Is China Winning the Innovation Race?

Flags of America and China illuminated by light bulbs with a question mark between them.

Over the past two millennia, Chinese ingenuity has spawned some of humanity's most consequential inventions. Without gunpowder, guns, bombs, and rockets; without paper, printing, and money printed on paper; and without the compass, which enabled ships to navigate the open ocean, modern civilization might never have been born.

Today, a specter is haunting the developed world: Chinese innovation dominance. And the results have been so spectacular that the United States feels its preeminence threatened.

Yet China lapsed into cultural and technological stagnation during the Qing dynasty, just as the Scientific Revolution was transforming Europe. Western colonial incursions and a series of failed rebellions further sapped the Celestial Empire's capacity for innovation. By the mid-20th century, when the Communist triumph led to a devastating famine and years of bloody political turmoil, practically the only intellectual property China could offer for export was Mao's Little Red Book.

After Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, launching a transition from a rigidly planned economy to a semi-capitalist one, China's factories began pumping out goods for foreign consumption. Still, originality remained a low priority. The phrase "Made in China" came to be synonymous with "cheap knockoff."

Today, however, a specter is haunting the developed world: Chinese innovation dominance. It first wafted into view in 2006, when the government announced an "indigenous innovation" campaign, dedicated to establishing China as a technology powerhouse by 2020—and a global leader by 2050—as part of its Medium- and Long-Term National Plan for Science and Technology Development. Since then, an array of initiatives have sought to unleash what pundits often call the Chinese "tech dragon," whether in individual industries, such as semiconductors or artificial intelligence, or across the board (as with the Made in China 2025 project, inaugurated in 2015). These efforts draw on a well-stocked bureaucratic arsenal: state-directed financing; strategic mergers and acquisitions; competition policies designed to boost domestic companies and hobble foreign rivals; buy-Chinese procurement policies; cash incentives for companies to file patents; subsidies for academic researchers in favored fields.

The results have been spectacular—so much so that the United States feels its preeminence threatened. Voices across the political spectrum are calling for emergency measures, including a clampdown on technology transfers, capital investment, and Chinese students' ability to study abroad. But are the fears driving such proposals justified?

"We've flipped from thinking China is incapable of anything but imitation to thinking China is about to eat our lunch," says Kaiser Kuo, host of the Sinica podcast at supchina.com, who recently returned to the U.S after 20 years in Beijing—the last six as director of international communications for the tech giant Baidu. Like some other veteran China-watchers, Kuo believes neither extreme reflects reality. "We're in as much danger now of overestimating China's innovative capacity," he warns, "as we were a few years ago of underestimating it."

A Lab and Tech-Business Bonanza

By many measures, China's innovation renaissance is mind-boggling. Spending on research and development as a percentage of gross domestic product nearly quadrupled between 1996 and 2016, from .56 percent to 2.1 percent; during the same period, spending in the United States rose by just .3 percentage points, from 2.44 to 2.79 percent of GDP. China is now second only to the U.S. in total R&D spending, accounting for 21 percent of the global total of $2 trillion, according to a report released in January by the National Science Foundation. In 2016, the number of scientific publications from China exceeded those from the U.S. for the first time, by 426,000 to 409,000. Chinese researchers are blazing new trails on the frontiers of cloning, stem cell medicine, gene editing, and quantum computing. Chinese patent applications have soared from 170,000 to nearly 3 million since 2000; the country now files almost as many international patents as the U.S. and Japan, and more than Germany and South Korea. Between 2008 and 2017, two Chinese tech firms—Huawei and ZTE—traded places as the world's top patent filer in six out of nine years.

"China is still in its Star Trek phase, while we're in our Black Mirror phase." Yet there are formidable barriers to China beating America in the innovation race—or even catching up anytime soon.

Accompanying this lab-based ferment is a tech-business bonanza. China's three biggest internet companies, Baidu, Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings (known collectively as BAT), have become global titans of search, e-commerce, mobile payments, gaming, and social media. Da-Jiang Innovations in Science and Technology (DJI) controls more than 70 percent of the world's commercial drone market. Of the planet's 262 "unicorns" (startups worth more than a billion dollars), about one-third are Chinese. The country attracted $77 billion in venture capital investment between 2014 and 2016, according to Fortune, and is now among the top three markets for VC in emerging technologies including AI, virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, and 3D printing.

These developments have fueled a buoyant techno-optimism in China that contrasts sharply with the darker view increasingly prevalent in the West—in part, perhaps, because China's historic limits on civil liberties have inured the populace to the intrusive implications of, say, facial recognition technology or social-credit software, which are already being used to tighten government control. "China is still in its Star Trek phase, while we're in our Black Mirror phase," Kuo observes. By contrast with Americans' ambivalent attitudes toward Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg or Amazon's Jeff Bezos, he adds, most Chinese regard tech entrepreneurs like Baidu's Robin Li and Alibaba's Jack Ma as "flat-out heroes."

Yet there are formidable barriers to China beating America in the innovation race—or even catching up anytime soon. Many are catalogued in The Fat Tech Dragon, a 2017 monograph by Scott Kennedy, deputy director of the Freeman Chair in China Studies and director of the Project on Chinese Business and Political Economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Among the obstacles, Kennedy writes, are "an education system that encourages deference to authority and does not prepare students to be creative and take risks, a financial system that disproportionately funnels funds to undeserving state-owned enterprises… and a market structure where profits can be made through a low-margin, high-volume strategy or through political connections."

China's R&D money, Kennedy points out, is mostly showered on the "D": of the $209 billion spent in 2015, only 5 percent went toward basic research, 10.8 percent toward applied research, and a massive 84.2 percent toward development. While fully half of venture capital in the States goes to early-stage startups, the figure for China is under 20 percent; true "angel" investors are scarce. Likewise, only 21 percent of Chinese patents are for original inventions, as opposed to tweaks of existing technologies. Most problematic, the domestic value of patents in China is strikingly low. In 2015, the country's patent licensing generated revenues of just $1.75 billion, compared to $115 billion for IP licensing in the U.S. in 2012 (the most recent year for which data is available). In short, Kennedy concludes, "China may now be a 'large' IP country, but it is still a 'weak' one."

"[The Chinese] are trying very hard to keep the economy from crashing, but it'll happen eventually. Then there will be a major, major contraction."

Anne Stevenson-Yang, co-founder and research director of J Capital Research, and a leading China analyst, sees another potential stumbling block: the government's obsession with neck-snapping GDP growth. "What China does is to determine, 'Our GDP growth will be X,' and then it generates enough investment to create X," Stevenson-Yang explains. To meet those quotas, officials pour money into gigantic construction projects, creating the empty "ghost cities" that litter the countryside, or subsidize industrial production far beyond realistic demand. "It's the ultimate Ponzi-scheme economy," she says, citing as examples the Chinese cellphone and solar industries, which ballooned on state funding, flooded global markets with dirt-cheap products, thrived just long enough to kill off most of their overseas competitors, and then largely collapsed. Such ventures, Stevenson-Yang notes, have driven China's debt load perilously high. "They're trying very hard to keep the economy from crashing, but it'll happen eventually," she predicts. "Then there will be a major, major contraction."

"An Intensifying Race Toward Techno-Nationalism"

The greatest vulnerability of the Chinese innovation boom may be that it still depends heavily on imported IP. "Over the last few years, China has placed its bets on a combination of global knowledge sourcing and indigenous technology development," says Dieter Ernst, a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation in Waterloo, Canada, and the East-West Center in Honolulu, who has served as an Asia advisor for the U.N. and the World Bank. Aside from international journals (and, occasionally, industrial espionage), Chinese labs and corporations obtain non-indigenous knowledge in a number of ways: by paying licensing fees; recruiting Chinese scientists and engineers who've studied or worked abroad; hiring professionals from other countries; or acquiring foreign companies. And though enforcement of IP laws has improved markedly in recent years, foreign businesses are often pressured to provide technology transfers in exchange for access to markets.

Many of China's top tech entrepreneurs—including Ma, Li, and Alibaba's Joseph Tsai—are alumni of U.S. universities, and, as Kuo puts it, "big fans of all things American." Unfortunately, however, Americans are ever less likely to be fans of China, thanks largely to that country's sometimes predatory trade practices—and also to what Ernst calls "an intensifying race toward techno-nationalism." With varying degrees of bellicosity and consistency, leaders of both U.S. parties embrace elements of the trend, as do politicians (and voters) across much of Europe. "There's a growing consensus that China is poised to overtake us," says Ernst, "and that we need to design policies to obstruct its rise."

One of the foremost liberal analysts supporting this view is Lee Branstetter, a professor of economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University and former senior economist on President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisors. "Over the decades, in a systematic and premeditated fashion, the Chinese government and its state-owned enterprises have worked to extract valuable technology from foreign multinationals, with an explicit goal of eventually displacing those leading multinationals with successful Chinese firms in global markets," Branstetter wrote in a 2017 report to the United States Trade Representative. To combat such "forced transfers," he suggested, laws could be passed empowering foreign governments to investigate coercive requests and block any deemed inappropriate—not just those involving military-related or crucial infrastructure technology, which current statutes cover. Branstetter also called for "sharply" curtailing Chinese students' access to Western graduate programs, as a way to "get policymakers' attention in Beijing" and induce them to play fair.

Similar sentiments are taking hold in Congress, where the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act—aimed at strengthening the process by which the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States reviews Chinese acquisition of American technologies—is expected to pass with bipartisan support, though its harsher provisions were softened due to objections from Silicon Valley. The Trump Administration announced in May that it would soon take executive action to curb Chinese investments in U.S. tech firms and otherwise limit access to intellectual property. The State Department, meanwhile, imposed a one-year limit on visas for Chinese grad students in high-tech fields.

Ernst argues that such measures are motivated largely by exaggerated notions of China's ability to reach its ambitious goals, and by the political advantages that fearmongering confers. "If you look at AI, chip design and fabrication, robotics, pharmaceuticals, the gap with the U.S. is huge," he says. "Reducing it will take at least 10 or 15 years."

Cracking down on U.S. tech transfers to Chinese companies, Ernst cautions, will deprive U.S. firms of vital investment capital and spur China to retaliate, cutting off access to the nation's gargantuan markets; it will also push China to forge IP deals with more compliant nations, or revert to outright piracy. And restricting student visas, besides harming U.S. universities that depend on Chinese scholars' billions in tuition, will have a "chilling effect on America's ability to attract to researchers and engineers from all countries."

"It's not a zero-sum game. I don't think China is going to eat our lunch. We can sit down and enjoy lunch together."

America's own science and technology community, Ernst adds, considers it crucial to swap ideas with China's fast-growing pool of talent. The 2017 annual meeting of the Palo Alto-based Association for Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, he notes, featured a nearly equal number of papers by researchers in China and the U.S. Organizers postponed the meeting after discovering that the original date coincided with the Chinese New Year.

China's rising influence on the tech world carries upsides as well as downsides, Scott Kennedy observes. The country's successes in e-commerce, he says, "haven't damaged the global internet sector, but have actually been a spur to additional innovation and progress. By contrast, China's success in solar and wind has decimated the global sectors," due to state-mandated overcapacity. "When Chinese firms win through open competition, the outcome is constructive; when they win through industrial policy and protectionism, the outcome is destructive."

The solution, Kennedy and like-minded experts argue, is to discourage protectionism rather than engage in it, adjusting tech-transfer policy just enough to cope with evolving national-security concerns. Instead of trying to squelch China's innovation explosion, they say, the U.S. should seek ways to spread its potential benefits (as happened in previous eras with Japan and South Korea), and increase America's indigenous investments in tech-related research, education, and job training.

"It's not a zero-sum game," says Kaiser Kuo. "I don't think China is going to eat our lunch. We can sit down and enjoy lunch together."

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

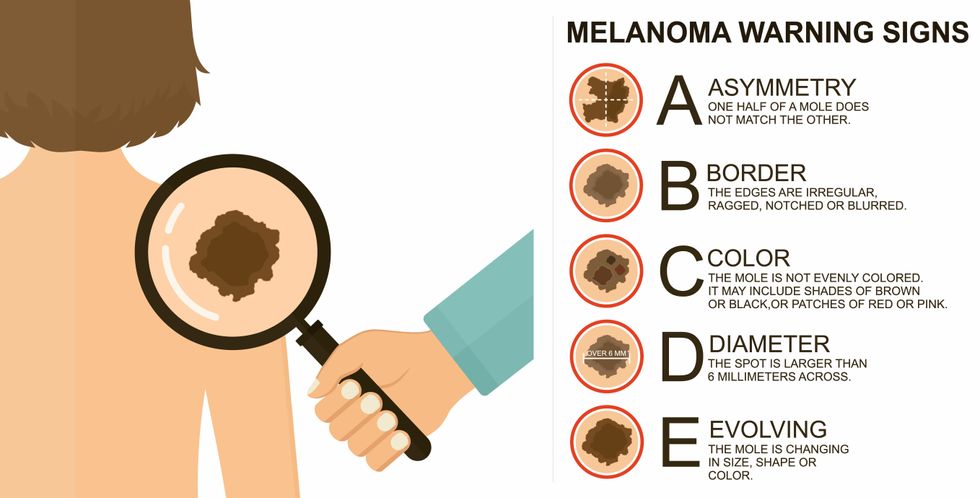

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.