How Genetic Engineering Could Save the Coral Reefs

Underwater world with corals and tropical fish.

Coral reefs are usually relegated to bit player status in television and movies, providing splashes of background color for "Shark Week," "Finding Nemo," and other marine-based entertainment.

In real life, the reefs are an absolutely crucial component of the ecosystem for both oceans and land, rivaling only the rain forests in their biological complexity. They provide shelter and sustenance for up to a quarter of all marine life, oxygenate the water, help protect coastlines from erosion, and support thousands of tourism jobs and businesses.

Genetic engineering could help scientists rebuild the reefs that have been lost, and turn those still alive into a souped-up version that can withstand warmer and even more acidic waters.

But the warming of the world's oceans -- exacerbated by an El Nino event that occurred between 2014 and 2016 -- has been putting the world's reefs under tremendous pressure. Their vibrant colors are being replaced by sepulchral whites and tans.

That's the result of bleaching -- a phenomenon that occurs when the warming waters impact the efficiency of the algae that live within the corals in a symbiotic relationship, providing nourishment via photosynthesis and eliminating waste products. The corals will often "shuffle" their resident algae, reacting in much the same way a landlord does with a non-performing tenant -- evicting them in the hopes of finding a better resident. But when better-performing algae does not appear, the corals become malnourished, eventually becoming deprived of their color and then their lives.

The situation is dire: Two-thirds of Australia's Great Barrier Reef have undergone a bleaching event in recent years, and it's believed up to half of that reef has died.

Moreover, hard corals are the ocean's redwood trees. They take centuries to grow, meaning it could take centuries or more to replace them.

Recent developments in genetic engineering -- and an accidental discovery by researchers at a Florida aquarium -- provide opportunities for scientists to potentially rebuild a large proportion of the reefs that have been lost, and perhaps turn those still alive into a souped-up version that can withstand warmer and even more acidic waters. But many questions have yet to be answered about both the biological impact on the world's oceans, and the ethics of reengineering the linchpin of its ecosystem.

How did we get here?

Coral bleaching was a regular event in the oceans even before they began to warm. As a result, natural selection weeds out the weaker species, says Rachel Levin, an American-born scientist who has performed much of her graduate work in Australia. But the current water warming trend is happening at a much higher rate than it ever has in nature, and neither the coral nor the algae can keep up.

"There is a big concern about giving one variant a huge fitness advantage, have it take over and impact the natural variation that is critical in changing environments."

In a widely-read paper published last year in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology, Levin and her colleagues put forth a fairly radical notion for preserving the coral reefs: Genetically modify their resident algae.

Levin says the focus on algae is a pragmatic decision. Unlike coral, they reproduce extremely rapidly. In theory, a modified version could quickly inhabit and stabilize a reef. About 70 percent of algae -- all part of the genus symbiodinium -- are host generalists. That means they will insert themselves into any species of coral.

In recent years, work on mapping the genomes of both algae and coral has been progressing rapidly. Scientists at Stanford University have recently been manipulating coral genomes using larvae manipulated with the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, although the experimentation has mostly been limited to its fluorescence.

Genetically modifying the coral reefs could seem like a straightforward proposition, but complications are on the horizon. Levin notes that as many as 20 different species of algae can reside within a single coral, so selecting the best ones to tweak may pose a challenge.

"The entire genus is made up of thousands of subspecies, all very genetically distinct variants. There is a huge genetic diversity, and there is a big concern about giving one variant a huge fitness advantage, have it take over and impact the natural variation that is critical in changing environments," Levin says.

Genetic modifications to an algae's thermal tolerance also poses the risk of what Levin calls an "off-target effect." That means a change to one part of the genome could lead to changes in other genes, such as those regulating growth, reproduction, or other elements crucial to its relationship with coral.

Phillip Cleves, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford who has participated in the CRISPR/Cas9 work, says that future research will focus on studying the genes in coral that regulate the relationship with the algae. But he is so concerned about the ethical issues of genetically manipulating coral to adapt to a changing climate that he declined to discuss it in detail. And most coral species have not yet had their genomes fully mapped, he notes, suggesting that such work could still take years.

An Alternative: Coral Micro-fragmentation

In the meantime, there is another technique for coral preservation led by David Vaughan, senior scientist and program manager at the Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium in Sarasota, Florida.

Vaughan's research team has been experimenting in the past decade with hard coral regeneration. Their work had been slow and painstaking, since growing larvae into a coral the size of a quarter takes three years.

The micro-fragmenting process in some ways raises fewer ethical questions than genetically altering the species.

But then, one day in 2006, Vaughan accidentally broke off a tiny piece of coral in the research aquarium. That fragment grew to the size of a quarter in three months, apparently the result of the coral's ability to rapidly regenerate when injured. Further research found that breaking coral in this manner -- even to the size of a single polyp -- led to rapid growth in more than two-dozen species.

Mote is using this process, known as micro-fragmentation, to grow large numbers of coral rapidly, often fusing them on top of larger pieces of dead coral. These coral heads are then planted in the Florida Keys, which has experienced bleaching events over 12 of the last 14 years. The process has sped up almost exponentially; Mote has planted some 36,000 pieces of coral to date, but Vaughan says it's on track to plant 35,000 more pieces this year alone. That sum represents between 20 to 30 acres of restored reef. Mote is on track to plant another 100,000 pieces next year.

This rapid reproduction technique in some ways allows Mote scientists to control for the swift changes in ocean temperature, acidification and other factors. For example, using surviving pieces of coral from areas that have undergone bleaching events means these hardier strains will propagate much faster than nature allows.

Vaughan recently visited the Yucatan Peninsula to work with Mexican researchers who are going to embark on a micro-fragmenting initiative of their own.

The micro-fragmenting process in some ways raises fewer ethical questions than genetically altering the species, although Levin notes that this could also lead to fewer varieties of corals on the ocean floor -- a potential flattening of the colorful backdrops seen in television and movies.

But Vaughan has few qualms, saying this is an ecological imperative. He suggests that micro-fragmentation could serve as a stopgap until genomic technologies further advance.

"We have to use the technology at hand," he says. "This is a lot like responding when a forest burns down. We don't ask questions. We plant trees."

The future of non-hormonal birth control: Antibodies can stop sperm in their tracks

Many women want non-hormonal birth control. A 22-year-old's findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

Unwanted pregnancy can now be added to the list of preventions that antibodies may be fighting in the near future. For decades, really since the 1980s, engineered monoclonal antibodies have been knocking out invading germs — preventing everything from cancer to COVID. Sperm, which have some of the same properties as germs, may be next.

Not only is there an unmet need on the market for alternatives to hormonal contraceptives, the genesis for the original research was personal for the then 22-year-old scientist who led it. Her findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

The genesis

It’s Suruchi Shrestha’s research — published in Science Translational Medicine in August 2021 and conducted as part of her dissertation while she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — that could change the future of contraception for many women worldwide. According to a Guttmacher Institute report, in the U.S. alone, there were 46 million sexually active women of reproductive age (15–49) who did not want to get pregnant in 2018. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade this year, Shrestha’s research could, indeed, be life changing for millions of American women and their families.

Now a scientist with NextVivo, Shrestha is not directly involved in the development of the contraceptive that is based on her research. But, back in 2016 when she was going through her own problems with hormonal contraceptives, she “was very personally invested” in her research project, Shrestha says. She was coping with a long list of negative effects from an implanted hormonal IUD. According to the Mayo Clinic, those can include severe pelvic pain, headaches, acute acne, breast tenderness, irregular bleeding and mood swings. After a year, she had the IUD removed, but it took another full year before all the side effects finally subsided; she also watched her sister suffer the “same tribulations” after trying a hormonal IUD, she says.

For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, Shrestha says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

Shrestha unshelved antibody research that had been sitting idle for decades. It was in the late 80s that scientists in Japan first tried to develop anti-sperm antibodies for contraceptive use. But, 35 years ago, “Antibody production had not been streamlined as it is now, so antibodies were very expensive,” Shrestha explains. So, they shifted away from birth control, opting to focus on developing antibodies for vaccines.

Over the course of the last three decades, different teams of researchers have been working to make the antibody more effective, bringing the cost down, though it’s still expensive, according to Shrestha. For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, she says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

The problem

The problem with contraceptives for women, Shrestha says, is that all but a few of them are hormone-based or have other negative side effects. In fact, some studies and reports show that millions of women risk unintended pregnancy because of medical contraindications with hormone-based contraceptives or to avoid the risks and side effects. While there are about a dozen contraceptive choices for women, there are two for men: the condom, considered 98% effective if used correctly, and vasectomy, 99% effective. Neither of these choices are hormone-based.

On the non-hormonal side for women, there is the diaphragm which is considered only 87 percent effective. It works better with the addition of spermicides — Nonoxynol-9, or N-9 — however, they are detergents; they not only kill the sperm, they also erode the vaginal epithelium. And, there’s the non-hormonal IUD which is 99% effective. However, the IUD needs to be inserted by a medical professional, and it has a number of negative side effects, including painful cramping at a higher frequency and extremely heavy or “abnormal” and unpredictable menstrual flows.

The hormonal version of the IUD, also considered 99% effective, is the one Shrestha used which caused her two years of pain. Of course, there’s the pill, which needs to be taken daily, and the birth control ring which is worn 24/7. Both cause side effects similar to the other hormonal contraceptives on the market. The ring is considered 93% effective mostly because of user error; the pill is considered 99% effective if taken correctly.

“That’s where we saw this opening or gap for women. We want a safe, non-hormonal contraceptive,” Shrestha says. Compounding the lack of good choices, is poor access to quality sex education and family planning information, according to the non-profit Urban Institute. A focus group survey suggested that the sex education women received “often lacked substance, leaving them feeling unprepared to make smart decisions about their sexual health and safety,” wrote the authors of the Urban Institute report. In fact, nearly half (45%, or 2.8 million) of the pregnancies that occur each year in the US are unintended, reports the Guttmacher Institute. Globally the numbers are similar. According to a new report by the United Nations, each year there are 121 million unintended pregnancies, worldwide.

The science

The early work on antibodies as a contraceptive had been inspired by women with infertility. It turns out that 9 to 12 percent of women who are treated for infertility have antibodies that develop naturally and work against sperm. Shrestha was encouraged that the antibodies were specific to the target — sperm — and therefore “very safe to use in women.” She aimed to make the antibodies more stable, more effective and less expensive so they could be more easily manufactured.

Since antibodies tend to stick to things that you tell them to stick to, the idea was, basically, to engineer antibodies to stick to sperm so they would stop swimming. Shrestha and her colleagues took the binding arm of an antibody that they’d isolated from an infertile woman. Then, targeting a unique surface antigen present on human sperm, they engineered a panel of antibodies with as many as six to 10 binding arms — “almost like tongs with prongs on the tongs, that bind the sperm,” explains Shrestha. “We decided to add those grabbers on top of it, behind it. So it went from having two prongs to almost 10. And the whole goal was to have so many arms binding the sperm that it clumps it” into a “dollop,” explains Shrestha, who earned a patent on her research.

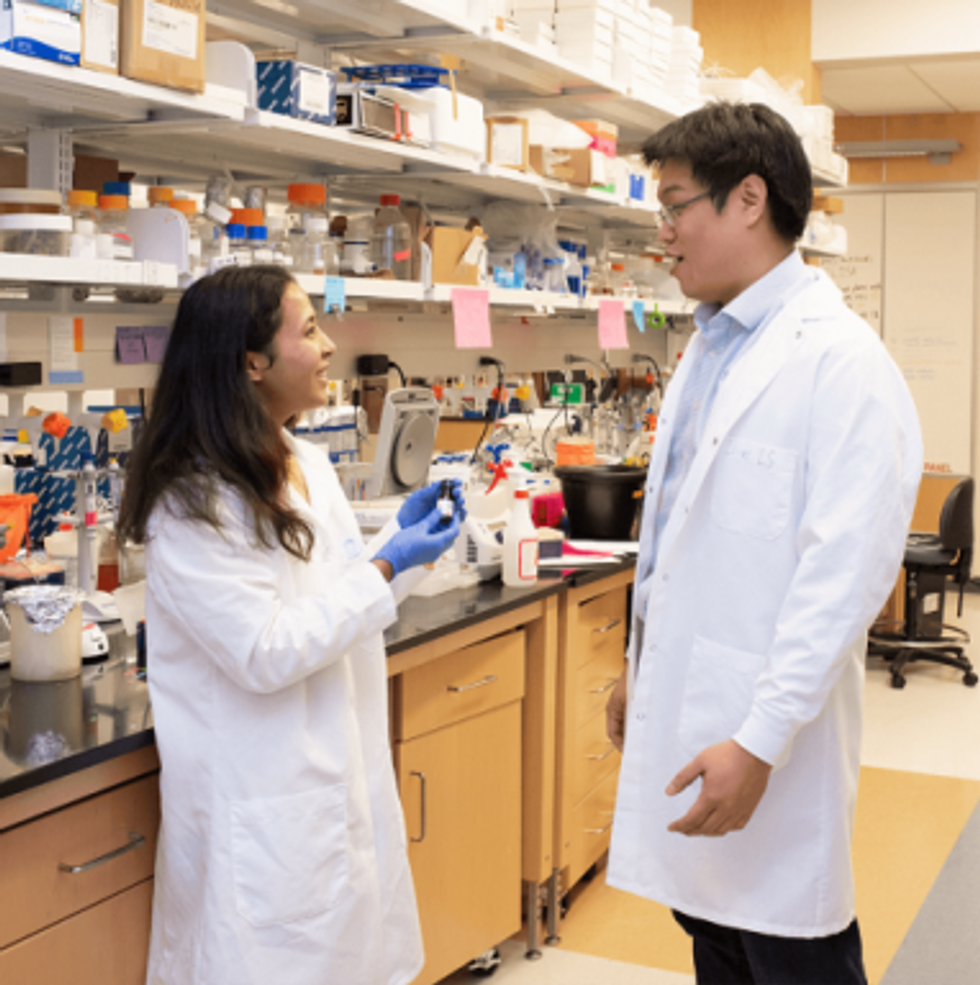

Suruchi Shrestha works in the lab with a colleague. In 2016, her research on antibodies for birth control was inspired by her own experience with side effects from an implanted hormonal IUD.

UNC - Chapel Hill

The sperm stays right where it met the antibody, never reaching the egg for fertilization. Eventually, and naturally, “Our vaginal system will just flush it out,” Shrestha explains.

“She showed in her early studies that [she] definitely got the sperm immotile, so they didn't move. And that was a really promising start,” says Jasmine Edelstein, a scientist with an expertise in antibody engineering who was not involved in this research. Shrestha’s team at UNC reproduced the effect in the sheep, notes Edelstein, who works at the startup Be Biopharma. In fact, Shrestha’s anti-sperm antibodies that caused the sperm to agglutinate, or clump together, were 99.9% effective when delivered topically to the sheep’s reproductive tracts.

The future

Going forward, Shrestha thinks the ideal approach would be delivering the antibodies through a vaginal ring. “We want to use it at the source of the spark,” Shrestha says, as opposed to less direct methods, such as taking a pill. The ring would dissolve after one month, she explains, “and then you get another one.”

Engineered to have a long shelf life, the anti-sperm antibody ring could be purchased without a prescription, and women could insert it themselves, without a doctor. “That's our hope, so that it is accessible,” Shrestha says. “Anybody can just go and grab it and not worry about pregnancy or unintended pregnancy.”

Her patented research has been licensed by several biotech companies for clinical trials. A number of Shrestha’s co-authors, including her lab advisor, Sam Lai, have launched a company, Mucommune, to continue developing the contraceptives based on these antibodies.

And, results from a small clinical trial run by researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine show that a dissolvable vaginal film with antibodies was safe when tested on healthy women of reproductive age. That same group of researchers earlier this year received a $7.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health for further research on monoclonal antibody-based contraceptives, which have also been shown to block transmission of viruses, like HIV.

“As the costs come down, this becomes a more realistic option potentially for women,” says Edelstein. “The impact could be tremendous.”

The Friday Five: An mRNA vaccine works against cancer, new research suggests

In this week's Friday Five, an mRNA vaccine works against cancer for the first time. Plus, these cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power, a new theory for what causes aging, bacteria that could get you excited to work out, and a reason for sex differences in Alzheimer's.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- An mRNA vaccine that works against cancer

- These cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power

- A new theory for what causes aging

- Can bacteria make you excited to work out?

- Why women get Alzheimer's more often than men