Is There a Blind Spot in the Oversight of Human Subject Research?

A scientist examining samples.

Human experimentation has come a long way since congressional hearings in the 1970s exposed patterns of abuse. Where yesterday's patients were protected only by the good conscience of physician-researchers, today's patients are spirited past hazards through an elaborate system of oversight and informed consent. Yet in many ways, the project of grounding human research on ethical foundations remains incomplete.

As human research has become a mainstay of career and commercial advancement among academics, research centers, and industry, new threats to research integrity have emerged.

To be sure, much of the medical research we do meets exceedingly high standards. Progress in cancer immunotherapy, or infectious disease, reflects the best of what can be accomplished when medical scientists and patients collaborate productively. And abuses of the earlier part of the 20th century--like those perpetrated by the U.S. Public Health Service in Guatemala--are for the history books.

Yet as human research has become a mainstay of career and commercial advancement among academics, research centers, and industry, new threats to research integrity have emerged. Many flourish in the blind spot of current oversight systems.

Take, for example, the tendency to publish only "positive" findings ("publication bias"). When patients participate in studies, they are told that their contributions will promote medical discovery. That can't happen if results of experiments never get beyond the hard drives of researchers. While researchers are often eager to publish trials showing a drug works, according to a study my own team conducted, fewer than 4 in 10 trials of drugs that never receive FDA approval get published. This tendency- which occurs in academia as well as industry- deprives other scientists of opportunities to build on these failures and make good on the sacrifice of patients. It also means the trials may be inadvertently repeated by other researchers, subjecting more patients to risks.

On the other hand, many clinical trials test treatments that have already been proven effective beyond a shadow of doubt. Consider the drug aprotinin, used for the management of bleeding during surgery. An analysis in 2005 showed that, not long after the drug was proven effective, researchers launched dozens of additional placebo-controlled trials. These redundant trials are far in excess of what regulators required for drug approval, and deprived patients in placebo arms of a proven effective therapy. Whether because of an oversight or deliberately (does it matter?), researchers conducting these trials often failed in publications to describe previous evidence of efficacy. What's the point of running a trial if no one reads the results?

It is surprisingly easy for companies to hijack research to market their treatments.

At the other extreme are trials that are little more than shots in the dark. In one case, patients with spinal cord injury were enrolled in a safety trial testing a cell-based regenerative medicine treatment. After the trial stopped (results were negative), laboratory scientists revealed that the cells had been shown ineffective in animal experiments. Though this information had been available to the company and FDA, researchers pursued the trial anyway.

It is surprisingly easy for companies to hijack research to market their treatments. One way this happens is through "seeding trials"- studies that are designed not to address a research question, but instead to habituate doctors to using a new drug and to generate publications that serve as advertisements. Such trials flood the medical literature with findings that are unreliable because studies are small and not well designed. They also use the prestige of science to pursue goals that are purely commercial. Yet because they harm science- not patients (many such studies are minimally risky because all patients receive proven effective medications)- ethics committees rarely block them.

Closely related is the phenomenon of small uninformative trials. After drugs get approved by the FDA, companies often launch dozens of small trials in new diseases other than the one the drug was approved to treat. Because these studies are small, they often overestimate efficacy. Indeed, the way trials are often set up, if a company tests an ineffective drug in 40 different studies, one will typically produce a false positive by chance alone. Because companies are free to run as many trials as they like and to circulate "positive" results, they have incentives to run lots of small trials that don't provide a definitive test of their drug's efficacy.

Universities, funding bodies, and companies should be scored by a neutral third-party based on the impact of their trials -- like Moody's for credit ratings.

Don't think public agencies are much better. Funders like the National Institutes of Health secure their appropriations by gratifying Congress. This means that NIH gets more by spreading its funding among small studies in different Congressional districts than by concentrating budgets among a few research institutions pursuing large trials. The result is that some NIH-funded clinical trials are not especially equipped to inform medical practice.

It's tempting to think that FDA, medical journals, ethics committees, and funding agencies can fix these problems. However, these practices continue in part because FDA, ethics committees, and researchers often do not see what is at stake for patients by acquiescing to low scientific standards. This behavior dishonors the patients who volunteer for research, and also threatens the welfare of downstream patients, whose care will be determined by the output of research.

To fix this, deficiencies in study design and reporting need to be rendered visible. Universities, funding bodies, and companies should be scored by a neutral third-party based on the impact of their trials, or the extent to which their trials are published in full -- like Moody's for credit ratings, or the Kelley Blue Book for cars. This system of accountability would allow everyone to see which institutions make the most of the contributions of research subjects. It could also harness the competitive instincts of institutions to improve research quality.

Another step would be for researchers to level with patients when they enroll in studies. Patients who agree to research are usually offered bromides about how their participation may help future patients. However, not all studies are created equal with respect to merit. Patients have a right to know when they are entering studies that are unlikely to have a meaningful impact on medicine.

Ethics committees and drug regulators have done a good job protecting research volunteers from unchecked scientific ambition. However, today's research is plagued by studies that have poor scientific credentials. Such studies free-ride on the well-earned reputation of serious medical science. They also potentially distort the evidence available to physicians and healthcare systems. Regulators, academic medical centers, and others should establish policies that better protect human research volunteers by protecting the quality of the research itself.

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

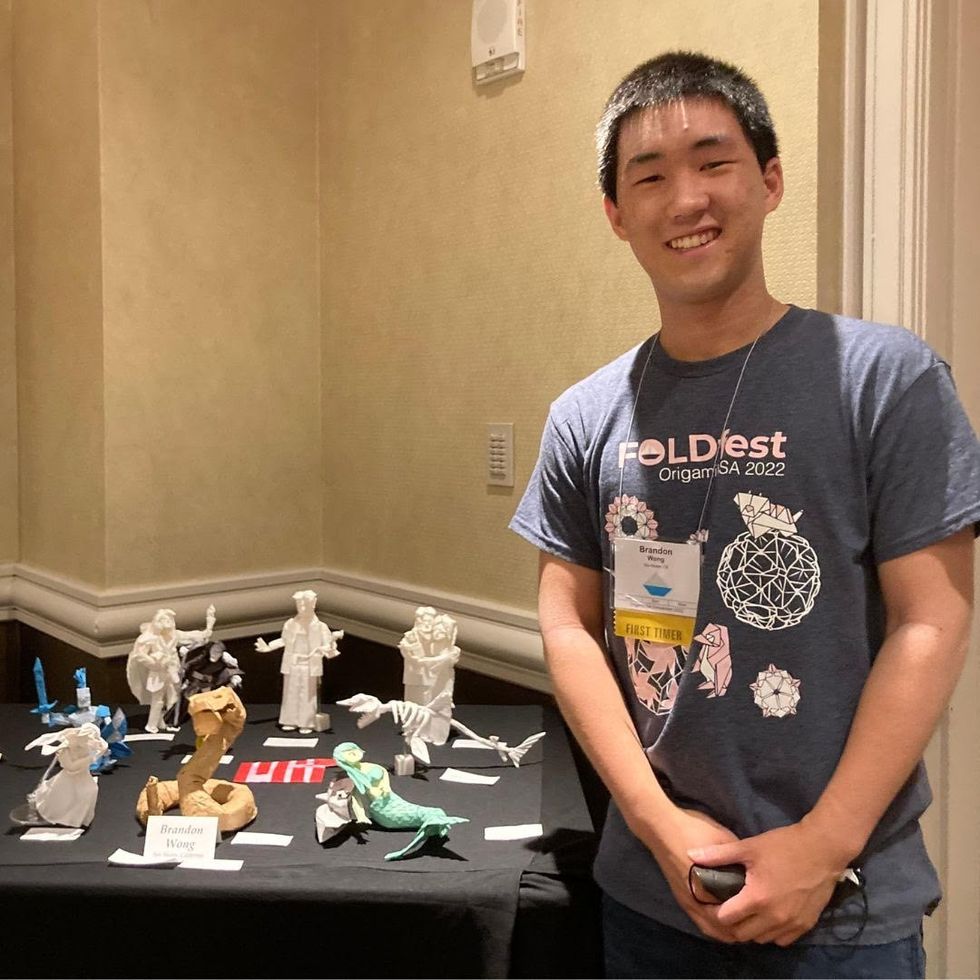

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”