Scientists are making machines, wearable and implantable, to act as kidneys

Recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon.

Like all those whose kidneys have failed, Scott Burton’s life revolves around dialysis. For nearly two decades, Burton has been hooked up (or, since 2020, has hooked himself up at home) to a dialysis machine that performs the job his kidneys normally would. The process is arduous, time-consuming, and expensive. Except for a brief window before his body rejected a kidney transplant, Burton has depended on machines to take the place of his kidneys since he was 12-years-old. His whole life, the 39-year-old says, revolves around dialysis.

“Whenever I try to plan anything, I also have to plan my dialysis,” says Burton says, who works as a freelance videographer and editor. “It’s a full-time job in itself.”

Many of those on dialysis are in line for a kidney transplant that would allow them to trade thrice-weekly dialysis and strict dietary limits for a lifetime of immunosuppressants. Burton’s previous transplant means that his body will likely reject another donated kidney unless it matches perfectly—something he’s not counting on. It’s why he’s enthusiastic about the development of artificial kidneys, small wearable or implantable devices that would do the job of a healthy kidney while giving users like Burton more flexibility for traveling, working, and more.

Still, the devices aren’t ready for testing in humans—yet. But recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen soon, according to Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington.

“It would liberate people with kidney failure,” Himmelfarb says.

An engineering marvel

Compared to the heart or the brain, the kidney doesn’t get as much respect from the medical profession, but its job is far more complex. “It does hundreds of different things,” says UCLA’s Ira Kurtz.

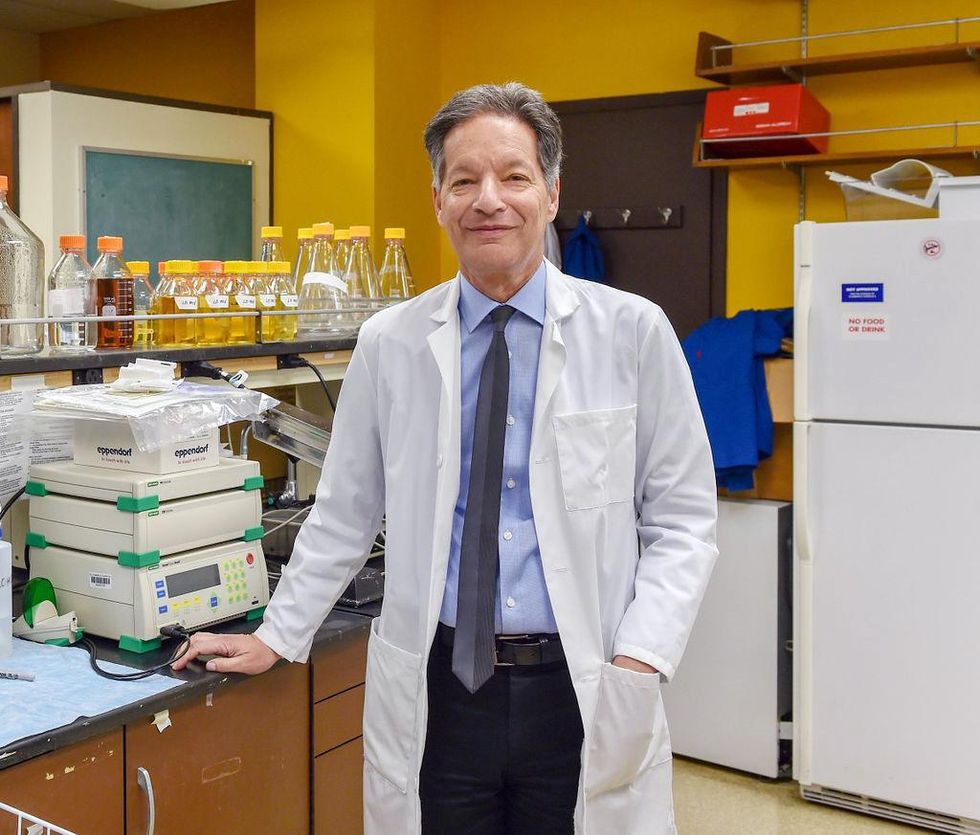

Kurtz would know. He’s worked as a nephrologist for 37 years, devoting his career to helping those with kidney disease. While his colleagues in cardiology and endocrinology have seen major advances in the development of artificial hearts and insulin pumps, little has changed for patients on hemodialysis. The machines remain bulky and require large volumes of a liquid called dialysate to remove toxins from a patient’s blood, along with gallons of purified water. A kidney transplant is the next best thing to someone’s own, functioning organ, but with over 600,000 Americans on dialysis and only about 100,000 kidney transplants each year, most of those in kidney failure are stuck on dialysis.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. To build an artificial heart, Kurtz says, you basically need to engineer a pump. An artificial pancreas needs to balance blood sugar levels with insulin secretion. While neither of these tasks is simple, they are fairly straightforward. The kidney, on the other hand, does more than get rid of waste products like urea and other toxins. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different, helping to regulate electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorous; maintaining blood pressure and water balance; guiding the body’s hormonal and inflammatory responses; and aiding in the formation of red blood cells.

There's been little progress for patients during Ira Kurtz's 37 years as a nephrologist. Artificial kidneys would change that.

UCLA

Dialysis primarily filters waste, and does so well enough to keep someone alive, but it isn’t a true artificial kidney because it doesn’t perform the kidney’s other jobs, according to Kurtz, such as sensing levels of toxins, wastes, and electrolytes in the blood. Due to the size and water requirements of existing dialysis machines, the equipment isn’t portable. Physicians write a prescription for a certain duration of dialysis and assess how well it’s working with semi-regular blood tests. The process of dialysis itself, however, is conducted blind. Doctors can’t tell how much dialysis a patient needs based on kidney values at the time of treatment, says Meera Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

But it’s the impact of dialysis on their day-to-day lives that creates the most problems for patients. Only one-quarter of those on dialysis are able to remain employed (compared to 85% of similar-aged adults), and many report a low quality of life. Having more flexibility in life would make a major different to her patients, Harhay says.

“Almost half their week is taken up by the burden of their treatment. It really eats away at their freedom and their ability to do things that add value to their life,” she says.

Art imitates life

The challenge for artificial kidney designers was how to compress the kidney’s natural functions into a portable, wearable, or implantable device that wouldn’t need constant access to gallons of purified and sterilized water. The other universal challenge they faced was ensuring that any part of the artificial kidney that would come in contact with blood was kept germ-free to prevent infection.

As part of the 2021 KidneyX Prize, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, inventors were challenged to create prototypes for artificial kidneys. Himmelfarb’s team at the University of Washington’s Center for Dialysis Innovation won the prize by focusing on miniaturizing existing technologies to create a portable dialysis machine. The backpack sized AKTIV device (Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality) will recycle dialysate in a closed loop system that removes urea from blood and uses light-based chemical reactions to convert the urea to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, which allows the dialysate to be recirculated.

Himmelfarb says that the AKTIV can be used when at home, work, or traveling, which will give users more flexibility and freedom. “If you had a 30-pound device that you could put in the overhead bins when traveling, you could go visit your grandkids,” he says.

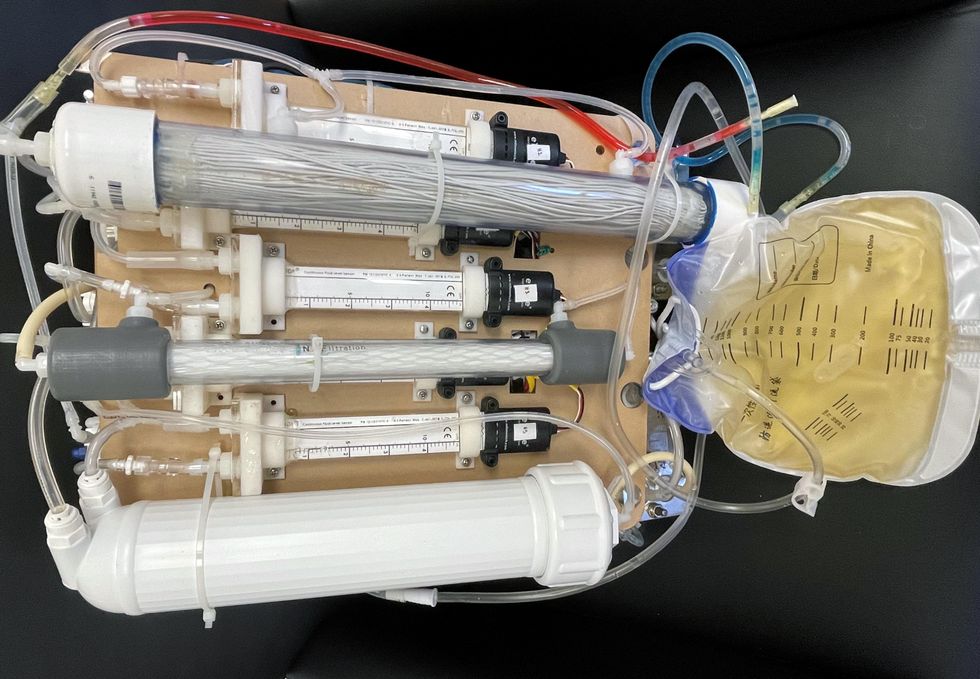

Kurtz’s team at UCLA partnered with the U.S. Kidney Research Corporation and Arkansas University to develop a dialysate-free desktop device (about the size of a small printer) as the first phase of a progression that will he hopes will lead to something small and implantable. Part of the reason for the artificial kidney’s size, Kurtz says, is the number of functions his team are cramming into it. Not only will it filter urea from blood, but it will also use electricity to help regulate electrolyte levels in a process called electrodeionization. Kurtz emphasizes that these additional functions are what makes his design a true artificial kidney instead of just a small dialysis machine.

One version of an artificial kidney.

UCLA

“It doesn't have just a static function. It has a bank of sensors that measure chemicals in the blood and feeds that information back to the device,” Kurtz says.

Other startups are getting in on the game. Nephria Bio, a spinout from the South Korean-based EOFlow, is working to develop a wearable dialysis device, akin to an insulin pump, that uses miniature cartridges with nanomaterial filters to clean blood (Harhay is a scientific advisor to Nephria). Ian Welsford, Nephria’s co-founder and CTO, says that the device’s design means that it can also be used to treat acute kidney injuries in resource-limited settings. These potentials have garnered interest and investment in artificial kidneys from the U.S. Department of Defense.

For his part, Burton is most interested in an implantable device, as that would give him the most freedom. Even having a regular outpatient procedure to change batteries or filters would be a minor inconvenience to him.

“Being plugged into a machine, that’s not mimicking life,” he says.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on May 5, 2022.

The Friday Five: A new blood test to detect Alzheimer's

A new blood test has been developed to detect Alzheimer's. Other promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five include: vets with PTSD can take their psychologist anywhere with a new device, intermittent fasting could improve circadian rhythms, a new year's resolution for living longer, and a discovery in 3-D printing eye tissue.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- A blood test to detect Alzheimer's

- War vets can take their psychologist wherever they go

- Does intermittent fasting affect circadian rhythms?

- A new year's resolution for living longer

- 3-D printed eyes?

Staying well in the 21st century is like playing a game of chess

The control of infectious diseases was considered to be one of the “10 Great Public Health Achievements.” What we didn’t take into account was the very concept of evolution: as we built better protections, our enemies eventually boosted their attacking prowess, so soon enough we found ourselves on the defensive once again.

This article originally appeared in One Health/One Planet, a single-issue magazine that explores how climate change and other environmental shifts are increasing vulnerabilities to infectious diseases by land and by sea. The magazine probes how scientists are making progress with leaders in other fields toward solutions that embrace diverse perspectives and the interconnectedness of all lifeforms and the planet.

On July 30, 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report comparing data on the control of infectious disease from the beginning of the 20th century to the end. The data showed that deaths from infectious diseases declined markedly. In the early 1900s, pneumonia, tuberculosis and diarrheal diseases were the three leading killers, accounting for one-third of total deaths in the U.S.—with 40 percent being children under five.

Mass vaccinations, the discovery of antibiotics and overall sanitation and hygiene measures eventually eradicated smallpox, beat down polio, cured cholera, nearly rid the world of tuberculosis and extended the U.S. life expectancy by 25 years. By 1997, there was a shift in population health in the U.S. such that cancer, diabetes and heart disease were now the leading causes of death.

The control of infectious diseases is considered to be one of the “10 Great Public Health Achievements.” Yet on the brink of the 21st century, new trouble was already brewing. Hospitals were seeing periodic cases of antibiotic-resistant infections. Novel viruses, or those that previously didn’t afflict humans, began to emerge, causing outbreaks of West Nile, SARS, MERS or swine flu.In the years that followed, tuberculosis made a comeback, at least in certain parts of the world. What we didn’t take into account was the very concept of evolution: as we built better protections, our enemies eventually boosted their attacking prowess, so soon enough we found ourselves on the defensive once again.

At the same time, new, previously unknown or extremely rare disorders began to rise, such as autoimmune or genetic conditions. Two decades later, scientists began thinking about health differently—not as a static achievement guaranteed to last, but as something dynamic and constantly changing—and sometimes, for the worse.

What emerged since then is a different paradigm that makes our interactions with the microbial world more like a biological chess match, says Victoria McGovern, a biochemist and program officer for the Burroughs Wellcome Fund’s Infectious Disease and Population Sciences Program. In this chess game, humans may make a clever strategic move, which could involve creating a new vaccine or a potent antibiotic, but that advantage is fleeting. At some point, the organisms we are up against could respond with a move of their own—such as developing resistance to medication or genetic mutations that attack our bodies. Simply eradicating the “opponent,” or the pathogenic microbes, as efficiently as possible isn’t enough to keep humans healthy long-term.

Instead, scientists should focus on studying the complexity of interactions between humans and their pathogens. “We need to better understand the lifestyles of things that afflict us,” McGovern says. “The solutions are going to be in understanding various parts of their biology so we can influence how they behave around our systems.”

Genetics and cell biology, combined with imaging techniques that allow one to see tissues and individual cells in actions, will enable scientists to define and quantify what it means to be healthy at the molecular level.

What is being proposed will require a pivot to basic biology and other disciplines that have suffered from lack of research funding in recent years. Yet, according to McGovern, the research teams of funded proposals are answering bigger questions. “We look for people exploring questions about hosts and pathogens, and what happens when they touch, but we’re also looking for people with big ideas,” she says. For example, if one specific infection causes a chain of pathological events in the body, can other infections cause them too? And if we find a way to break that chain for one pathogen, can we play the same trick on another? “We really want to see people thinking of not just one experiment but about big implications of their work,” McGovern says.

Jonah Cool, a cell biologist, geneticist and science officer at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, says that it’s necessary to define what constitutes a healthy organism and how it overcomes infections or environmental assaults, such as pollution from forest fires or toxins from industrial smokestacks. An organism that catches a disease isn’t necessarily an unhealthy one, as long as it fights it off successfully—an ability that arises from the complex interplay of its genes, the immune system, age, stress levels and other factors. Modern science allows many of these factors to be measured, recorded and compared. “We need a data-driven, deep-phenotyping approach to defining healthy biological systems and their responses to insults—which can be infectious disease or environmental exposures—and their ability to navigate their way through that space,” Cool says.

Genetics and cell biology, combined with imaging techniques that allow one to see tissues and individual cells in actions, will enable scientists to define and quantify what it means to be healthy at the molecular level. “As a geneticist and cell biologist, I believe in all these molecular underpinnings and how they arise in phenotypic differences in cells, genes, proteins—and how their combinations form complex cellular states,” Cool says.

Julie Graves, a physician, public health consultant, former adjunct professor of management, policy and community health at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, stresses the necessity of nutritious diets. According to the Rockefeller Food Initiative, “poor diet is the leading risk factor for disease, disability and premature death in the majority of countries around the world.” Adequate nutrition is critical for maintaining human health and life. Yet, Western diets are often low in essential nutrients, high in calories and heavy on processed foods. Overconsumption of these foods has contributed to high rates of obesity and chronic disease in the U.S. In fact, more than half of American adults have at least one chronic disease, and 27 percent have more than one—which increases vulnerability to COVID-19 infections, according to the 2018 National Health Interview Survey.

Further, the contamination of our food supply with various agricultural and industrial toxins—petrochemicals, pesticides, PFAS and others—has implications for morbidity, mortality, and overall quality of life. “These chemicals are insidiously in everything, including our bodies,” Graves says—and they are interfering with our normal biological functions. “We need to stop how we manufacture food,” she adds, and rid our sustenance of these contaminants.

According to the Humane Society of the United States, factory farms result in nearly 40 percent of emissions of methane. Concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs may serve as breeding grounds for pandemics, scientists warn, so humans should research better ways to raise and treat livestock. Diego Rose, a professor of food and nutrition policy at Tulane University School of Public Health & Tropical Medicine, and his colleagues found that “20 percent of Americans’ diets account for about 45 percent of the environmental impacts [that come from food].” A subsequent study explored the impacts of specific foods and found that substituting beef for chicken lowers an individual’s carbon footprint by nearly 50 percent, with water usage decreased by 30 percent. Notably, however, eating too much red meat has been associated with a variety of illnesses.

In some communities, the option to swap food types is limited or impossible. For example, “many populations live in relative food deserts where there’s not a local grocery store that has any fresh produce,” says Louis Muglia, the president and CEO of Burroughs Wellcome. Individuals in these communities suffer from an insufficient intake of beneficial macronutrients, and they’re “probably being exposed to phenols and other toxins that are in the packaging.” An equitable, sustainable and nutritious food supply will be vital to humanity’s wellbeing in the era of climate change, unpredictable weather and spillover events.

A recent report by See Change Institute and the Climate Mental Health Network showed that people who are experiencing socioeconomic inequalities, including many people of color, contribute the least to climate change, yet they are impacted the most. For example, people in low-income communities are disproportionately exposed to vehicle emissions, Muglia says. Through its Climate Change and Human Health Seed Grants program, Burroughs Wellcome funds research that aims to understand how various factors related to climate change and environmental chemicals contribute to premature births, associated with health vulnerabilities over the course of a person’s life—and map such hot spots.

“It’s very complex, the combinations of socio-economic environment, race, ethnicity and environmental exposure, whether that’s heat or toxic chemicals,” Muglia explains. “Disentangling those things really requires a very sophisticated, multidisciplinary team. That’s what we’ve put together to describe where these hotspots are and see how they correlate with different toxin exposure levels.”

In addition to mapping the risks, researchers are developing novel therapeutics that will be crucial to our armor arsenal, but we will have to be smarter at designing and using them. We will need more potent, better-working monoclonal antibodies. Instead of directly attacking a pathogen, we may have to learn to stimulate the immune system—training it to fight the disease-causing microbes on its own. And rather than indiscriminately killing all bacteria with broad-scope drugs, we would need more targeted medications. “Instead of wiping out the entire gut flora, we will need to come up with ways that kill harmful bacteria but not healthy ones,” Graves says. Training our immune systems to recognize and react to pathogens by way of vaccination will keep us ahead of our biological opponents, too. “Continued development of vaccines against infectious diseases is critical,” says Graves.

With all of the unpredictable events that lie ahead, it is difficult to foresee what achievements in public health will be reported at the end of the 21st century. Yet, technological advances, better modeling and pursuing bigger questions in science, along with education and working closely with communities will help overcome the challenges. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative displays an optimistic message on its website: “Is it possible to cure, prevent, or manage all diseases by the end of this century? We think so.” Cool shares the view of his employer—and believes that science can get us there. Just give it some time and a chance. “It’s a big, bold statement,” he says, “but the end of the century is a long way away.”Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.