Is It Possible to Predict Your Face, Voice, and Skin Color from Your DNA?

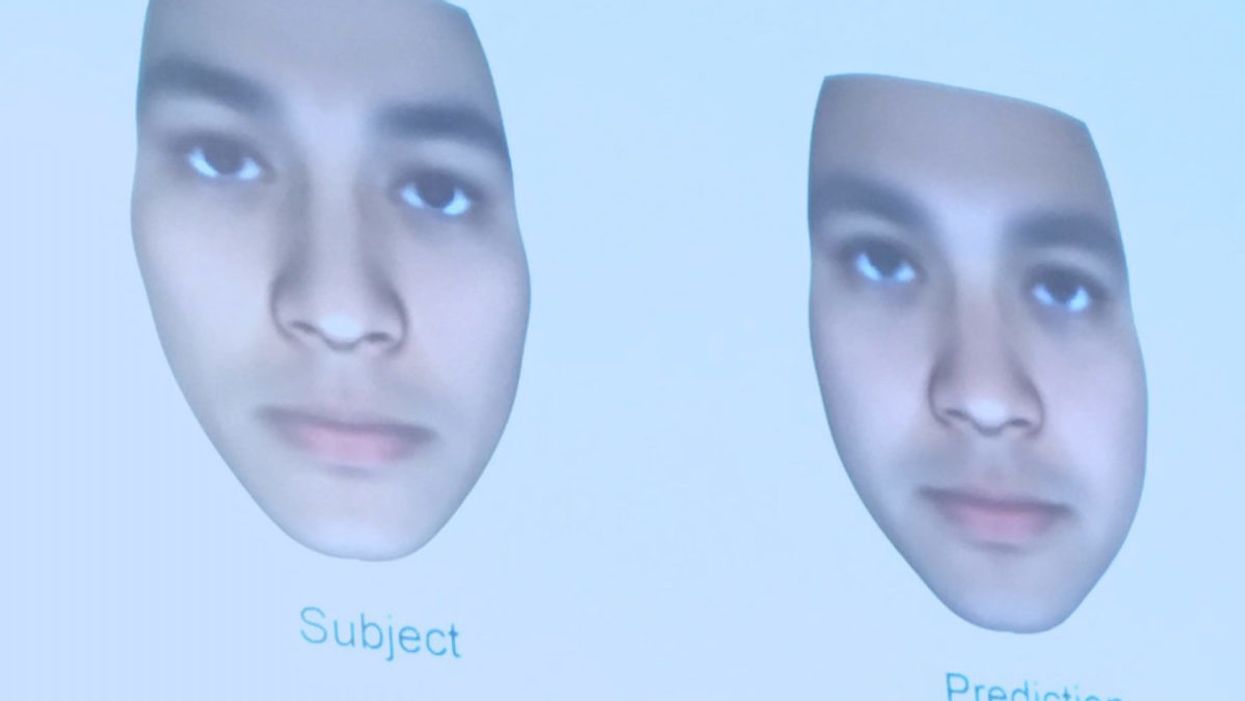

A slide from J. Craig Venter's recent study on facial prediction presented at the Summit Conference in Los Angeles on Nov. 3, 2017.

Renowned genetics pioneer Dr. J Craig Venter is no stranger to controversy.

Back in 2000, he famously raced the public Human Genome Project to decode all three billion letters of the human genome for the first time. A decade later, he ignited a new debate when his team created a bacterial cell with a synthesized genome.

Most recently, he's jumped back into the fray with a study in the September issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences about the predictive potential of genomic data to identify individual traits such as voice, facial structure and skin color.

The new study raises significant questions about the privacy of genetic data.

His study applied whole-genome sequencing and statistical modeling to predict traits in 1,061 people of diverse ancestry. His approach aimed to reconstruct a person's physical characteristics based on DNA, and 74 percent of the time, his algorithm could correctly identify the individual in a random lineup of 10 people from his company's database.

While critics have been quick to cast doubt on the plausibility of his claims, the ability to discern people's observable traits, or phenotypes, from their genomes may grow more precise as technology improves, raising significant questions about the privacy and usage of genetic information in the long term.

J. Craig Venter showing slides from his recent study on facial prediction at the Summit Conference in Los Angeles on Nov. 3, 2017.

(Courtesy of Kira Peikoff)

Critics: Study Was Incomplete, Problematic

Before even redressing these potential legal and ethical considerations, some scientists simply said the study's main result was invalid. They pointed out that the methodology worked much better in distinguishing between people of different ethnicities than those of the same ethnicity. One of the most outspoken critics, Yaniv Erlich, a geneticist at Columbia University, said, "The method doesn't work. The results were like, 'If you have a lineup of ten people, you can predict eight."

Erlich, who reviewed Venter's paper for Science, where it was rejected, said that he came up with the same results—correctly predicting eight of ten people—by just looking at demographic factors such as age, gender and ethnicity. He added that Venter's recent rebuttal to his criticism was that 'Once we have thousands of phenotypes, it might work better.' But that, Erlich argued, would be "a major breach of privacy. Nobody has thousands of phenotypes for people."

Other critics suggested that the study's results discourage the sharing of genetic data, which is becoming increasingly important for medical research. They go one step further and imply that people's possible hesitation to share their genetic information in public databases may actually play into Venter's hands.

Venter's own company, Human Longevity Inc., aims to build the world's most comprehensive private database on human genotypes and phenotypes. The vastness of this information stands to improve the accuracy of whole genome and microbiome sequencing for individuals—analyses that come at a hefty price tag. Today, Human Longevity Inc. will sequence your genome and perform a battery of other health-related tests at an entry cost of $4900, going up to $25,000. Venter initially agreed to comment for this article, but then could not be reached.

"The bigger issue is how do we understand and use genetic information and avoid harming people."

Opens Up Pandora's Box of Ethical Issues

Whether Venter's study is valid may not be as important as the Pandora's box of potential ethical and legal issues that it raises for future consideration. "I think this story is one along a continuum of stories we've had on the issue of identifiability based on genomic information in the past decade," said Amy McGuire, a biomedical ethics professor at Baylor College of Medicine. "It does raise really interesting and important questions about privacy, and socially, how we respond to these types of scientific advancements. A lot of our focus from a policy and ethics perspective is to protect privacy."

McGuire, who is also the Director of the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor, added that while protecting privacy is very important, "the bigger issue is how do we understand and use genetic information and avoid harming people." While we've taken "baby steps," she said, towards enacting laws in the U.S. that fight genetic determinism—such as the Genetic Information and Nondiscrimination Act, which prohibits discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment—some areas remain unprotected, such as for life insurance and disability.

J. Craig Venter showing slides from his recent study on facial prediction at the Summit Conference in Los Angeles on Nov. 3, 2017.

(Courtesy of Kira Peikoff)

Physical reconstructions like those in Venter's study could also be inappropriately used by law enforcement, said Leslie Francis, a law and philosophy professor at the University of Utah, who has written about the ethical and legal issues related to sharing genomic data.

"If [Venter's] findings, or findings like them, hold up, the implications would be significant," Francis said. Law enforcement is increasingly using DNA identification from genetic material left at crime scenes to weed out innocent and guilty suspects, she explained. This adds another potentially complicating layer.

"There is a shift here, from using DNA sequencing techniques to match other DNA samples—as when semen obtained from a rape victim is then matched (or not) with a cheek swab from a suspect—to using DNA sequencing results to predict observable characteristics," Francis said. She added that while the former necessitates having an actual DNA sample for a match, the latter can use DNA to pre-emptively (and perhaps inaccurately) narrow down suspects.

"My worry is that if this [the study's methodology] turns out to be sort-of accurate, people will think it is better than what it is," said Francis. "If law enforcement comes to rely on it, there will be a host of false positives and false negatives. And we'll face new questions, [such as] 'Which is worse? Picking an innocent as guilty, or failing to identify someone who is guilty?'"

Risking Privacy Involves a Tradeoff

When people voluntarily risk their own privacy, that involves a tradeoff, McGuire said. A 2014 study that she conducted among people who were very sick, or whose children were very sick, found that more than half were willing to share their health information, despite concerns about privacy, because they saw a big benefit in advancing research on their conditions.

"We've focused a lot of our policy attention on restricting access, but we don't have a system of accountability when there's a breach."

"To make leaps and bounds in medicine and genomics, we need to create a database of millions of people signing on to share their genetic and health information in order to improve research and clinical care," McGuire said. "They are going to risk their privacy, and we have a social obligation to protect them."

That also means "punishing bad actors," she continued. "We've focused a lot of our policy attention on restricting access, but we don't have a system of accountability when there's a breach."

Even though most people using genetic information have good intentions, the consequences if not are troubling. "All you need is one bad actor who decimates the trust in the system, and it has catastrophic consequences," she warned. That hasn't happened on a massive scale yet, and even if it did, some experts argue that obtaining the data is not the real risk; what is more concerning is hacking individuals' genetic information to be used against them, such as to prove someone is unfit for a particular job because of a genetic condition like Alzheimer's, or that a parent is unfit for custody because of a genetic disposition to mental illness.

Venter, in fact, told an audience at the recent Summit conference in Los Angeles that his new study's approach could not only predict someone's physical appearance from their DNA, but also some of their psychological traits, such as the propensity for an addictive personality. In the future, he said, it will be possible to predict even more about mental health from the genome.

What is most at risk on a massive scale, however, is not so much genetic information as demographic identifiers included in medical records, such as birth dates and social security numbers, said Francis, the law and philosophy professor. "The much more interesting and lucrative security breaches typically involve not people interested in genetic information per se, but people interested in the information in health records that you can't change."

Hospitals have been hacked for this kind of information, including an incident at the Veterans Administration in 2006, in which the laptop and external hard drive of an agency employee that contained unencrypted information on 26.5 million patients were stolen from the employee's house.

So, what can people do to protect themselves? "Don't share anything you wouldn't want the world to see," Francis said. "And don't click 'I agree' without actually reading privacy policies or terms and conditions. They may surprise you."

This man spent over 70 years in an iron lung. What he was able to accomplish is amazing.

Paul Alexander spent more than 70 years confined to an iron lung after a polio infection left him paralyzed at age 6. Here, Alexander uses a mirror attached to the top of his iron lung to view his surroundings.

It’s a sight we don’t normally see these days: A man lying prone in a big, metal tube with his head sticking out of one end. But it wasn’t so long ago that this sight was unfortunately much more common.

In the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of people each year were infected by polio—a highly contagious virus that attacks nerves in the spinal cord and brainstem. Many people survived polio, but a small percentage of people who did were left permanently paralyzed from the virus, requiring support to help them breathe. This support, known as an “iron lung,” manually pulled oxygen in and out of a person’s lungs by changing the pressure inside the machine.

Paul Alexander was one of several thousand who were infected and paralyzed by polio in 1952. That year, a polio epidemic swept the United States, forcing businesses to close and polio wards in hospitals all over the country to fill up with sick children. When Paul caught polio in the summer of 1952, doctors urged his parents to let him rest and recover at home, since the hospital in his home suburb of Dallas, Texas was already overrun with polio patients.

Paul rested in bed for a few days with aching limbs and a fever. But his condition quickly got worse. Within a week, Paul could no longer speak or swallow, and his parents rushed him to the local hospital where the doctors performed an emergency procedure to help him breathe. Paul woke from the surgery three days later, and found himself unable to move and lying inside an iron lung in the polio ward, surrounded by rows of other paralyzed children.

But against all odds, Paul lived. And with help from a physical therapist, Paul was able to thrive—sometimes for small periods outside the iron lung.

The way Paul did this was to practice glossopharyngeal breathing (or as Paul called it, “frog breathing”), where he would trap air in his mouth and force it down his throat and into his lungs by flattening his tongue. This breathing technique, taught to him by his physical therapist, would allow Paul to leave the iron lung for increasing periods of time.

With help from his iron lung (and for small periods of time without it), Paul managed to live a full, happy, and sometimes record-breaking life. At 21, Paul became the first person in Dallas, Texas to graduate high school without attending class in person, owing his success to memorization rather than taking notes. After high school, Paul received a scholarship to Southern Methodist University and pursued his dream of becoming a trial lawyer and successfully represented clients in court.

Throughout his long life, Paul was also able to fly on a plane, visit the beach, adopt a dog, fall in love, and write a memoir using a plastic stick to tap out a draft on a keyboard. In recent years, Paul joined TikTok and became a viral sensation with more than 330,000 followers. In one of his first videos, Paul advocated for vaccination and warned against another polio epidemic.

Paul was reportedly hospitalized with COVID-19 at the end of February and died on March 11th, 2024. He currently holds the Guiness World Record for longest survival inside an iron lung—71 years.

Polio thankfully no longer circulates in the United States, or in most of the world, thanks to vaccines. But Paul continues to serve as a reminder of the importance of vaccination—and the power of the human spirit.

““I’ve got some big dreams. I’m not going to accept from anybody their limitations,” he said in a 2022 interview with CNN. “My life is incredible.”

When doctors couldn’t stop her daughter’s seizures, this mom earned a PhD and found a treatment herself.

Savannah Salazar (left) and her mother, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar, who earned a PhD in neurobiology in the quest for a treatment of her daughter's seizure disorder.

Twenty-eight years ago, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar woke to the sound of her daughter, two-year-old Savannah, in the midst of a medical emergency.

“I entered [Savannah’s room] to see her tiny little body jerking about violently in her bed,” Tracy said in an interview. “I thought she was choking.” When she and her husband frantically called 911, the paramedic told them it was likely that Savannah had had a seizure—a term neither Tracy nor her husband had ever heard before.

Over the next several years, Savannah’s seizures continued and worsened. By age five Savannah was having seizures dozens of times each day, and her parents noticed significant developmental delays. Savannah was unable to use the restroom and functioned more like a toddler than a five-year-old.

Doctors were mystified: Tracy and her husband had no family history of seizures, and there was no event—such as an injury or infection—that could have caused them. Doctors were also confused as to why Savannah’s seizures were happening so frequently despite trying different seizure medications.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Savannah with Lennox-Gaustaut Syndrome, or LGS, an epilepsy disorder with no cure and a poor prognosis. People with LGS are often resistant to several kinds of anti-seizure medications, and often suffer from developmental delays and behavioral problems. People with LGS also have a higher chance of injury as well as a higher chance of sudden unexpected death (SUDEP) due to the frequent seizures. In about 70 percent of cases, LGS has an identifiable cause such as a brain injury or genetic syndrome. In about 30 percent of cases, however, the cause is unknown.

Watching her daughter struggle through repeated seizures was devastating to Tracy and the rest of the family.

“This disease, it comes into your life. It’s uninvited. It’s unannounced and it takes over every aspect of your daily life,” said Tracy in an interview with Today.com. “Plus it’s attacking the thing that is most precious to you—your kid.”

Desperate to find some answers, Tracy began combing the medical literature for information about epilepsy and LGS. She enrolled in college courses to better understand the papers she was reading.

“Ironically, I thought I needed to go to college to take English classes to understand these papers—but soon learned it wasn’t English classes I needed, It was science,” Tracy said. When she took her first college science course, Tracy says, she “fell in love with the subject.”

Tracy was now a caregiver to Savannah, who continued to have hundreds of seizures a month, as well as a full-time student, studying late into the night and while her kids were at school, using classwork as “an outlet for the pain.”

“I couldn’t help my daughter,” Tracy said. “Studying was something I could do.”

Twelve years later, Tracy had earned a PhD in neurobiology.

After her post-doctoral training, Tracy started working at a lab that explored the genetics of epilepsy. Savannah’s doctors hadn’t found a genetic cause for her seizures, so Tracy decided to sequence her genome again to check for other abnormalities—and what she found was life-changing.

Tracy discovered that Savannah had a calcium channel mutation, meaning that too much calcium was passing through Savannah’s neural pathways, leading to seizures. The information made sense to Tracy: Anti-seizure medications often leech calcium from a person’s bones. When doctors had prescribed Savannah calcium supplements in the past to counteract these effects, her seizures had gotten worse every time she took the medication. Tracy took her discovery to Savannah’s doctor, who agreed to prescribe her a calcium blocker.

The change in Savannah was almost immediate.

Within two weeks, Savannah’s seizures had decreased by 95 percent. Once on a daily seven-drug regimen, she was soon weaned to just four, and then three. Amazingly, Tracy started to notice changes in Savannah’s personality and development, too.

“She just exploded in her personality and her talking and her walking and her potty training and oh my gosh she is just so sassy,” Tracy said in an interview.

Since starting the calcium blocker eleven years ago, Savannah has continued to make enormous strides. Though still unable to read or write, Savannah enjoys puzzles and social media. She’s “obsessed” with boys, says Tracy. And while Tracy suspects she’ll never be able to live independently, she and her daughter can now share more “normal” moments—something she never anticipated at the start of Savannah’s journey with LGS. While preparing for an event, Savannah helped Tracy get ready.

“We picked out a dress and it was the first time in our lives that we did something normal as a mother and a daughter,” she said. “It was pretty cool.”