How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

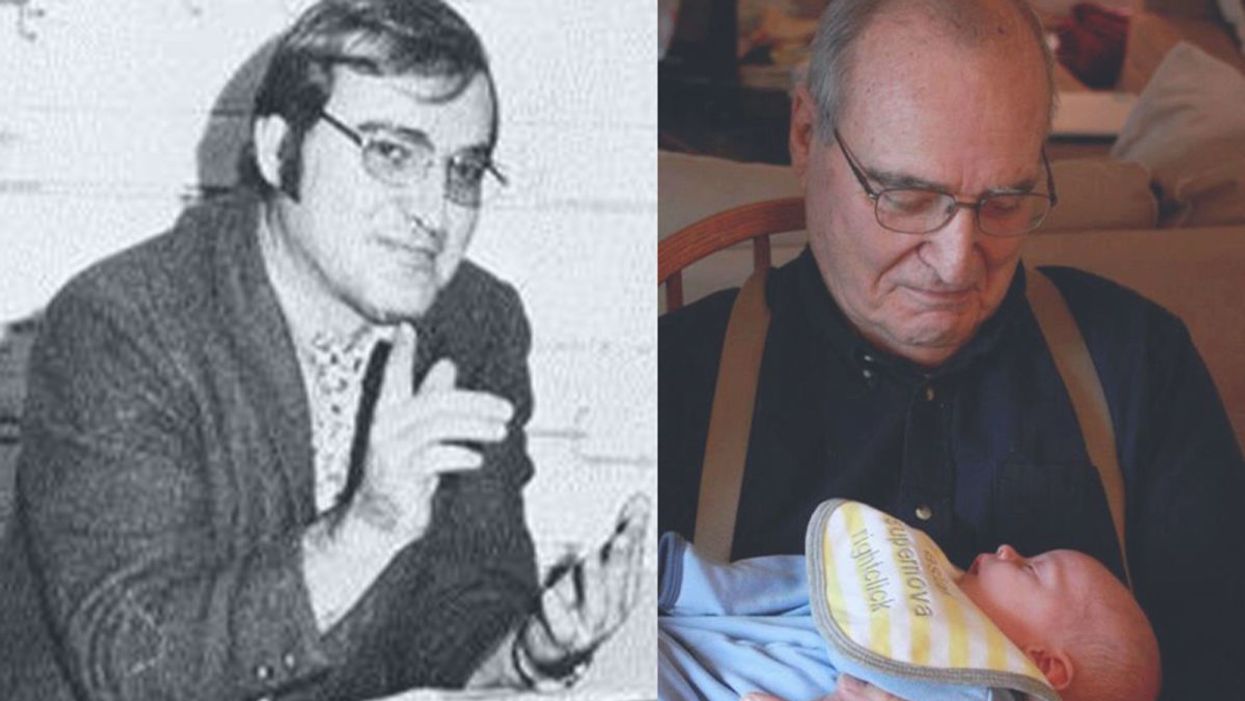

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

Your Body Has This Astonishing Magical Power

A fierce champion fighter in action, representing the incredible power of the human immune system.

It's vacation time. You and your family visit a country where you've never been and, in fact, your parents or grandparents had never been. You find yourself hiking beside a beautiful lake. It's a gorgeous day. You dive in. You are not alone.

How can your T cells and B cells react to a pathogen they've never seen?

In the water swim parasites, perhaps a parasite called giardia. The invader slips in through your mouth or your urinary tract. This bug is entirely new to you, and there's more. It might be new to everyone you've ever met or come into contact with. The parasite may have evolved in this setting for hundreds of thousands of years so that it's different from any giardia bug you've ever come into contact with before or that thrives in the region where you live.

How can your T cells and B cells react to a pathogen they've never seen, never knew existed, and were never inoculated against, and that you, or your doctors, in all their wisdom, could never have foreseen?

This is the infinity problem.

For years, this was the greatest mystery in immunology.

As I reported An Elegant Defense -- my book about the science of the immune system told through the lives of scientists and medical patients -- I was repeatedly struck by the profundity of this question. It is hard to overstate: how can we survive in a world with such myriad possible threats?

Matt Richtel's new book about the science of the immune system, An Elegant Defense, was published this month.

To further underscore the quandary, the immune system has to neutralize threats without killing the rest of the body. If the immune system could just kill the rest of the body too, the solution to the problem would be easy. Nuke the whole party. That obviously won't work if we are to survive. So the immune system has to be specific to the threat while also leaving most of our organism largely alone.

"God had two options," Dr. Mark Brunvand told me. "He could turn us into ten-foot-tall pimples, or he could give us the power to fight 10 to the 12th power different pathogens." That's a trillion potential bad actors. Why pimples? Pimples are filled with white blood cells, which are rich with immune system cells. In short, you could be a gigantic immune system and nothing else, or you could have some kind of secret power that allowed you to have all the other attributes of a human being—brain, heart, organs, limbs—and still somehow magically be able to fight infinite pathogens.

Dr. Brunvand is a retired Denver oncologist, one of the many medical authorities in the book – from wizened T-cell innovator Dr. Jacques Miller, to the finder of fever, Dr. Charles Dinarello, to his eminence Dr. Anthony Fauci at the National Institutes of Health to newly minted Nobel-Prize winner Jim Allison.

In the case of Dr. Brunvand, the oncologist also is integral to one of the book's narratives, a remarkable story of a friend of mine named Jason. Four years ago, he suffered late, late stage cancer, with 15 pounds of lymphoma growing in his back, and his oncologist put him into hospice. Then Jason became one of the first people ever to take an immunotherapy drug for lymphoma and his tumors disappeared. Through Jason's story, and a handful of other fascinating tales, I showcase how the immune system works.

There are two options for creating such a powerful immune system: we could be pimples or have some other magical power.

Dr. Brunvand had posited to me that there were two options for creating such a powerful and multifaceted immune system: we could be pimples or have some other magical power. You're not a pimple. So what was the ultimate solution?

Over the years, there were a handful of well-intentioned, thoughtful theories, but they strained to account for the inexplicable ability of the body to respond to virtually anything. The theories were complex and suffered from that peculiar side effect of having terrible names—like "side-chain theory" and "template-instructive hypothesis."

This was the background when along came Susumu Tonegawa.

***

Tonegawa was born in 1939, in the Japanese port city of Nagoya, and was reared during the war. Lucky for him, his father was moved around in his job, and so Tonegawa grew up in smaller towns. Otherwise, he might've been in Nagoya on May 14,1944, when the United States sent nearly 550 B-29 bombers to take out key industrial sites there and destroyed huge swaths of the city.

Fifteen years later, in 1959, Tonegawa was a promising student when a professor in Kyoto told him that he should go to the United States because Japan lacked adequate graduate training in molecular biology. A clear, noteworthy phenomenon was taking shape: Immunology and its greatest discoveries were an international affair, discoveries made through cooperation among the world's best brains, national boundaries be damned.

Tonegawa wound up at the University of California at San Diego, at a lab in La Jolla, "the beautiful Southern California town near the Mexican border." There, in multicultural paradise, he received his PhD, studying in the lab of Masaki Hayashi and then moved to the lab of Renato Dulbecco. Dr. Dulbecco was born in Italy, got a medical degree, was recruited to serve in World War II, where he fought the French and then, when Italian fascism collapsed, joined the resistance and fought the Germans. (Eventually, he came to the United States and in 1975 won a Nobel Prize for using molecular biology to show how viruses can lead, in some cases, to tumor creation.)

In 1970, Tonegawa—now armed with a PhD—faced his own immigration conundrum. His visa was set to expire by the end of 1970, and he was forced to leave the country for two years before he could return. He found a job in Switzerland at the Basel Institute for Immunology.

***

Around this time, new technology had emerged that allowed scientists to isolate different segments of an organism's genetic material. The technology allowed segments to be "cut" and then compared to one another. A truism emerged: If a researcher took one organism's genome and cut precisely the same segment over and over again, the resulting fragment of genetic material would match each time.

When you jump in that lake in a foreign land, filled with alien bugs, your body, astonishingly, well might have a defender that recognizes the creature.

This might sound obvious, but it was key to defining the consistency of an organism's genetic structure.

Then Tonegawa found the anomaly.

He was cutting segments of genetic material from within B cells. He began by comparing the segments from immature B cells, meaning, immune system cells that were still developing. When he compared identical segments in these cells, they yielded, predictably, identical fragments of genetic material. That was consistent with all previous knowledge.

But when he compared the segments to identical regions in mature B cells, the result was entirely different. This was new, distinct from any other cell or organism that had been studied. The underlying genetic material had changed.

"It was a big revelation," said Ruslan Medzhitov, a Yale scholar. "What he found, and is currently known, is that the antibody-encoding genes are unlike all other normal genes."

The antibody-encoding genes are unlike all other normal genes.

Yes, I used italics. Your immune system's incredible capabilities begin from a remarkable twist of genetics. When your immune system takes shape, it scrambles itself into millions of different combinations, random mixtures and blends. It is a kind of genetic Big Bang that creates inside your body all kinds of defenders aimed at recognizing all kinds of alien life forms.

So when you jump in that lake in a foreign land, filled with alien bugs, your body, astonishingly, well might have a defender that recognizes the creature.

Light the fireworks and send down the streamers!

As Tonegawa explored further, he discovered a pattern that described the differences between immature B cells and mature ones. Each of them shared key genetic material with one major variance: In the immature B cell, that crucial genetic material was mixed in with, and separated by, a whole array of other genetic material.

As the B cell matured into a fully functioning immune system cell, much of the genetic material dropped out. And not just that: In each maturing B cell, different material dropped out. What had begun as a vast array of genetic coding sharpened into this particular, even unique, strand of genetic material.

***

This is complex stuff. But a pep talk: This section is as deep and important as any in describing the wonder of the human body. Dear reader, please soldier on!

***

Researchers, who, eventually, sought a handy way to define the nature of the genetic change to the material of genes, labeled the key genetic material in an antibody with three initials: V, D, and J.

The letter V stands for variable. The variable part of the genetic material is drawn from hundreds of genes.

D stands for diversity, which is drawn from a pool of dozens of different genes.

And J is drawn from another half dozen genes.

In an immature B cell, the strands of V, D, and J material are in separate groupings, and they are separated by a relatively massive distance. But as the cell matures, a single, random copy of V remains, along with a single each of D and J, and all the other intervening material drops out. As I began to grasp this, it helped me to picture a line of genetic material stretching many miles. Suddenly, three random pieces step forward, and the rest drops away.

The combination of these genetic slices, grouped and condensed into a single cell, creates, by the power of math, trillions of different and virtually unique genetic codes.

In anticipation of threats from the unfathomable, our defenses evolved as infinity machines.

Or if you prefer a different metaphor, the body has randomly made hundreds of millions of different keys, or antibodies. Each fits a lock that is located on a pathogen. Many of these antibodies are combined such that they are alien genetic material—at least to us—and their locks will never surface in the human body. Some may not exist in the entire universe. Our bodies have come stocked with keys to the rarest and even unimaginable locks, forms of evil the world has not yet seen, but someday might. In anticipation of threats from the unfathomable, our defenses evolved as infinity machines.

"The discoveries of Tonegawa explain the genetic background allowing the enormous richness of variation among antibodies," the Nobel Prize committee wrote in its award to him years later, in 1987. "Beyond deeper knowledge of the basic structure of the immune system these discoveries will have importance in improving immunological therapy of different kinds, such as, for instance, the enforcement of vaccinations and inhibition of reactions during transplantation. Another area of importance is those diseases where the immune defense of the individual now attacks the body's own tissues, the so-called autoimmune diseases."

Indeed, these revelations are part of a period of time it would be fair to call the era of immunology, stretching from the middle of the 20th century to the present. During that period, we've come from sheer ignorance of the most basic aspects of the immune system to now being able to tinker under the hood with monoclonal antibodies and other therapies. And we are, in many ways, just at the beginning.

Scientists and Religious Leaders Need to Be More Transparent

A steeple cross at sunset.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question series: "How can the religious and scientific communities work together to foster a culture that is equipped to face humanity's biggest challenges?"]

As a Jesuit Catholic priest, and a molecular geneticist, this question has been a fundamental part of my adult life. But first, let me address an issue that our American culture continues to struggle with: how do science and religion actually relate to each other? Is science about the "real" world, and religion just about individual or group beliefs about how the world should be?

Or are science and religion in direct competition with both trying to construct explanations of reality that are "better" or more real than the other's approach? These questions have generated much discussion among scientists, philosophers, and theologians.

The recent advances in our understanding of genetics show how combining the insights of science and religion can be beneficial.

First, we need to be clear that science and religion are two different ways human beings use to understand reality. Science focuses on observable, quantifiable, physical aspects of our universe, whereas, religion, while taking physical reality into consideration, also includes the immaterial, non-quantifiable, human experiences and concepts which relate to the meaning and purpose of existence. While scientific discoveries also often stimulate such profound reflections, these reflections are not technically a part of scientific methodology.

Second, though different in both method and focus, neither way of understanding reality produces a more "real" or accurate comprehension of our human existence. In fact, most often both science and religion add valuable insights into any particular situation, providing a more complete understanding of it as well as how it might be improved.

The recent advances in our understanding of genetics show how combining the insights of science and religion can be beneficial. For instance, the study of genetic differences among people around the world has shown us that the idea that we could accurately classify people as belonging to different races—e.g. African, Caucasian, Asian, etc.—is actually quite incorrect on a biological level. In fact, in many ways two people who appear to be of different races, perhaps African and Caucasian, could be more similar genetically than two people who appear to be of the same African race.

This scientific finding, then, challenges us to critically review the social categories some use to classify people as different from us, and, therefore, somehow of less worth to society. From this perspective, one could argue that this scientific insight synergizes well with some common fundamental religious beliefs regarding the fundamental equality all people have in their relationship to the Divine.

However, this synergy between science and religion is not what we encounter most often in the mass media or public policy debates. In part, this is due to the fact that science and religion working well together is not normally considered newsworthy. What does get attention is when science appears to conflict with religion, or, perhaps more accurately, when the scientific community conflicts with religious communities regarding how a particular scientific advance should be applied. These disagreements usually are not due to a conflict between scientific findings and religious beliefs, but rather between differing moral, social or political agendas.

One way that the two sides can work together is to prioritize honesty and accuracy in public debates instead of crafting informational campaigns to promote political advantage.

For example, genetically modified foods have been a source of controversy for the past several decades. While the various techniques used to create targeted genetic changes in plants—e.g. drought or pest resistance—are scientifically intricate and complex, explaining these techniques to the public is similar to explaining complex medical treatments to patients. Hence, the science alone is not the issue.

The controversy arises from the differing goals various stakeholders have for this technology. Obviously, companies employing this technology want it to be used around the world both for its significantly improved food production, and for improved revenue. Opponents, which have included religious communities, focus more on the social and cultural disruption this technology can create. Since a public debate between a complex technology on one side, and a complex social situation on the other side, is difficult to undertake well, the controversy has too often been reduced to sound bites such as "Frankenfoods." While such phrases may be an effective way to influence public opinion, ultimately, they work against sensible decision-making.

One way that the two sides can work together is to prioritize honesty and accuracy in public debates instead of crafting informational campaigns to promote political advantage. I recognize that presenting a thorough and honest explanation of an organization's position does not fit easily into our 24-hour-a-day-sound-bite system, but this is necessary to make the best decisions we can if we want to foster a healthier and happier world.

Climate change and human genome editing are good examples of this problem. These are both complex issues with impacts that extend well beyond just science and religious beliefs—including economics, societal disruption, and an exacerbation of social inequalities. To achieve solutions that result in significant benefits for the vast majority of people, we must work to create a knowledgeable public that is encouraged to consider the good of both one's own community as well as that of all others. This goal is actually one that both scientific and religious organizations claim to value and pursue.

The experts often fail to understand sufficiently what the public hopes, wants, and fears.

Unfortunately, both types of organizations often fall short because they focus only on informing and instructing instead of truly engaging the public in deliberation. Often both scientists and religious leaders believe that the public is not capable of sufficiently understanding the complexities of the issues, so they resort to assuming that the public should just do what the experts tell them.

However, there is significant research that demonstrates the ability of the general public to grasp complex issues in order to make sound decisions. Hence, it is the experts who often fail to understand how their messages are being received and what the public hopes, wants, and fears.

Overall, I remain sanguine about the likelihood of both religious and scientific organizations learning how to work better with each other, and together with the public. Working together for the good of all, we can integrate the insights and the desires of all stakeholders in order to face our challenges with well-informed reason and compassion for all, particularly those most in need.

[Ed. Note: Don't miss the other perspectives in this Big Question series, from a science scholar and a Rabbi/M.D.]