How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

Announcing "The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue"

This special magazine explores what's at stake for science & policy over the next four years.

As reviewed in The Washington Post, "Tomorrow's challenges in science and politics: Magazine offers in-depth takes on these U.S. issues":

"Is it time for a new way to help make adults more science-literate? What should the next president know about science? Could science help strengthen American democracy? "The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue" has answers. The free, online magazine is packed with interesting takes on how science can serve the common good. And just in time. This year has challenged leaders, researchers and the public with thorny scientific questions, from the coronavirus pandemic to widespread misinformation on scientific issues. The magazine is a collaboration of the Aspen Institute, a think tank that brings together a variety of public figures and private individuals to tackle thorny social issues, the digital science magazine Leapsmag and GOOD, a social impact company. It's packed with 15 in-depth articles about science with a view toward our campaign year."

The Future of Science in America: The Election Issue offers wide-ranging perspectives on challenges and opportunities for science as we elect our next national and local leaders. The fast-striking COVID-19 pandemic and the more slowly moving pandemic of climate change have brought into sharp focus how reliant we will be on science and public policy to work together to rescue us from crisis. Doing so will require cooperation between both political parties, as well as significant public trust in science as a beacon to light the path forward.

In spite of its unfortunate emergence as a flash point between two warring parties, we believe that science is the driving force for universal progress. No endeavor is more noble than the quest to rigorously understand our world and apply that knowledge to further human flourishing. This magazine aspires to promote roadmaps for science as a tool for health, a vehicle for progress, and a unifier of our nation.

This special issue is a collaboration among LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD, with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Rita Allen Foundation.

It is available as a free, beautifully designed digital magazine for both desktop and mobile.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

- SCIENTISTS:

Award-Winning Scientists Offer Advice to the Next President of the United States - PUBLIC OPINION:

National Survey Reveals Americans' Most Important Scientific Priorities - GOVERNMENT:

The Nation's Science and Health Agencies Face a Credibility Crisis: Can Their Reputations Be Restored? - TELEVISION:

To Make Science Engaging, We Need a Sesame Street for Adults - IMMIGRATION:

Immigrant Scientists—and America's Edge—Face a Moment of Truth This Election - RACIAL JUSTICE:

Democratize the White Coat by Honoring Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Science - EDUCATION:

I'm a Black, Genderqueer Medical Student: Here's My Hard-Won Wisdom for Students and Educational Institutions - TECHNOLOGY:

"Deep Fake" Video Technology Is Advancing Faster Than Our Policies Can Keep Up - VOTERS:

Mind the (Vote) Gap: Can We Get More STEM Students to the Polls? - EXPERTS:

Who Qualifies as an "Expert" and How Can We Decide Who Is Trustworthy? - SOCIAL MEDIA:

Why Your Brain Falls for Misinformation—And How to Avoid It - YOUTH:

Youth Climate Activists Expand Their Focus and Collaborate to Get Out the Vote - SUPREME COURT:

Abortions Before Fetal Viability Are Legal: Might Science and a Change on the Supreme Court Undermine That? - NAVAJO NATION:

An Environmental Scientist and an Educator Highlight Navajo Efforts to Balance Tradition with Scientific Priorities - CIVIC SCIENCE:

Want to Strengthen American Democracy? The Science of Collaboration Can Help

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Scientists Envision a Universal Coronavirus Vaccine

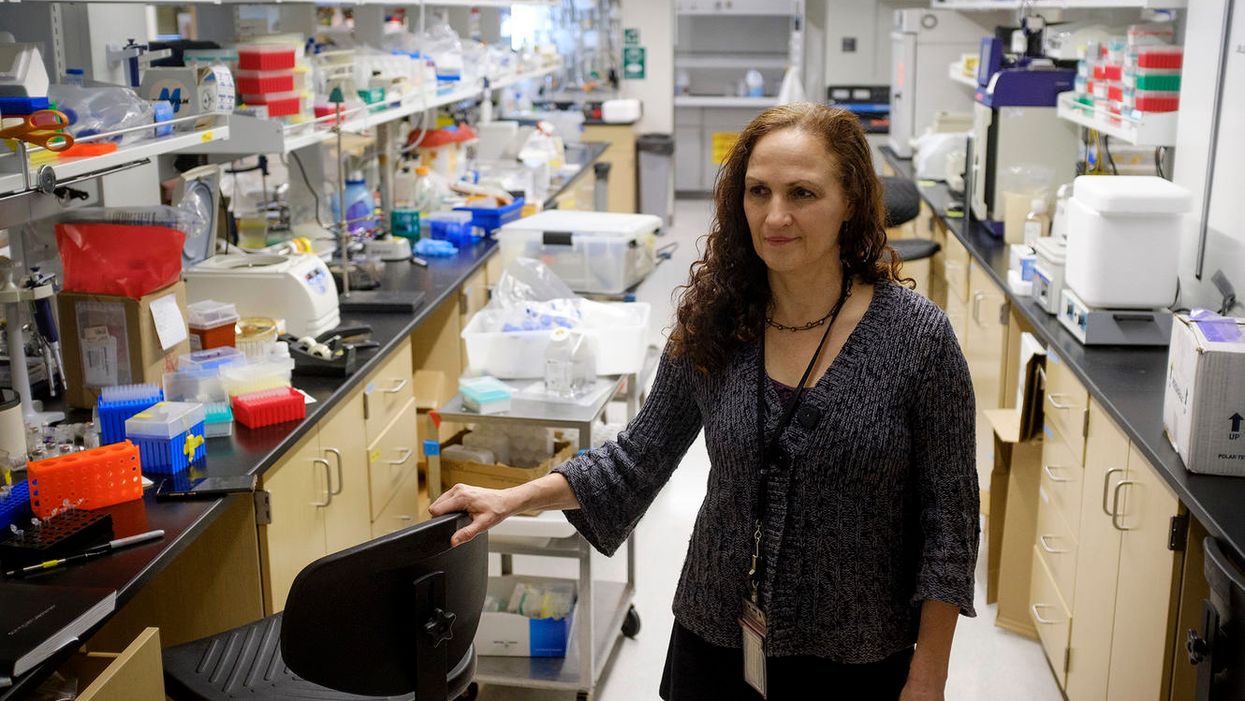

Dr. Deborah Fuller, a professor of microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine, in her lab.

With several companies progressing through Phase III clinical trials, the much-awaited coronavirus vaccines may finally become reality within a few months.

But some scientists question whether these vaccines will produce a strong and long-lasting immunity, especially if they aren't efficient at mobilizing T-cells, the body's defense soldiers.

"When I look at those vaccines there are pitfalls in every one of them," says Deborah Fuller, professor of microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine. "Some may induce only transient antibodies, some may not be very good at inducing T-cell responses, and others may not immunize the elderly very well."

Generally, vaccines work by introducing an antigen into the body—either a dead or attenuated pathogen that can't replicate, or parts of the pathogen or its proteins, which the body will recognize as foreign. The pathogens or its parts are usually discovered by cells that chew up the intruders and present them to the immune system fighters, B- and T-cells—like a trespasser's mug shot to the police. In response, B-cells make antibodies to neutralize the virus, and a specialized "crew" called memory B-cells will remember the antigen. Meanwhile, an army of various T-cells attacks the pathogens as well as the cells these pathogens already infected. Special helper T-cells help stimulate B-cells to secrete antibodies and activate cytotoxic T-cells that release chemicals called inflammatory cytokines that kill pathogens and cells they infected.

"Each of these components of the immune system are important and orchestrated to talk to each other," says professor Larry Corey, who studies vaccines and infectious disease at Fred Hutch, a non-profit scientific research organization. "They optimize the assault of the human immune system on the complexity of the viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic infections that live on our planet, to which we get exposed."

Despite their variety, coronaviruses share certain common proteins and other structural elements, Fuller explains, which the immune system can be trained to identify.

The current frontrunner vaccines aim to train our body to generate a sufficient amount of antibodies to neutralize the virus by shutting off its spike proteins before it enters our cells and begins to replicate. But a truly robust vaccine should also engender a strong response from T-cells, Fuller believes.

"Everyone focuses on the antibodies which block the virus, but it's not always 100 percent effective," she explains. "For example, if there are not enough titers or the antibody starts to wane, and the virus does get into the cells, the cells will become infected. At that point, the body needs to mount a robust T-cytotoxic response. The T-cells should find and recognize cells infected with the virus and eliminate these cells, and the virus with them."

Some of the frontrunner vaccine makers including Moderna, AstraZeneca and CanSino reported that they observed T-cell responses in their trials. Another company, BioNTech, based in Germany, also reported that their vaccine produced T-cell responses.

Fuller and her team are working on their own version of a coronavirus vaccine. In their recent study, the team managed to trigger a strong antibody and T-cell response in mice and primates. Moreover, the aging animals also produced a robust response, which would be important for the human elderly population.

But Fuller's team wants to engage T-cells further. She wants to try training T-cells to recognize not only SARV-CoV-2, but a range of different coronaviruses. Wild hosts, such as bats, carry many different types of coronaviruses, which may spill over onto humans, just like SARS, MERS and SARV-CoV-2 have. There are also four coronaviruses already endemic to humans. Cryptically named 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, they were identified in the 1960s. And while they cause common colds and aren't considered particularly dangerous, the next coronavirus that jumps species may prove deadlier than the previous ones.

Despite their variety, coronaviruses share certain common proteins and other structural elements, Fuller explains, which the immune system can be trained to identify. "T-cells can recognize these shared sequences across multiple different types of coronaviruses," she explains, "so we have this vision for a universal coronavirus vaccine."

Paul Offit at Children's Hospitals in Philadelphia, who specializes in infectious diseases and vaccines, thinks it's a far shot at the moment. "I don't see that as something that is likely to happen, certainly not very soon," he says, adding that a universal flu vaccine has been tried for decades but is not available yet. We still don't know how the current frontrunner vaccines will perform. And until we know how efficient they are, wearing masks and keeping social distance are still important, he notes.

Corey says that while the universal coronavirus vaccine is not impossible, it is certainly not an easy feat. "It is a reasonably scientific hypothesis," he says, but one big challenge is that there are still many unknown coronaviruses so anticipating their structural elements is difficult. The structure of new viruses, particularly the recombinant ones that leap from wild hosts and carry bits and pieces of animal and human genetic material, can be hard to predict. "So whether you can make a vaccine that has universal T-cells to every coronavirus is also difficult to predict," Corey says. But, he adds, "I'm not being negative. I'm just saying that it's a formidable task."

Fuller is certainly up to the task and thinks it's worth the effort. "T-cells can cross-recognize different viruses within the same family," she says, so increasing their abilities to home in on a broader range of coronaviruses would help prevent future pandemics. "If that works, you're just going to take one [vaccine] and you'll have lifetime immunity," she says. "Not just against this coronavirus, but any future pandemic by a coronavirus."

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.