Scientists are making machines, wearable and implantable, to act as kidneys

Recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen as soon as 18 months from now

Like all those whose kidneys have failed, Scott Burton’s life revolves around dialysis. For nearly two decades, Burton has been hooked up (or, since 2020, has hooked himself up at home) to a dialysis machine that performs the job his kidneys normally would. The process is arduous, time-consuming, and expensive. Except for a brief window before his body rejected a kidney transplant, Burton has depended on machines to take the place of his kidneys since he was 12-years-old. His whole life, the 39-year-old says, revolves around dialysis.

“Whenever I try to plan anything, I also have to plan my dialysis,” says Burton says, who works as a freelance videographer and editor. “It’s a full-time job in itself.”

Many of those on dialysis are in line for a kidney transplant that would allow them to trade thrice-weekly dialysis and strict dietary limits for a lifetime of immunosuppressants. Burton’s previous transplant means that his body will likely reject another donated kidney unless it matches perfectly—something he’s not counting on. It’s why he’s enthusiastic about the development of artificial kidneys, small wearable or implantable devices that would do the job of a healthy kidney while giving users like Burton more flexibility for traveling, working, and more.

Still, the devices aren’t ready for testing in humans—yet. But recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen as soon as 18 months from now, according to Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington.

“It would liberate people with kidney failure,” Himmelfarb says.

An engineering marvel

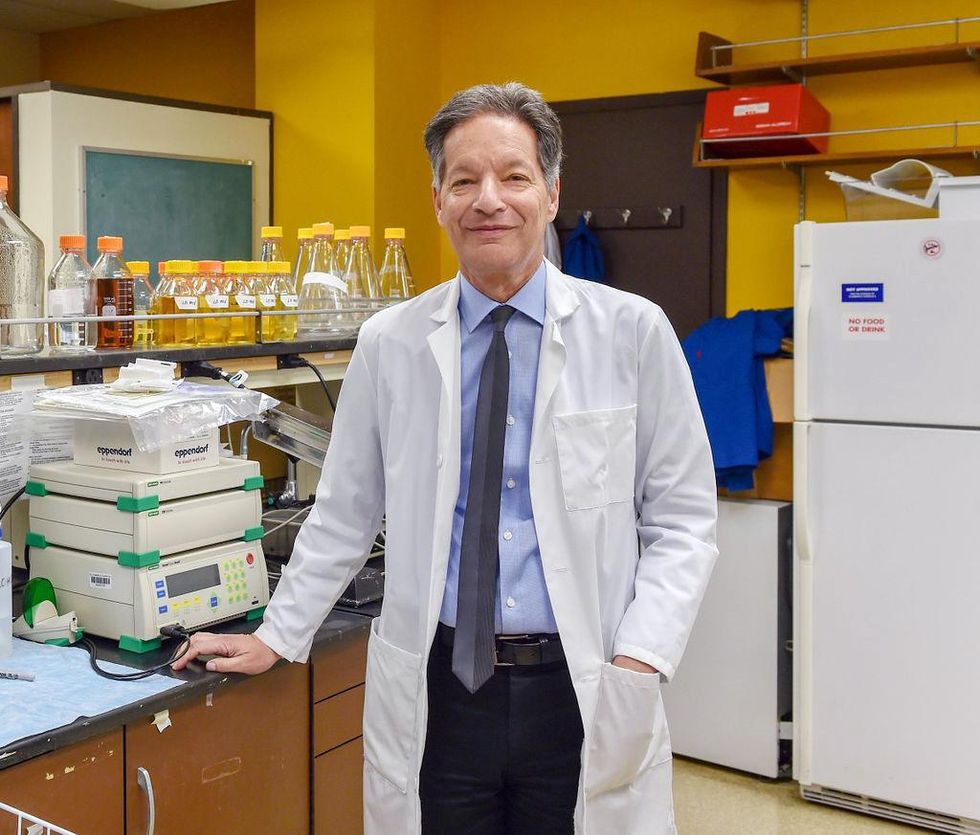

Compared to the heart or the brain, the kidney doesn’t get as much respect from the medical profession, but its job is far more complex. “It does hundreds of different things,” says UCLA’s Ira Kurtz.

Kurtz would know. He’s worked as a nephrologist for 37 years, devoting his career to helping those with kidney disease. While his colleagues in cardiology and endocrinology have seen major advances in the development of artificial hearts and insulin pumps, little has changed for patients on hemodialysis. The machines remain bulky and require large volumes of a liquid called dialysate to remove toxins from a patient’s blood, along with gallons of purified water. A kidney transplant is the next best thing to someone’s own, functioning organ, but with over 600,000 Americans on dialysis and only about 100,000 kidney transplants each year, most of those in kidney failure are stuck on dialysis.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. To build an artificial heart, Kurtz says, you basically need to engineer a pump. An artificial pancreas needs to balance blood sugar levels with insulin secretion. While neither of these tasks is simple, they are fairly straightforward. The kidney, on the other hand, does more than get rid of waste products like urea and other toxins. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different, helping to regulate electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorous; maintaining blood pressure and water balance; guiding the body’s hormonal and inflammatory responses; and aiding in the formation of red blood cells.

There's been little progress for patients during Ira Kurtz's 37 years as a nephrologist. Artificial kidneys would change that.

UCLA

Dialysis primarily filters waste, and does so well enough to keep someone alive, but it isn’t a true artificial kidney because it doesn’t perform the kidney’s other jobs, according to Kurtz, such as sensing levels of toxins, wastes, and electrolytes in the blood. Due to the size and water requirements of existing dialysis machines, the equipment isn’t portable. Physicians write a prescription for a certain duration of dialysis and assess how well it’s working with semi-regular blood tests. The process of dialysis itself, however, is conducted blind. Doctors can’t tell how much dialysis a patient needs based on kidney values at the time of treatment, says Meera Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

But it’s the impact of dialysis on their day-to-day lives that creates the most problems for patients. Only one-quarter of those on dialysis are able to remain employed (compared to 85% of similar-aged adults), and many report a low quality of life. Having more flexibility in life would make a major different to her patients, Harhay says.

“Almost half their week is taken up by the burden of their treatment. It really eats away at their freedom and their ability to do things that add value to their life,” she says.

Art imitates life

The challenge for artificial kidney designers was how to compress the kidney’s natural functions into a portable, wearable, or implantable device that wouldn’t need constant access to gallons of purified and sterilized water. The other universal challenge they faced was ensuring that any part of the artificial kidney that would come in contact with blood was kept germ-free to prevent infection.

As part of last year’s KidneyX Prize, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, inventors were challenged to create prototypes for artificial kidneys. Himmelfarb’s team at the University of Washington’s Center for Dialysis Innovation won the prize by focusing on miniaturizing existing technologies to create a portable dialysis machine. The backpack sized AKTIV device (Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality) will recycle dialysate in a closed loop system that removes urea from blood and uses light-based chemical reactions to convert the urea to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, which allows the dialysate to be recirculated.

Himmelfarb says that the AKTIV can be used when at home, work, or traveling, which will give users more flexibility and freedom. “If you had a 30-pound device that you could put in the overhead bins when traveling, you could go visit your grandkids,” he says.

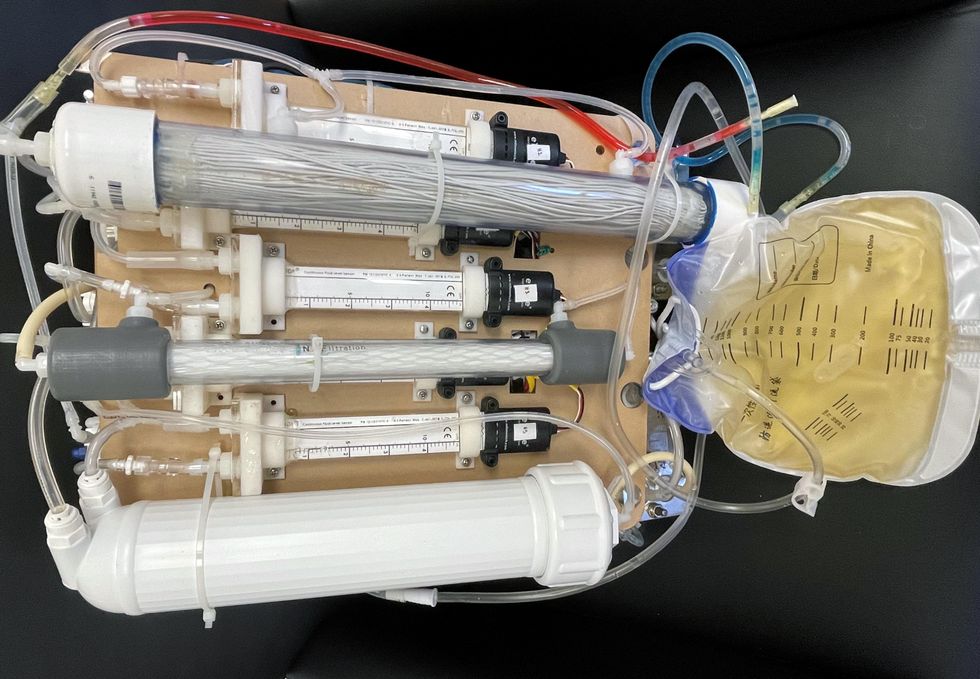

Kurtz’s team at UCLA partnered with the U.S. Kidney Research Corporation and Arkansas University to develop a dialysate-free desktop device (about the size of a small printer) as the first phase of a progression that will he hopes will lead to something small and implantable. Part of the reason for the artificial kidney’s size, Kurtz says, is the number of functions his team are cramming into it. Not only will it filter urea from blood, but it will also use electricity to help regulate electrolyte levels in a process called electrodeionization. Kurtz emphasizes that these additional functions are what makes his design a true artificial kidney instead of just a small dialysis machine.

One version of an artificial kidney.

UCLA

“It doesn't have just a static function. It has a bank of sensors that measure chemicals in the blood and feeds that information back to the device,” Kurtz says.

Other startups are getting in on the game. Nephria Bio, a spinout from the South Korean-based EOFlow, is working to develop a wearable dialysis device, akin to an insulin pump, that uses miniature cartridges with nanomaterial filters to clean blood (Harhay is a scientific advisor to Nephria). Ian Welsford, Nephria’s co-founder and CTO, says that the device’s design means that it can also be used to treat acute kidney injuries in resource-limited settings. These potentials have garnered interest and investment in artificial kidneys from the U.S. Department of Defense.

For his part, Burton is most interested in an implantable device, as that would give him the most freedom. Even having a regular outpatient procedure to change batteries or filters would be a minor inconvenience to him.

“Being plugged into a machine, that’s not mimicking life,” he says.

If approved by the FDA, a new procedure for kidney transplants that doesn't require anti-rejection medication could soon become the standard of care.

Talaris Therapeutics, Inc., a biotech company based in Louisville, Ky., is edging closer to eradicating the need for immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplant patients.

In a series of research trials, Talaris is infusing patients with immune system stem cells from their kidney donor to create a donor-derived immune system that accepts the organ without the need for anti-rejection medications. That newly generated system does not attack other parts of the recipient’s body and also fights off infections and diseases as a healthy immune system would.

Talaris is now moving into the final clinical trial, phase III, before submitting for FDA approval. Known as Freedom-1, this trial has 17 sites open throughout the U.S., and Talaris will enroll a total of 120 kidney transplant recipients. One day after receiving their donor’s kidney, 80 people will undergo the company’s therapy, involving the donor’s stem cells and other critical cells that are processed at their facility. Forty will have a regular kidney transplant and remain on immunosuppression to provide a control group.

“The beauty of this procedure is that I don’t have to take all of the anti-rejection drugs,” says Robert Waddell, a finance professional. “I forget that I ever had any kidney issues. That’s how impactful it is.”

The procedure was pioneered decades ago by Suzanne Ildstad as a faculty member at the University of Pittsburgh before she became founding CEO of Talaris and then its Chief Scientific Officer. If approved by the FDA, the method could soon become the standard of care for patients in need of a kidney transplant.

“We are working to find a way to reprogram the immune system of transplant recipients so that it sees the donated organ as [belonging to one]self and doesn’t attack it,” explains Scott Requadt, CEO of Talaris. “That obviates the need for lifelong immunosuppression.”

Each year, there are roughly 20,000 kidney transplants, making kidneys the most transplanted organ. About 6,500 of those come from living donors, while deceased donors provide roughly 13,000.

One of the challenges, Requadt points out, is that kidney transplant recipients aren’t always aware of all the implications of immunosuppression. Typically, they will need to take about 20 anti-rejection drugs several times a day to provide immunosuppression as well as treat complications caused by the toxicities of immunosuppression medications. The side effects of chronic immunosuppression include weight gain, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. These cardiovascular comorbidities, Requadt says, are “often more frequently the cause of death than failure of a transplanted organ.”

Patients who are chronically immunosuppressed generally have much higher rates of infections and cancers that have an immune component to them, such as skin cancers.

For the past couple of years, those patients have experienced heightened anxiety because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Immune-suppressing medicine used to protect their new organ also makes it hard for patients to build immunity to foreign invaders like COVID-19.

A study appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found the probability of a pandemic with similar impact to COVID-19 is about 2 percent in any year, and estimated that the probability of novel disease outbreaks will grow three-fold in the next few decades. All the more reason to identify an FDA-approved alternative to harsh immunosuppressive drugs.

Of the 18 patients during the phase II research trial who received the Talaris therapy, didn’t take immunosuppression medication and were vaccinated, only two ended up with a COVID infection, according to a review of the data. Among patients who needed to continue taking immunosuppressants or those who didn’t have them but were unvaccinated, the rates of infection were between 40 and 60 percent.

In the earlier phase II study by Talaris with 37 patients, the combined transplantation approach allowed 70 percent of patients to get off all immunosuppression.

“We’ve followed that whole cohort for more than six and a half years and one of them for 12 years from transplant, and every single patient that we got off immunosuppression has been able to stay off,” Requadt says.

That one patient, Robert Waddell, 55, was especially thankful to be weaned off immunosuppressive drugs approximately one year after his transplant procedure. The Louisville resident had long watched his mother, sister and other family members with polycystic kidney disease, or PKD, suffer the effects of chronic immunosuppression. That became his greatest fear when he was diagnosed with end stage renal failure.

Waddell enrolled in the phase II research taking place in Louisville after learning about it in early 2006. He chose to remain in the study when it relocated its clinical headquarters to Northwestern University’s medical center in Chicago a couple years later.

Before surgery, he underwent an enervating regimen of chemotherapy and radiation. It’s required to clear out a patient’s bone marrow cells so that they can be replaced by the donor’s cells. Waddell says the result was worth it: he had his combined kidney and immune system stem cell transplant in May 2009, without any need for chronic immunosuppression.

“I call it ‘short-term pain, long-term gain,’ because it was difficult to go through the conditioning, but after that, it was great,” he says. “I’ve talked to so many kidney recipients who say, ‘I wish I would have done that,’ because most people don’t think about clinical trials, but I was very fortunate.”

Waddell has every reason to support the success of this research, especially given the genetic disorder, PKD, that has plagued his family. One of his four children has PKD. He is anxious for the procedure to become standard of care, if and when his son needs it.

The Talaris procedure was pioneered decades ago by Suzanne Ildstad, founding CEO of Talaris and the company's Chief Scientific Officer, pictured here with the current CEO, Scott Requadt.

Talaris

“The beauty of this procedure is that I don’t have to take all of the anti-rejection drugs,” says Waddell, a finance professional. “I forget that I ever had any kidney issues. That’s how impactful it is.”

Talaris will continue to follow Waddell and the rest of his cohort to track the effectiveness and safety of the procedure. According to Requadt, the average life of a transplanted kidney is 12 to 15 years, partly because the immunosuppressive drugs worsen the functioning of the organ each year.

“We were the first group to show that we could robustly and fairly reproducibly do this in a clinical setting in humans,” Requadt says. “Most important, we’ve been able to show that we can still get a good engraftment of the stem cells from the donor, even if there is a profound…mismatch between the donor and the recipient’s immune systems.”

In kidney transplantation, it’s important to match for human leukocyte antigens (HLA) because there is a better graft survival in HLA-identical kidney transplants compared with HLA mismatched transplants.

About three months after the transplant, Talaris researchers look for evidence that the donated immune cells and stem cells have engrafted, while making a donor immune system for the patient. If more than 50 percent of the T cells contain the donor’s DNA after six months, patients can start taking fewer immunosuppressants.

“We know from phase II that in our patients who were able to tolerize [accept the organ without rejection] to their donated organ, we saw completely preserved and in fact slightly increased kidney function,” Requadt says. “So, it stands to reason that if you eliminate the drugs that are associated with declining kidney function that you would preserve kidney function, so hopefully the patient will have that one kidney for life.”

Matthew Cooper, director of kidney and pancreas transplantation for MedStar Georgetown Transplant Institute in Washington, DC, states that, “Right now, the Achilles’ heel is we have such a long waiting list and few donors that people die every day waiting for a kidney transplant. Eventually, we will eliminate the organ shortage so that people won’t die from organ failure.”

Cooper, a nationally recognized clinical transplant surgeon for 20 years, says when he started his career, finding a way for patients to forgo immunosuppression was considered “the Holy Grail” of modern transplant medicine.

“Now that we’ve got the protocols in place and some personal examples of how that can happen, it’s pretty exciting to see that all coming together,” he adds.

Researchers advance drugs that treat pain without addiction

New therapies are using creative approaches that target the body’s sensory neurons, which send pain signals to the brain.

Opioids are one of the most common ways to treat pain. They can be effective but are also highly addictive, an issue that has fueled the ongoing opioid crisis. In 2020, an estimated 2.3 million Americans were dependent on prescription opioids.

Opioids bind to receptors at the end of nerve cells in the brain and body to prevent pain signals. In the process, they trigger endorphins, so the brain constantly craves more. There is a huge risk of addiction in patients using opioids for chronic long-term pain. Even patients using the drugs for acute short-term pain can become dependent on them.

Scientists have been looking for non-addictive drugs to target pain for over 30 years, but their attempts have been largely ineffective. “We desperately need alternatives for pain management,” says Stephen E. Nadeau, a professor of neurology at the University of Florida.

A “dimmer switch” for pain

Paul Blum is a professor of biological sciences at the University of Nebraska. He and his team at Neurocarrus have created a drug called N-001 for acute short-term pain. N-001 is made up of specially engineered bacterial proteins that target the body’s sensory neurons, which send pain signals to the brain. The proteins in N-001 turn down pain signals, but they’re too large to cross the blood-brain barrier, so they don’t trigger the release of endorphins. There is no chance of addiction.

When sensory neurons detect pain, they become overactive and send pain signals to the brain. “We wanted a way to tone down sensory neurons but not turn them off completely,” Blum reveals. The proteins in N-001 act “like a dimmer switch, and that's key because pain is sensation overstimulated.”

Blum spent six years developing the drug. He finally managed to identify two proteins that form what’s called a C2C complex that changes the structure of a subunit of axons, the parts of neurons that transmit electrical signals of pain. Changing the structure reduces pain signaling.

“It will be a long path to get to a successful clinical trial in humans," says Stephen E. Nadeau, professor of neurology at the University of Florida. "But it presents a very novel approach to pain reduction.”

Blum is currently focusing on pain after knee and ankle surgery. Typically, patients are treated with anesthetics for a short time after surgery. But anesthetics usually only last for 4 to 6 hours, and long-term use is toxic. For some, the pain subsides. Others continue to suffer after the anesthetics have worn off and start taking opioids.

N-001 numbs sensation. It lasts for up to 7 days, much longer than any anesthetic. “Our goal is to prolong the time before patients have to start opioids,” Blum says. “The hope is that they can switch from an anesthetic to our drug and thereby decrease the likelihood they're going to take the opioid in the first place.”

Their latest animal trial showed promising results. In mice, N-001 reduced pain-like behaviour by 90 percent compared to the control group. One dose became effective in two hours and lasted a week. A high dose had pain-relieving effects similar to an opioid.

Professor Stephen P. Cohen, director of pain operations at John Hopkins, believes the Neurocarrus approach has potential but highlights the need to go beyond animal testing. “While I think it's promising, it's an uphill battle,” he says. “They have shown some efficacy comparable to opioids, but animal studies don't translate well to people.”

Nadeau, the University of Florida neurologist, agrees. “It will be a long path to get to a successful clinical trial in humans. But it presents a very novel approach to pain reduction.”

Blum is now awaiting approval for phase I clinical trials for acute pain. He also hopes to start testing the drug's effect on chronic pain.

Learning from people who feel no pain

Like Blum, a pharmaceutical company called Vertex is focusing on treating acute pain after surgery. But they’re doing this in a different way, by targeting a sodium channel that plays a critical role in transmitting pain signals.

In 2004, Stephen Waxman, a neurology professor at Yale, led a search for genetic pain anomalies and found that biologically related people who felt no pain despite fractures, burns and even childbirth had mutations in the Nav1.7 sodium channel. Further studies in other families who experienced no pain showed similar mutations in the Nav1.8 sodium channel.

Scientists set out to modify these channels. Many unsuccessful efforts followed, but Vertex has now developed VX-548, a medicine to inhibit Nav1.8. Typically, sodium ions flow through sodium channels to generate rapid changes in voltage which create electrical pulses. When pain is detected, these pulses in the Nav1.8 channel transmit pain signals. VX-548 uses small molecules to inhibit the channel from opening. This blocks the flow of sodium ions and the pain signal. Because Nav1.8 operates only in peripheral nerves, located outside the brain, VX-548 can relieve pain without any risk of addiction.

"Frankly we need drugs for chronic pain more than acute pain," says Waxman.

The team just finished phase II clinical trials for patients following abdominoplasty surgery and bunionectomy surgery.

After abdominoplasty surgery, 76 patients were treated with a high dose of VX-548. Researchers then measured its effectiveness in reducing pain over 48 hours, using the SPID48 scale, in which higher scores are desirable. The score for Vertex’s drug was 110.5 compared to 72.7 in the placebo group, whereas the score for patients taking an opioid was 85.2. The study involving bunionectomy surgery showed positive results as well.

Waxman, who has been at the forefront of studies into Nav1.7 and Nav1.8, believes that Vertex's results are promising, though he highlights the need for further clinical trials.

“Blocking Nav1.8 is an attractive target,” he says. “[Vertex is] studying pain that is relatively simple and uniform, and that's key to having a drug trial that is informative. But the study needs to be replicated and frankly we need drugs for chronic pain more than acute pain. If this is borne out by additional studies, it's one important step in a journey.”

Vertex will be launching phase III trials later this year.

Finding just the right amount of Nerve Growth Factor

Whereas Neurocarrus and Vertex are targeting short-term pain, a company called Levicept is concentrating on relieving chronic osteoarthritis pain. Around 32.5 million Americans suffer from osteoarthritis. Patients commonly take NSAIDs, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but they cannot be taken long-term. Some take opioids but they aren't very effective.

Levicept’s drug, Levi-04, is designed to modify a signaling pathway associated with pain. Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) is a neurotrophin: it’s involved in nerve growth and function. NGF signals by attaching to receptors. In pain there are excess neurotrophins attaching to receptors and activating pain signals.

“What Levi-04 does is it returns the natural equilibrium of neurotrophins,” says Simon Westbrook, the CEO and founder of Levicept. It stabilizes excess neurotrophins so that the NGF pathway does not signal pain. Levi-04 isn't addictive since it works within joints and in nerves outside the brain.

Westbrook was initially involved in creating an anti-NGF molecule for Pfizer called Tanezumab. At first, Tanezumab seemed effective in clinical trials and other companies even started developing their own versions. However, a problem emerged. Tanezumab caused rapidly progressive osteoarthritis, or RPOA, in some patients because it completely removed NGF from the system. NGF is not just involved in pain signalling, it’s also involved in bone growth and maintenance.

Levicept has found a way to modify the NGF pathway without completely removing NGF. They have now finished a small-scale phase I trial mainly designed to test safety rather than efficacy. “We demonstrated that Levi-04 is safe and that it bound to its target, NGF,” says Westbrook. It has not caused RPOA.

Professor Philip Conaghan, director of the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, believes that Levi-04 has potential but urges the need for caution. “At this early stage of development, their molecule looks promising for osteoarthritis pain,” he says. “They will have to watch out for RPOA which is a potential problem.”

Westbrook starts phase II trials with 500 patients this summer to check for potential side effects and test the drug’s efficacy.

There is a real push to find an effective alternative to opioids. “We have a lot of work to do,” says Professor Waxman. “But I am confident that we will be able to develop new, much more effective pain therapies.”