How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

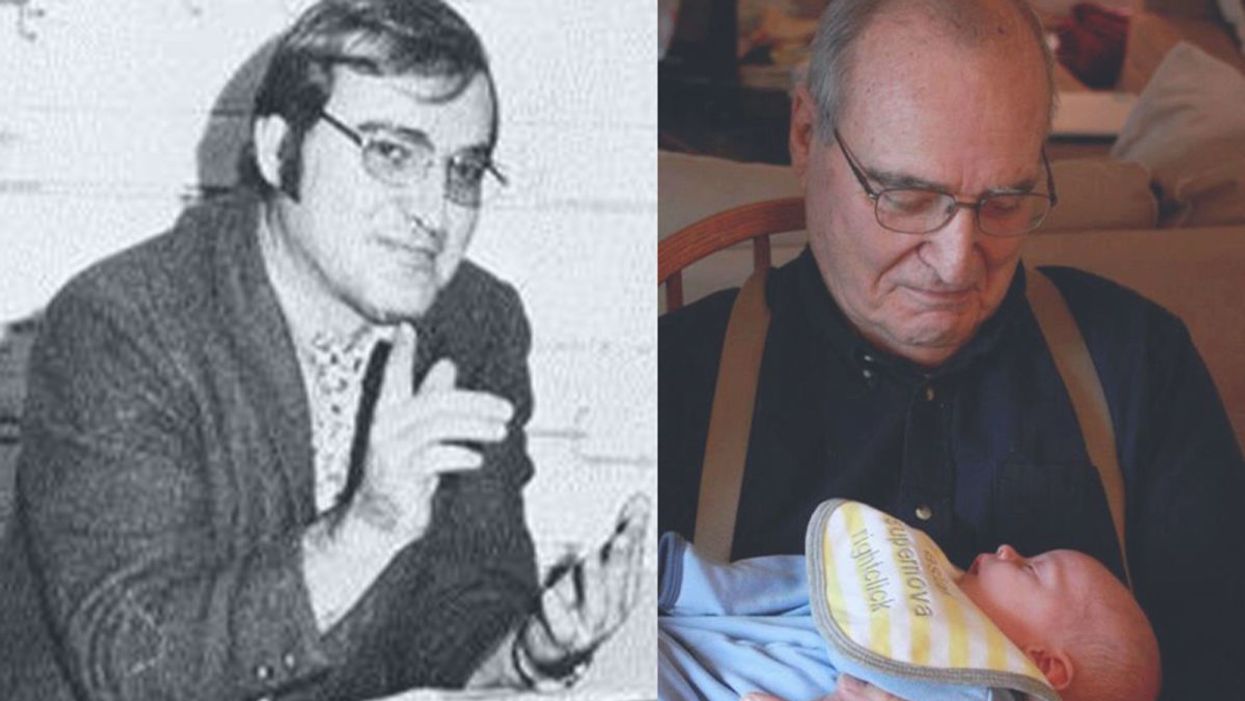

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

How a Nobel-Prize Winner Fought Her Family, Nazis, and Bombs to Change our Understanding of Cells Forever

Rita Levi-Montalcini survived the Nazis and eventually won a Nobel Prize for her work to understand why certain cells grow so quickly.

When Rita Levi-Montalcini decided to become a scientist, she was determined that nothing would stand in her way. And from the beginning, that determination was put to the test. Before Levi-Montalcini became a Nobel Prize-winning neurobiologist, the first to discover and isolate a crucial chemical called Neural Growth Factor (NGF), she would have to battle both the sexism within her own family as well as the racism and fascism that was slowly engulfing her country

Levi-Montalcini was born to two loving parents in Turin, Italy at the turn of the 20th century. She and her twin sister, Paola, were the youngest of the family's four children, and Levi-Montalcini described her childhood as "filled with love and reciprocal devotion." But while her parents were loving, supportive and "highly cultured," her father refused to let his three daughters engage in any schooling beyond the basics. "He loved us and had a great respect for women," she later explained, "but he believed that a professional career would interfere with the duties of a wife and mother."

At age 20, Levi-Montalcini had finally had enough. "I realized that I could not possibly adjust to a feminine role as conceived by my father," she is quoted as saying, and asked his permission to finish high school and pursue a career in medicine. When her father reluctantly agreed, Levi-Montalcini was ecstatic: In just under a year, she managed to catch up on her mathematics, graduate high school, and enroll in medical school in Turin.

By 1936, Levi-Montalcini had graduated medical school at the top of her class and decided to stay on at the University of Turin as a research assistant for histologist and human anatomy professor Guiseppe Levi. Levi-Montalcini started studying nerve cells and nerve fibers – the tiny, slender tendrils that are threaded throughout our nerves and that determine what information each nerve can transmit. But it wasn't long before another enormous obstacle to her scientific career reared its head.

Science Under a Fascist Regime

Two years into her research assistant position, Levi-Montalcini was fired, along with every other "non-Aryan Italian" who held an academic or professional career, thanks to a series of antisemitic laws passed by Italy's then-leader Benito Mussolini. Forced out of her academic position, Levi-Montalcini went to Belgium for a fellowship at a neurological institute in Brussels – but then was forced back to Turin when the German army invaded.

Levi-Montalcini decided to keep researching. She and Guiseppe Levi built a makeshift lab in Levi-Montalcini's apartment, borrowing chicken eggs from local farmers and using sewing needles to dissect them. By dissecting the chicken embryos from her bedroom laboratory, she was able to see how nerve fibers formed and died. The two continued this research until they were interrupted again – this time, by British air raids. Levi-Montalcini fled to a country cottage to continue her research, and then two years later was forced into hiding when the German army invaded Italy. Levi-Montalcini and her family assumed different identities and lived with non-Jewish friends in Florence to survive the Holocaust. Despite all of this, Levi-Montalcini continued her work, dissecting chicken embryos from her hiding place until the end of the war.

"The discovery of NGF really changed the world in which we live, because now we knew that cells talk to other cells, and that they use soluble factors. It was hugely important."

A Post-War Discovery

Several years after the war, when Levi-Montalcini was once again working at the University of Turin, a German embryologist named Viktor Hamburger invited her to Washington University in St. Louis. Hamburger was impressed by Levi-Montalcini's research with her chicken embryos, and secured an opportunity for her to continue her work in America. The invitation would "change the course of my life," Levi-Montalcini would later recall.

During her fellowship, Montalcini grew tumors in mice and then transferred them to chick embryos in order to see how it would affect the chickens. To her surprise, she noticed that introducing the tumor samples would cause nerve fibers to grow rapidly. From this, Levi-Montalcini discovered and was able to isolate a protein that she determined was able to cause this rapid growth. She later named this Nerve Growth Factor, or NGF.

From there, Levi-Montalcini and her team launched new experiments to test NGF, injecting it and repressing it to see the effect it had in a test subject's body. When the team injected NGF into embryonic mice, they observed nerve growth, as well as the mouse pups developing faster – their eyes opening earlier and their teeth coming in sooner – than the untreated group. When the team purified the NGF extract, however, it had no effect, leading the team to believe that something else in the crude extract of NGF was influencing the growth of the newborn mice. Stanley Cohen, Levi-Montalcini's colleague, identified another growth factor called EGF – epidermal growth factor – that caused the mouse pups' eyes and teeth to grow so quickly.

Levi-Montalcini continued to experiment with NGF for the next several decades at Washington University, illuminating how NGF works in our body. When Levi-Montalcini injected newborn mice with an antiserum for NGF, for example, her team found that it "almost completely deprived the animals of a sympathetic nervous system." Other experiments done by Levi-Montalcini and her colleagues helped show the role that NGF plays in other important biological processes, such as the regulation of our immune system and ovulation.

"The discovery of NGF really changed the world in which we live, because now we knew that cells talk to other cells, and that they use soluble factors. It was hugely important," said Bill Mobley, Chair of the Department of Neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

Her Lasting Legacy

After years of setbacks, Levi-Montalcini's groundbreaking work was recognized in 1986, when she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her discovery of NGF (Cohen, her colleague who discovered EGF, shared the prize). Researchers continue to study NGF even to this day, and the continued research has been able to increase our understanding of diseases like HIV and Alzheimer's.

Levi-Montalcini never stopped researching either: In January 2012, at the age of 102, Levi-Montalcini published her last research paper in the journal PNAS, making her the oldest member of the National Academy of Science to do so. Before she died in December 2012, she encouraged other scientists who would suffer setbacks in their careers to keep pursuing their passions. "Don't fear the difficult moments," Levi-Montalcini is quoted as saying. "The best comes from them."

60-Second Video: How Safe Are the COVID-19 Vaccines?

Comparing the Risks of COVID-19 vs. the Risks of the Vaccines:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.