Hyperbaric oxygen therapy could treat Long COVID, new study shows

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been used in the past to help people with traumatic brain injury, stroke and other conditions involving wounds to the brain. Now, researchers at Shamir Medical Center in Tel Aviv are studying how it could treat Long Covid.

Long COVID is not a single disease, it is a syndrome or cluster of symptoms that can arise from exposure to SARS-CoV-2, a virus that affects an unusually large number of different tissue types. That's because the ACE2 receptor it uses to enter cells is common throughout the body, and inflammation from the immune response fighting that infection can damage surrounding tissue.

One of the most widely shared groups of symptoms is fatigue and what has come to be called “brain fog,” a difficulty focusing and an amorphous feeling of slowed mental functioning and capacity. Researchers have tied these COVID-related symptoms to tissue damage in specific sections of the brain and actual shrinkage in its size.

When Shai Efrati, medical director of the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research in Tel Aviv, first looked at functional magnetic resonance images (fMRIs) of patients with what is now called long COVID, he saw “micro infarcts along the brain.” It reminded him of similar lesions in other conditions he had treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). “Once we saw that, we said, this is the type of wound we can treat. It doesn't matter if the primary cause is mechanical injury like TBI [traumatic brain injury] or stroke … we know how to oxidize them.”Efrati came to HBOT almost by accident. The physician had seen how it had helped heal diabetic ulcers and improved the lives of other patients, but he was busy with his own research. Then the director of his Tel Aviv hospital threatened to shut down the small HBOT chamber unless Efrati took on administrative responsibility for it. He reluctantly agreed, a decision that shifted the entire focus of his research.

“The main difference between wounds in the leg and wounds in the brain is that one is something we can see, it's tangible, and the wound in the brain is hidden,” says Efrati. With fMRIs, he can measure how a limited supply of oxygen in blood is shuttled around to fuel activity in various parts of the brain. Years of research have mapped how specific areas of the brain control activity ranging from thinking to moving. An fMRI captures the brain area as it’s activated by supplies of oxygen; lack of activity after the same stimuli suggests damage has occurred in that tissue. Suddenly, what was hidden became visible to researchers using fMRI. It helped to make a diagnosis and measure response to treatment.

HBOT is not a single thing but rather a tool, a process or approach with variations depending on the condition being treated. It aims to increase the amount of oxygen that gets to damaged tissue and speed up healing. Regular air is about 21 percent oxygen. But inside the HBOT chamber the atmospheric pressure can be increased to up to three times normal pressure at sea level and the patient breathes pure oxygen through a mask; blood becomes saturated with much higher levels of oxygen. This can defuse through the damaged capillaries of a wound and promote healing.

The trial

Efrati’s clinical trials started in December 2020, barely a year after SARS-CoV-2 had first appeared in Israel. Patients who’d experienced cognitive issues after having COVID received 40 sessions in the chamber over a period of 60 days. In each session, they spent 90 minutes breathing through a mask at two atmospheres of pressure. While inside, they performed mental exercises to train the brain. The only difference between the two groups of patients was that one breathed pure oxygen while the other group breathed normal air. No one knew who was receiving which level of oxygen.

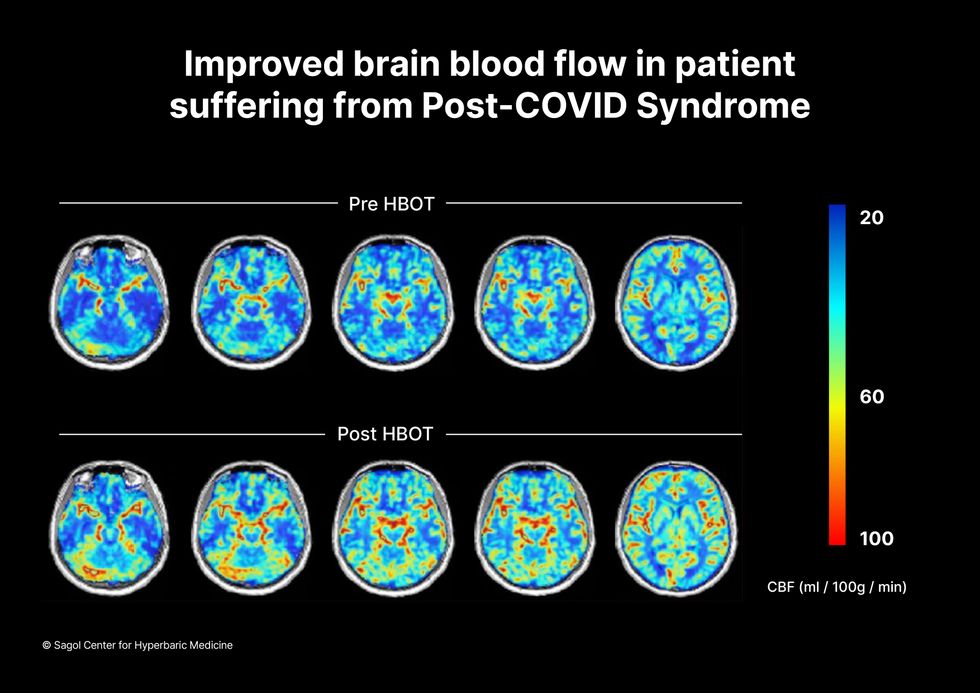

The results were striking. Before and after fMRIs showed significant repair of damaged tissue in the brain and functional cognition tests improved substantially among those who received pure oxygen. Importantly, 80 percent of patients said they felt back to “normal,” but Efrati says they didn't include patient evaluation in the paper because there was no baseline data to show how they functioned before COVID. After the study was completed, the placebo group was offered a new round of treatments using 100 percent oxygen, and the team saw similar results.

Scans show improved blood flow in a patient suffering from Long Covid.

Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine

Efrati's use of HBOT is part of an emerging geroscience approach to diseases associated with aging. These researchers see systems dysfunctions that are common to several diseases, such as inflammation, which has been shown to play a role in micro infarcts, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Preliminary research suggests that HBOT can retard some underlying mechanisms of aging, which might address several medical conditions. However, the drug approval process is set up to regulate individual disease, not conditions as broad as aging, and so they concentrate on treating the low hanging fruit: disorders where effective treatments currently are limited and success might be demonstrated.

The key to HBOT's effectiveness is something called the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox where a body does not react to an increase in available oxygen, only to a decrease, regardless of the starting point. That danger signal has a powerful effect on gene expression, resulting in changes in metabolism, and the proliferation of stem cells. That occurs with each cycle of 20 minutes of pure oxygen followed by 5 minutes of regular air circulating through the masks, while the chamber remains pressurized. The high levels of oxygen in the blood provide the fuel necessary for tissue regeneration.

The hyperbaric chamber that Efrati has built can hold a dozen patients and attending medical staff. Think of it as a pressurized airplane cabin, only with much more space than even in first class. In the U.S., people think of HBOT as “a sack of air or some tube that you can buy on Amazon” or find at a health spa. “That is total bullshit,” Efrati says. “It has to be a medical class center where a physician can lose their license if they are not operating it properly.”

Shai Efrati

Alexander Charney, a research psychiatrist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, calls Efrati’s study thoughtful and well designed. But it demands a lot from patients with its intense number of sessions. Those types of regimens have proven difficult to roll out to large numbers of patients. Still, the results are intriguing enough to merit additional trials.

John J. Miller, a physician and editor in chief of Psychiatric Times, has seen “many physicians that use hyperbaric oxygen for various brain disorders such as TBI.” He is intrigued by Efrati's work and believes the approach “has great potential to help patients with long COVID whose symptoms are related to brain tissue changes.”

Efrati believes so much in the power of the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox to heal a variety of tissue injuries that he is leading the medical advisory board at Aviv Clinic, an international network of clinics that are delivering HBOT treatments based on research conducted in Israel. His goal is to silence doubters by quickly opening about 50 such clinics worldwide, based on the model of standalone dialysis clinics in the United States. Sagol Center is treating 300 patients per day, and clinics have opened in Florida and Dubai. There are plans to open another in Manhattan.

Did researchers finally find a way to lick COVID?

A professor of medicine at the University of Michigan is researching whether lactoferrin, which is found in dairy products such as ice cream, can help to prevent COVID-19 infections.

Already vaccinated and want more protection from COVID-19? A protein found in ice cream could help, some research suggests, though there are a bunch of caveats.

The protein, called lactoferrin, is found in the milk of mammals and thus in dairy products, including ice cream. It has astounding antiviral properties that have been taken for granted and remain largely unexplored because it is a natural product, meaning that it cannot be patented and exploited by pharmaceutical companies.

Still, a few researchers in Europe and elsewhere have sought to better understand the compound.

Jonathan Sexton runs a drug screening program at the University of Michigan where cells are infected with a pathogen and then exposed to a library of the thousands of small molecule drug compounds – which can enter the body more easily than drugs with heavier molecules – approved by the FDA. In addition, the library includes compounds that passed phase 1 safety studies but later proved ineffective against the targeted disease. Each drug is dissolved in a solvent for exposure to the cells in the laborious testing process made feasible by robotic automation.

When COVID hit, researchers scrambled to identify any approved drug that might help fight the infection. Sexton decided to screen the drug library as well as some dietary supplements against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease. Sexton says that the grunt work fell to Jesse Wotring, “a very talented PhD student,” who pulled lactoferrin off the shelf. But the regular solvent used in the testing process would destroy the protein, so he had to take another approach and do all the work by hand.

“We were agnostic,” says Sexton, who didn't have a strong interest in lactoferrin or any of the other compounds in the library, but the data was quite clear; lactoferrin “consistently produced the best efficacy...it was the absolute home run.” The findings were published in separate papers last year and in February.

It turns out that lactoferrin has several different mechanisms of action against SARS-CoV-2, inhibiting the virus from entering cells, moving around within them and replicating. Lactoferrin also modulates the overall immune response, which makes it difficult for the virus to simultaneously mutate resistance to the protein at every step of replication. “It has broad efficacy against every [SARS-CoV-2] variant that we've tested,” he says.

From bench to bedside

Sexton's initial interest was to develop a drug for the acute phase of COVID infection, to treat a hospitalized patient or prevent that hospitalization. But with the quick approval of vaccines and drugs to treat the disease, he increasingly focused on ways to better prevent infection and inhibit spread of the virus.

“If you can get lactoferrin to persist in your upper GI tract, then it may very well prevent the primary infection, and that's what we're really interested in.” He reasoned that a chewing gum formula might release enough lactoferrin into the mucosal tissue of the mouth and upper airways to inhibit replication and give the immune system a chance to knock out the virus before it can establish a foothold. It could also reduce the amount of virus spread through talking.

To get enough lactoferrin to have a possible beneficial effect, one would have to drink gallons of milk a day, “and that would have other undesirable consequences, like getting extremely obese,” says Sexton. Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for severe COVID disease.

Testing that theory has been difficult. The easiest way would be a “challenge trial,” where volunteers take the drug, or in this case gum, are exposed to the pathogen, and protection is measured. Some COVID challenge studies have been conducted in Europe but the FDA remains hesitant to allow such a study in the U.S. A traditional prevention study would be like a vaccine trial, involving thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of volunteers over a period of months or years, and it would be very expensive. No one has stepped forward to foot the bill.

So the next step for Sexton is a clinical trial of newly diagnosed COVID patients who will be given standard of care treatment, and layered on top of that they will receive either lactoferrin, probably in pill form, or a placebo. He has identified initial funding. “We would study their viral load over time as well as their symptoms.”

One issue the FDA is grappling with in considering the proposed trial is that it typically decides whether to approve drugs from a factory by applying a rigorous standard, called good manufacturing practices, while food products, which are the source of lactoferrin, are produced under somewhat different standards. The agency still has not finalized rules on how to deal with natural products used as drugs, such as fecal transplants, convalescent plasma, or medical marijuana.

Sexton is frustrated by the delay because lactoferrin derived from bovine milk whey has been used for many decades as a protein supplement by athletes, it is a large component of most infant formula, and the largest number of clinical studies of lactoferrin involve premature infants. There is no question of its safety, he says.

Do it yourself

So what can you do while waiting for regulatory wheels to spin and clinical trial data to be generated?

Could a dose of Ben & Jerry's provide some protection against SARS-CoV-2?

Sexton chuckles at the suggestion. He supposes it couldn't hurt. But to get enough lactoferrin to have a possible beneficial effect, one would have to drink gallons of milk a day, “and that would have other undesirable consequences, like getting extremely obese.” Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for severe COVID disease.

Pseudo-milk products made from soy, almonds, oats, or other plant products do not contain lactoferrin; it has to come from a teat. So that rules them out.

Whey-based protein shakes might be a useful way to add lactoferrin to the diet.

Probably the best option is to take conventional gelatin capsules of lactoferrin that are widely available wherever supplements are sold. Sexton calculates that about a gram a day, four 250 milligram capsules, should do it. He advises two in the morning and two a night. “You really want to take them on an empty stomach...your stomach treats [the lactoferrin protein] like it would a steak” and chops it for absorption in the intestine, which you do not want. About 70 percent of lactoferrin can get through an empty stomach, but eating food cranks up digestive gastric acids and the amount of intact lactoferrin that gets through to the gut plummets.

Sexton cautions, “We have not determined clinical efficacy yet,” and he is not offering advice as a physician, but in the spirit of harm reduction, he realizes that some people are going to try things that might help them. Lactoferrin “is remarkably safe. And so people have to make their own decisions about what they are willing to take and what they are not,” he says.

In today's episode, Leaps.org interviews Camila dos Santos, a molecular biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, about her research on breasts and what makes them unique compared to any other part of the body.

My guest today for the Making Sense of Science podcast is Camila dos Santos, associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, who is a leading researcher of the inner lives of human mammary glands, more commonly known as breasts. These organs are unlike any other because throughout life they undergo numerous changes, first in puberty, then during pregnancies and lactation periods, and finally at the end of the cycle, when babies are weaned. A complex interplay of hormones governs these processes, in some cases increasing the risk of breast cancer and sometimes lowering it. Witnessing the molecular mechanics behind these processes in humans is not possible, so instead Dos Santos studies organoids—the clumps of breast cells donated by patients who undergo breast reduction surgeries or biopsies.

Show notes:

2:52 In response to hormones that arise during puberty, the breast cells grow and become more specialized, preparing the tissue for making milk.

7:53 How do breast cells know when to produce milk? It’s all governed by chemical messaging in the body. When the baby is born, the brain will release the hormone called oxytocin, which will make the breast cells contract and release the milk.

12:40 Breast resident immune cells are including T-cells and B-cells, but because they live inside the breast tissue their functions differ from the immune cells in other parts of the body,

17:00 With organoids—dimensional clumps of cells that are cultured in a dish—it is possible to visualize and study how these cells produce milk.

21:50 Women who are pregnant later in life are more likely to require medical intervention to breastfeed. Scientists are trying to understand the fundamental reasons why it happens.

26:10 Breast cancer has many risks factors. Generic mutations play a big role. All of us have the BRCA genes, but it is the alternation in the DNA sequence of the BRCA gene that can increase the predisposition to breast cancer. Aging and menopause are the risk factors for breast cancer, and so are pregnancies.

29:22 Women that are pregnant before the age of 20 to 25, have a decreased risk of breast cancer. And the hypothesis here is that during pregnancy breast cells more specialized, as specialized cells, they have a limited lifespan. It's more likely that they die before they turn into cancer.

33:08 Organoids are giving scientists an opportunity to practice personalized medicine. Scientists can test drugs on organoids taken from a patient to identify the most efficient treatment protocol.

Links:

Camila dos Santos’s Lab Page.

Editor's note: In addition to being a regular writer for Leaps.org, Lina Zeldovich is the guest host for today's episode of the Making Sense of Science podcast.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.