How Smallpox Was Wiped Off the Planet By a Vaccine and Global Cooperation

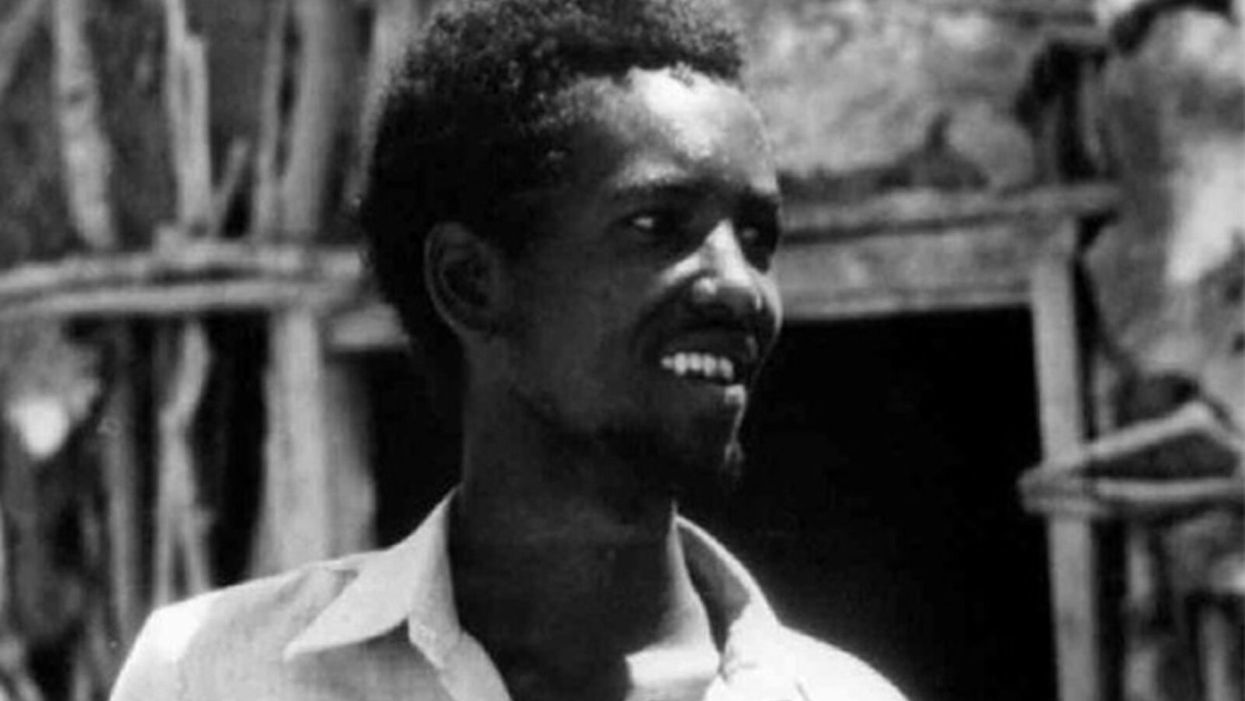

The world's last recorded case of endemic smallpox was in Ali Maow Maalin, of Merka, Somalia, in October 1977. He made a full recovery.

For 3000 years, civilizations all over the world were brutalized by smallpox, an infectious and deadly virus characterized by fever and a rash of painful, oozing sores.

Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success.

Smallpox was merciless, killing one third of people it infected and leaving many survivors permanently pockmarked and blind. Although smallpox was more common during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was still a leading cause of death even up until the early 1950s, killing an estimated 50 million people annually.

A Primitive Cure

Sometime during the 10th century, Chinese physicians figured out that exposing people to a tiny bit of smallpox would sometimes result in a milder infection and immunity to the disease afterward (if the person survived). Desperate for a cure, people would huff powders made of smallpox scabs or insert smallpox pus into their skin, all in the hopes of getting immunity without having to get too sick. However, this method – called inoculation – didn't always work. People could still catch the full-blown disease, spread it to others, or even catch another infectious disease like syphilis in the process.

A Breakthrough Treatment

For centuries, inoculation – however imperfect – was the only protection the world had against smallpox. But in the late 18th century, an English physician named Edward Jenner created a more effective method. Jenner discovered that inoculating a person with cowpox – a much milder relative of the smallpox virus – would make that person immune to smallpox as well, but this time without the possibility of actually catching or transmitting smallpox. His breakthrough became the world's first vaccine against a contagious disease. Other researchers, like Louis Pasteur, would use these same principles to make vaccines for global killers like anthrax and rabies. Vaccination was considered a miracle, conferring all of the rewards of having gotten sick (immunity) without the risk of death or blindness.

Scaling the Cure

As vaccination became more widespread, the number of global smallpox deaths began to drop, particularly in Europe and the United States. But even as late as 1967, smallpox was still killing anywhere from 10 to 15 million people in poorer parts of the globe. The World Health Assembly (a decision-making body of the World Health Organization) decided that year to launch the first coordinated effort to eradicate smallpox from the planet completely, aiming for 80 percent vaccine coverage in every country in which the disease was endemic – a total of 33 countries.

But officials knew that eradicating smallpox would be easier said than done. Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success. The vaccination initiative in Bangladesh proved the most challenging, due to its population density and the prevalence of the disease, writes journalist Laurie Garrett in her book, The Coming Plague.

In one instance, French physician Daniel Tarantola on assignment in Bangladesh confronted a murderous gang that was thought to be spreading smallpox throughout the countryside during their crime sprees. Without police protection, Tarantola confronted the gang and "faced down guns" in order to immunize them, protecting the villagers from repeated outbreaks.

Because not enough vaccines existed to vaccinate everyone in a given country, doctors utilized a strategy called "ring vaccination," which meant locating individual outbreaks and vaccinating all known and possible contacts to stop an outbreak at its source. Fewer than 50 percent of the population in Nigeria received a vaccine, for example, but thanks to ring vaccination, it was eradicated in that country nonetheless. Doctors worked tirelessly for the next eleven years to immunize as many people as possible.

The World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

A Resounding Success

In November 1975, officials discovered a case of variola major — the more virulent strain of the smallpox virus — in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl named Rahima Banu. Banu was forcibly quarantined in her family's home with armed guards until the risk of transmission had passed, while officials went door-to-door vaccinating everyone within a five-mile radius. Two years later, the last case of variola major in human history was reported in Somalia. When no new community-acquired cases appeared after that, the World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

Because of smallpox, we now know it's possible to completely eliminate a disease. But is it likely to happen again with other diseases, like COVID-19? Some scientists aren't so sure. As dangerous as smallpox was, it had a few characteristics that made eradication possibly easier than for other diseases. Smallpox, for instance, has no animal reservoir, meaning that it could not circulate in animals and resurge in a human population at a later date. Additionally, a person who had smallpox once was guaranteed immunity from the disease thereafter — which is not the case for COVID-19.

In The Coming Plague, Japanese physician Isao Arita, who led the WHO's Smallpox Eradication Unit, admitted to routinely defying orders from the WHO, mobilizing to parts of the world without official approval and sometimes even vaccinating people against their will. "If we hadn't broken every single WHO rule many times over, we would have never defeated smallpox," Arita said. "Never."

Still, thanks to the life-saving technology of vaccines – and the tireless efforts of doctors and scientists across the globe – a once-lethal disease is now a thing of the past.

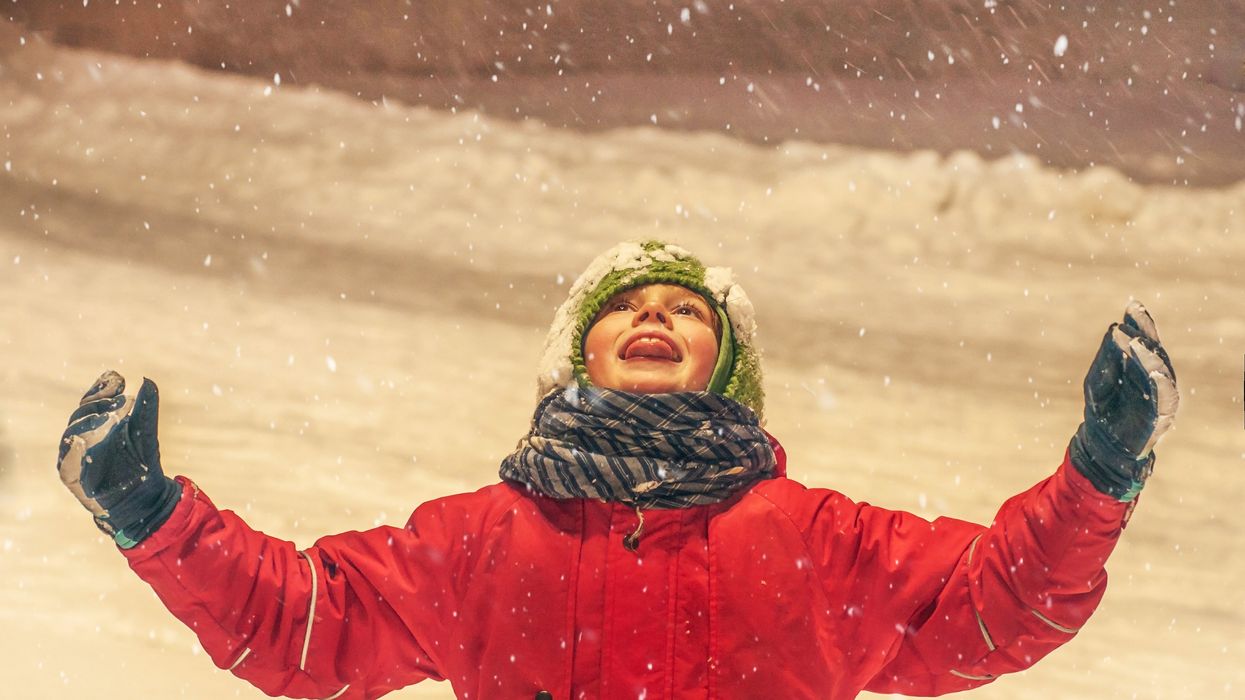

Catching colds may help protect kids from Covid

A new study shows that the immune system's response to colds can help prepare it to defend against COVID-19 - but only in the very young.

A common cold virus causes the immune system to produce T cells that also provide protection against SARS-CoV-2, according to new research. The study, published last month in PNAS, shows that this effect is most pronounced in young children. The finding may help explain why most young people who have been exposed to the cold-causing coronavirus have not developed serious cases of COVID-19.

One curiosity stood out in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic – why were so few kids getting sick. Generally young children and the elderly are the most vulnerable to disease outbreaks, particularly viral infections, either because their immune systems are not fully developed or they are starting to fail.

But solid information on the new infection was so scarce that many public health officials acted on the precautionary principle, assumed a worst-case scenario, and applied the broadest, most restrictive policies to all people to try to contain the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

One early thought was that lockdowns worked and kids (ages 6 months to 17 years) simply were not being exposed to the virus. So it was a shock when data started to come in showing that well over half of them carried antibodies to the virus, indicating exposure without getting sick. That trend grew over time and the latest tracking data from the CDC shows that 96.3 percent of kids in the U.S. now carry those antibodies.

Antibodies are relatively quick and easy to measure, but some scientists are exploring whether the reactions of T cells could serve as a more useful measure of immune protection.

But that couldn't be the whole story because antibody protection fades, sometimes as early as a month after exposure and usually within a year. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 has been spewing out waves of different variants that were more resistant to antibodies generated by their predecessors. The resistance was so significant that over time the FDA withdrew its emergency use authorization for a handful of monoclonal antibodies with earlier approval to treat the infection because they no longer worked.

Antibodies got most of the attention early on because they are part of the first line response of the immune system. Antibodies can bind to viruses and neutralize them, preventing infection. They are relatively quick and easy to measure and even manufacture, but as SARS-CoV-2 showed us, often viruses can quickly evolve to become more resistant to them. Some scientists are exploring whether the reactions of T cells could serve as a more useful measure of immune protection.

Kids, colds and T cells

T cells are part of the immune system that deals with cells once they have become infected. But working with T cells is much more difficult, takes longer, and is more expensive than working with antibodies. So studies often lags behind on this part of the immune system.

A group of researchers led by Annika Karlsson at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden focuses on T cells targeting virus-infected cells and, unsurprisingly, saw that they can play a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Other labs have shown that vaccination and natural exposure to the virus generates different patterns of T cell responses.

The Swedes also looked at another member of the coronavirus family, OC43, which circulates widely and is one of several causes of the common cold. The molecular structure of OC43 is similar to its more deadly cousin SARS-CoV-2. Sometimes a T cell response to one virus can produce a cross-reactive response to a similar protein structure in another virus, meaning that T cells will identify and respond to the two viruses in much the same way. Karlsson looked to see if T cells for OC43 from a wide age range of patients were cross-reactive to SARS-CoV-2.

And that is what they found, as reported in the PNAS study last month; there was cross-reactive activity, but it depended on a person’s age. A subset of a certain type of T cells, called mCD4+,, that recognized various protein parts of the cold-causing virus, OC43, expressed on the surface of an infected cell – also recognized those same protein parts from SARS-CoV-2. The T cell response was lower than that generated by natural exposure to SARS-CoV-2, but it was functional and thus could help limit the severity of COVID-19.

“One of the most politicized aspects of our pandemic response was not accepting that children are so much less at risk for severe disease with COVID-19,” because usually young children are among the most vulnerable to pathogens, says Monica Gandhi, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco.

“The cross-reactivity peaked at age six when more than half the people tested have a cross-reactive immune response,” says Karlsson, though their sample is too small to say if this finding applies more broadly across the population. The vast majority of children as young as two years had OC43-specific mCD4+ T cell responses. In adulthood, the functionality of both the OC43-specific and the cross-reactive T cells wane significantly, especially with advanced age.

“Considering that the mortality rate in children is the lowest from ages five to nine, and higher in younger children, our results imply that cross-reactive mCD4+ T cells may have a role in the control of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children,” the authors wrote in their paper.

“One of the most politicized aspects of our pandemic response was not accepting that children are so much less at risk for severe disease with COVID-19,” because usually young children are among the most vulnerable to pathogens, says Monica Gandhi, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco and author of the book, Endemic: A Post-Pandemic Playbook, to be released by the Mayo Clinic Press this summer. The immune response of kids to SARS-CoV-2 stood our expectations on their head. “We just haven't seen this before, so knowing the mechanism of protection is really important.”

Why the T cell immune response can fade with age is largely unknown. With some viruses such as measles, a single vaccination or infection generates life-long protection. But respiratory tract infections, like SARS-CoV-2, cause a localized infection - specific to certain organs - and that response tends to be shorter lived than systemic infections that affect the entire body. Karlsson suspects the elderly might be exposed to these localized types of viruses less often. Also, frequent continued exposure to a virus that results in reactivation of the memory T cell pool might eventually result in “a kind of immunosenescence or immune exhaustion that is associated with aging,” Karlsson says. https://leaps.org/scientists-just-started-testing-a-new-class-of-drugs-to-slow-and-even-reverse-aging/particle-3 This fading protection is why older people need to be repeatedly vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2.

Policy implications

Following the numbers on COVID-19 infections and severity over the last three years have shown us that healthy young people without risk factors are not likely to develop serious disease. This latest study points to a mechanism that helps explain why. But the inertia of existing policies remains. How should we adjust policy recommendations based on what we know today?

The World Health Organization (WHO) updated their COVID-19 vaccination guidance on March 28. It calls for a focus on vaccinating and boosting those at risk for developing serious disease. The guidance basically shrugged its shoulders when it came to healthy children and young adults receiving vaccinations and boosters against COVID-19. It said the priority should be to administer the “traditional essential vaccines for children,” such as those that protect against measles, rubella, and mumps.

“As an immunologist and a mother, I think that catching a cold or two when you are a kid and otherwise healthy is not that bad for you. Children have a much lower risk of becoming severely ill with SARS-CoV-2,” says Karlsson. She has followed public health guidance in Sweden, which means that her young children have not been vaccinated, but being older, she has received the vaccine and boosters. Gandhi and her children have been vaccinated, but they do not plan on additional boosters.

The WHO got it right in “concentrating on what matters,” which is getting traditional childhood immunizations back on track after their dramatic decline over the last three years, says Gandhi. Nor is there a need for masking in schools, according to a study from the Catalonia region of Spain. It found “no difference in masking and spread in schools,” particularly since tracking data indicate that nearly all young people have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

Both researchers lament that public discussion has overemphasized the quickly fading antibody part of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 compared with the more durable T cell component. They say developing an efficient measure of T cell response for doctors to use in the clinic would help to monitor immunity in people at risk for severe cases of COVID-19 compared with the current method of toting up potential risk factors.

In this week's Friday Five: The eyes are the windows to the soul - and biological aging?

Plus, what bean genes mean for health and the planet, a breathing practice that could lower levels of tau proteins in the brain, AI beats humans at assessing heart health, and the benefits of "nature prescriptions"

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on new scientific theories and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the stories covered this week:

- The eyes are the windows to the soul - and biological aging?

- What bean genes mean for health and the planet

- This breathing practice could lower levels of tau proteins

- AI beats humans at assessing heart health

- Should you get a nature prescription?