Is China Winning the Innovation Race?

Flags of America and China illuminated by light bulbs with a question mark between them.

Over the past two millennia, Chinese ingenuity has spawned some of humanity's most consequential inventions. Without gunpowder, guns, bombs, and rockets; without paper, printing, and money printed on paper; and without the compass, which enabled ships to navigate the open ocean, modern civilization might never have been born.

Today, a specter is haunting the developed world: Chinese innovation dominance. And the results have been so spectacular that the United States feels its preeminence threatened.

Yet China lapsed into cultural and technological stagnation during the Qing dynasty, just as the Scientific Revolution was transforming Europe. Western colonial incursions and a series of failed rebellions further sapped the Celestial Empire's capacity for innovation. By the mid-20th century, when the Communist triumph led to a devastating famine and years of bloody political turmoil, practically the only intellectual property China could offer for export was Mao's Little Red Book.

After Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, launching a transition from a rigidly planned economy to a semi-capitalist one, China's factories began pumping out goods for foreign consumption. Still, originality remained a low priority. The phrase "Made in China" came to be synonymous with "cheap knockoff."

Today, however, a specter is haunting the developed world: Chinese innovation dominance. It first wafted into view in 2006, when the government announced an "indigenous innovation" campaign, dedicated to establishing China as a technology powerhouse by 2020—and a global leader by 2050—as part of its Medium- and Long-Term National Plan for Science and Technology Development. Since then, an array of initiatives have sought to unleash what pundits often call the Chinese "tech dragon," whether in individual industries, such as semiconductors or artificial intelligence, or across the board (as with the Made in China 2025 project, inaugurated in 2015). These efforts draw on a well-stocked bureaucratic arsenal: state-directed financing; strategic mergers and acquisitions; competition policies designed to boost domestic companies and hobble foreign rivals; buy-Chinese procurement policies; cash incentives for companies to file patents; subsidies for academic researchers in favored fields.

The results have been spectacular—so much so that the United States feels its preeminence threatened. Voices across the political spectrum are calling for emergency measures, including a clampdown on technology transfers, capital investment, and Chinese students' ability to study abroad. But are the fears driving such proposals justified?

"We've flipped from thinking China is incapable of anything but imitation to thinking China is about to eat our lunch," says Kaiser Kuo, host of the Sinica podcast at supchina.com, who recently returned to the U.S after 20 years in Beijing—the last six as director of international communications for the tech giant Baidu. Like some other veteran China-watchers, Kuo believes neither extreme reflects reality. "We're in as much danger now of overestimating China's innovative capacity," he warns, "as we were a few years ago of underestimating it."

A Lab and Tech-Business Bonanza

By many measures, China's innovation renaissance is mind-boggling. Spending on research and development as a percentage of gross domestic product nearly quadrupled between 1996 and 2016, from .56 percent to 2.1 percent; during the same period, spending in the United States rose by just .3 percentage points, from 2.44 to 2.79 percent of GDP. China is now second only to the U.S. in total R&D spending, accounting for 21 percent of the global total of $2 trillion, according to a report released in January by the National Science Foundation. In 2016, the number of scientific publications from China exceeded those from the U.S. for the first time, by 426,000 to 409,000. Chinese researchers are blazing new trails on the frontiers of cloning, stem cell medicine, gene editing, and quantum computing. Chinese patent applications have soared from 170,000 to nearly 3 million since 2000; the country now files almost as many international patents as the U.S. and Japan, and more than Germany and South Korea. Between 2008 and 2017, two Chinese tech firms—Huawei and ZTE—traded places as the world's top patent filer in six out of nine years.

"China is still in its Star Trek phase, while we're in our Black Mirror phase." Yet there are formidable barriers to China beating America in the innovation race—or even catching up anytime soon.

Accompanying this lab-based ferment is a tech-business bonanza. China's three biggest internet companies, Baidu, Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings (known collectively as BAT), have become global titans of search, e-commerce, mobile payments, gaming, and social media. Da-Jiang Innovations in Science and Technology (DJI) controls more than 70 percent of the world's commercial drone market. Of the planet's 262 "unicorns" (startups worth more than a billion dollars), about one-third are Chinese. The country attracted $77 billion in venture capital investment between 2014 and 2016, according to Fortune, and is now among the top three markets for VC in emerging technologies including AI, virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, and 3D printing.

These developments have fueled a buoyant techno-optimism in China that contrasts sharply with the darker view increasingly prevalent in the West—in part, perhaps, because China's historic limits on civil liberties have inured the populace to the intrusive implications of, say, facial recognition technology or social-credit software, which are already being used to tighten government control. "China is still in its Star Trek phase, while we're in our Black Mirror phase," Kuo observes. By contrast with Americans' ambivalent attitudes toward Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg or Amazon's Jeff Bezos, he adds, most Chinese regard tech entrepreneurs like Baidu's Robin Li and Alibaba's Jack Ma as "flat-out heroes."

Yet there are formidable barriers to China beating America in the innovation race—or even catching up anytime soon. Many are catalogued in The Fat Tech Dragon, a 2017 monograph by Scott Kennedy, deputy director of the Freeman Chair in China Studies and director of the Project on Chinese Business and Political Economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Among the obstacles, Kennedy writes, are "an education system that encourages deference to authority and does not prepare students to be creative and take risks, a financial system that disproportionately funnels funds to undeserving state-owned enterprises… and a market structure where profits can be made through a low-margin, high-volume strategy or through political connections."

China's R&D money, Kennedy points out, is mostly showered on the "D": of the $209 billion spent in 2015, only 5 percent went toward basic research, 10.8 percent toward applied research, and a massive 84.2 percent toward development. While fully half of venture capital in the States goes to early-stage startups, the figure for China is under 20 percent; true "angel" investors are scarce. Likewise, only 21 percent of Chinese patents are for original inventions, as opposed to tweaks of existing technologies. Most problematic, the domestic value of patents in China is strikingly low. In 2015, the country's patent licensing generated revenues of just $1.75 billion, compared to $115 billion for IP licensing in the U.S. in 2012 (the most recent year for which data is available). In short, Kennedy concludes, "China may now be a 'large' IP country, but it is still a 'weak' one."

"[The Chinese] are trying very hard to keep the economy from crashing, but it'll happen eventually. Then there will be a major, major contraction."

Anne Stevenson-Yang, co-founder and research director of J Capital Research, and a leading China analyst, sees another potential stumbling block: the government's obsession with neck-snapping GDP growth. "What China does is to determine, 'Our GDP growth will be X,' and then it generates enough investment to create X," Stevenson-Yang explains. To meet those quotas, officials pour money into gigantic construction projects, creating the empty "ghost cities" that litter the countryside, or subsidize industrial production far beyond realistic demand. "It's the ultimate Ponzi-scheme economy," she says, citing as examples the Chinese cellphone and solar industries, which ballooned on state funding, flooded global markets with dirt-cheap products, thrived just long enough to kill off most of their overseas competitors, and then largely collapsed. Such ventures, Stevenson-Yang notes, have driven China's debt load perilously high. "They're trying very hard to keep the economy from crashing, but it'll happen eventually," she predicts. "Then there will be a major, major contraction."

"An Intensifying Race Toward Techno-Nationalism"

The greatest vulnerability of the Chinese innovation boom may be that it still depends heavily on imported IP. "Over the last few years, China has placed its bets on a combination of global knowledge sourcing and indigenous technology development," says Dieter Ernst, a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation in Waterloo, Canada, and the East-West Center in Honolulu, who has served as an Asia advisor for the U.N. and the World Bank. Aside from international journals (and, occasionally, industrial espionage), Chinese labs and corporations obtain non-indigenous knowledge in a number of ways: by paying licensing fees; recruiting Chinese scientists and engineers who've studied or worked abroad; hiring professionals from other countries; or acquiring foreign companies. And though enforcement of IP laws has improved markedly in recent years, foreign businesses are often pressured to provide technology transfers in exchange for access to markets.

Many of China's top tech entrepreneurs—including Ma, Li, and Alibaba's Joseph Tsai—are alumni of U.S. universities, and, as Kuo puts it, "big fans of all things American." Unfortunately, however, Americans are ever less likely to be fans of China, thanks largely to that country's sometimes predatory trade practices—and also to what Ernst calls "an intensifying race toward techno-nationalism." With varying degrees of bellicosity and consistency, leaders of both U.S. parties embrace elements of the trend, as do politicians (and voters) across much of Europe. "There's a growing consensus that China is poised to overtake us," says Ernst, "and that we need to design policies to obstruct its rise."

One of the foremost liberal analysts supporting this view is Lee Branstetter, a professor of economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University and former senior economist on President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisors. "Over the decades, in a systematic and premeditated fashion, the Chinese government and its state-owned enterprises have worked to extract valuable technology from foreign multinationals, with an explicit goal of eventually displacing those leading multinationals with successful Chinese firms in global markets," Branstetter wrote in a 2017 report to the United States Trade Representative. To combat such "forced transfers," he suggested, laws could be passed empowering foreign governments to investigate coercive requests and block any deemed inappropriate—not just those involving military-related or crucial infrastructure technology, which current statutes cover. Branstetter also called for "sharply" curtailing Chinese students' access to Western graduate programs, as a way to "get policymakers' attention in Beijing" and induce them to play fair.

Similar sentiments are taking hold in Congress, where the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act—aimed at strengthening the process by which the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States reviews Chinese acquisition of American technologies—is expected to pass with bipartisan support, though its harsher provisions were softened due to objections from Silicon Valley. The Trump Administration announced in May that it would soon take executive action to curb Chinese investments in U.S. tech firms and otherwise limit access to intellectual property. The State Department, meanwhile, imposed a one-year limit on visas for Chinese grad students in high-tech fields.

Ernst argues that such measures are motivated largely by exaggerated notions of China's ability to reach its ambitious goals, and by the political advantages that fearmongering confers. "If you look at AI, chip design and fabrication, robotics, pharmaceuticals, the gap with the U.S. is huge," he says. "Reducing it will take at least 10 or 15 years."

Cracking down on U.S. tech transfers to Chinese companies, Ernst cautions, will deprive U.S. firms of vital investment capital and spur China to retaliate, cutting off access to the nation's gargantuan markets; it will also push China to forge IP deals with more compliant nations, or revert to outright piracy. And restricting student visas, besides harming U.S. universities that depend on Chinese scholars' billions in tuition, will have a "chilling effect on America's ability to attract to researchers and engineers from all countries."

"It's not a zero-sum game. I don't think China is going to eat our lunch. We can sit down and enjoy lunch together."

America's own science and technology community, Ernst adds, considers it crucial to swap ideas with China's fast-growing pool of talent. The 2017 annual meeting of the Palo Alto-based Association for Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, he notes, featured a nearly equal number of papers by researchers in China and the U.S. Organizers postponed the meeting after discovering that the original date coincided with the Chinese New Year.

China's rising influence on the tech world carries upsides as well as downsides, Scott Kennedy observes. The country's successes in e-commerce, he says, "haven't damaged the global internet sector, but have actually been a spur to additional innovation and progress. By contrast, China's success in solar and wind has decimated the global sectors," due to state-mandated overcapacity. "When Chinese firms win through open competition, the outcome is constructive; when they win through industrial policy and protectionism, the outcome is destructive."

The solution, Kennedy and like-minded experts argue, is to discourage protectionism rather than engage in it, adjusting tech-transfer policy just enough to cope with evolving national-security concerns. Instead of trying to squelch China's innovation explosion, they say, the U.S. should seek ways to spread its potential benefits (as happened in previous eras with Japan and South Korea), and increase America's indigenous investments in tech-related research, education, and job training.

"It's not a zero-sum game," says Kaiser Kuo. "I don't think China is going to eat our lunch. We can sit down and enjoy lunch together."

Nobel Prize goes to technology for mRNA vaccines

Katalin Karikó, pictured, and Drew Weissman won the Nobel Prize for advances in mRNA research that led to the first Covid vaccines.

When Drew Weissman received a call from Katalin Karikó in the early morning hours this past Monday, he assumed his longtime research partner was calling to share a nascent, nagging idea. Weissman, a professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and Karikó, a professor at Szeged University and an adjunct professor at UPenn, both struggle with sleep disturbances. Thus, middle-of-the-night discourses between the two, often over email, has been a staple of their friendship. But this time, Karikó had something more pressing and exciting to share: They had won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

The work for which they garnered the illustrious award and its accompanying $1,000,000 cash windfall was completed about two decades ago, wrought through long hours in the lab over many arduous years. But humanity collectively benefited from its life-saving outcome three years ago, when both Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccines against COVID were found to be safe and highly effective at preventing severe disease. Billions of doses have since been given out to protect humans from the upstart viral scourge.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” said Katalin Karikó. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

Unlocking the power of mRNA

Weissman and Karikó unlocked mRNA vaccines for the world back in the early 2000s when they made a key breakthrough. Messenger RNA molecules are essentially instructions for cells’ ribosomes to make specific proteins, so in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers started wondering if sneaking mRNA into the body could trigger cells to manufacture antibodies, enzymes, or growth agents for protecting against infection, treating disease, or repairing tissues. But there was a big problem: injecting this synthetic mRNA triggered a dangerous, inflammatory immune response resulting in the mRNA’s destruction.

While most other researchers chose not to tackle this perplexing problem to instead pursue more lucrative and publishable exploits, Karikó stuck with it. The choice sent her academic career into depressing doldrums. Nobody would fund her work, publications dried up, and after six years as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó got demoted. She was going backward.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” Karikó told Stat in 2020. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

A tale of tenacity

Collaborating with Drew Weissman, a new professor at the University of Pennsylvania, in the late 1990s helped provide Karikó with the tenacity to continue. Weissman nurtured a goal of developing a vaccine against HIV-1, and saw mRNA as a potential way to do it.

“For the 20 years that we’ve worked together before anybody knew what RNA is, or cared, it was the two of us literally side by side at a bench working together,” Weissman said in an interview with Adam Smith of the Nobel Foundation.

In 2005, the duo made their 2023 Nobel Prize-winning breakthrough, detailing it in a relatively small journal, Immunity. (Their paper was rejected by larger journals, including Science and Nature.) They figured out that chemically modifying the nucleoside bases that make up mRNA allowed the molecule to slip past the body’s immune defenses. Karikó and Weissman followed up that finding by creating mRNA that’s more efficiently translated within cells, greatly boosting protein production. In 2020, scientists at Moderna and BioNTech (where Karikó worked from 2013 to 2022) rushed to craft vaccines against COVID, putting their methods to life-saving use.

The future of vaccines

Buoyed by the resounding success of mRNA vaccines, scientists are now hurriedly researching ways to use mRNA medicine against other infectious diseases, cancer, and genetic disorders. The now ubiquitous efforts stand in stark contrast to Karikó and Weissman’s previously unheralded struggles years ago as they doggedly worked to realize a shared dream that so many others shied away from. Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman were brave enough to walk a scientific path that very well could have ended in a dead end, and for that, they absolutely deserve their 2023 Nobel Prize.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Scientists turn pee into power in Uganda

With conventional fuel cells as their model, researchers learned to use similar chemical reactions to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

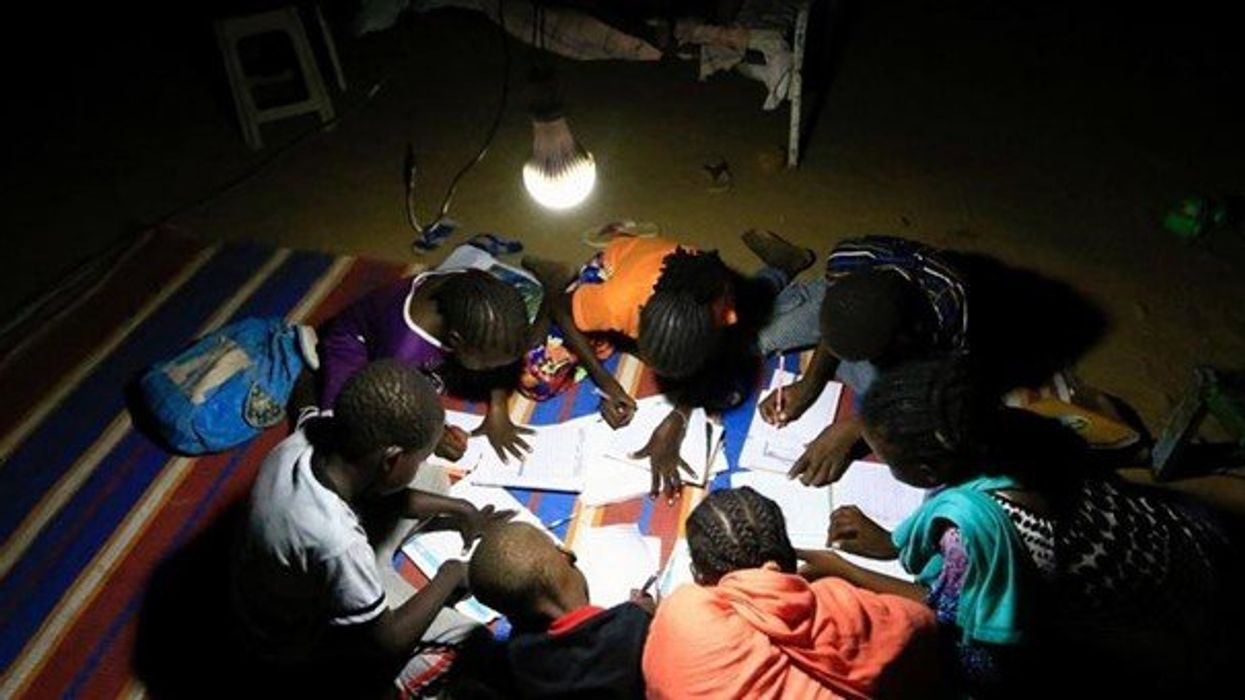

At the edge of a dirt road flanked by trees and green mountains outside the town of Kisoro, Uganda, sits the concrete building that houses Sesame Girls School, where girls aged 11 to 19 can live, learn and, at least for a while, safely use a toilet. In many developing regions, toileting at night is especially dangerous for children. Without electrical power for lighting, kids may fall into the deep pits of the latrines through broken or unsteady floorboards. Girls are sometimes assaulted by men who hide in the dark.

For the Sesame School girls, though, bright LED lights, connected to tiny gadgets, chased the fears away. They got to use new, clean toilets lit by the power of their own pee. Some girls even used the light provided by the latrines to study.

Urine, whether animal or human, is more than waste. It’s a cheap and abundant resource. Each day across the globe, 8.1 billion humans make 4 billion gallons of pee. Cows, pigs, deer, elephants and other animals add more. By spending money to get rid of it, we waste a renewable resource that can serve more than one purpose. Microorganisms that feed on nutrients in urine can be used in a microbial fuel cell that generates electricity – or "pee power," as the Sesame girls called it.

Plus, urine contains water, phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen, the key ingredients plants need to grow and survive. Human urine could replace about 25 percent of current nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers worldwide and could save water for gardens and crops. The average U.S. resident flushes a toilet bowl containing only pee and paper about six to seven times a day, which adds up to about 3,500 gallons of water down per year. Plus cows in the U.S. produce 231 gallons of the stuff each year.

Pee power

A conventional fuel cell uses chemical reactions to produce energy, as electrons move from one electrode to another to power a lightbulb or phone. Ioannis Ieropoulos, a professor and chair of Environmental Engineering at the University of Southampton in England, realized the same type of reaction could be used to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

Bacterial species like Shewanella oneidensis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa can consume carbon and other nutrients in urine and pop out electrons as a result of their digestion. In a microbial fuel cell, one electrode is covered in microbes, immersed in urine and kept away from oxygen. Another electrode is in contact with oxygen. When the microbes feed on nutrients, they produce the electrons that flow through the circuit from one electrod to another to combine with oxygen on the other side. As long as the microbes have fresh pee to chomp on, electrons keep flowing. And after the microbes are done with the pee, it can be used as fertilizer.

These microbes are easily found in wastewater treatment plants, ponds, lakes, rivers or soil. Keeping them alive is the easy part, says Ieropoulos. Once the cells start producing stable power, his group sequences the microbes and keeps using them.

Like many promising technologies, scaling these devices for mass consumption won’t be easy, says Kevin Orner, a civil engineering professor at West Virginia University. But it’s moving in the right direction. Ieropoulos’s device has shrunk from the size of about three packs of cards to a large glue stick. It looks and works much like a AAA battery and produce about the same power. By itself, the device can barely power a light bulb, but when stacked together, they can do much more—just like photovoltaic cells in solar panels. His lab has produced 1760 fuel cells stacked together, and with manufacturing support, there’s no theoretical ceiling, he says.

Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofit into urban wastewater utilities.

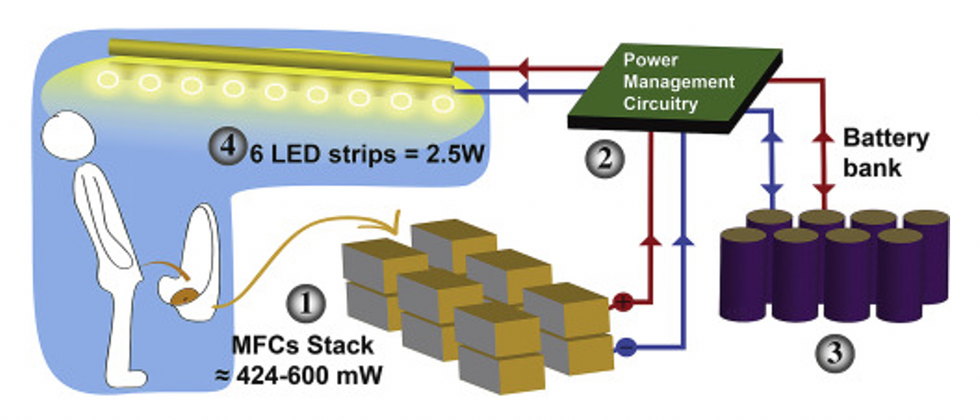

This image shows how the pee-powered system works. Pee feeds bacteria in the stack of fuel cells (1), which give off electrons (2) stored in parallel cylindrical cells (3). These cells are connected to a voltage regulator (4), which smooths out the electrical signal to ensure consistent power to the LED strips lighting the toilet.

Courtesy Ioannis Ieropoulos

Key to the long-term success of any urine reclamation effort, says Orner, is avoiding what he calls “parachute engineering”—when well-meaning scientists solve a problem with novel tech and then abandon it. “The way around that is to have either the need come from the community or to have an organization in a community that is committed to seeing a project operate and maintained,” he says.

Success with urine reclamation also depends on the economy. “If energy prices are low, it may not make sense to recover energy,” says Orner. “But right now, fertilizer prices worldwide are generally pretty high, so it may make sense to recover fertilizer and nutrients.” There are obstacles, too, such as few incentives for builders to incorporate urine recycling into new construction. And any hiccups like leaks or waste seepage will cost builders money and reputation. Right now, Orner says, the risks are just too high.

Despite the challenges, Ieropoulos envisions a future in which urine is passed through microbial fuel cells at wastewater treatment plants, retrofitted septic tanks, and building basements, and is then delivered to businesses to use as agricultural fertilizers. Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofitted into urban wastewater utilities where they can make electricity from the effluent. And unlike solar cells, which are a common target of theft in some areas, nobody wants to steal a bunch of pee.

When Ieropoulos’s team returned to wrap up their pilot project 18 months later, the school’s director begged them to leave the fuel cells in place—because they made a major difference in students’ lives. “We replaced it with a substantial photovoltaic panel,” says Ieropoulos, They couldn’t leave the units forever, he explained, because of intellectual property reasons—their funders worried about theft of both the technology and the idea. But the photovoltaic replacement could be stolen, too, leaving the girls in the dark.

The story repeated itself at another school, in Nairobi, Kenya, as well as in an informal settlement in Durban, South Africa. Each time, Ieropoulos vowed to return. Though the pandemic has delayed his promise, he is resolute about continuing his work—it is a moral and legal obligation. “We've made a commitment to ourselves and to the pupils,” he says. “That's why we need to go back.”

Urine as fertilizer

Modern day industrial systems perpetuate the broken cycle of nutrients. When plants grow, they use up nutrients the soil. We eat the plans and excrete some of the nutrients we pass them into rivers and oceans. As a result, farmers must keep fertilizing the fields while our waste keeps fertilizing the waterways, where the algae, overfertilized with nitrogen, phosphorous and other nutrients grows out of control, sucking up oxygen that other marine species need to live. Few global communities remain untouched by the related challenges this broken chain create: insufficient clean water, food, and energy, and too much human and animal waste.

The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont runs a community-wide urine nutrient recovery program, which collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms.

One solution to this broken cycle is reclaiming urine and returning it back to the land. The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont is one of several organizations around the world working to divert and save urine for agricultural use. “The urine produced by an adult in one day contains enough fertilizer to grow all the wheat in one loaf of bread,” states their website.

Notably, while urine is not entirely sterile, it tends to harbor fewer pathogens than feces. That’s largely because urine has less organic matter and therefore less food for pathogens to feed on, but also because the urinary tract and the bladder have built-in antimicrobial defenses that kill many germs. In fact, the Rich Earth Institute says it’s safe to put your own urine onto crops grown for home consumption. Nonetheless, you’ll want to dilute it first because pee usually has too much nitrogen and can cause “fertilizer burn” if applied straight without dilution. Other projects to turn urine into fertilizer are in progress in Niger, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sweden, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Australia, and France.

Eleven years ago, the Institute started a program that collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms. By 2021, the program included 180 donors producing over 12,000 gallons of urine each year. This urine is helping to fertilize hay fields at four partnering farms. Orner, the West Virginia professor, sees it as a success story. “They've shown how you can do this right--implementing it at a community level scale."