Is Finding Out Your Baby’s Genetics A New Responsibility of Parenting?

A doctor pricks the heel of a newborn for a blood test.

Hours after a baby is born, its heel is pricked with a lancet. Drops of the infant's blood are collected on a porous card, which is then mailed to a state laboratory. The dried blood spots are screened for around thirty conditions, including phenylketonuria (PKU), the metabolic disorder that kick-started this kind of newborn screening over 60 years ago. In the U.S., parents are not asked for permission to screen their child. Newborn screening programs are public health programs, and the assumption is that no good parent would refuse a screening test that could identify a serious yet treatable condition in their baby.

Learning as much as you can about your child's health might seem like a natural obligation of parenting. But it's an assumption that I think needs to be much more closely examined.

Today, with the introduction of genome sequencing into clinical medicine, some are asking whether newborn screening goes far enough. As the cost of sequencing falls, should parents take a more expansive look at their children's health, learning not just whether they have a rare but treatable childhood condition, but also whether they are at risk for untreatable conditions or for diseases that, if they occur at all, will strike only in adulthood? Should genome sequencing be a part of every newborn's care?

It's an idea that appeals to Anne Wojcicki, the founder and CEO of the direct-to-consumer genetic testing company 23andMe, who in a 2016 interview with The Guardian newspaper predicted that having newborns tested would soon be considered standard practice—"as critical as testing your cholesterol"—and a new responsibility of parenting. Wojcicki isn't the only one excited to see everyone's genes examined at birth. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health and perhaps the most prominent advocate of genomics in the United States, has written that he is "almost certain … that whole-genome sequencing will become part of new-born screening in the next few years." Whether that would happen through state-mandated screening programs, or as part of routine pediatric care—or perhaps as a direct-to-consumer service that parents purchase at birth or receive as a baby-shower gift—is not clear.

Learning as much as you can about your child's health might seem like a natural obligation of parenting. But it's an assumption that I think needs to be much more closely examined, both because the results that genome sequencing can return are more complex and more uncertain than one might expect, and because parents are not actually responsible for their child's lifelong health and well-being.

What is a parent supposed to do about such a risk except worry?

Existing newborn screening tests look for the presence of rare conditions that, if identified early in life, before the child shows any symptoms, can be effectively treated. Sequencing could identify many of these same kinds of conditions (and it might be a good tool if it could be targeted to those conditions alone), but it would also identify gene variants that confer an increased risk rather than a certainty of disease. Occasionally that increased risk will be significant. About 12 percent of women in the general population will develop breast cancer during their lives, while those who have a harmful BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene variant have around a 70 percent chance of developing the disease. But for many—perhaps most—conditions, the increased risk associated with a particular gene variant will be very small. Researchers have identified over 600 genes that appear to be associated with schizophrenia, for example, but any one of those confers only a tiny increase in risk for the disorder. What is a parent supposed to do about such a risk except worry?

Sequencing results are uncertain in other important ways as well. While we now have the ability to map the genome—to create a read-out of the pairs of genetic letters that make up a person's DNA—we are still learning what most of it means for a person's health and well-being. Researchers even have a name for gene variants they think might be associated with a disease or disorder, but for which they don't have enough evidence to be sure. They are called "variants of unknown (or uncertain) significance (VUS), and they pop up in most people's sequencing results. In cancer genetics, where much research has been done, about 1 in 5 gene variants are reclassified over time. Most are downgraded, which means that a good number of VUS are eventually designated benign.

While one parent might reasonably decide to learn about their child's risk for a condition about which nothing can be done medically, a different, yet still thoroughly reasonable, parent might prefer to remain ignorant so that they can enjoy the time before their child is afflicted.

Then there's the puzzle of what to do about results that show increased risk or even certainty for a condition that we have no idea how to prevent. Some genomics advocates argue that even if a result is not "medically actionable," it might have "personal utility" because it allows parents to plan for their child's future needs, to enroll them in research, or to connect with other families whose children carry the same genetic marker.

Finding a certain gene variant in one child might inform parents' decisions about whether to have another—and if they do, about whether to use reproductive technologies or prenatal testing to select against that variant in a future child. I have no doubt that for some parents these personal utility arguments are persuasive, but notice how far we've now strayed from the serious yet treatable conditions that motivated governments to set up newborn screening programs, and to mandate such testing for all.

Which brings me to the other problem with the call for sequencing newborn babies: the idea that even if it's not what the law requires, it's what good parents should do. That idea is very compelling when we're talking about sequencing results that show a serious threat to the child's health, especially when interventions are available to prevent or treat that condition. But as I have shown, many sequencing results are not of this type.

While one parent might reasonably decide to learn about their child's risk for a condition about which nothing can be done medically, a different, yet still thoroughly reasonable, parent might prefer to remain ignorant so that they can enjoy the time before their child is afflicted. This parent might decide that the worry—and the hypervigilence it could inspire in them—is not in their child's best interest, or indeed in their own. This parent might also think that it should be up to the child, when he or she is older, to decide whether to learn about his or her risk for adult-onset conditions, especially given that many adults at high familial risk for conditions like Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease choose never to be tested. This parent will value the child's future autonomy and right not to know more than they value the chance to prepare for a health risk that won't strike the child until 40 or 50 years in the future.

Parents are not obligated to learn about their children's risk for a condition that cannot be prevented, has a small risk of occurring, or that would appear only in adulthood.

Contemporary understandings of parenting are famously demanding. We are asked to do everything within our power to advance our children's health and well-being—to act always in our children's best interests. Against that backdrop, the need to sequence every newborn baby's genome might seem obvious. But we should be skeptical. Many sequencing results are complex and uncertain. Parents are not obligated to learn about their children's risk for a condition that cannot be prevented, has a small risk of occurring, or that would appear only in adulthood. To suggest otherwise is to stretch parental responsibilities beyond the realm of childhood and beyond factors that parents can control.

No, the New COVID Vaccine Is Not "Morally Compromised"

As the proportion of vaccinated elderly people increases, family reunions become possible again -- but not if people reject the vaccines on religious grounds.

The approval of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine has been heralded as a major advance. A single-dose vaccine that is highly efficacious at removing the ability of the virus to cause severe disease, hospitalization, and death (even in the face of variants) is nothing less than pathbreaking. Anyone who is offered this vaccine should take it. However, one group advises its adherents to preferentially request the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines instead in the quest for morally "irreproachable" vaccines.

Is this group concerned about lower numerical efficacy in clinical trials? No, it seems that they have deemed the J&J vaccine "morally compromised". The group is the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and if something is "morally compromised" it is surely not the vaccine. (Notably Pope Francis has not taken such a stance).

At issue is a cell line used to manufacture the vaccine. Specifically, a cell line used to grow the adenovirus vector used in the vaccine. The purpose of the vector is to carry a genetic snippet of the coronavirus spike protein into the body, like a Trojan Horse ferrying in an enemy combatant, in order to safely trigger an immune response without any chance of causing COVID-19 itself.

It is my hope that the country's 50 million Catholics do not heed the U.S. Conference of Bishops' potentially deadly advice and instead obtain whichever vaccine is available to them as soon as possible.

The cell line of the vector, known as PER.C6, was derived from a fetus that was aborted in 1985. This cell line is prolific in biotechnology, as are other fetal-derived cell lines such as HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney), used in the manufacture of the Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Indeed, fetal cell lines are used in the manufacture of critical vaccines directed against pathogens such as hepatitis A, rubella, rabies, chickenpox, and shingles and were used to test the Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines (which, accordingly, the U.S. Conference of Bishops deem to only raise moral "concerns").

As such, fetal cell lines from abortions are a common and critical component of biotechnology that we all rely on to improve our health. Such cell lines have been used to help find treatments for cancer, Ebola, and many other diseases.

Dr. Andrea Gambotto, a vaccine scientist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, explained to Science magazine last year why fetal cells are so important to vaccine development: "Cultured [nonhuman] animal cells can produce the same proteins, but they would be decorated with different sugar molecules, which—in the case of vaccines—runs the risk of failing to evoke a robust and specific immune response." Thus, the fetal cells' human origins are key to their effectiveness.

So why the opposition to this life-saving technology, especially in the midst of the deadliest pandemic in over a century? How could such a technology be "morally compromised" when morality, as I understand it, is a code of values to guide human life on Earth with the purpose of enhancing well-being?

By any measure, the J&J vaccine accomplishes that, since human life, not embryonic or fetal life, is the standard of value. An embryo or fetus in the earlier stages of development, while harboring the potential to grow into a human being, is not the moral equivalent of a person. Thus, creating life-saving medical technology using cells that would have otherwise been destroyed is not in conflict with a proper moral code. To me, it is nihilistic to oppose these vaccines on the grounds cited by the U.S. Conference of Bishops.

Reason, the rational faculty, is the human means of knowledge. It is what one should wield when approaching a scientific or health issue. Appeals from clerics, devoid of any need to tether their principles to this world, should not have any bearing on one's medical decision-making.

In the Dark Ages, the Catholic Church opposed all forms of scientific inquiry, even castigating science and curiosity as the "lust of the eyes": One early Middle Ages church father reveled in his rejection of reality and evidence, proudly declaring, "I believe because it is absurd." This organization, which tyrannized scientists such as Galileo and murdered the Italian cosmologist Bruno, today has shown itself to still harbor anti-science sentiments in its ranks.

It is my hope that the country's 50 million Catholics do not heed the U.S. Conference of Bishops' potentially deadly advice and instead obtain whichever vaccine is available to them as soon as possible. When judged using the correct standard of value, vaccines using fetal cell lines in their development are an unequivocal good -- while those who attempt to undermine them deserve a different category altogether.

Dr. Adalja is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. He has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and the system of care for infectious disease emergencies, and as an external advisor to the New York City Health and Hospital Emergency Management Highly Infectious Disease training program, as well as on a FEMA working group on nuclear disaster recovery. Dr. Adalja is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security. He was a coeditor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine, the Emergency Medicine CorePendium, Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple, UpToDate's section on biological terrorism, and a NATO volume on bioterrorism. He has also published in such journals as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Annals of Emergency Medicine. He is a board-certified physician in internal medicine, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. Follow him on Twitter: @AmeshAA

Donna Shirley pictured at her home in Tulsa, with a model of the Sojourner rover she was in charge of that explored Mars.

When NASA's Perseverance rover landed successfully on Mars on February 18, 2021, calling it "one giant leap for mankind" – as Neil Armstrong said when he set foot on the moon in 1969 – would have been inaccurate. This year actually marked the fifth time the U.S. space agency has put a remote-controlled robotic exploration vehicle on the Red Planet. And it was a female engineer named Donna Shirley who broke new ground for women in science as the manager of both the Mars Exploration Program and the 30-person team that built Sojourner, the first rover to land on Mars on July 4, 1997.

For Shirley, the Mars Pathfinder mission was the climax of her 32-year career at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The Oklahoma-born scientist, who earned her Master's degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Southern California, saw her profile skyrocket with media appearances from CNN to the New York Times, and her autobiography Managing Martians came out in 1998. Now 79 and living in a Tulsa retirement community, she still embraces her status as a female pioneer.

"Periodically, I'll hear somebody say they got into the space program because of me, and that makes me feel really good," Shirley told Leaps.org. "I look at the mission control area, and there are a lot of women in there. I'm quite pleased I was able to break the glass ceiling."

Her $25-million, 25-pound microrover – powered by solar energy and designed to get rock samples and test soil chemistry for evidence of life – was named after Sojourner Truth, a 19th-century Black abolitionist and women's rights activist. Unlike Mars Pathfinder, Shirley didn't have to travel more than 131 million miles to reach her goal, but her path to scientific fame as a woman sometimes resembled an asteroid field.

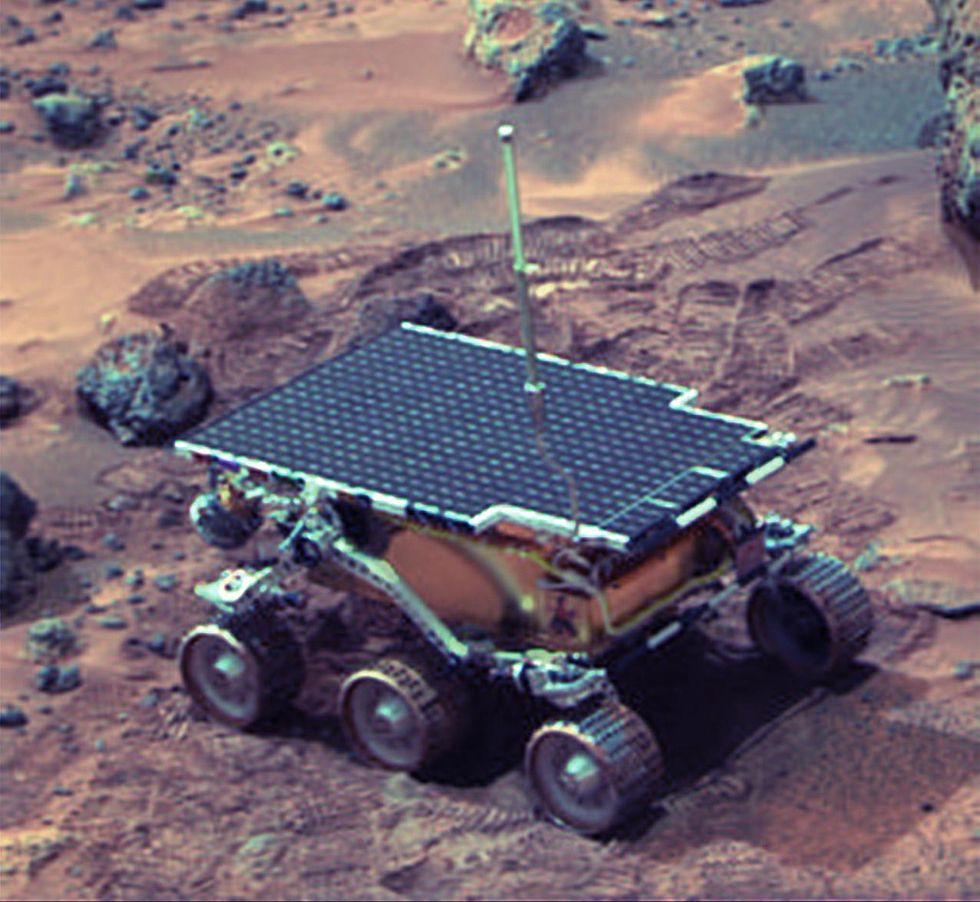

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.

NASA/JPL

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.

NASA/JPL

As a high-IQ tomboy growing up in Wynnewood, Oklahoma (pop. 2,300), Shirley yearned to escape. She decided to become an engineer at age 10 and took flying lessons at 15. Her extraterrestrial aspirations were fueled by Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles and Arthur C. Clarke's The Sands of Mars. Yet when she entered the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1958, her freshman academic advisor initially told her: "Girls can't be engineers." She ignored him.

Years later, Shirley would combat such archaic thinking, succeeding at JPL with her creative, collaborative management style. "If you look at the literature, you'll find that teams that are either led by or heavily involved with women do better than strictly male teams," she noted.

However, her career trajectory stalled at OU. Burned out by her course load and distracted by a broken engagement to marry a fellow student, she switched her major to professional writing. After graduation, she applied her aeronautical background as a McDonnell Aircraft technical writer, but her boss, she says, harassed her and she faced gender-based hostility from male co-workers.

Returning to OU, Shirley finished off her engineering degree and became a JPL aerodynamist in 1966 after answering an ad in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. At first, she was the only female engineer among the research center's 2,000-odd engineers. She wore many hats, from designing planetary atmospheric entry vehicles to picking the launch date of November 4, 1973 for Mariner 10's mission to Venus and Mercury.

By the mid-1980's, she was managing teams that focused on robotics and Mars, delivering creative solutions when NASA budget cuts loomed. In 1989, the same year the Sojourner microrover concept was born, President George H.W. Bush announced his Space Exploration Initiative, including plans for a human mission to Mars by 2019.

That target, of course, wasn't attained, despite huge advances in technology and our understanding of the Martian environment. Today, Shirley believes humans could land on Mars by 2030. She became the founding director of the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle in 2004 after leaving NASA, and to this day, she enjoys checking out pop culture portrayals of Mars landings – even if they're not always accurate.

After the novel The Martian was published in 2011, which later was adapted into the hit film starring Matt Damon, Shirley phoned author Andy Weir: "You've got a major mistake in here. It says there's a storm that tries to blow the rocket over. But actually, the Mars atmosphere is so thin, it would never blow a rocket over!"

Fearlessly speaking her mind and seeking the stars helped Donna Shirley make history. However, a 2019 Washington Post story noted: "Women make up only about a third of NASA's workforce. They comprise just 28 percent of senior executive leadership positions and are only 16 percent of senior scientific employees." Whether it's traveling to Mars or trending toward gender equality, we've still got a long way to go.