How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

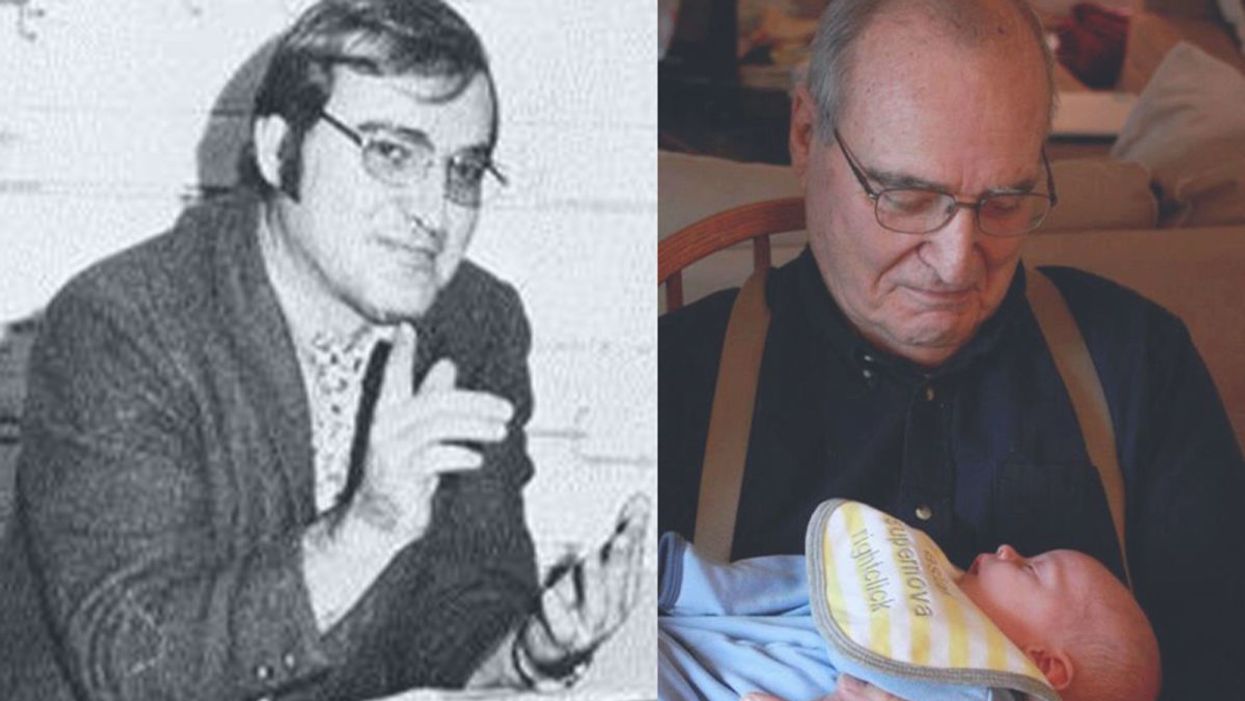

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

We Pioneered a Technology to Save Millions of Poor Children, But a Worldwide Smear Campaign Has Blocked It

On left, a picture of white rice next to Golden Rice, and on right, a girl who lost one eye due to vitamin A deficiency.

In a few weeks it will be 20 years that we three have been working together. Our project has been independently praised as one of the most influential of all projects of the last 50 years.

Two of us figured out how to make rice produce a source of vitamin A, and the rice becomes a golden color instead of white.

The project's objectives have been admired by some and vilified by others. It has directly involved teams of highly motivated people from a handful of nations, from both the private and public sector. A book, dedicated to the three of us, has been written about our work. Nevertheless, success has, so far, eluded us all. The story of our thwarted efforts is a tragedy that we hope will soon – finally – reach a milestone of potentially profound significance for humanity.

So, what have we been working on, and why haven't we succeeded yet?

Food: everybody needs it, and many are fortunate enough to have enough, even too much of it. Food is a highly emotional subject on every continent and in every culture. For a healthy life our food has to provide energy, as well as, in very small amounts, minerals and vitamins. A varied diet, easily achieved and common in industrialised countries, provides everything.

But poor people in countries where rice is grown often eat little else. White rice only provides energy: no minerals or vitamins. And the lack of one of the vitamins, vitamin A, is responsible for killing around 4,500 poor children every day. Lack of vitamin A is the biggest killer of children, and also the main cause of irreversible childhood blindness.

Our project is about fixing this one dietary deficiency – vitamin A – in this one crop – rice – for this one group of people. It is a huge group though: half of the world's population live by eating a lot of rice every day. Two of us (PB & IP) figured out how to make rice produce a source of vitamin A, and the rice becomes a golden color instead of white. The source is beta-carotene, which the human body converts to vitamin A. Beta-carotene is what makes carrots orange. Our rice is called "Golden Rice."

The technology has been donated to assist those rice eaters who suffer from vitamin A deficiency ('VAD') so that Golden Rice will cost no more than white rice, there will be no restrictions on the small farmers who grow it, and nothing extra to pay for the additional nutrition. Very small amounts of beta-carotene will contribute to alleviation of VAD, and even the earliest version of Golden Rice – which had smaller amounts than today's Golden Rice - would have helped. So far, though, no small farmer has been allowed to grow it. What happened?

To create Golden Rice, it was necessary to precisely add two genes to the 30,000 genes normally present in rice plants. One of the genes is from maize, also known as corn, and the other from a commonly eaten soil bacterium. The only difference from white rice is that Golden Rice contains beta-carotene.

It has been proven to be safe to man and the environment, and consumption of only small quantities of Golden Rice will combat VAD, with no chance of overdosing. All current Golden Rice results from one introduction of these two genes in 2004. But the use of that method – once, 15 years ago - means that Golden Rice is a 'GMO' ('genetically modified organism'). The enzymes used in the manufacture of bread, cheese, beer and wine, and the insulin which diabetics take to keep them alive, are all made from GMOs too.

The first GMO crops were created by agri-business companies. Suspicion of the technology and suspicion of commercial motivations merged, only for crop (but not enzymes or pharmaceutical) applications of GMO technology. Activists motivated by these suspicions were successful in getting the 'precautionary principle' incorporated in an international treaty which has been ratified by 166 countries and the European Union – The Cartagena Protocol.

The equivalent of 13 jumbo jets full of children crashes into the ground every day and kills them all, because of vitamin A deficiency.

This protocol is the basis of national rules governing the introduction of GMO crops in every signatory country. Government regulators in, and for, each country must agree before a GMO crop can be 'registered' to be allowed to be used by the public in that country. Currently regulatory decisions to allow Golden Rice release are being considered in Bangladesh and the Philippines.

The Cartagena Protocol obliges the regulators in each country to consider all possible risks, and to take no account of any possible benefits. Because the anti-gmo-activists' initial concerns were principally about the environment, the responsibility for governments' regulation for GMO crops – even for Golden Rice, a public health project delivered through agriculture – usually rests with the Ministry of the Environment, not the Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Agriculture.

Activists discovered, before Golden Rice was created, that inducing fear of GMO food crops from 'multinational agribusinesses' was very good for generating donations from a public that was largely illiterate about food technology and production. And this source of emotionally charged donations would cease if Golden Rice was proven to save sight and lives, because Golden Rice represented the opposite of all the tropes used in anti-GMO campaigns.

Golden Rice is created to deliver a consumer benefit, it is not for profit – to multinational agribusiness or anyone else; the technology originated in the public sector and is being delivered through the public sector. It is entirely altruistic in its motivations; which activists find impossible to accept. So, the activists believed, suspicion against Golden Rice had to be amplified, Golden Rice had to be stopped: "If we lose the Golden Rice battle, we lose the GMO war."

Activism continues to this day. And any Environment Ministry, with no responsibility for public health or agriculture, and of course an interest in avoiding controversy about its regulatory decisions, is vulnerable to such activism.

The anti-GMO crop campaigns, and especially anti-Golden Rice campaigns, have been extraordinarily effective. If so much regulation by governments is required, surely there must be something to be suspicious about: 'There is no smoke without fire'. The suspicion pervades research institutions and universities, the publishers of scientific journals and The World Health Organisation, and UNICEF: even the most scientifically literate are fearful of entanglement in activist-stoked public controversy.

The equivalent of 13 jumbo jets full of children crashes into the ground every day and kills them all, because of VAD. Yet the solution of Golden Rice, developed by national scientists in the counties where VAD is endemic, is ignored because of fear of controversy, and because poor children's deaths can be ignored without controversy.

Perhaps more controversy lies in not taking scientifically based regulatory decisions than in taking them.

The tide is turning, however. 151 Nobel Laureates, a very significant proportion of all Nobel Laureates, have called on the UN, governments of the world, and Greenpeace to cease their unfounded vilification of GMO crops in general and Golden Rice in particular. A recent Golden Rice article commented, "What shocks me is that some activists continue to misrepresent the truth about the rice. The cynic in me expects profit-driven multinationals to behave unethically, but I want to think that those voluntarily campaigning on issues they care about have higher standards."

The recently published book has exposed the frustrating saga in simple detail. And the publicity from all the above is perhaps starting to change the balance of where controversy lies. Perhaps more controversy lies in not taking scientifically based regulatory decisions than in taking them.

But until they are taken, while there continues a chance of frustrating the objectives of the Golden Rice project, the antagonism will continue. And despite a solution so close at hand, VAD-induced death and blindness, and the misery of affected families, will continue also.

© The Authors 2019. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

An emerging technology called in vitro gametogenesis would allow babies to be made from skin cells.

[Ed. Note: This is the third episode in our Moonshot series, which will explore four cutting-edge scientific developments that stand to fundamentally transform our world.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.