How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

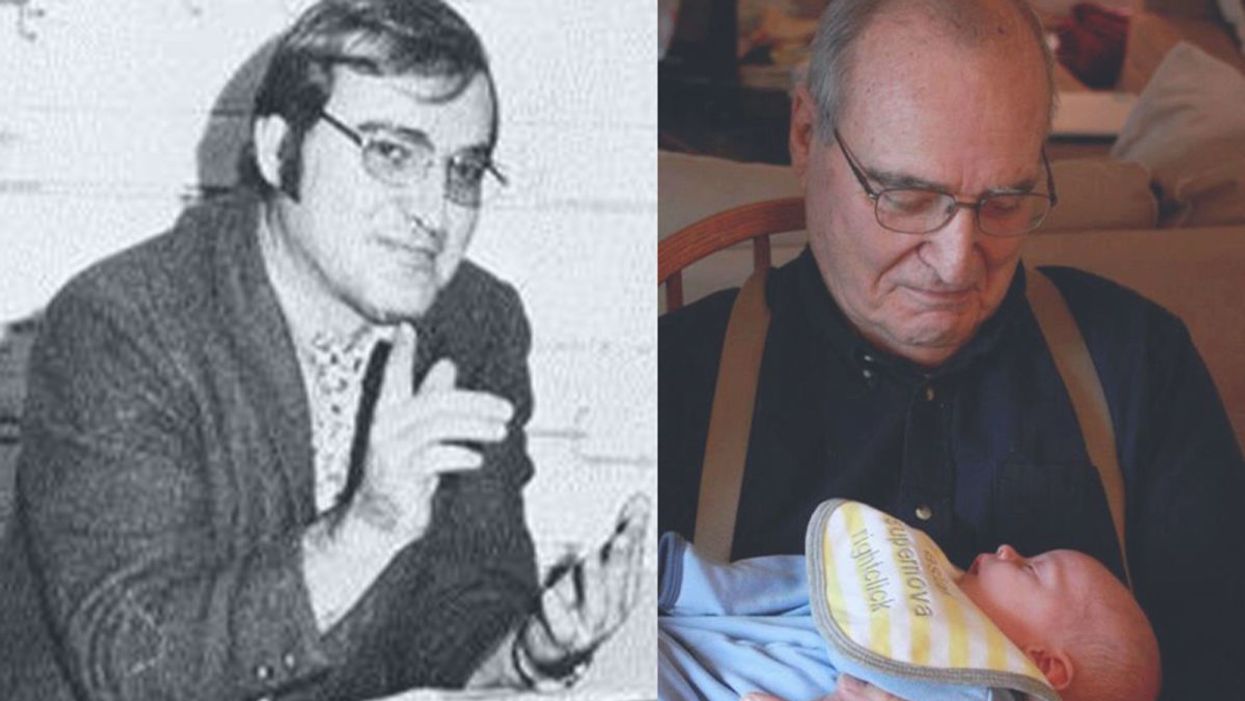

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

How Smallpox Was Wiped Off the Planet By a Vaccine and Global Cooperation

The world's last recorded case of endemic smallpox was in Ali Maow Maalin, of Merka, Somalia, in October 1977. He made a full recovery.

For 3000 years, civilizations all over the world were brutalized by smallpox, an infectious and deadly virus characterized by fever and a rash of painful, oozing sores.

Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success.

Smallpox was merciless, killing one third of people it infected and leaving many survivors permanently pockmarked and blind. Although smallpox was more common during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was still a leading cause of death even up until the early 1950s, killing an estimated 50 million people annually.

A Primitive Cure

Sometime during the 10th century, Chinese physicians figured out that exposing people to a tiny bit of smallpox would sometimes result in a milder infection and immunity to the disease afterward (if the person survived). Desperate for a cure, people would huff powders made of smallpox scabs or insert smallpox pus into their skin, all in the hopes of getting immunity without having to get too sick. However, this method – called inoculation – didn't always work. People could still catch the full-blown disease, spread it to others, or even catch another infectious disease like syphilis in the process.

A Breakthrough Treatment

For centuries, inoculation – however imperfect – was the only protection the world had against smallpox. But in the late 18th century, an English physician named Edward Jenner created a more effective method. Jenner discovered that inoculating a person with cowpox – a much milder relative of the smallpox virus – would make that person immune to smallpox as well, but this time without the possibility of actually catching or transmitting smallpox. His breakthrough became the world's first vaccine against a contagious disease. Other researchers, like Louis Pasteur, would use these same principles to make vaccines for global killers like anthrax and rabies. Vaccination was considered a miracle, conferring all of the rewards of having gotten sick (immunity) without the risk of death or blindness.

Scaling the Cure

As vaccination became more widespread, the number of global smallpox deaths began to drop, particularly in Europe and the United States. But even as late as 1967, smallpox was still killing anywhere from 10 to 15 million people in poorer parts of the globe. The World Health Assembly (a decision-making body of the World Health Organization) decided that year to launch the first coordinated effort to eradicate smallpox from the planet completely, aiming for 80 percent vaccine coverage in every country in which the disease was endemic – a total of 33 countries.

But officials knew that eradicating smallpox would be easier said than done. Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success. The vaccination initiative in Bangladesh proved the most challenging, due to its population density and the prevalence of the disease, writes journalist Laurie Garrett in her book, The Coming Plague.

In one instance, French physician Daniel Tarantola on assignment in Bangladesh confronted a murderous gang that was thought to be spreading smallpox throughout the countryside during their crime sprees. Without police protection, Tarantola confronted the gang and "faced down guns" in order to immunize them, protecting the villagers from repeated outbreaks.

Because not enough vaccines existed to vaccinate everyone in a given country, doctors utilized a strategy called "ring vaccination," which meant locating individual outbreaks and vaccinating all known and possible contacts to stop an outbreak at its source. Fewer than 50 percent of the population in Nigeria received a vaccine, for example, but thanks to ring vaccination, it was eradicated in that country nonetheless. Doctors worked tirelessly for the next eleven years to immunize as many people as possible.

The World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

A Resounding Success

In November 1975, officials discovered a case of variola major — the more virulent strain of the smallpox virus — in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl named Rahima Banu. Banu was forcibly quarantined in her family's home with armed guards until the risk of transmission had passed, while officials went door-to-door vaccinating everyone within a five-mile radius. Two years later, the last case of variola major in human history was reported in Somalia. When no new community-acquired cases appeared after that, the World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

Because of smallpox, we now know it's possible to completely eliminate a disease. But is it likely to happen again with other diseases, like COVID-19? Some scientists aren't so sure. As dangerous as smallpox was, it had a few characteristics that made eradication possibly easier than for other diseases. Smallpox, for instance, has no animal reservoir, meaning that it could not circulate in animals and resurge in a human population at a later date. Additionally, a person who had smallpox once was guaranteed immunity from the disease thereafter — which is not the case for COVID-19.

In The Coming Plague, Japanese physician Isao Arita, who led the WHO's Smallpox Eradication Unit, admitted to routinely defying orders from the WHO, mobilizing to parts of the world without official approval and sometimes even vaccinating people against their will. "If we hadn't broken every single WHO rule many times over, we would have never defeated smallpox," Arita said. "Never."

Still, thanks to the life-saving technology of vaccines – and the tireless efforts of doctors and scientists across the globe – a once-lethal disease is now a thing of the past.

Over 1 Million Seeds Are Buried Near the North Pole to Back Up the World’s Crops

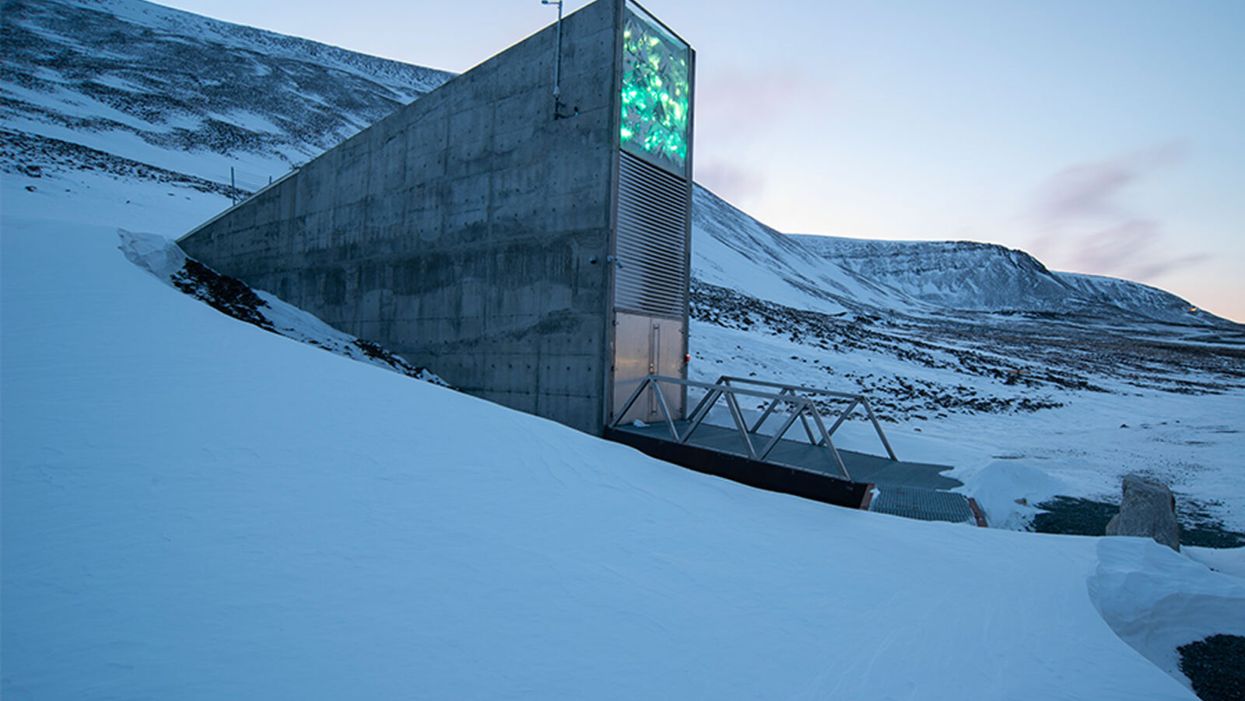

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault preserves more than one million of the world's seeds deep inside Platäfjellet Mountain.

The impressive structure protrudes from the side of a snowy mountain on the Svalbard Archipelago, a cluster of islands about halfway between Norway and the North Pole.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost. We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

Art installations on the building's rooftop and front façade glimmer like diamonds in the polar night, but it is what lies buried deep inside the frozen rock, 475 feet from the building's entrance, that is most precious. Here, in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, are backup copies of more than a million of the world's agricultural seeds.

Inside the vault, seed boxes from many gene banks and many countries. "The seeds don't know national boundaries," says Kent Nnadozie, the UN's Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

(Photo credit: Svalbard Global Seed Vault/Riccardo Gangale)

The Svalbard vault -- which has been called the Doomsday Vault, or a Noah's Ark for seeds -- preserves the genetic materials of more than 6000 crop species and their wild relatives, including many of the varieties within those species. Svalbard's collection represents all the traits that will enable the plants that feed the world to adapt – with the help of farmers and plant breeders – to rapidly changing climactic conditions, including rising temperatures, more intense drought, and increasing soil salinity. "We save these seeds because we want to ensure food security for future generations," says Grethe Helene Evjen, Senior Advisor at the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food .

A recent study in the journal Nature predicted that global warming could cause catastrophic losses of biodiversity in regions across the globe throughout this century. Yet global warming also threatens the permafrost that surrounds the seed vault, the very thing that was once considered a failsafe means of keeping these seeds frozen and safeguarding the diversity of our crops. In fact, record temperatures in Svalbard a few years ago – and a significant breach of water into the access tunnel to the vault -- prompted the Norwegian government to invest $20 million euros on improvements at the facility to further secure the genetic resources locked inside. The hope: that technology can work in concert with nature's freezer to keep the world's seeds viable.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost," says Hege Njaa Aschim, a spokesperson for Statsbygg, the government agency that recently completed the upgrades at the seed vault. "We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

The Apex of the Global Conservation System

More than 1700 genebanks around the globe preserve the diverse seed varieties from their regions. They range from small community seed banks in developing countries, where small farmers save and trade their seeds with growers in nearby villages, to specialized university collections, to national and international genetic resource repositories. But many of these facilities are vulnerable to war, natural disasters, or even lack of funding.

"If anything should happen to the resources in a regular genebank, Svalbard is the backup – it's essentially the apex of the global conservation system," says Kent Nnadozie, Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture at the United Nations, who likens the Global Vault to the Central Reserve Bank. "You have regular banks that do active trading, but the Central Bank is the final reserve where the banks store their gold deposits."

Similarly, farmers deposit their seeds in regional genebanks, and also look to these banks for new varieties to help their crops adapt to, say, increasing temperatures, or resist intrusive pests. Regional banks, in turn, store duplicates from their collections at Svalbard. These seeds remain the sovereign property of the country or institution depositing them; only they can "make a withdrawal."

The Global Vault has already proven invaluable: The International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), formerly located outside of Aleppo, Syria, held more than 140,000 seed samples, including plants that were extinct in their natural habitats, before the Syrian Crisis in 2012. Fortunately, they had managed to back up most of their seed samples at Svalbard before they were forced to relocate to Lebanon and Morocco. In 2017, ICARDA became the first – and only – organization to withdraw their stored seeds. They have now regenerated almost all of the samples at their new locations and recently redeposited new seeds for safekeeping at Svalbard.

Rapid Global Warming Threatens Permafrost

The Global Vault, a joint venture between the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) that started operating in 2008, was sited in Svalbard in part because of its remote yet accessible location: Svalbard is the northernmost inhabited spot on Earth with an airport. But experts also thought it a failsafe choice for long-term seed storage because its permafrost would offer natural freezing – even if cooling systems were to fail. No one imagined that the permafrost could fail.

"We've had record temperatures in the region recently, and there are a lot of signs that global warming is happening faster at the extreme latitudes," says Geoff Hawtin, a world-renowned authority in plant conservation, who is the founding director of -- and now advisor to -- the Crop Trust. "Svalbard is still arguably one of the safest places for the seeds from a temperature point of view, but it's actually not going to be as cold as we thought 20 years ago."

A recent report by the Norwegian Centre for Climate Services predicted that Svalbard could become 50 degrees Fahrenheit warmer by the year 2100. And data from the Norwegian government's environmental monitoring system in Svalbard shows that the permafrost is already thawing: The "active layer," that is, the layer of surface soil that seasonally thaws, has become 25-30 cm thicker since 1998.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization.

Though the permafrost surrounding the seed vault chambers, which are situated well below the active layer, is still intact, the permafrost around the access tunnel never re-established as expected after construction of the Global Vault twelve years ago. As a result, when Svalbard saw record high temperatures and unprecedented rainfall in 2016, about 164 feet of rainwater and snowmelt leaked into the tunnel, turning it into a skating rink and spurring authorities to take what they called a "better safe than sorry approach." They invested in major upgrades to the facility. "The seeds in the vault were never threatened," says Aschim, "but technology has become more important at Svalbard."

Technology Gives Nature a Boost

For now, the permafrost deep inside the mountain still keeps the temperature in the vault down to about -25°F. The cooling systems then give nature a mechanical boost to keep the seed vault chilled even further, to about -64°F, the optimal temperature for conserving seeds. In addition to upgrading to a more effective and sustainable cooling system that runs on CO2, the Norwegian government added backup generators, removed heat-generating electrical equipment from inside the facility to an outside building, installed a thick, watertight door to the vault, and replaced the corrugated steel access tunnel with a cement tunnel that uses the same waterproofing technology as the North Sea oil platforms.

To re-establish the permafrost around the tunnel, they layered cooling pipes with frozen soil around the concrete tunnel, covered the frozen soil with a cooling mat, and topped the cooling mat with the original permafrost soil. They also added drainage ditches on the mountainside to divert meltwater away from the tunnel as the climate gets warmer and wetter.

New Deposits to the Global Vault

The day before COVID-19 arrived in Norway, on February 25th, Prime Minister Erna Solberg hosted the biggest seed-depositing event in the vault's history in honor of the new and improved vault. As snow fell on Svalbard, depositors from almost every continent traveled the windy road from Longyearbyen up Platåfjellet Mountain and braved frigid -8°F weather to celebrate the massive technical upgrades to the facility – and to hand over their seeds.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization, and Israel's University of Haifa, whose deposit included multiple genotypes of wild emmer wheat, an ancient relative of the modern domesticated crop. The storage boxes carried ceremoniously over the threshold that day contained more than 65,000 new seed samples, bringing the total to more than a million, and almost filling the first of three seed chambers in the vault. (The Global Vault can store up to 4.5 million seed samples.)

"Svalbard's samples contain all the possibilities, all the options for the future of our agricultural crops – it's how crops are going to adapt," says Cary Fowler, former executive director of the Crop Trust, who was instrumental in establishing the Global Vault. "If our crops don't adapt to climate change, then neither will we." Dr. Fowler says he is confident that with the recent improvements in the vault, the seeds are going to remain viable for a very long time.

"It's sometimes tempting to get distracted by the romanticism of a seed vault inside a mountain near the North Pole – it's a little bit James Bondish," muses Dr. Fowler. "But the reality is we've essentially put an end to the extinction of more than a million samples of biodiversity forever."