Is There a Blind Spot in the Oversight of Human Subject Research?

A scientist examining samples.

Human experimentation has come a long way since congressional hearings in the 1970s exposed patterns of abuse. Where yesterday's patients were protected only by the good conscience of physician-researchers, today's patients are spirited past hazards through an elaborate system of oversight and informed consent. Yet in many ways, the project of grounding human research on ethical foundations remains incomplete.

As human research has become a mainstay of career and commercial advancement among academics, research centers, and industry, new threats to research integrity have emerged.

To be sure, much of the medical research we do meets exceedingly high standards. Progress in cancer immunotherapy, or infectious disease, reflects the best of what can be accomplished when medical scientists and patients collaborate productively. And abuses of the earlier part of the 20th century--like those perpetrated by the U.S. Public Health Service in Guatemala--are for the history books.

Yet as human research has become a mainstay of career and commercial advancement among academics, research centers, and industry, new threats to research integrity have emerged. Many flourish in the blind spot of current oversight systems.

Take, for example, the tendency to publish only "positive" findings ("publication bias"). When patients participate in studies, they are told that their contributions will promote medical discovery. That can't happen if results of experiments never get beyond the hard drives of researchers. While researchers are often eager to publish trials showing a drug works, according to a study my own team conducted, fewer than 4 in 10 trials of drugs that never receive FDA approval get published. This tendency- which occurs in academia as well as industry- deprives other scientists of opportunities to build on these failures and make good on the sacrifice of patients. It also means the trials may be inadvertently repeated by other researchers, subjecting more patients to risks.

On the other hand, many clinical trials test treatments that have already been proven effective beyond a shadow of doubt. Consider the drug aprotinin, used for the management of bleeding during surgery. An analysis in 2005 showed that, not long after the drug was proven effective, researchers launched dozens of additional placebo-controlled trials. These redundant trials are far in excess of what regulators required for drug approval, and deprived patients in placebo arms of a proven effective therapy. Whether because of an oversight or deliberately (does it matter?), researchers conducting these trials often failed in publications to describe previous evidence of efficacy. What's the point of running a trial if no one reads the results?

It is surprisingly easy for companies to hijack research to market their treatments.

At the other extreme are trials that are little more than shots in the dark. In one case, patients with spinal cord injury were enrolled in a safety trial testing a cell-based regenerative medicine treatment. After the trial stopped (results were negative), laboratory scientists revealed that the cells had been shown ineffective in animal experiments. Though this information had been available to the company and FDA, researchers pursued the trial anyway.

It is surprisingly easy for companies to hijack research to market their treatments. One way this happens is through "seeding trials"- studies that are designed not to address a research question, but instead to habituate doctors to using a new drug and to generate publications that serve as advertisements. Such trials flood the medical literature with findings that are unreliable because studies are small and not well designed. They also use the prestige of science to pursue goals that are purely commercial. Yet because they harm science- not patients (many such studies are minimally risky because all patients receive proven effective medications)- ethics committees rarely block them.

Closely related is the phenomenon of small uninformative trials. After drugs get approved by the FDA, companies often launch dozens of small trials in new diseases other than the one the drug was approved to treat. Because these studies are small, they often overestimate efficacy. Indeed, the way trials are often set up, if a company tests an ineffective drug in 40 different studies, one will typically produce a false positive by chance alone. Because companies are free to run as many trials as they like and to circulate "positive" results, they have incentives to run lots of small trials that don't provide a definitive test of their drug's efficacy.

Universities, funding bodies, and companies should be scored by a neutral third-party based on the impact of their trials -- like Moody's for credit ratings.

Don't think public agencies are much better. Funders like the National Institutes of Health secure their appropriations by gratifying Congress. This means that NIH gets more by spreading its funding among small studies in different Congressional districts than by concentrating budgets among a few research institutions pursuing large trials. The result is that some NIH-funded clinical trials are not especially equipped to inform medical practice.

It's tempting to think that FDA, medical journals, ethics committees, and funding agencies can fix these problems. However, these practices continue in part because FDA, ethics committees, and researchers often do not see what is at stake for patients by acquiescing to low scientific standards. This behavior dishonors the patients who volunteer for research, and also threatens the welfare of downstream patients, whose care will be determined by the output of research.

To fix this, deficiencies in study design and reporting need to be rendered visible. Universities, funding bodies, and companies should be scored by a neutral third-party based on the impact of their trials, or the extent to which their trials are published in full -- like Moody's for credit ratings, or the Kelley Blue Book for cars. This system of accountability would allow everyone to see which institutions make the most of the contributions of research subjects. It could also harness the competitive instincts of institutions to improve research quality.

Another step would be for researchers to level with patients when they enroll in studies. Patients who agree to research are usually offered bromides about how their participation may help future patients. However, not all studies are created equal with respect to merit. Patients have a right to know when they are entering studies that are unlikely to have a meaningful impact on medicine.

Ethics committees and drug regulators have done a good job protecting research volunteers from unchecked scientific ambition. However, today's research is plagued by studies that have poor scientific credentials. Such studies free-ride on the well-earned reputation of serious medical science. They also potentially distort the evidence available to physicians and healthcare systems. Regulators, academic medical centers, and others should establish policies that better protect human research volunteers by protecting the quality of the research itself.

Tech-related injuries are becoming more common as many people depend on - and often develop addictions for - smart phones and computers.

In the 1990s, a mysterious virus spread throughout the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Lab—or that’s what the scientists who worked there thought. More of them rubbed their aching forearms and massaged their cricked necks as new computers were introduced to the AI Lab on a floor-by-floor basis. They realized their musculoskeletal issues coincided with the arrival of these new computers—some of which were mounted high up on lab benches in awkward positions—and the hours spent typing on them.

Today, these injuries have become more common in a society awash with smart devices, sleek computers, and other gadgets. And we don’t just get hurt from typing on desktop computers; we’re massaging our sore wrists from hours of texting and Facetiming on phones, especially as they get bigger in size.

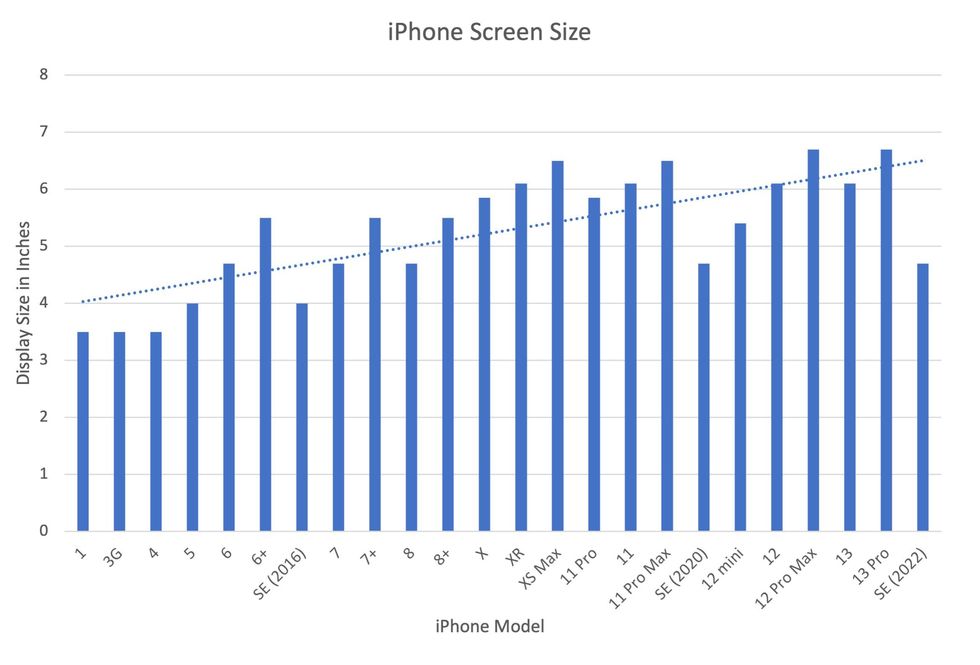

In 2007, the first iPhone measured 3.5-inches diagonally, a measurement known as the display size. That’s been nearly doubled by the newest iPhone 13 Pro, which has a 6.7-inch display. Other phones, too, like the Google Pixel 6 and the Samsung Galaxy S22, have bigger screens than their predecessors. Physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons have had to come up with names for a variety of new conditions: selfie elbow, tech neck, texting thumb. Orthopedic surgeon Sonya Sloan says she sees selfie elbow in younger kids and in women more often than men. She hears complaints related to technology once or twice a day.

The addictive quality of smartphones and social media means that people spend more time on their devices, which exacerbates injuries. According to Statista, 68 percent of those surveyed spent over three hours a day on their phone, and almost half spent five to six hours a day. Another report showed that people dedicate a third of their day to checking their phones, while the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has found that bigger screens, ideal for entertainment purposes, immerse their users more than smaller screens. Oversized screens also provide easier navigation and more space for those with bigger hands or trouble seeing.

But others with conditions like arthritis can benefit from smaller phones. In March of 2016, Apple released the iPhone SE with a display size of 4.7 inches—an inch smaller than the iPhone 7, released that September. Apple has since come out with two more versions of the diminutive iPhone SE, one in 2020 and another in 2022.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance science journalist, has the Google Pixel 6. She was drawn to the phone because Google marketed the Pixel 6’s camera as better at capturing different skin tones. But this phone boasts one of the largest display sizes on the market: 6.4 inches.

Senapathy was diagnosed with carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes in 2017 and fibromyalgia in 2019. She has had to create a curated ergonomic workplace setup, otherwise her wrists and hands get weak and tingly, and she’s had to adjust how she holds her phone to prevent pain flares.

Recently, Senapathy underwent an electromyography, or an EMG, in which doctors insert electrodes into muscles to measure their electrical activity. The electrical response of the muscles tells doctors whether the nerve cells and muscles are successfully communicating. Depending on her results, steroid shots and even surgery might be required. Senapathy wants to stick with her Pixel 6, but the pain she’s experiencing may push her to buy a smaller phone. Unfortunately, options for these modestly sized phones are more limited.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers like Senapathy to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable for creating addictive devices that lead to musculoskeletal injury?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance journalist, bought the Google Pixel 6 because of its high-quality camera, but she’s had to adjust how she holds the oversized phone to prevent pain flares.

Kavin Senapathy

A one-size-fits-all mentality for smartphones will continue to lead to injuries because every user has different wants and needs. S. Shyam Sundar, the founder of Penn State’s lab on media effects and a communications professor, says the needs for mobility and portability conflict with the desire for greater visibility. “The best thing a company can do is offer different sizes,” he says.

Joanna Bryson, an AI ethics expert and professor at The Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of the lack of choice we see comes from the fact that the markets have consolidated so much,” she says. “We want to make sure there’s sufficient diversity [of products].”

Consumers can still maintain some control despite the ubiquity of tech. Sloan, the orthopedic surgeon, has to pester her son to change his body positioning when using his tablet. Our heads get heavier as they bend forward: at rest, they weigh 12 pounds, but bent 60 degrees, they weigh 60. “I have to tell him, ‘Raise your head, son!’” she says. It’s important, Sloan explains, to consider that growth and development will affect ligaments and bones in the neck, potentially making kids even more vulnerable to injuries from misusing gadgets. She recommends that parents limit their kids’ tech time to alleviate strain. She also suggested that tech companies implement a timer to remind us to change our body positioning.

In 2017, Nan-Wei Gong, a former contractor for Google, founded Figur8, which uses wearable trackers to measure muscle function and joint movement. It’s like physical therapy with biofeedback. “Each unique injury has a different biomarker,” says Gong. “With Figur8, you are comparing yourself to yourself.” This allows an individual to self-monitor for wear and tear and strengthen an injury in a way that’s efficient and designed for their body. Gong noticed that the work-from-home model during the COVID-19 pandemic created a new set of ergonomic problems that resulted in injuries. Figur8 provides real-time data for these injuries because “behavioral change requires feedback.”

Gong worked on a project called Jacquard while at Google. Textile experts weave conductive thread into their fabric, and the result is a patch of the fabric—like the cuff of a Levi’s jacket—that responds to commands on your smartphone. One swipe can call your partner or check the weather. It was designed with cyclists in mind who can’t easily check their phones, and it’s part of a growing movement in the tech industry to deliver creative, hands-free design. Gong thinks that engineers at large corporations like Google have accessibility in mind; it’s part of what drives their decisions for new products.

Display sizes of iPhones have become larger over time.

Sourced from Screenrant https://screenrant.com/iphone-apple-release-chronological-order-smartphone/ and Apple Tech Specs: https://www.apple.com/iphone-se/specs/

Back in Germany, Joanna Bryson reminds us that products like smartphones should adhere to best practices. These rules may be especially important for phones and other products with AI that are addictive. Disclosure, accountability, and regulation are important for AI, she says. “The correct balance will keep changing. But we have responsibilities and obligations to each other.” She was on an AI Ethics Council at Google, but the committee was disbanded after only one week due to issues with one of their members.

Bryson was upset about the Council’s dissolution but has faith that other regulatory bodies will prevail. OECD.AI, and international nonprofit, has drafted policies to regulate AI, which countries can sign and implement. “As of July 2021, 46 governments have adhered to the AI principles,” their website reads.

Sundar, the media effects professor, also directs Penn State’s Center for Socially Responsible AI. He says that inclusivity is a crucial aspect of social responsibility and how devices using AI are designed. “We have to go beyond first designing technologies and then making them accessible,” he says. “Instead, we should be considering the issues potentially faced by all different kinds of users before even designing them.”

Entomologist Jessica Ware is using new technologies to identify insect species in a changing climate. She shares her suggestions for how we can live harmoniously with creeper crawlers everywhere.

Jessica Ware is obsessed with bugs.

My guest today is a leading researcher on insects, the president of the Entomological Society of America and a curator at the American Museum of Natural History. Learn more about her here.

You may not think that insects and human health go hand-in-hand, but as Jessica makes clear, they’re closely related. A lot of people care about their health, and the health of other creatures on the planet, and the health of the planet itself, but researchers like Jessica are studying another thing we should be focusing on even more: how these seemingly separate areas are deeply entwined. (This is the theme of an upcoming event hosted by Leaps.org and the Aspen Institute.)

Listen to the Episode

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Entomologist Jessica Ware

D. Finnin / AMNH

Maybe it feels like a core human instinct to demonize bugs as gross. We seem to try to eradicate them in every way possible, whether that’s with poison, or getting out our blood thirst by stomping them whenever they creep and crawl into sight.

But where did our fear of bugs really come from? Jessica makes a compelling case that a lot of it is cultural, rather than in-born, and we should be following the lead of other cultures that have learned to live with and appreciate bugs.

The truth is that a healthy planet depends on insects. You may feel stung by that news if you hate bugs. Reality bites.

Jessica and I talk about whether learning to live with insects should include eating them and gene editing them so they don’t transmit viruses. She also tells me about her important research into using genomic tools to track bugs in the wild to figure out why and how we’ve lost 50 percent of the insect population since 1970 according to some estimates – bad news because the ecosystems that make up the planet heavily depend on insects. Jessica is leading the way to better understand what’s causing these declines in order to start reversing these trends to save the insects and to save ourselves.