How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

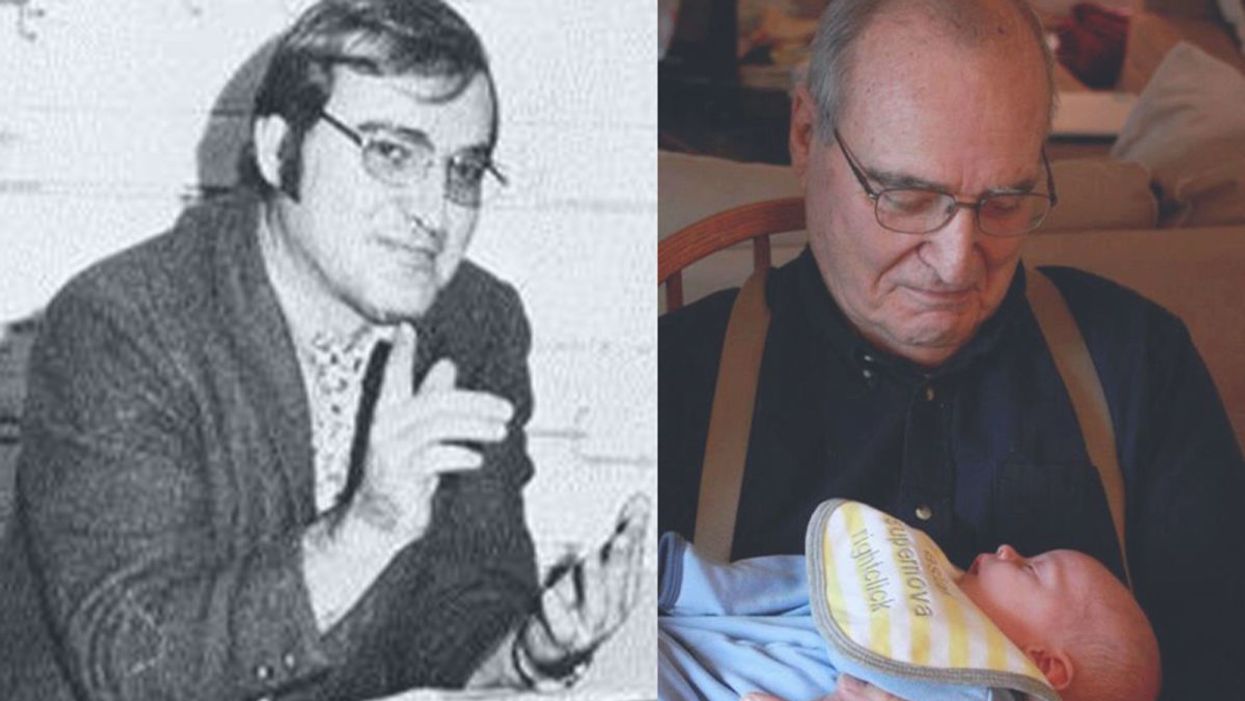

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

“Young Blood” Transfusions Are Not Ready For Primetime – Yet

A young woman donates blood.

The world of dementia research erupted into cheers when news of the first real victory in a clinical trial against Alzheimer's Disease in over a decade was revealed last October.

By connecting the circulatory systems of a young and an old mouse, the regenerative potential of the young mouse decreased, and the old mouse became healthier.

Alzheimer's treatments have been famously difficult to develop; 99 percent of the 200-plus such clinical trials since 2000 have utterly failed. Even the few slight successes have failed to produce what is called 'disease modifying' agents that really help people with the disease. This makes the success, by the midsize Spanish pharma company Grifols, worthy of special attention.

However, the specifics of the Grifols treatment, a process called plasmapheresis, are atypical for another reason - they did not give patients a small molecule or an elaborate gene therapy, but rather simply the most common component of normal human blood plasma, a protein called albumin. A large portion of the patients' normal plasma was removed, and then a sterile solution of albumin was infused back into them to keep their overall blood volume relatively constant.

So why does replacing Alzheimer's patients' plasma with albumin seem to help their brains? One theory is that the action is direct. Alzheimer's patients have low levels of serum albumin, which is needed to clear out the plaques of amyloid that slowly build up in the brain. Supplementing those patients with extra albumin boosts their ability to clear the plaques and improves brain health. However, there is also evidence suggesting that the problem may be something present in the plasma of the sick person and pulling their plasma out and replacing it with a filler, like an albumin solution, may be what creates the purported benefit.

This scientific question is the tip of an iceberg that goes far beyond Alzheimer's Disease and albumin, to a debate that has been waged on the pages of scientific journals about the secrets of using young, healthy blood to extend youth and health.

This debate started long before the Grifols data was released, in 2014 when a group of researchers at Stanford found that by connecting the circulatory systems of a young and an old mouse, the regenerative potential of the young mouse decreased, and the old mouse became healthier. There was something either present in young blood that allowed tissues to regenerate, or something present in old blood that prevented regeneration. Whatever the biological reason, the effects in the experiment were extraordinary, providing a startling boost in health in the older mouse.

After the initial findings, multiple research groups got to work trying to identify the "active factor" of regeneration (or the inhibitor of that regeneration). They soon uncovered a variety of compounds such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), CCL11, and GDF11, but none seemed to provide all the answers researchers were hoping for, with a number of high-profile retractions based on unsound experimental practices, or inconclusive data.

Years of research later, the simplest conclusion is that the story of plasma regeneration is not simple - there isn't a switch in our blood we can flip to turn back our biological clocks. That said, these hypotheses are far from dead, and many researchers continue to explore the possibility of using the rejuvenating ability of youthful plasma to treat a variety of diseases of aging.

But the bold claims of improved vigor thanks to young blood are so far unsupported by clinical evidence.

The data remain intriguing because of the astounding results from the conjoined circulatory system experiments. The current surge in interest in studying the biology of aging is likely to produce a new crop of interesting results in the next few years. Both CCL11 and GDF11 are being researched as potential drug targets by two startups, Alkahest and Elevian, respectively.

Without clarity on a single active factor driving rejuvenation, it's tempting to try a simpler approach: taking actual blood plasma provided by young people and infusing it into elderly subjects. This is what at least one startup company, Ambrosia, is now offering in five commercial clinics across the U.S. -- for $8,000 a liter.

By using whole plasma, the idea is to sidestep our ignorance, reaping the benefits of young plasma transfusion without knowing exactly what the active factors are that make the treatment work in mice. This space has attracted both established players in the plasmapheresis field – Alkahest and Grifols have teamed up to test fractions of whole plasma in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's – but also direct-to-consumer operations like Ambrosia that just want to offer patients access to treatments without regulatory oversight.

But the bold claims of improved vigor thanks to young blood are so far unsupported by clinical evidence. We simply haven't performed trials to test whether dosing a mostly healthy person with plasma can slow down aging, at least not yet. There is some evidence that plasma replacement works in mice, yes, but those experiments are all done in very different systems than what a human receiving young plasma might experience. To date, I have not seen any plasma transfusion clinic doing young blood plasmapheresis propose a clinical trial that is anything more than a shallow advertisement for their procedures.

The efforts I have seen to perform prophylactic plasmapheresis will fail to impact societal health. Without clearly defined endpoints and proper clinical trials, we won't know whether the procedure really lowers the risk of disease or helps with conditions of aging. So even if their hypothesis is correct, the lack of strong evidence to fall back on means that the procedure will never spread beyond the fringe groups willing to take the risk. If their hypothesis is wrong, then people are paying a huge amount of money for false hope, just as they do, sadly, at the phony stem cell clinics that started popping up all through the 2000s when stem cell hype was at its peak.

Until then, prophylactic plasma transfusions will be the domain of the optimistic and the gullible.

The real progress in the field will be made slowly, using carefully defined products either directly isolated from blood or targeting a bloodborne factor, just as the serious pharma and biotech players are doing already.

The field will progress in stages, first creating and carefully testing treatments for well-defined diseases, and only then will it progress to large-scale clinical trials in relatively healthy people to look for the prevention of disease. Most of us will choose to wait for this second stage of trials before undergoing any new treatments. Until then, prophylactic plasma transfusions will be the domain of the optimistic and the gullible.

Who’s Responsible for Curbing the Teen Vaping Epidemic?

A teenage girl vaping in a park.

E-cigarettes are big business. In 2017, American consumers bought more than $250 million in vapes and juice-filled pods, and spent $1 billion in 2018. By 2023, the global market could be worth $44 billion a year.

"My nine-year-old actually knows what Juuling is. In many cases the [school] bathroom is now referred to as 'the Juuling room.'"

Investors are trying to capitalize on the phenomenal growth. In July 2018, Juul Labs, the company that owns 70 percent of the U.S. e-cigarette market share, raised $1.25 billion at a $16 billion valuation, then sold a 35 percent stake to Phillip Morris USA owner Altria Group in December. The second transaction valued the company at $38 billion. While the traditional tobacco market remains much larger, it's projected to grow at less than two percent a year, making the attractiveness of the rapidly expanding e-cigarette market obvious.

While Juul and other e-cigarette manufacturers argue that their products help adults quit smoking – and there's some research to back this narrative up – much of the growth has been driven by children and teenagers. One CDC study showed a 48 percent rise in e-cigarette use by middle schoolers and a 78 percent increase by high schoolers between 2017 and 2018, a jump from 1.5 million kids to 3.6 million. In response to the study, F.D.A. Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said, "We see clear signs that youth use of electronic cigarettes has reached an epidemic proportion."

Another study found that teenagers between 15 and 17 were 16 times more likely to use Juul than people aged 25-34. In December, Surgeon General Jerome Adams said, "My nine-year-old actually knows what Juuling is. In many cases the [school] bathroom is now referred to as 'the Juuling room.'"

And the product is seriously addictive. A single Juul pod contains as much nicotine as a pack of 20 regular cigarettes. Considering that 90 percent of smokers are addicted by 18 years old, it's clear that steps need to be taken to combat the growing epidemic.

But who should take the lead? Juul and other e-cigarette companies? The F.D.A. and other government regulators? Schools? Parents?

The Surgeon General's website has a list of earnest possible texts that parents can send to their teens to dissuade them from Juuling, like: "Hope none of your friends use e-cigarettes around you. Even breathing the cloud they exhale can expose you to nicotine and chemicals that can be dangerous to your health." While parents can attempt to police their teens, many experts believe that the primary push should come at a federal level.

The regulation battle has already begun. In September, the F.D.A. announced that Juul had 60 days to show a plan that would prevent youth from getting their hands on the product. The result was for the company to announce that it wouldn't sell flavored pods in retail stores except for tobacco, menthol, and mint; Juul also shuttered its Instagram and Facebook accounts. These regulations mirrored an F.D.A. mandate two days later that required flavored e-cigarettes to be sold in closed-off areas. "This policy will make sure the fruity flavors are no longer accessible to kids in retail sites, plan and simple," Commissioner Gottlieb said when announcing the moves. "That's where they're getting access to the e-cigs and we intend to end those sales."

"There isn't a great history of the tobacco industry acting responsibly and being able to in any way police itself."

While so far, Gottlieb – who drew concerns about conflict of interest due to his past position as a board member at e-cigarette company, Kure – has pleased anti-smoking advocates with his efforts, some observers also argue that it needs to go further. "Overall, we didn't know what to expect when a new commissioner came in, but it's been quite refreshing how much attention has been paid to the tobacco industry by the F.D.A.," Robin Koval, CEO and president of Truth Initiative, said a day after the F.D.A. announced the proposed regulations. "It's important to have a start. I certainly want to give credit for that. But we were really hoping and feel that what was announced...doesn't go far enough."

The issue is the industry's inability or unwillingness to police itself in the past. Juul, however, claims that it's now proactively working to prevent young people from taking up its product. "Juul Labs and F.D.A. share a common goal – preventing youth from initiating on nicotine," a company representative said in an email. "To paraphrase Commissioner Gottlieb, we want to be the off-ramp for adult smokers to switch from cigarettes, not an on-ramp for America's youth to initiate on nicotine. We won't be successful in our mission to serve adult smokers if we don't narrow the on-ramp... Our intent was never to have youth use Juul products. But intent is not enough, the numbers are what matter, and the numbers tell us underage use of e-cigarette products is a problem. We must solve it."

Juul argues that its products help adults quit – even offering a calculator on the website showing how much people will save – and that it didn't target youth. But studies show otherwise. Furthermore, the youth smoking prevention curriculum the company released was poorly received. "It's what Philip Morris did years ago," said Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, a professor of pediatrics at Stanford who helped author a study on the program's faults. "They aren't talking about their named product. They are talking about vapes or e-cigarettes. Youth don't consider Juuls to be vapes or e-cigarettes. [Teens] don't talk about flavors. They don't talk about marketing. They did it to look good. But if you look at what [Juul] put together, it's a pretty awful curriculum that was put together pretty quickly."

The American Lung Association gave the FDA an "F" for failing to take mint and menthol e-cigs off the market, since those flavors remain popular with teens.

Add this all up, and in the end, it's hard to see the industry being able to police itself, critics say. Neither the past examples of other tobacco companies nor the present self-imposed regulations indicate that this will succeed.

"There isn't a great history of the tobacco industry acting responsibly and being able to in any way police itself," Koval said. "That job is best left to the F.D.A., and to the states and localities in what they can regulate and legislate to protect young people."

Halpern-Felsher agreed. "I think we need independent bodies. I really don't think that a voluntary ban or a regulation on the part of the industry is a good idea, nor do I think it will work," she said. "It's pretty much the same story, of repeating itself."

Just last week, the American Association of Pediatrics issued a new policy statement calling for the F.D.A. to immediately ban the sale of e-cigarettes to anyone under age 21 and to prohibit the online sale of vaping products and solutions, among other measures. And in its annual report, the American Lung Association gave the F.D.A. an "F" for failing to take mint and menthol e-cigs off the market, since those flavors remain popular with teens.

Few, if any people involved, want more regulation from the federal government. In an ideal world, this wouldn't be necessary. But many experts agree that it is. Anything else is just blowing smoke.