How 30 Years of Heart Surgeries Taught My Dad How to Live

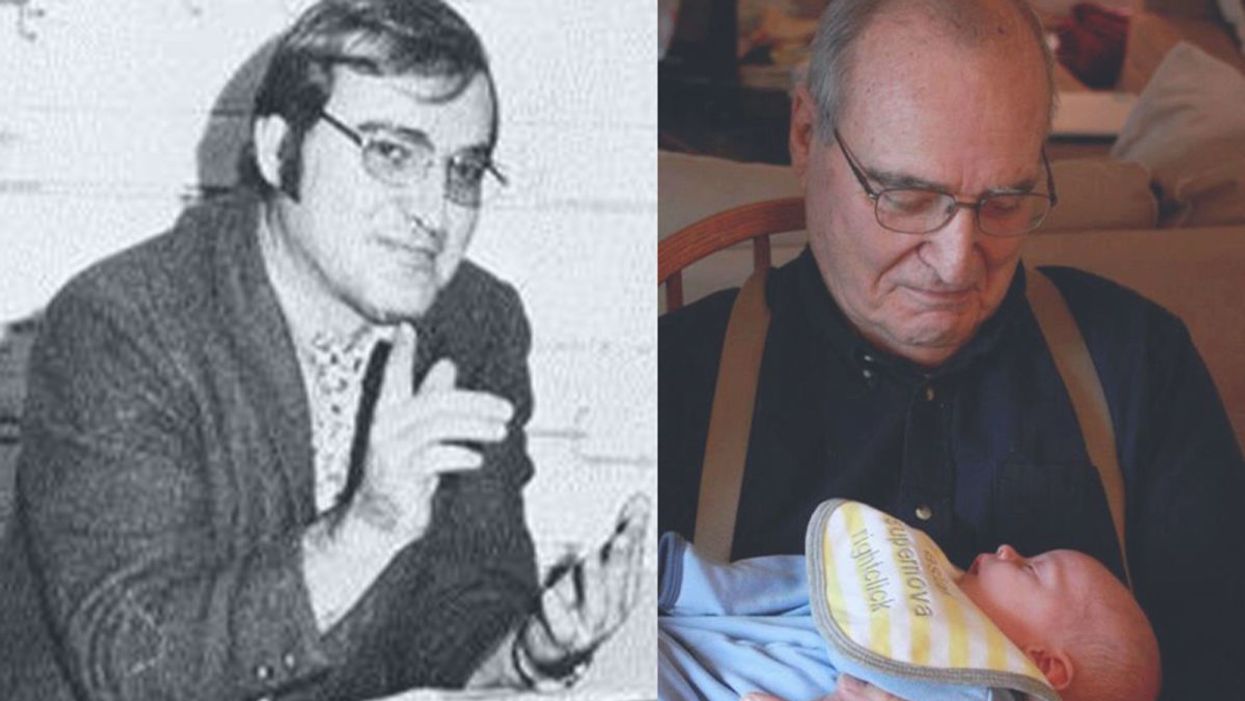

A mid-1970s photo of the author's father, and him holding a grandchild in 2012.

[Editor's Note: This piece is the winner of our 2019 essay contest, which prompted readers to reflect on the question: "How has an advance in science or medicine changed your life?"]

My father did not expect to live past the age of 50. Neither of his parents had done so. And he also knew how he would die: by heart attack, just as his father did.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday.

My dad lived the first 40 years of his life with this knowledge buried in his bones. He started smoking at the age of 12, and was drinking before he was old enough to enlist in the Navy. He had a sarcastic, often cruel, sense of humor that could drive my mother, my sister and me into tears. He was not an easy man to live with, but that was okay by him - he didn't expect to live long.

In July of 1976, he had his first heart attack, days before his 40th birthday. I was 13, and my sister was 11. He needed quadruple bypass surgery. Our small town hospital was not equipped to do this type of surgery; he would have to be transported 40 miles away to a heart center. I understood this journey to mean that my father was seriously ill, and might die in the hospital, away from anyone he knew. And my father knew a lot of people - he was a popular high school English teacher, in a town with only three high schools. He knew generations of students and their parents. Our high school football team did a blood drive in his honor.

During a trip to Disney World in 1974, Dad was suffering from angina the entire time but refused to tell me (left) and my sister, Kris.

Quadruple bypass surgery in 1976 meant that my father's breastbone was cut open by a sternal saw. His ribcage was spread wide. After the bypass surgery, his bones would be pulled back together, and tied in place with wire. The wire would later be pulled out of his body when the bones knitted back together. It would take months before he was fully healed.

Dad was in the hospital for the rest of the summer and into the start of the new school year. Going to visit him was farther than I could ride my bicycle; it meant planning a trip in the car and going onto the interstate. The first time I was allowed to visit him in the ICU, he was lying in bed, and then pushed himself to sit up. The heart monitor he was attached to spiked up and down, and I fainted. I didn't know that heartbeats change when you move; television medical dramas never showed that - I honestly thought that I had driven my father into another heart attack.

Only a few short years after that, my father returned to the big hospital to have his heart checked with a new advance in heart treatment: a CT scan. This would allow doctors to check for clogged arteries and treat them before a fatal heart attack. The procedure identified a dangerous blockage, and my father was admitted immediately. This time, however, there was no need to break bones to get to the problem; my father was home within a month.

During the late 1970's, my father changed none of his habits. He was still smoking, and he continued to drink. But now, he was also taking pills - pills to manage the pain. He would pop a nitroglycerin tablet under his tongue whenever he was experiencing angina (I have a vivid memory of him doing this during my driving lessons), but he never mentioned that he was in pain. Instead, he would snap at one of us, or joke that we were killing him.

I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count.

Being the kind of guy he was, my father never wanted to talk about his health. Any admission of pain implied that he couldn't handle pain. He would try to "muscle through" his angina, as if his willpower would be stronger than his heart muscle. His efforts would inevitably fail, leaving him angry and ready to lash out at anyone or anything. He would blame one of us as a reason he "had" to take valium or pop a nitro tablet. Dinners often ended in shouts and tears, and my father stalking to the television room with a bottle of red wine.

In the 1980's while I was in college, my father had another heart attack. But now, less than 10 years after his first, medicine had changed: our hometown hospital had the technology to run dye through my father's blood stream, identify the blockages, and do preventative care that involved statins and blood thinners. In one case, the doctors would take blood vessels from my father's legs, and suture them to replace damaged arteries around his heart. New advances in cholesterol medication and treatments for angina could extend my father's life by many years.

My father decided it was time to quit smoking. It was the first significant health step I had ever seen him take. Until then, he treated his heart issues as if they were inevitable, and there was nothing that he could do to change what was happening to him. Quitting smoking was the first sign that my father was beginning to move out of his fatalistic mindset - and the accompanying fatal behaviors that all pointed to an early death.

In 1986, my father turned 50. He had now lived longer than either of his parents. The habits he had learned from them could be changed. He had stopped smoking - what else could he do?

It was a painful decade for all of us. My parents divorced. My sister quit college. I moved to the other side of the country and stopped speaking to my father for almost 10 years. My father remarried, and divorced a second time. I stopped counting the number of times he was in and out of the hospital with heart-related issues.

In the early 1990's, my father reached out to me. I think he finally determined that, if he was going to have these extra decades of life, he wanted to make them count. He traveled across the country to spend a week with me, to meet my friends, and to rebuild his relationship with me. He did the same with my sister. He stopped drinking. He was more forthcoming about his health, and admitted that he was taking an antidepressant. His humor became less cruel and sadistic. He took an active interest in the world. He became part of my life again.

The 1990's was also the decade of angioplasty. My father explained it to me like this: during his next surgery, the doctors would place balloons in his arteries, and inflate them. The balloons would then be removed (or dissolve), leaving the artery open again for blood. He had several of these surgeries over the next decade.

When my father was in his 60's, he danced at with me at my wedding. It was now 10 years past the time he had expected to live, and his life was transformed. He was living with a woman I had known since I was a child, and my wife and I would make regular visits to their home. My father retired from teaching, became an avid gardener, and always had a home project underway. He was a happy man.

Dancing with my father at my wedding in 1998.

Then, in the mid 2000's, my father faced another serious surgery. Years of arterial surgery, angioplasty, and damaged heart muscle were taking their toll. He opted to undergo a life-saving surgery at Cleveland Clinic. By this time, I was living in New York and my sister was living in Arizona. We both traveled to the Midwest to be with him. Dad was unconscious most of the time. We took turns holding his hand in the ICU, encouraging him to regain his will to live, and making outrageous threats if he didn't listen to us.

The nursing staff were wonderful. I remember telling them that my father had never expected to live this long. One of the nurses pointed out that most of the patients in their ward were in their 70's and 80's, and a few were in their 90's. She reminded me that just a decade earlier, most hospitals were unwilling to do the kind of surgery my father had received on patients his age. In the first decade of the 21st century, however, things were different: 90-year-olds could now undergo heart surgery and live another decade. My father was on the "young" side of their patients.

The Cleveland Clinic visit would be the last major heart surgery my father would have. Not that he didn't return to his local hospital a few times after that: he broke his neck -- not once, but twice! -- slipping on ice. And in the 2010's, he began to show signs of dementia, and needed more home care. His partner, who had her own health issues, was not able to provide the level of care my father needed. My sister invited him to move in with her, and in 2015, I traveled with him to Arizona to get him settled in.

After a few months, he accepted home hospice. We turned off his pacemaker when the hospice nurse explained to us that the job of a pacemaker is to literally jolt a patient's heart back into beating. The jolts were happening more and more frequently, causing my Dad additional, unwanted pain.

My father in 2015, a few months before his death.

My father died in February 2016. His body carried the scars and implants of 30 years of cardiac surgeries, from the ugly breastbone scar from the 1970's to scars on his arms and legs from borrowed blood vessels, to the tiny red circles of robotic incisions from the 21st century. The arteries and veins feeding his heart were a patchwork of transplanted leg veins and fragile arterial walls pressed thinner by balloons.

And my father died with no regrets or unfinished business. He died in my sister's home, with his long-time partner by his side. Medical advancements had given him the opportunity to live 30 years longer than he expected. But he was the one who decided how to live those extra years. He was the one who made the years matter.

How Can We Decide If a Biomedical Advance Is Ethical?

A newborn in the maternity ward. (© rufous/Fotolia)

"All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned…"

On July 25, 1978, Louise Brown was born in Oldham, England, the first human born through in vitro fertilization, through the work of Patrick Steptoe, a gynecologist, and Robert Edwards, a physiologist. Her birth was greeted with strong (though not universal) expressions of ethical dismay. Yet in 2016, the latest year for which we have data, nearly two percent of the babies born in the United States – and around the same percentage throughout the developed world – were the result of IVF. Few, if any, think of these children as unnatural, monsters, or freaks or of their parents as anything other than fortunate.

How should we view Dr. He today, knowing that the world's eventual verdict on the ethics of biomedical technologies often changes?

On November 25, 2018, news broke that Chinese scientist, Dr. He Jiankui, claimed to have edited the genomes of embryos, two of whom had recently become the new babies, Lulu and Nana. The response was immediate and overwhelmingly negative.

Times change. So do views. How will Dr. He be viewed in 40 years? And, more importantly, how should we view him today, knowing that the world's eventual verdict on the ethics of biomedical technologies often changes? And when what biomedicine can do changes with vertiginous frequency?

How to determine what is and isn't ethical is above my pay grade. I'm a simple law professor – I can't claim any deeper insight into how to live a moral life than the millennia of religious leaders, philosophers, ethicists, and ordinary people trying to do the right thing. But I can point out some ways to think about these questions that may be helpful.

First, consider two different kinds of ethical commands. Some are quite specific – "thou shalt not kill," for example. Others are more general – two of them are "do unto others as you would have done to you" or "seek the greatest good for the greatest number."

Biomedicine in the last two centuries has often surprised us with new possibilities, situations that cultures, religions, and bodies of ethical thought had not previously had to consider, from vaccination to anesthesia for women in labor to genome editing. Sometimes these possibilities will violate important and deeply accepted precepts for a group or a person. The rise of blood transfusions around World War I created new problems for Jehovah's Witnesses, who believe that the Bible prohibits ingesting blood. The 20th century developments of artificial insemination and IVF both ran afoul of Catholic doctrine prohibiting methods other than "traditional" marital intercourse for conceiving children. If you subscribe to an ethical or moral code that contains prohibitions that modern biomedicine violates, the issue for you is stark – adhere to those beliefs or renounce them.

If the harms seem to outweigh the benefits, it's easy to conclude "this is worrisome."

But many biomedical changes violate no clear moral teachings. Is it ethical or not to edit the DNA of embryos? Not surprisingly, the sacred texts of various religions – few of which were created after, at the latest, the early 19th century, say nothing specific about this. There may be hints, precedents, leanings that could argue one way or another, but no "commandments." In that case, I recommend, at least as a starting point, asking "what are the likely consequences of these actions?"

Will people be, on balance, harmed or helped by them? "Consequentialist" approaches, of various types, are a vast branch of ethical theories. Personally I find a completely consequentialist approach unacceptable – I could not accept, for example, torturing an innocent child even in order to save many lives. But, in the absence of a clear rule, looking at the consequences is a great place to start. If the harms seem to outweigh the benefits, it's easy to conclude "this is worrisome."

Let's use that starting place to look at a few bioethical issues. IVF, for example, once proven (relatively) safe seems to harm no one and to help many, notably the more than 8 million children worldwide born through IVF since 1978 – and their 16 million parents. On the other hand, giving unknowing, and unconsenting, intellectually disabled children hepatitis A harmed them, for an uncertain gain for science. And freezing the heads of the dead seems unlikely to harm anyone alive (except financially) but it also seems almost certain not to benefit anyone. (Those frozen dead heads are not coming back to life.)

Now let's look at two different kinds of biomedical advances. Some are controversial just because they are new; others are controversial because they cut close to the bone – whether or not they violate pre-established ethical or moral norms, they clearly relate to them.

Consider anesthesia during childbirth. When first used, it was controversial. After all, said critics, in Genesis, the Bible says God told Eve, "I will greatly multiply Your pain in childbirth, In pain you will bring forth children." But it did not clearly prohibit pain relief and from the advent of ether on, anesthesia has been common, though not universal, in childbirth in western societies. The pre-existing ethical precepts were not clear and the consequences weighed heavily in favor of anesthesia. Similarly, vaccination seems to violate no deep moral principle. It was, and for some people, still is just strange, and unnatural. The same was true of IVF initially. Opposition to all of these has faded with time and familiarity. It has not disappeared – some people continue to find moral or philosophical problems with "unnatural" childbirth, vaccination, and IVF – but far fewer.

On the other hand, human embryonic stem cell research touches deeper issues. Human embryos are destroyed to make those stem cells. Reasonable people disagree on the moral status of the human embryo, and the moral weight of its destruction, but it does at least bring into play clear and broadly accepted moral precepts, such as "Thou shalt not kill." So, at the far side of an individual's time, does euthanasia. More exposure to, and familiarity with, these practices will not necessarily lead to broad acceptance as the objections involve more than novelty.

The first is "what would I do?" The second – what should my government, culture, religion allow or forbid?

Finally, all this ethical analysis must work at two levels. The first is "what would I do?" The second – what should my government, culture, religion allow or forbid? There are many things I would not do that I don't think should be banned – because I think other people may reasonably have different views from mine. I would not get cosmetic surgery, but I would not ban it – and will try not to think ill of those who choose it

So, how should we assess the ethics of new biomedical procedures when we know that society's views may change? More specifically, what should we think of He Jiankui's experiment with human babies?

First, look to see whether the procedure in question violates, at least fairly clearly, some rule in your ethical or moral code. If so, your choice may not be difficult. But if the procedure is unmentioned in your moral code, probably because it was inconceivable to the code's creators, examine the consequences of the act.

If the procedure is just novel, and not something that touches on important moral concerns, looking at the likely consequences may be enough for your ethical analysis –though it is always worth remembering that predicting consequences perfectly is impossible and predicting them well is never certain. If it does touch on morally significant issues, you need to think those issues through. The consequences may be important to your conclusions but they may not be determinative.

And, then, if you conclude that it is not ethical from your perspective, you need to take yet another step and consider whether it should be banned for people who do not share your perspective. Sometimes the answer will be yes – that psychopaths may not view murder as immoral does not mean we have to let them kill – but sometimes it will be no.

What does this say about He Jiankui's experiment? I have no qualms in condemning it, unequivocally. The potential risks to the babies grossly outweighed any benefits to them, and to science. And his secret work, against a near universal scientific consensus, privileged his own ethical conclusions without giving anyone else a vote, or even a voice.

But if, in ten or twenty years, genome editing of human embryos is shown to be safe (enough) and it is proposed to be used for good reasons – say, to relieve human suffering that could not be treated in other good ways – and with good consents from those directly involved as well as from the relevant society and government – my answer might well change. Yours may not. Bioethics is a process for approaching questions; it is not a set of universal answers.

This article opened with a quotation from the 1848 Communist Manifesto, referring to the dizzying pace of change from industrialization and modernity. You don't need to be a Marxist to appreciate that sentiment. Change – especially in the biosciences – keeps accelerating. How should we assess the ethics of new biotechnologies? The best we can, with what we know, at the time we inhabit. And, in the face of vast uncertainty, with humility.

This Brain Doc Has a “Repulsive” Idea to Make Football Safer

A football player making a tackle during a game. (© Joe/Fotolia)

What do football superstars Tom Brady, Drew Brees, Philip Rivers, and Adrian Peterson all have in common? Last year they wore helmets that provided the poorest protection against concussions in all the NFL.

"You're only as protected as well as the worst helmet that's out there."

A Dangerous Policy

Football helmets are rated on a one-star to five-star system based on how well they do the job of protecting the player. The league has allowed players to use their favorites, regardless of the star rating.

The Oxford-trained neuroscientist Ray Colello conducted a serious analysis of just how much the protection can vary between each level of star rating. Colello and his team of graduate students sifted through two seasons of game video to identify which players were wearing what helmets. There was "a really good correlation with position, but the correlation is much more significant based on age."

"The average player in the NFL is 26.6 years old, but the average age of a player wearing a one-star helmet is 34. And for anyone who knows football, that's ancient," the brain doc says. "Then for our two-star helmet, it's 32; and for a three-star helmet it's 29." Players were sticking with the helmets they were familiar with in college, despite the fact that equipment had improved considerably in recent years.

"You're only as protected as well as the worst helmet that's out there," Colello explains. Offering an auto analogy, he says, "It's like, if you run into the back of a Pinto, even if you are in a five-star Mercedes, that gas tank may still explode and you are still going to die."

It's one thing for a player to take a risk at scrambling his own brain; it's another matter to put a teammate or opponent at needless risk. Colello published his analysis early last year and the NFL moved quickly to ban the worst performing helmets, starting next season.

Some of the 14 players using the soon-to-be-banned helmets, like Drew Brees and Philip Rivers, made the switch to a five-star helmet at the start of training camp and stayed with it. Adrian Peterson wore a one-star helmet throughout the season.

Tom Brady tried but just couldn't get comfortable with a new bonnet and, after losing a few games, switched back to his old one in the middle of the season; he says he's going to ask the league to "grandfather in" his old helmet so he can continue to use it.

As for Colello, he's only just getting started. The brain doc has a much bigger vision for the future of football safety. He wants to prevent concussions from even occurring in the first place by creating an innovative new helmet that's unlike anything the league has ever seen.

Oxford-trained neuroscientist Ray Colello is on a mission to make football safer.

(Photo credit: VCU public affairs)

"A Force Field" of Protection

His inspiration was serendipitous; he was at home watching a football game on TV when Denver Bronco's receiver Wes Welker was hit, lay flat on the field with a concussion, and was carted off. As a commercial flickered on the screen, he ambled into the kitchen for another beer. "What those guys need is a force field protecting them," he thought to himself.

Like so many households, the refrigerator door was festooned with magnets holding his kids' school work in place. And in that eureka moment the idea popped into his head: "Maybe the repulsive force of magnets can put a break on an impact before it even occurs." Colello has spent the last few years trying to turn his concept into reality.

Newton's laws of physics – mass and speed – play out graphically in a concussion. The sudden stop of a helmet-to-helmet collision can shake the brain back and forth inside the skull like beans in a maraca. Dried beans stand up to the impact, making their distinctive musical sound; living brain tissue is much softer and not nearly so percussive. The resulting damage is a concussion.

The risk of that occurring is greater than you might think. Researchers using accelerometers inside helmets have determined that a typical college football player experiences about 600 helmet-to-helmet contacts during a season of practice and games. Each hit generates a split second peak g-force of 20 to 150 within the helmet and the odds of one causing a concussion increase sharply over 100 gs of force.

By comparison, astronauts typically experience a maximum sustained 3gs during lift off and most humans will black out around 9gs, which is why fighter pilots wear special pressure suits to counter the effects.

"It stretches the time line of impact quite dramatically. In fact in most instances, it doesn't even hit."

The NFL's fastest player, Chris Johnson, can run 19.3 mph. A collision at that speed "produces 120gs worth of force," Colello explains. "But if you can extend that time of impact by just 5 milliseconds (from 12 to 17msec) you'll shift that g-force down to 84. There is a very good chance that he won't suffer a concussion."

The neuroscientist dived into learning all he could about the physics magnets. It turns out that the most powerful commercially available magnet is an alloy made of neodymium, iron, and boron. The elements can be mixed and glued together in any shape and then an electric current is run through to make it magnetic; the direction of the current establishes the north-south poles.

A 1-pound neodymium magnet can repulse 600 times its own weight, even though the magnetic field extends less than an inch. That means it can push back a magnet inside another helmet but not affect the brain.

Crash Testing the Magnets

Colello couldn't wait to see if his idea panned out. With blessing from his wife to use their credit card, he purchased some neodymium magnets and jury-rigged experiments at home.

The reinforced plastics used in football helmets don't affect the magnetic field. And the small magnets stopped weights on gym equipment that were dropped from various heights. "It stretches the time line of impact quite dramatically. In fact in most instances, it doesn't even hit," says Colello. "We are dramatically shifting the curve" of impact.

Virginia Commonwealth University stepped in with a $50,000 innovation grant to support the next research steps. The professor ordered magnets custom-designed to fit the curvature of space inside the front and sides of existing football helmets. That makes it impossible to install them the wrong way, and ensures the magnets' poles will always repel and not attract. It adds about a pound and a half to the weight of the helmet.

a) The brain in a helmet. b) Placing the magnet. c) Measuring the impact of a helmet-to-helmet collision. d) How magnets reduce the force of impact.

(Courtesy Ray Colello)

Colello rented crash test dummy heads crammed with accelerometers and found that the magnets performed equally well at slowing collisions when fixed to a pendulum in a test that approximated a helmet and head hitting a similarly equipped helmet. It impressively reduced the force of contact.

The NFL was looking for outside-the-box thinking to prevent concussions. It was intrigued by Colello's approach and two years ago invited him to submit materials for review. To be fair to all entrants, the league proposed to subject all entries to the same standard crush test to see how well each performed in lessening impact. The only trouble was, Colello's approach was designed to avoid collisions, not lessen their impact. The test wouldn't have been a valid evaluation and he withdrew from consideration.

But Colello's work caught the attention of Stefan Duma, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech who developed the five-star rating system for football helmets.

"In theory it makes sense to use [the magnets] to slow down or reduce acceleration, that's logical," says Duma. He believes current helmet technology is nearing "the end of the physics barrier; you can only absorb so much energy in so much space," so the field is ripe for new approaches to improve helmet technology.

However, one of Duma's concerns is whether magnets "are feasible from a weight standpoint." Most helmets today weigh between two and four pounds, and a sufficiently powerful magnet might add too much weight. One possibility is using an electromagnet, which potentially could be lighter and more powerful, particularly if the power supply could be carried lower in the body, say in the shoulder pads.

Colello says his lab tests are promising enough that the concept needs to be tried out on the playing field. "We need to make enough helmets for two teams to play each other in a regulation-style game and measure the impact forces that are generated on each, and see if there is a significant reduction." He is waiting to hear from the National Institutes of Health on a grant proposal to take that next step toward dramatically reducing the risk of concussions in the NFL.

Just five milliseconds could do it.