How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

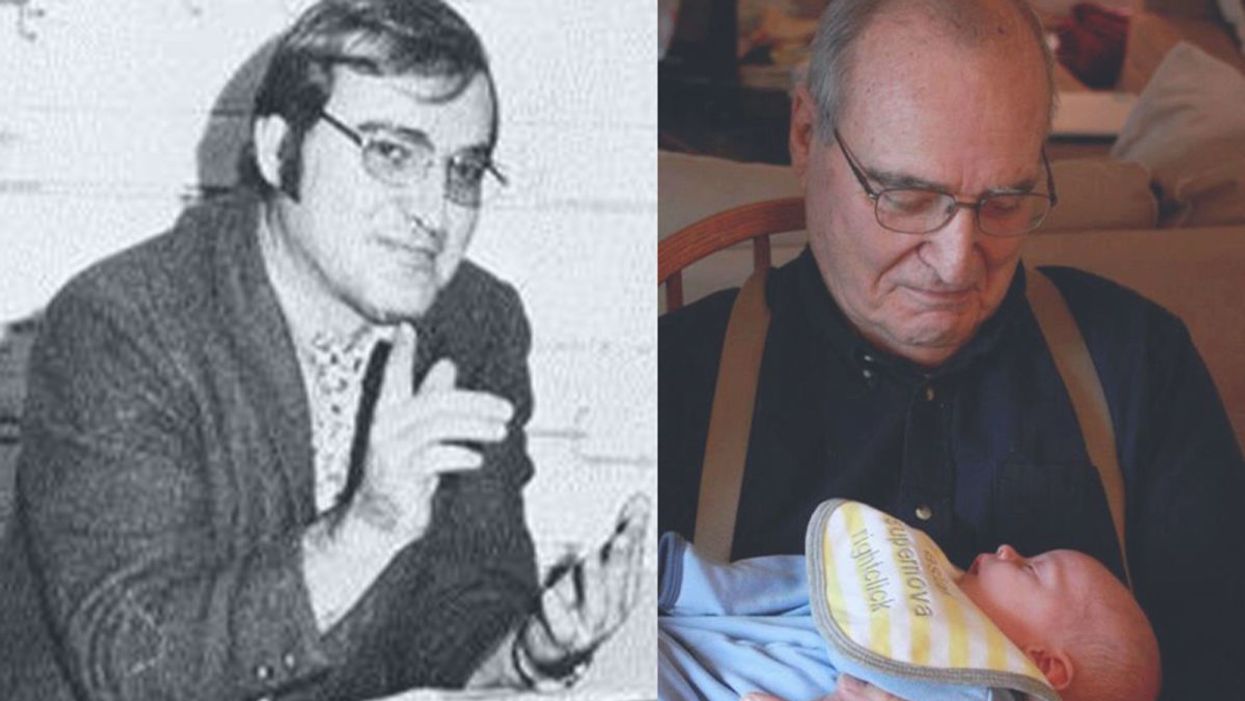

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

Will the Pandemic Propel STEM Experts to Political Power?

The White House rising out of a Petri dish.

If your car won't run, you head to a mechanic. If your faucet leaks, you contact a plumber. But what do you do if your politics are broken? You call a… lawyer.

"Scientists have been more engaged with politics over the past three years amid a consistent sidelining of science and expertise, and now the pandemic has crystalized things even more."

That's been the American way since the beginning. Thousands of members of the House and Senate have been attorneys, along with nearly two dozen U.S. presidents from John Adams to Abraham Lincoln to Barack Obama. But a band of STEM professionals is changing the equation. They're hoping anger over the coronavirus pandemic will turn their expertise into a political superpower that propels more of them into office.

"This could be a turning point, part of an acceleration of something that's already happening," said Nancy Goroff, a New York chemistry professor who's running for a House seat in Long Island and will apparently be the first female scientist with a Ph.D. in Congress. "Scientists have been more engaged with politics over the past three years amid a consistent sidelining of science and expertise, and now the pandemic has crystalized things even more."

Professionals in the science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM) fields don't have an easy task, however. To succeed, they must find ways to engage with voters instead of their usual target audiences — colleagues, patients and students. And they'll need to beat back a long-standing political tradition that has made federal and state politics a domain of attorneys and businesspeople, not nurses and biologists.

In the 2017-2018 Congress, more members of Congress said they'd worked as radio talk show hosts (seven) and as car dealership owners (six) than scientists (three — a physicist, a microbiologist, and a chemist), according to a 2018 report from the Congressional Research Service. There were more bankers (18) than physicians (14), more management consultants (18) than engineers (11), and more former judges (15) than dentists (4), nurses (2), veterinarians (3), pharmacists (1) and psychologists (3) combined.

In 2018, a "STEM wave" brought nine members with STEM backgrounds into office. But those with initials like PhD, MD and RN after their names are still far outnumbered by Esq. and MBA types.

Why the gap? Astrophysicist Rush Holt Jr., who served from 1999-2015 as a House representative from New Jersey, thinks he knows. "I have this very strong belief, based on 16 years in Congress and a long, intense public life, that the problem is not with science or the scientists," said. "It has to do with the fact that the public just doesn't pay attention to science. It never occurs to them that they have any role in the matter."

But Holt, former chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, believes change is on the way. "It's likely that the pandemic will affect people's attitudes," former congressman Holt said, "and lead them to think that they need more scientific thinking in policy-making and legislating." Holt's father was a U.S. senator from West Virginia, so he grew up with a political education. But how can scientists and medical professionals succeed if they have no background in the art of wooing voters?

That's where an organization called 314 Action comes in. Named after the first three digits of pi, 314 Action declares itself to be the "pro-science resistance" and says it's trained more than 1,400 scientists to run for public office.

In 2018, 9 out of 13 House and Senate candidates endorsed by the group won their races. In 2020, 314 Action is endorsing 12 candidates for the House (including an engineer), four for the Senate (including an astronaut) and one for governor (a mathematician in Kansas). It expects to spend $10 million-$20 million to support campaigns this year.

"Physicians, scientists and engineers are problem-solvers," said Shaughnessy Naughton, a Pennsylvania chemist who founded 314 Action after an unsuccessful bid for Congress. "They're willing to dive into issues, and their skills would benefit policy decisions that extend way beyond their scientific fields of expertise."

Like many political organizations, 314 Action focuses on teaching potential candidate how to make it in politics, aiming to help them drop habits that fail to bridge the gap between scientists and civilians. "Their first impulse is not to tell a story," public speaking coach Chris Jahnke told the public radio show "Marketplace" in 2018. "They would rather start with a stat." In a training session, Jahnke aimed to teach them to do both effectively.

"It just comes down to being able to speak about general principles in regular English, and to always have the science intertwined with basic human values," said Rep. Kim Schrier, a Washington state pediatrician who won election to Congress in 2018.

She believes her experience on the job has helped her make connections with voters. In a chat with parents about vaccines for their child, for example, she knows not to directly jump into an arcane discussion of case-control studies.

The best alternative, she said, is to "talk about how hard it is to be a parent making these decisions, feeling scared and worried. Then say that you've looked at the data and the research, and point out that pediatricians would never do anything to hurt children because we want to do everything that is good for them. When you speak heart to heart, it gets across the message and the credibility of medicine and science."

The pandemic "will hopefully awaken people and trigger a change that puts science, medicine and public health on a pedestal where science is revered and not dismissed as elitist."

Communication skills will be especially important if the pandemic spurs more Americans to focus on politics and the records of incumbents in regard to matters like public health and climate change. Thousands of candidates will have to address the nation's coronavirus response, and a survey commissioned by 314 Action suggests that voters may be receptive to those with STEM backgrounds. The poll, of 1,002 likely voters in early April 2020, found that 41%-46% of those surveyed said they'd be "much more favorable" toward candidates who were doctors, nurses, scientists and public health professionals. Those numbers were the highest in the survey compared to just 9% for lawyers.

The pandemic "will hopefully awaken people and trigger a change that puts science, medicine and public health on a pedestal where science is revered and not dismissed as elitist," Dr. Schrier said. "It will come from a recognition that what's going to get us out of this bind are scientists, vaccine development and the hard work of the people in public health on the ground."

[This article was originally published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]

While lab-grown meat is not yet ready to crisis-proof the food supply chain, it offers key benefits that could make it an important solution beyond this pandemic.

The coronavirus pandemic exposed significant weaknesses in the country's food supply chain. Grocery store meat counters were bare. Transportation interruptions influenced supply. Finding beef, poultry, and pork at the store has been, in some places, as challenging as finding toilet paper.

In traditional agriculture models, it takes at least three months to raise chicken, six to nine months for pigs, and 18 months for cattle.

It wasn't a lack of supply -- millions of animals were in the pipeline.

"There's certainly enough food out there, but it can't get anywhere because of the way our system is set up," said Amy Rowat, an associate professor of integrative biology and physiology at UCLA. "Having a more self-contained, self-sufficient way to produce meat could make the supply chain more robust."

Cultured meat could be one way of making the meat supply chain more resilient despite disruptions due to pandemics such as COVID-19. But is the country ready to embrace lab-grown food?

According to a Good Food Institute study, GenZ is almost twice as likely to embrace meat alternatives for reasons related to social and environmental awareness, even prior to the pandemic. That's because this group wants food choices that reflect their values around food justice, equity, and animal welfare.

Largely, the interest in protein alternatives has been plant-based foods. However, factors directly related to COVID-19 may accelerate consumer interest in the scaling up of cell-grown products, according to Liz Specht, the associate director of science and technology at The Good Food Institute. The latter is a nonprofit organization that supports scientists, investors, and entrepreneurs working to develop food alternatives to conventional animal products.

While lab-grown food isn't ready yet to definitively crisis-proof the food supply chain, experts say it offers promise.

Matching Supply and Demand

Companies developing cell-grown meat claim it can take as few as two months to develop a cell into an edible product, according to Anthony Chow, CFA at Agronomics Limited, an investment company focused on meat alternatives. Tissue is taken from an animal and placed in a culture that contains nutrients and proteins the cells need to grow and expand. He cites a Good Food Institute report that claims a 2.5-millimeter sample can grow three and a half tons of meat in 40 days, allowing for exponential growth when needed.

In traditional agriculture models, it takes at least three months to raise chicken, six to nine months for pigs, and 18 months for cattle. To keep enough maturing animals in the pipeline, farms must plan the number of animals to raise months -- even years -- in advance. Lab-grown meat advocates say that because cultured meat supplies can be flexible, it theoretically allows for scaling up or down in significantly less time.

"Supply and demand has drastically changed in some way around the world and cultivated meat processing would be able to adapt much quicker than conventional farming," Chow said.

Scaling Up

Lab-grown meat may provide an eventual solution, but not in the immediate future, said Paul Mozdziak, a professor of physiology at North Carolina State University who researches animal cell culture techniques, transgenic animal production, and muscle biology.

"The challenge is in culture media," he said. "It's going to take some innovation to get the cells to grow at quantities that are going to be similar to what you can get from an animal. These are questions that everybody in the space is working on."

Chow says some of the most advanced cultured meat companies, such as BlueNal, anticipate introducing products to the market midway through next year. However, he thinks COVID-19 has slowed the process. Once introduced, they will be at a premium price, most likely available at restaurants before they hit grocery store shelves.

"I think in five years' time it will be in a different place," he said. "I don't think that this will have relevance for this pandemic, but certainly beyond that."

"Plant-based meats may be perceived as 'alternatives' to meat, whereas lab-grown meat is producing the same meat, just in a much more efficient manner, without the environmental implications."

Of course, all the technological solutions in the world won't solve the problem unless people are open-minded about embracing them. At least for now, a lab-grown burger or bluefin tuna might still be too strange for many people, especially in the U.S.

For instance, a 2019 article published by "Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems" reflects results from a study of 3,030 consumers showing that 29 percent of U.S. customers, 59 percent of Chinese consumers, and 56 percent of Indian consumers were either 'very' or 'extremely likely' to try cultivated meat.

"Lab-grown meat is genuine meat, at the cellular level, and therefore will match conventional meat with regard to its nutritional content and overall sensory experience. It could be argued that plant-based meat will never be able to achieve this," says Laura Turner, who works with Chow at Agronomics Limited. "Plant-based meats may be perceived as 'alternatives' to meat, whereas lab-grown meat is producing the same meat, just in a much more efficient manner, without the environmental implications."

A Solution Beyond This Pandemic

The coronavirus has done more than raise awareness of the fragility of food supply chains. It has also been a wakeup call for consumers and policy makers that it is time to radically rethink our meat, Specht says. Those factors have elevated the profile of lab-grown meat.

"I think the economy is getting a little bit more steam and if I was an investor, I would be getting excited about it," adds Mozdziak.

Beyond crises, Mozdziak explains that as affluence continues to increase globally, meat consumption increases exponentially. Yet farm animals can only grow so quickly and traditional farming won't be able to keep up.

"Even Tyson is saying that by 2050, there's not going to be enough capacity in the animal meat space to meet demand," he notes. "If we don't look at some innovative technologies, how are we going to overcome that?"