Is China Winning the Innovation Race?

Flags of America and China illuminated by light bulbs with a question mark between them.

Over the past two millennia, Chinese ingenuity has spawned some of humanity's most consequential inventions. Without gunpowder, guns, bombs, and rockets; without paper, printing, and money printed on paper; and without the compass, which enabled ships to navigate the open ocean, modern civilization might never have been born.

Today, a specter is haunting the developed world: Chinese innovation dominance. And the results have been so spectacular that the United States feels its preeminence threatened.

Yet China lapsed into cultural and technological stagnation during the Qing dynasty, just as the Scientific Revolution was transforming Europe. Western colonial incursions and a series of failed rebellions further sapped the Celestial Empire's capacity for innovation. By the mid-20th century, when the Communist triumph led to a devastating famine and years of bloody political turmoil, practically the only intellectual property China could offer for export was Mao's Little Red Book.

After Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, launching a transition from a rigidly planned economy to a semi-capitalist one, China's factories began pumping out goods for foreign consumption. Still, originality remained a low priority. The phrase "Made in China" came to be synonymous with "cheap knockoff."

Today, however, a specter is haunting the developed world: Chinese innovation dominance. It first wafted into view in 2006, when the government announced an "indigenous innovation" campaign, dedicated to establishing China as a technology powerhouse by 2020—and a global leader by 2050—as part of its Medium- and Long-Term National Plan for Science and Technology Development. Since then, an array of initiatives have sought to unleash what pundits often call the Chinese "tech dragon," whether in individual industries, such as semiconductors or artificial intelligence, or across the board (as with the Made in China 2025 project, inaugurated in 2015). These efforts draw on a well-stocked bureaucratic arsenal: state-directed financing; strategic mergers and acquisitions; competition policies designed to boost domestic companies and hobble foreign rivals; buy-Chinese procurement policies; cash incentives for companies to file patents; subsidies for academic researchers in favored fields.

The results have been spectacular—so much so that the United States feels its preeminence threatened. Voices across the political spectrum are calling for emergency measures, including a clampdown on technology transfers, capital investment, and Chinese students' ability to study abroad. But are the fears driving such proposals justified?

"We've flipped from thinking China is incapable of anything but imitation to thinking China is about to eat our lunch," says Kaiser Kuo, host of the Sinica podcast at supchina.com, who recently returned to the U.S after 20 years in Beijing—the last six as director of international communications for the tech giant Baidu. Like some other veteran China-watchers, Kuo believes neither extreme reflects reality. "We're in as much danger now of overestimating China's innovative capacity," he warns, "as we were a few years ago of underestimating it."

A Lab and Tech-Business Bonanza

By many measures, China's innovation renaissance is mind-boggling. Spending on research and development as a percentage of gross domestic product nearly quadrupled between 1996 and 2016, from .56 percent to 2.1 percent; during the same period, spending in the United States rose by just .3 percentage points, from 2.44 to 2.79 percent of GDP. China is now second only to the U.S. in total R&D spending, accounting for 21 percent of the global total of $2 trillion, according to a report released in January by the National Science Foundation. In 2016, the number of scientific publications from China exceeded those from the U.S. for the first time, by 426,000 to 409,000. Chinese researchers are blazing new trails on the frontiers of cloning, stem cell medicine, gene editing, and quantum computing. Chinese patent applications have soared from 170,000 to nearly 3 million since 2000; the country now files almost as many international patents as the U.S. and Japan, and more than Germany and South Korea. Between 2008 and 2017, two Chinese tech firms—Huawei and ZTE—traded places as the world's top patent filer in six out of nine years.

"China is still in its Star Trek phase, while we're in our Black Mirror phase." Yet there are formidable barriers to China beating America in the innovation race—or even catching up anytime soon.

Accompanying this lab-based ferment is a tech-business bonanza. China's three biggest internet companies, Baidu, Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings (known collectively as BAT), have become global titans of search, e-commerce, mobile payments, gaming, and social media. Da-Jiang Innovations in Science and Technology (DJI) controls more than 70 percent of the world's commercial drone market. Of the planet's 262 "unicorns" (startups worth more than a billion dollars), about one-third are Chinese. The country attracted $77 billion in venture capital investment between 2014 and 2016, according to Fortune, and is now among the top three markets for VC in emerging technologies including AI, virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, and 3D printing.

These developments have fueled a buoyant techno-optimism in China that contrasts sharply with the darker view increasingly prevalent in the West—in part, perhaps, because China's historic limits on civil liberties have inured the populace to the intrusive implications of, say, facial recognition technology or social-credit software, which are already being used to tighten government control. "China is still in its Star Trek phase, while we're in our Black Mirror phase," Kuo observes. By contrast with Americans' ambivalent attitudes toward Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg or Amazon's Jeff Bezos, he adds, most Chinese regard tech entrepreneurs like Baidu's Robin Li and Alibaba's Jack Ma as "flat-out heroes."

Yet there are formidable barriers to China beating America in the innovation race—or even catching up anytime soon. Many are catalogued in The Fat Tech Dragon, a 2017 monograph by Scott Kennedy, deputy director of the Freeman Chair in China Studies and director of the Project on Chinese Business and Political Economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Among the obstacles, Kennedy writes, are "an education system that encourages deference to authority and does not prepare students to be creative and take risks, a financial system that disproportionately funnels funds to undeserving state-owned enterprises… and a market structure where profits can be made through a low-margin, high-volume strategy or through political connections."

China's R&D money, Kennedy points out, is mostly showered on the "D": of the $209 billion spent in 2015, only 5 percent went toward basic research, 10.8 percent toward applied research, and a massive 84.2 percent toward development. While fully half of venture capital in the States goes to early-stage startups, the figure for China is under 20 percent; true "angel" investors are scarce. Likewise, only 21 percent of Chinese patents are for original inventions, as opposed to tweaks of existing technologies. Most problematic, the domestic value of patents in China is strikingly low. In 2015, the country's patent licensing generated revenues of just $1.75 billion, compared to $115 billion for IP licensing in the U.S. in 2012 (the most recent year for which data is available). In short, Kennedy concludes, "China may now be a 'large' IP country, but it is still a 'weak' one."

"[The Chinese] are trying very hard to keep the economy from crashing, but it'll happen eventually. Then there will be a major, major contraction."

Anne Stevenson-Yang, co-founder and research director of J Capital Research, and a leading China analyst, sees another potential stumbling block: the government's obsession with neck-snapping GDP growth. "What China does is to determine, 'Our GDP growth will be X,' and then it generates enough investment to create X," Stevenson-Yang explains. To meet those quotas, officials pour money into gigantic construction projects, creating the empty "ghost cities" that litter the countryside, or subsidize industrial production far beyond realistic demand. "It's the ultimate Ponzi-scheme economy," she says, citing as examples the Chinese cellphone and solar industries, which ballooned on state funding, flooded global markets with dirt-cheap products, thrived just long enough to kill off most of their overseas competitors, and then largely collapsed. Such ventures, Stevenson-Yang notes, have driven China's debt load perilously high. "They're trying very hard to keep the economy from crashing, but it'll happen eventually," she predicts. "Then there will be a major, major contraction."

"An Intensifying Race Toward Techno-Nationalism"

The greatest vulnerability of the Chinese innovation boom may be that it still depends heavily on imported IP. "Over the last few years, China has placed its bets on a combination of global knowledge sourcing and indigenous technology development," says Dieter Ernst, a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation in Waterloo, Canada, and the East-West Center in Honolulu, who has served as an Asia advisor for the U.N. and the World Bank. Aside from international journals (and, occasionally, industrial espionage), Chinese labs and corporations obtain non-indigenous knowledge in a number of ways: by paying licensing fees; recruiting Chinese scientists and engineers who've studied or worked abroad; hiring professionals from other countries; or acquiring foreign companies. And though enforcement of IP laws has improved markedly in recent years, foreign businesses are often pressured to provide technology transfers in exchange for access to markets.

Many of China's top tech entrepreneurs—including Ma, Li, and Alibaba's Joseph Tsai—are alumni of U.S. universities, and, as Kuo puts it, "big fans of all things American." Unfortunately, however, Americans are ever less likely to be fans of China, thanks largely to that country's sometimes predatory trade practices—and also to what Ernst calls "an intensifying race toward techno-nationalism." With varying degrees of bellicosity and consistency, leaders of both U.S. parties embrace elements of the trend, as do politicians (and voters) across much of Europe. "There's a growing consensus that China is poised to overtake us," says Ernst, "and that we need to design policies to obstruct its rise."

One of the foremost liberal analysts supporting this view is Lee Branstetter, a professor of economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University and former senior economist on President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisors. "Over the decades, in a systematic and premeditated fashion, the Chinese government and its state-owned enterprises have worked to extract valuable technology from foreign multinationals, with an explicit goal of eventually displacing those leading multinationals with successful Chinese firms in global markets," Branstetter wrote in a 2017 report to the United States Trade Representative. To combat such "forced transfers," he suggested, laws could be passed empowering foreign governments to investigate coercive requests and block any deemed inappropriate—not just those involving military-related or crucial infrastructure technology, which current statutes cover. Branstetter also called for "sharply" curtailing Chinese students' access to Western graduate programs, as a way to "get policymakers' attention in Beijing" and induce them to play fair.

Similar sentiments are taking hold in Congress, where the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act—aimed at strengthening the process by which the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States reviews Chinese acquisition of American technologies—is expected to pass with bipartisan support, though its harsher provisions were softened due to objections from Silicon Valley. The Trump Administration announced in May that it would soon take executive action to curb Chinese investments in U.S. tech firms and otherwise limit access to intellectual property. The State Department, meanwhile, imposed a one-year limit on visas for Chinese grad students in high-tech fields.

Ernst argues that such measures are motivated largely by exaggerated notions of China's ability to reach its ambitious goals, and by the political advantages that fearmongering confers. "If you look at AI, chip design and fabrication, robotics, pharmaceuticals, the gap with the U.S. is huge," he says. "Reducing it will take at least 10 or 15 years."

Cracking down on U.S. tech transfers to Chinese companies, Ernst cautions, will deprive U.S. firms of vital investment capital and spur China to retaliate, cutting off access to the nation's gargantuan markets; it will also push China to forge IP deals with more compliant nations, or revert to outright piracy. And restricting student visas, besides harming U.S. universities that depend on Chinese scholars' billions in tuition, will have a "chilling effect on America's ability to attract to researchers and engineers from all countries."

"It's not a zero-sum game. I don't think China is going to eat our lunch. We can sit down and enjoy lunch together."

America's own science and technology community, Ernst adds, considers it crucial to swap ideas with China's fast-growing pool of talent. The 2017 annual meeting of the Palo Alto-based Association for Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, he notes, featured a nearly equal number of papers by researchers in China and the U.S. Organizers postponed the meeting after discovering that the original date coincided with the Chinese New Year.

China's rising influence on the tech world carries upsides as well as downsides, Scott Kennedy observes. The country's successes in e-commerce, he says, "haven't damaged the global internet sector, but have actually been a spur to additional innovation and progress. By contrast, China's success in solar and wind has decimated the global sectors," due to state-mandated overcapacity. "When Chinese firms win through open competition, the outcome is constructive; when they win through industrial policy and protectionism, the outcome is destructive."

The solution, Kennedy and like-minded experts argue, is to discourage protectionism rather than engage in it, adjusting tech-transfer policy just enough to cope with evolving national-security concerns. Instead of trying to squelch China's innovation explosion, they say, the U.S. should seek ways to spread its potential benefits (as happened in previous eras with Japan and South Korea), and increase America's indigenous investments in tech-related research, education, and job training.

"It's not a zero-sum game," says Kaiser Kuo. "I don't think China is going to eat our lunch. We can sit down and enjoy lunch together."

New Options Are Emerging in the Search for Better Birth Control

Photo by JPC-PROD on Adobe Stock

About decade ago, Elizabeth Summers' options for birth control suddenly narrowed. Doctors diagnosed her with Factor V Leiden, a rare genetic disorder, after discovering blood clots in her lungs. The condition increases the risk of clotting, so physicians told Summers to stay away from the pill and other hormone-laden contraceptives. "Modern medicine has generally failed to provide me with an effective and convenient option," she says.

But new birth control options are emerging for women like Summers. These alternatives promise to provide more choices to women who can't ingest hormones or don't want to suffer their unpleasant side effects.

These new products have their own pros and cons. Still, doctors are welcoming new contraceptives following a long drought in innovation. "It's been a long time since we've had something new in the world of contraception," says Heather Irobunda, an obstetrician and gynecologist at NYC Health and Hospitals.

On social media, Irobunda often fields questions about one of these new options, a lubricating gel called Phexxi. San Diego-based Evofem, the company behind Phexxi, has been advertising the product on Hulu and Instagram after the gel was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2020. The company's trendy ads target women who feel like condoms diminish the mood, but who also don't want to mess with an IUD or hormones.

Here's how it works: Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex. The gel regulates vaginal pH — essentially, the acidity levels — in a range that's inhospitable to sperm. It sounds a lot like spermicide, which is also placed in the vagina prior to sex to prevent pregnancy. But spermicide can damage the vagina's cell walls, which can increase the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

"Not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option."

Phexxi isn't without side effects either. The most common one is vaginal burning, according to a late-stage trial. It's also possible to develop a urinary tract infection while using the product. That same study found that during typical use, Phexxi is about 86 percent effective at preventing pregnancy. The efficacy rate is comparable to condoms but lower than birth control pills (91 percent) and significantly lower than an IUD (99 percent).

Phexxi – which comes in a pack of 12 – represents a tiny but growing part of the birth control market. Pharmacies dispensed more than 14,800 packs from April through June this year, a 65 percent increase over the previous quarter, according to data from Evofem.

"We've been able to demonstrate that not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option," says Saundra Pelletier, Evofem's CEO.

Beyond contraception, the company is carrying out late-stage tests to gauge Phexxi's effectiveness at preventing the sexually transmitted infections chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex.

Phexxi

A New Pill

The first birth control pill arrived in 1960, combining the hormones estrogen and progestin to stop sperm from joining with an egg, giving women control over their fertility. Subsequent formulations sought to ease side effects, by way of lower amounts of estrogen. But some women still experience headaches and nausea – or more serious complications like blood clots. On social media, women noted that birth control pills are much more likely to cause blood clots than Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine that was briefly paused to evaluate the risk of clots in women under age 50. What will it take, they wondered, for safer birth control?

Mithra Pharmaceuticals of Belgium sought to create a gentler pill. In April 2021, the FDA approved Mithra's Nextstellis, which includes a naturally occurring estrogen, the first new estrogen in the U.S. in 50 years. Nextstellis selectively acts on tissues lining the uterus, while other birth control pills have a broader target.

A Phase 3 trial showed a 98 percent efficacy rate. Andrew London, an obstetrician and gynecologist, who practices at several Maryland hospitals, says the results are in line with some other birth control pills. But, he added, early studies indicate that Nextstellis has a lower risk of blood clotting, along with other potential benefits, which additional clinical testing must confirm.

"It's not going to be worse than any other pill. We're hoping it's going to be significantly better," says London.

The estrogen in Nexstellis, called estetrol, was skipped over by the pharmaceutical industry after its discovery in the 1960s. Estetrol circulates between the mother and fetus during pregnancy. Decades later, researchers took a new look, after figuring out how to synthesize estetrol in a lab, as well as produce estetrol from plants.

"That allowed us to really start to investigate the properties and do all this stuff you have to do for any new drug," says Michele Gordon, vice president of marketing in women's health at Mayne Pharma, which licensed Nextstellis.

Bonnie Douglas, who followed the development of Nextstellis as part of a search for better birth control, recently switched to the product. "So far, it's much more tolerable," says Douglas. Previously, the Midwesterner was so desperate to find a contraceptive with fewer side effects that she turned to an online pharmacy to obtain a different birth control pill that had been approved in Canada but not in the U.S.

Contraceptive Access

Even if a contraceptive lands FDA approval, access poses a barrier. Getting insurers to cover new contraceptives can be difficult. For the uninsured, state and federal programs can help, and companies should keep prices in a reasonable range, while offering assistance programs. So says Kelly Blanchard, president of the nonprofit Ibis Reproductive Health. "For innovation to have impact, you want to reach as many folks as possible," she says.

In addition, companies developing new contraceptives have struggled to attract venture capital. That's changing, though.

In 2015, Sabrina Johnson founded DARÉ Bioscience around the idea of women's health. She estimated the company would be fully funded in six months, based on her track record in biotech and the demand for novel products.

But it's been difficult to get male investors interested in backing new contraceptives. It took Johnson two and a half years to raise the needed funds, via a reverse merger that took the company public. "There was so much education that was necessary," Johnson says, adding: "The landscape has changed considerably."

Johnson says she would like to think DARÉ had something to do with the shift, along with companies like Organon, a spinout of pharma company Merck that's focused on reproductive health. In surveying the fertility landscape, DARÉ saw limited non-hormonal options. On-demand options – like condoms – can detract from the moment. Copper IUDs must be inserted by a doctor and removed if a woman wants to return to fertility, and this method can have onerous side effects.

So, DARÉ created Ovaprene, a hormone-free device that's designed to be inserted into the vagina monthly by the user. The mesh product acts as a barrier, while releasing a chemical that immobilizes sperm. In an early study, the company reported that Ovaprene prevented almost all sperm from entering the cervical canal. The results, DARÉ believes, indicate high efficacy. Should Ovaprene eventually win regulatory approval, drug giant Bayer will handle commercializing the device.

Other new forms of birth control in development are further out, and that's assuming they perform well in clinical trials. Among them: a once-a-month birth control pill, along with a male version of the birth control pill. The latter is often brought up among women who say it's high time that men take a more proactive role in birth control.

For Summers, her search for a safe and convenient birth control continues. She tried Phexxi, which caused irritation. Still, she's excited that a non-hormonal option now exists. "I'm sure it will work for others," she says.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on August 31, 2021.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy could treat Long COVID, new study shows

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been used in the past to help people with traumatic brain injury, stroke and other conditions involving wounds to the brain. Now, researchers at Shamir Medical Center in Tel Aviv are studying how it could treat Long Covid.

Long COVID is not a single disease, it is a syndrome or cluster of symptoms that can arise from exposure to SARS-CoV-2, a virus that affects an unusually large number of different tissue types. That's because the ACE2 receptor it uses to enter cells is common throughout the body, and inflammation from the immune response fighting that infection can damage surrounding tissue.

One of the most widely shared groups of symptoms is fatigue and what has come to be called “brain fog,” a difficulty focusing and an amorphous feeling of slowed mental functioning and capacity. Researchers have tied these COVID-related symptoms to tissue damage in specific sections of the brain and actual shrinkage in its size.

When Shai Efrati, medical director of the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research in Tel Aviv, first looked at functional magnetic resonance images (fMRIs) of patients with what is now called long COVID, he saw “micro infarcts along the brain.” It reminded him of similar lesions in other conditions he had treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). “Once we saw that, we said, this is the type of wound we can treat. It doesn't matter if the primary cause is mechanical injury like TBI [traumatic brain injury] or stroke … we know how to oxidize them.”Efrati came to HBOT almost by accident. The physician had seen how it had helped heal diabetic ulcers and improved the lives of other patients, but he was busy with his own research. Then the director of his Tel Aviv hospital threatened to shut down the small HBOT chamber unless Efrati took on administrative responsibility for it. He reluctantly agreed, a decision that shifted the entire focus of his research.

“The main difference between wounds in the leg and wounds in the brain is that one is something we can see, it's tangible, and the wound in the brain is hidden,” says Efrati. With fMRIs, he can measure how a limited supply of oxygen in blood is shuttled around to fuel activity in various parts of the brain. Years of research have mapped how specific areas of the brain control activity ranging from thinking to moving. An fMRI captures the brain area as it’s activated by supplies of oxygen; lack of activity after the same stimuli suggests damage has occurred in that tissue. Suddenly, what was hidden became visible to researchers using fMRI. It helped to make a diagnosis and measure response to treatment.

HBOT is not a single thing but rather a tool, a process or approach with variations depending on the condition being treated. It aims to increase the amount of oxygen that gets to damaged tissue and speed up healing. Regular air is about 21 percent oxygen. But inside the HBOT chamber the atmospheric pressure can be increased to up to three times normal pressure at sea level and the patient breathes pure oxygen through a mask; blood becomes saturated with much higher levels of oxygen. This can defuse through the damaged capillaries of a wound and promote healing.

The trial

Efrati’s clinical trials started in December 2020, barely a year after SARS-CoV-2 had first appeared in Israel. Patients who’d experienced cognitive issues after having COVID received 40 sessions in the chamber over a period of 60 days. In each session, they spent 90 minutes breathing through a mask at two atmospheres of pressure. While inside, they performed mental exercises to train the brain. The only difference between the two groups of patients was that one breathed pure oxygen while the other group breathed normal air. No one knew who was receiving which level of oxygen.

The results were striking. Before and after fMRIs showed significant repair of damaged tissue in the brain and functional cognition tests improved substantially among those who received pure oxygen. Importantly, 80 percent of patients said they felt back to “normal,” but Efrati says they didn't include patient evaluation in the paper because there was no baseline data to show how they functioned before COVID. After the study was completed, the placebo group was offered a new round of treatments using 100 percent oxygen, and the team saw similar results.

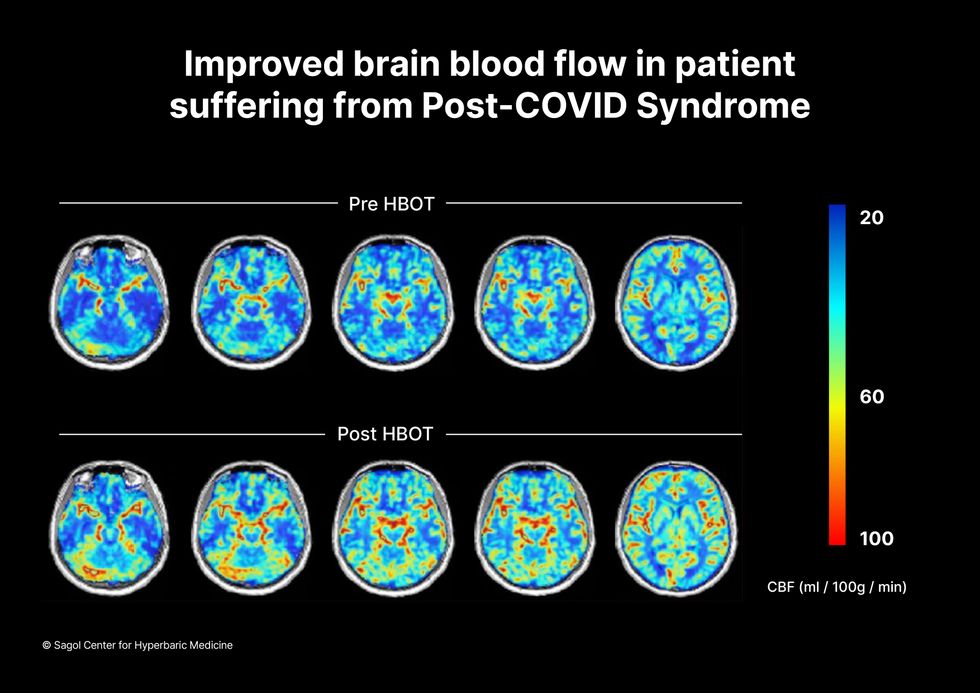

Scans show improved blood flow in a patient suffering from Long Covid.

Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine

Efrati's use of HBOT is part of an emerging geroscience approach to diseases associated with aging. These researchers see systems dysfunctions that are common to several diseases, such as inflammation, which has been shown to play a role in micro infarcts, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Preliminary research suggests that HBOT can retard some underlying mechanisms of aging, which might address several medical conditions. However, the drug approval process is set up to regulate individual disease, not conditions as broad as aging, and so they concentrate on treating the low hanging fruit: disorders where effective treatments currently are limited and success might be demonstrated.

The key to HBOT's effectiveness is something called the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox where a body does not react to an increase in available oxygen, only to a decrease, regardless of the starting point. That danger signal has a powerful effect on gene expression, resulting in changes in metabolism, and the proliferation of stem cells. That occurs with each cycle of 20 minutes of pure oxygen followed by 5 minutes of regular air circulating through the masks, while the chamber remains pressurized. The high levels of oxygen in the blood provide the fuel necessary for tissue regeneration.

The hyperbaric chamber that Efrati has built can hold a dozen patients and attending medical staff. Think of it as a pressurized airplane cabin, only with much more space than even in first class. In the U.S., people think of HBOT as “a sack of air or some tube that you can buy on Amazon” or find at a health spa. “That is total bullshit,” Efrati says. “It has to be a medical class center where a physician can lose their license if they are not operating it properly.”

Shai Efrati

Alexander Charney, a research psychiatrist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, calls Efrati’s study thoughtful and well designed. But it demands a lot from patients with its intense number of sessions. Those types of regimens have proven difficult to roll out to large numbers of patients. Still, the results are intriguing enough to merit additional trials.

John J. Miller, a physician and editor in chief of Psychiatric Times, has seen “many physicians that use hyperbaric oxygen for various brain disorders such as TBI.” He is intrigued by Efrati's work and believes the approach “has great potential to help patients with long COVID whose symptoms are related to brain tissue changes.”

Efrati believes so much in the power of the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox to heal a variety of tissue injuries that he is leading the medical advisory board at Aviv Clinic, an international network of clinics that are delivering HBOT treatments based on research conducted in Israel. His goal is to silence doubters by quickly opening about 50 such clinics worldwide, based on the model of standalone dialysis clinics in the United States. Sagol Center is treating 300 patients per day, and clinics have opened in Florida and Dubai. There are plans to open another in Manhattan.