanna take an emergency-use vaccine, if I think it's too iffy I don't take it right now. So up to me to weigh the risk-benefit. I don't think so. I think you'll see licensing required before we really get it, at least 12 and under. Let's put it there. And I'm not worried about the safety or efficacy of these things in kids. I think there's no reason, given the biological mechanisms, to think they're gonna be any different. But it's gonna be pretty tough pre-licensure to impose anything.

KIRA: And when do you think that licensure for kids under 12 could come?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, two groups of people are now being studied, pregnant women, the studies just launched. They'll probably be done sufficiently by the end of the year. Kids for full licensure, spring next year.

KIRA: Okay. And because this is a big question for a lot of women that I know and women in general who are pregnant, what would you say to them now, where we don't have the data yet on the safety, but they have to decide and they can't wait six or nine more months?

DR. CAPLAN: Vaccinate yesterday. Literally, I think the COVID virus is too dangerous, I think it's dangerous to the mom, I think it's dangerous to the fetus. It is an unknown, but boy, I would bet on the vaccine more than I would taking my chances with the virus.

KIRA: Got it. So let's pivot a little bit and talk about some of the big open questions around the vaccines that we're starting to get some early evidence about. For one thing, do they prevent transmission and not just symptomatic disease. And I think it's worth pointing out for our audience here that there is a big difference between preventing symptoms and preventing infections, as lots of asymptomatic people know. And we have a lot of new real-world evidence from Israel, from Scotland, reporting that even asymptomatic infections are greatly reduced by the Pfizer vaccine, for example. What is your take on how this new data is going to change guidance around post-vaccination behaviors?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. What do we got in the podcast? Seven or eight hours to go? That's a tough one. It's complicated. But trying to over-simplify a little bit. So there is a difference, and this has gotten confusing, I fear. Some vaccines prevent you from getting infected at all. It looks like the Pfizer and the Moderna fall into that category. That's great, 'cause no matter what else, it probably means you're gonna reduce transmission, 'cause if you can't be infected, I don't know how you're gonna give it to somebody else. So I'll bet that that's a transmission reduction. Looks like Johnson & Johnson, unclear. Seems to prevent bad symptoms and death but not moderate disease, and it isn't clear that it stops you from getting infected. So that may become an issue in terms of how we strategically approach when we have enough vaccine of the different types. We may wanna say, "Look, in some environments, we've gotta control spread... Nursing home. We wanna see the Moderna there. We wanna see the Pfizer there."

In other situations, we just wanna make sure you're not dead, let's get the Janssen thing out there. And that'll be great. I'll tell you... I'll give you an example from my own current existence. So I've been pretty cautious... As I said, I live in Ridgefield, Connecticut. I have a house, pretty roomy, but I haven't left it very often. I'm willing to take the chance to go shopping. I'll confess I'm even willing to take the chance wearing a mask to go to the drug store and I've had a hair-cut or two. So I've been not hyper-cautious, but cautious. I don't invite people over that I don't know where they've been, so to speak. But now I'm vaccinated, and my wife is fully vaccinated. And the other night for the first time, we went out to an indoor restaurant. Probably haven't done that in 10 months... No, I don't know, six months. But a long time...

KIRA: I hope you really enjoyed that first meal out, 'cause that's something that I dream about. Boy, where am I gonna go and what am I gonna order?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. We went to the fanciest restaurant in town, as a matter of fact, and they were social distancing and everybody was masked and the wait staff. But I figure, good enough for me. If the thing isn't gonna kill me, if I was just told I was gonna have a risk of being sick for three days or something, that's good enough for me. I don't wanna infect somebody else. So I'll still mask and do that, I'm not sure. But I'm absolutely ready to say, and in fact, I've scheduled two trips. We're gonna take a trip to Florida, we're gonna take a trip to North Carolina in March and April. I'm figuring even then, things will be better. But everybody's gonna have choices like that to make. It'll be really interesting. If I'm Tony Fauci or one of our big public health guys, I don't want anybody going anywhere, I'm risk-averse, until maybe 2027. I think it'll be controlled and eliminated... We'll have lots of data and everything will be great. I'm a little bit more, shall we say, individual choice-oriented, making individual risk things, like I said. As long as I'm responsible to others.

I don't wanna make anybody else sick, but if I am ready to take the chance of just being sick for a few days, and I believe the vaccines available will keep me out of the hospital and keep me out of the Morticians building. Okay, I'm ready to do it. So each one of us is gonna have to make a value decision, this is what I find interesting, about what's normal. It isn't science. It isn't medicine. It's ethics. You're gonna have to decide how much risk do you wanna take. Do you wanna be a jerk to your neighbor, if you could still have a teeny chance of infecting them? Am I willing to live in a world where COVID is around but it's kinda rare? I know kids are still transmitting, but it's not really a huge risk. That's the kind of value choice that each of us will be faced with.

KIRA: I really appreciate your emphasis on individual choice and values here and letting... Basically allowing people to make those judgments based on their circumstances for themselves. If you're not deathly afraid of getting a mild cold-type illness, then I can understand why you wanna fly or go to a restaurant, and other people might not be comfortable with any risk at all, and they're perfectly welcome to stay home.

DR. CAPLAN: Or they may say, "I'm 80, I have nine chronic diseases. A mild illness still freaks me out." Okay, I get that. I'm perfectly respectful of that. It's interesting. I think we've been used to public health messaging, and people have this attitude that at some point, Fauci or the head of the CDC, somebody's gonna show up on TV and say, "All clear, everything's over, back to normal, we've declared victory over the enemy. It's armistice day." Whatever. It isn't gonna work like that is my prediction. It's gonna be a slow creep, different people deciding, "I'm safe enough, I'm wandering out." Other people say, "No, no, not ready." Or somebody saying, "I'm pregnant. I'm staying in. I don't care what's going on. I'm not gonna take that risk." I think people will be surprised that there isn't going to be a national day of resolution or something. [chuckle]

KIRA: Right. It's more about these individual behaviors and over time, letting people decide what to do. So for example, if you had grandkids and they were not vaccinated, but you are, would you hug them, would you get close to them, how would you behave and how do you think they should behave around you?

DR. CAPLAN: So I'd be still nervous about them transmitting, but I'm also a very strong believer in my vaccine. So yes, I would hug them, and yes, I would have them come to visit. And that's probably gonna happen actually fairly soon. But their parents aren't vaccinated yet. And so I'm still nervous that maybe better not to do a lot of social mingling right now. But yeah, people have said to me, "My grandmom is 94. I don't know how long she's gonna be here. You think if I'm vaccinated it's okay to pay a visit." I'm gonna start to say, "Yeah, I get that."

KIRA: And I think one thing that's lost in these discussions of safety is also the aspect of benefits to human life and why we even live in the first place. We don't live lives of complete safety. We drive, we fly, we do things that are risky, but we take those risks, because it's worth it. So I think that should be part of the discussion overall, not just safety, period.

DR. CAPLAN: And not just saving lives. So ski slopes, there are a lot of orthopedic clinics at the bottom of big ski slopes, and sending a message like, "You can break bones here." But people say, "I wanna do it, I enjoy it." Okay, I'm not sure all the time that we should factor all of that into our pooled insurance plan, but that's a fight for another day. Nonetheless, I would... You know something, I would pay for it 'cause I like to encourage people to enjoy themselves. So I have my bad habits, they have their bad habits. I think it's sort of a wash in a certain way. But more to your point, I think if you look out there and say, there are some areas where we don't let you choose. You must put your kid in a car seat. A kid can't make a decision, the thing is very effective, really saves their lives, they should have a life ahead of them, and we're gonna force it. And I'm all for that.

In other instances, I might go into the restaurant. I think it's part of the general, "Am I gonna drive a car, am I gonna cross a busy street... " As you said, there are many things I have to do where I have to think about the risk-benefit. I may make a lousy calculation and underestimate what it means to get in my car and drive in terms of risk relative to getting hit by lightening or some other risks, but that's a little bit more for me.

KIRA: So that's a really thought-provoking conversation, but I wanna switch for a minute to another question mark around the vaccines besides transmission, is the long-term studies of their effects on the immune system. And one thing that I've noticed some experts are concerned about is the fact that a lot of the people in the placebo groups have dropped out of the trials and gotten the vaccine because ethically you can't withhold the vaccinations from these volunteers, but at the same time, that could be hurting our ability to compare the vaccine's long-term effects against people who haven't had the vaccine for a long time. So how significant is this issue in your mind?

DR. CAPLAN: Big. Some people actually proposed that we not let them drop out, we not tell the subjects in these big trials of vaccines if they were in the placebo group. Can't do that. It's clearly unethical... Achieved consensus on that decades ago, with various studies where the researcher said, "We don't have to tell the subjects that there's a treatment." Tuskegee did that, for example, the horrible study in the early, late '60s, early '70s, where they didn't tell people there was a cure and kept the study going of venereal disease, but there have been many others since. We already know you gotta give them the option. Some people may stay in anyway, but not enough to allow the study to really have integrity. So I think current studies are likely to fall apart and we won't get answers in the way we're used to with randomized trials to the long-term effects or even to the how long does it last question.

We need to build a system that can follow people. We can't rely on them being in an observed clinical trial. We have to start to say, "You register, we're gonna check on you every year to see how you're doing." That's gotta be done. And one other provocative idea, I pushed it long ago, challenge studies. Deliberately infect a small group of people, hopefully healthy people that choose to do it with mild COVID and then see what the vaccine does in them and then get an answer faster if you study them over time, they volunteered knowingly to get exposed this way. I think you're gonna see some challenge studies done particularly to compare vaccines. There are still more vaccines coming, maybe some of them will last longer, cheaper, safer, I don't know. The only way you're gonna study the next round of vaccines is in a challenge study. You're never getting anybody to sign up to be in a placebo control randomized trial.

KIRA: So that was actually my next question, that the UK just approved the first ever challenge study to infect the volunteers on purpose with the virus. Now, the UK has often been much more progressive in doing medical research than the US. Do you think the US will ever get to that point or are we just gonna rely on other countries to do that for us?

DR. CAPLAN: I think we won't get there. We're so conservative, so litigation conscious. People are freaked out that if somebody got sick and died in a challenge study, it would bankrupt the sponsor. I think the UK is on the right path, but I don't really think we're gonna follow.

KIRA: Okay, well, I hope that they can do the work that we really need. And I'm grateful that there are other countries that are more permissive of risk-taking and doing the controversial studies that are required.

DR. CAPLAN: Ironically, if you don't do the challenge studies, the only other way you're gonna get to do big-scale randomized placebo trials is in the poorest countries that can't get anything. And that makes it an awful lot like exploitation, taking advantage, as opposed to choice. But that's where you'd go, you'd say, "Oh, I got this new vaccine, I'll test it out in Sierra Leone and they don't have anything anyway. So better that half of them get the vaccine than not." And I still think the challenge study makes more ethic sense.

KIRA: Yeah, absolutely. That would really be a shame to be put in that position instead of just allowing people to decide. We let people sign up for the army where they might die. What's the ethical difference with signing up for a potentially dangerous study, but if you're young and healthy, the risk is low?

DR. CAPLAN: By the way, the risk from COVID to say, 18 to 35-year-olds, who's who you'd be looking at, is about the same as donating a kidney, which we also allow all the time.

KIRA: Right, right. Great point. Before we finish up here, I just wanna quickly touch on, of course, the big elephant in the room, which we all have to deal with, unfortunately, which is the variants. So I wanna talk about where we stand. I've heard some vaccine experts recently say, like Paul Offit, for example, has said he doesn't expect a fourth surge due to this, but others are more cautious and take the flip side saying, "This is the calm before the storm. We're about to see another huge explosion." California has recently reported a new strain as accounts for maybe potentially 50% of cases now, and it could be 90% by the end of March. But we're seeing such big declines in the numbers in hospitalizations, in cases. So what should people make of these conflicting messages?

DR. CAPLAN: There's an attitude in medicine that many doctors take toward things like incipient or new prostate cancer, sometimes toward breast cancer, or at least lumps. It's called watchful waiting. You pay attention. You watch what's going on. But you don't do anything right away. I would still get vaccinated, I would still take what I could get. I still believe that it's likely that these vaccines are gonna provide some protection, if not against infection, then at least against the worst symptoms and the worst chances of dying because they're really gonna boost up the basic immune system, which should be able to start to fight against viruses.

That said, could we wind up with some virulent new strain that evades the current vaccine platforms? Yes. Is it likely? I don't think so. But what it does mean is get ready to get boosters because the response to new strains that have been a result of viral mutations is you gotta adjust your vaccine. That's what we'll do. I hope it doesn't send us back into quarantine and isolation and distancing and all the rest of it as our only control. I'm hoping that the manufacturers can roll out boosters more quickly than the first round of vaccines.

KIRA: And the FDA has just said that the vaccine developers will not need to start over with new clinical trials to these boosters. So that will greatly expedite the process. And do you think that's the right call?

DR. CAPLAN: Yes, absolutely. You're not changing the fundamental nature of the vaccine platform, you're just tweaking, if you will, which chemistry responds to the virus. So yeah, I do.

KIRA: And one question then that necessarily everyone is gonna wonder is, "Well, if I got the J&J vaccine, can I get an mRNA booster?" Can you mix and match? Is that gonna work for your immune system?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. We don't have any idea. And I wouldn't do that right away. I know some countries are thinking about that to get more, if you will, use out of a limited supply. I'd say wait three months and do it the right way, where the data is in evidence. I'm not worried about people getting a second shot of something different and dropping dead. I'm just worried that it won't work. [chuckle] So I'm not a fan of mix and match. You can do it in some studies, by the way. You could do it in some challenge studies and get a faster answer than you would having to try and do this in 30,000 people over a year. But no, I don't think that's a good way to go. And I'm not a big fan of one-shot strategies either. I think, what we know is that the second shot really kicks your immune system into high gear and that's what you want for real protection. So I know why people say it but I wouldn't advocate for it.

KIRA: Right. And for my last question. One of our big themes this year that we'll be following all throughout the year at leaps.org is our progress towards an eventual return to life and return to normalcy. So I have to ask that question to you. Given everything that you know and that we've discussed today, when do you think our lives and society will start to look normal again, with schools, and restaurants, and businesses open, people are flying and gathering without fear, traveling, etcetera?

DR. CAPLAN: I think you're gonna see a lot of that this summer. There's gonna be enough vaccine out there, even if the epidemiologists aren't 100% happy. As I said, I think a lot of people are gonna say, "I'm happy enough, good enough for me. I'm going to sports and I'm flying, and I'm taking a vacation." And we'll be outside again. Remember we had the ability to eat outdoors and congregate less when the weather's better around the whole country, and I think that will open up Europe and the US in addition. What I'm worried about is if we had to go back in the fall to a more controlled environment, either 'cause a new strain appeared, or just because things weren't as efficacious as we hoped they'd be. But I think summer is gonna be good this year.

KIRA: Well, I hope you're right. I hope your crystal ball is working today. [chuckle]

DR. CAPLAN: [chuckle] And if it's not working right, email Kira. Don't talk to me.

KIRA: Yeah, I cannot be held liable for this. Thank you Art for a fascinating discussion. And thanks to everyone for listening. If you like this show, follow Making Sense of Science to hear new episodes coming once a month. And if you wanna give us feedback, we'd love to hear from you. Get in touch on our website, leaps.org. And until next time, thanks everyone.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A Doctor Who Treated His Own Rare Disease Is Tracking COVID-19 Treatments Hiding In Plain Sight

Dr. David Fajgenbaum looking through a microscope at his lab.

In late March, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was ramping up in the United States, David Fajgenbaum, a physician-scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, devised a 10-day challenge for his lab: they would sift through 1,000 recently published scientific papers documenting cases of the deadly virus from around the world, pluck out the names of any drugs used in an attempt to cure patients, and track the treatments and their outcomes in a database.

Before late 2019, no one had ever had to treat this exact disease before, which meant all treatments would be trial and error. Fajgenbaum, a pioneering researcher in the field of drug repurposing—which prioritizes finding novel uses for existing drugs, rather than arduously and expensively developing new ones for each new disease—knew that physicians around the world would be embarking on an experimental journey, the scale of which would be unprecedented. His intention was to briefly document the early days of this potentially illuminating free-for-all, as a sidebar to his primary field of research on a group of lymph node disorders called Castleman disease. But now, 11 months and 29,000 scientific papers later, he and his team of 22 are still going strong.

They're running a publicly accessible database called the CORONA Project (COvid19 Registry of Off-label & New Agents) that to date tracks 400 different COVID-19 treatments that have been tried somewhere in the world, along with the frequency of their use, and the outcomes.

"There's so many drugs being used all over the place, in different ways, with different outcomes," says Fajgenbaum. "We're trying to add some order to the madness."

20,000 people have accessed the registry—other physicians and researchers, those in the pharmaceutical industry, and even curious lay people—and the data are now being shared with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the hopes of launching large-scale trials that would lead to approving a constellation of treatment options for COVID-19 faster than any new drugs could come online.

"What David's group has done with the CORONA Project is on a scale that I don't think has ever been seen before," says Heather Stone, a health science policy analyst at the FDA who specializes in drug repurposing. She was not involved in establishing the project, but is now working with its data. "To collect and collate that information and make it openly accessible is a massive feat, and a huge benefit to the medical community," she says.

On a Personal Mission

In the science and medical world, Fajgenbaum lives a dual existence: he is both researcher and subject, physician and patient. In July 2010, when he was a healthy and physically fit 25-year-old finishing medical school, he began living through what would become a recurring, unprovoked, and overzealous immune response that repeatedly almost killed him.

His lymph nodes were inflamed; his liver, kidneys, and bone marrow were faltering; and he was dead tired all the time. At first his doctors mistook his mysterious illness for lymphoma, but his inflamed lymph nodes were merely a red herring. A month after his initial hospitalization, pathologists at Mayo Clinic finally diagnosed him with idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease—a particularly ruthless form of a class of lymph node disorders that doesn't just attack one part of the body, but many, and has no known cause. It's a rare diagnosis within an already rare set of disorders. Only about 1,500 Americans a year receive the same diagnosis.

Without many options for treatment, Fajgenbaum underwent recurring rounds of chemotherapy. Each time, the treatment would offer temporary respite from Castleman symptoms, but bring the full spate of chemotherapy side effects. And it wasn't a sustainable treatment for the long haul. Regularly dousing a person's cells in unmitigated toxicity was about as elegant a solution to Fajgenbaum's disease as bulldozing a house in response to a toaster fire. The fire might go out (though not necessarily), but the house would be destroyed.

A swirl of exasperation and doggedness finally propelled Fajgenbaum to take on a crucial question himself: Among all of the already FDA-approved drugs on the market, was there something out there, labeled for another use, that could beat back Castleman disease and that he could tolerate long-term? After months of research, he discovered the answer: sirolimus, a drug normally prescribed to patients receiving a kidney transplant, could be used to suppress his overactive immune system with few known side effects to boot.

Fajgenbaum became hellbent on devoting his practice and research to making similar breakthroughs for others. He founded the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network, to coordinate the research of others studying this bewildering disease, and directs a laboratory consumed with studying cytokine storms—out-of-control immune responses characterized by the body's release of cytokines, proteins that the immune system secretes and uses to communicate with and direct other cells.

In the spring of 2020, when cytokine storms emerged as a hallmark of the most severe and deadly cases of COVID-19, Fajgenbaum's ears perked up. Although SARS-CoV-2 itself was novel, Fajgenbaum already had almost a decade of experience battling the most severe biological forces it brought. Only this time, he thought, it might actually be easier to pinpoint a treatment—unlike Castleman disease, which has no known cause, at least here a virus was clearly the instigator.

"Because [a drug] looks promising, we need to do a well-designed, large randomized controlled trial to really investigate whether this drug works or not ... We don't use that to say, 'You should take it.'"

Thinking Beyond COVID

The week of March 13, when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, Fajgenbaum found himself hoping that someone would make the same connection and apply the research to COVID. "Then like a minute later I was like, 'Why am I hoping that someone, somewhere, either follows our footsteps, or has a similar background to us? Maybe we just need to do it," he says. And the CORONA Project was born—first as a 10-day exercise, and later as the robust, interactive tool it now is.

All of the 400 treatments in the CORONA database are examples of repurposed drugs, or off-label uses: physicians are prescribing drugs to treat COVID that have been approved for a different disease. There are no bonafide COVID treatments, only inferences. The goal for people like Fajgenbaum and Stone is to identify potential treatments for further study and eventual official approval, so that physicians can treat the disease with a playbook in hand. When it works, drug repurposing opens up a way to move quickly: A range of treatments could be available to patients within just a few years of a totally new virus entering our reality compared with the 12 - 19 years new drug development takes.

"Companies for many decades have explored the use of their products for not just a single indication but often for many indications," says Stone. "'Supplemental approvals' are all essentially examples of drug repurposing, we just didn't call it that. The challenge, I think, is to explore those opportunities more comprehensively and systematically to really try to understand the full breadth of potential activity of any drug or molecule."

The left column shows the path of a repurposed drug, and on the right is the path of a newly discovered and developed drug.

Cures Within Reach

In Fajgenbaum's primary work, promising drugs stand out easily. For a disease like Castleman, where improvement almost never occurs on its own, any improvement that follows a treatment can pretty clearly be attributed to that treatment. But Fajgenbaum says tracking COVID outcomes is less straightforward since "the vast majority of people will get better, whether they take steroids or they take Skittles." That's why the intent of the database is to identify promising treatments only to generate hypotheses and fruitful clinical trials, not to offer full-throated treatment recommendations. Within the registry, Fajgenbaum considers a drug promising if it's being used in humans, not just in lab animals, and a significant proportion of cases report patient improvement.

"It's that sort of combination of rock-solid randomized controlled trial data, plus anecdotal retrospective data, that we combine to say, 'Wow, this drug looks more promising than another,'" says Fajgenbaum. "Because it looks promising, we need to do a well-designed, large randomized controlled trial to really investigate whether this drug works or not ... We don't use that to say, 'You should take it.'"

Experts say that the search for repurposed drugs to treat COVID could have implications for rare diseases in general. Rare diseases, of which Castleman is one, affect 400 million people around the world. 95% of them don't have a tailor-made, FDA-approved drug treatment. Developing one is a lengthy and often prohibitively expensive process. If only a dozen people will benefit from and buy a drug, it's not often worth it to pharmaceutical companies to spend millions of dollars making them. On occasion when they do, however, that overhead shows up in the price tag: the top 10 most expensive drugs in the world are all for rare diseases, often making them inaccessible to patients. Identifying new clinical uses for drugs that already exist is critical for opening a trap door out of a cycle that prioritizes profits over health outcomes.

"COVID is an interesting case where it's demonstrated that when the scientific and medical community really focuses all of its efforts and talents on a single problem, a solution can be identified and in a much faster time period than has ever historically been the case," says Stone. "I certainly wish it hadn't taken a pandemic to do that, but I think it does have lessons for the future in terms of our ability to accomplish things that we might have previously not thought were possible"—for example, mainstreaming the idea of drug repurposing as a treatment tool, even long after the pandemic subsides.

A Confounding Virus

The FDA declined to comment on what drugs it was fast-tracking for trials, but Fajgenbaum says that based on the CORONA Project's data, which includes data from smaller trials that have already taken place, he feels there are three drugs that seem the most clearly and broadly promising for large-scale studies. Among them are dexamethasone, which is a steroid with anti-inflammatory effects, and baricitinib, a rheumatoid arthritis drug, both of which have enabled the sickest COVID-19 patients to bounce back by suppressing their immune systems. The third most clearly promising drug is heparin, a blood thinner, which a recent trial showed to be most helpful when administered at a full dose, more so than at a small, preventative dose. (On the flipside, Fajgenbaum says "it's a little sad" that in the database you can see hydroxychloroquine is still the most-prescribed drug being tried as a COVID treatment around the world, despite over the summer being debunked widely as an effective treatment, and continuously since then.)

One of the confounding attributes of SARS-CoV-2 is its ability to cause such a huge spectrum of outcomes. It's unlikely a silver bullet treatment will emerge under that reality, so the database also helps surface drugs that seem most promising for a specific population. Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor used to treat obsessive compulsive disorder, showed promise in the recovery of outpatients—those who were sick, but not severely enough to be hospitalized. Tocilizumab, which was actually developed for Castleman disease, the disease Fajgenbaum is managing, was initially written off as a COVID treatment because it failed to benefit large portions of hospitalized patients, but now seems to be effective if used on intensive care unit patients within 24 hours of admission—these are some of the sickest patients with the highest risk of dying.

Other than fluvoxamine, most of the drugs labeled as promising do skew toward targeting hospitalized patients, more than outpatients. One reason, Fajgenbaum says, is that "if you're in a hospital it's very easy to give you a drug and to track you, and there are very objective measurements as to whether you die, you progress to a ventilator, etc." Tracking outpatients is far more difficult, especially when folks have been routinely asked to stay home, quarantine, and free up hospital resources if they're experiencing only mild symptoms.

But the other reason for the skew is because COVID is very unlike most other diseases in terms of the human immune response the virus triggers. For example, if oncology treatments show some benefit to people with the highest risk of dying, then they usually work extremely well if administered in the earlier stages of a cancer diagnosis. Across many diseases, this dialing backward is a standard approach to identifying promising treatments. With COVID, all of that reasoning has proven moot.

As we've seen over the last year, COVID cases often start as asymptomatic, and remain that way for days, indicating the body is mounting an incredibly weak immune response initially. Then, between days five and 14, as if trying to make up for lost time, the immune system overcompensates by launching a major inflammatory response, which in the sickest patient can lead to the type of cytokine storms that helped Fajgenbaum realize his years of Castleman research might be useful during this public health crisis. Because of this phased response, you can't apply the same treatment logic to all cases.

"In COVID, drugs that work late tend to not work if given early, and drugs that work early tend to not work if given late," says Fajgenbaum. "Generally this … is not a commonplace thing for a virus."

"There are drugs that are literally sitting in every single hospital pharmacy in the country that, if a study shows it's effective, can be deployed that evening to patients on a massive scale."

This see-sawing necessitates tracking a constellation of drugs that might work for different stages of the disease as a patient moves from the weak immune response stage into the overzealous immune response.

"COVID is difficult, compared to other diseases, because there are so many different levels of disease severity, and recovery at different rates," says Stone, the FDA researcher. "That makes it hard to see the patterns or signals and it makes it very important to collect very, very large numbers of cases in order to really reliably identify signals."

This particular moment in the pandemic feels like a massive tipping point, or the instant a tiny pinprick of light finally appeared at the end of the tunnel: several vaccines are already here, with more on the way imminently. In the U.S., more than 65 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, and positive COVID cases are finally falling back to levels not seen since October. On the hopeful surface, it might seem a strange moment to be preparing to launch trials that will validate treatments for a virus it seems the U.S. may finally be beating back. But at best, Americans are still months away from reaching herd immunity through vaccination, and new circulating variants may threaten to upend our fragile progress.

"In the meantime, there are drugs that are literally sitting in every single hospital pharmacy in the country that, if a study shows it's effective, can be deployed that evening to patients on a massive scale. It wouldn't have to be newly produced, it wouldn't have to be shipped, it's literally there already," says Fajgenbaum. "The idea that you can save a lot of lives by finding things that are just already there I think is really compelling, given how many people are going to die over these next few months."

Even after that, not everyone can or will be vaccinated, and, as the Wall Street Journal recently reported, "The pathogen will circulate for years, or even decades, leaving society to coexist with Covid-19 much as it does with other endemic diseases like flu, measles, and HIV." Neither vaccines, personal behavior, or treatments alone is a panacea against the virus, but together they might be.

"It's important to explore all avenues in this public health emergency, and drug repurposing can continue to play a role as the pandemic continues and evolves," says Stone. "I think COVID variants in particular are a big concern at the moment, and therefore continuing to investigate new therapeutics, even as the vaccines roll out, will continue to be a priority."