Lab-Grown Mini Kidneys Are Bringing Science Closer to Custom Organs

A model of a human kidney.

Science's dream of creating perfect custom organs on demand as soon as a patient needs one is still a long way off. But tiny versions are already serving as useful research tools and stepping stones toward full-fledged replacements.

Although organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, they are invaluable tools for research.

The Lowdown

Australian researchers have grown hundreds of mini human kidneys in the past few years. Known as organoids, they function much like their full-grown counterparts, minus a few features due to a lack of blood supply.

Cultivated in a petri dish, these kidneys are still a shadow of their human counterparts. They grow no larger than one-sixth of an inch in diameter; fully developed organs are up to five inches in length. They contain no more than a few dozen nephrons, the kidney's individual blood-filtering unit, whereas a fully-grown kidney has about 1 million nephrons. And the dish variety live for just a few weeks.

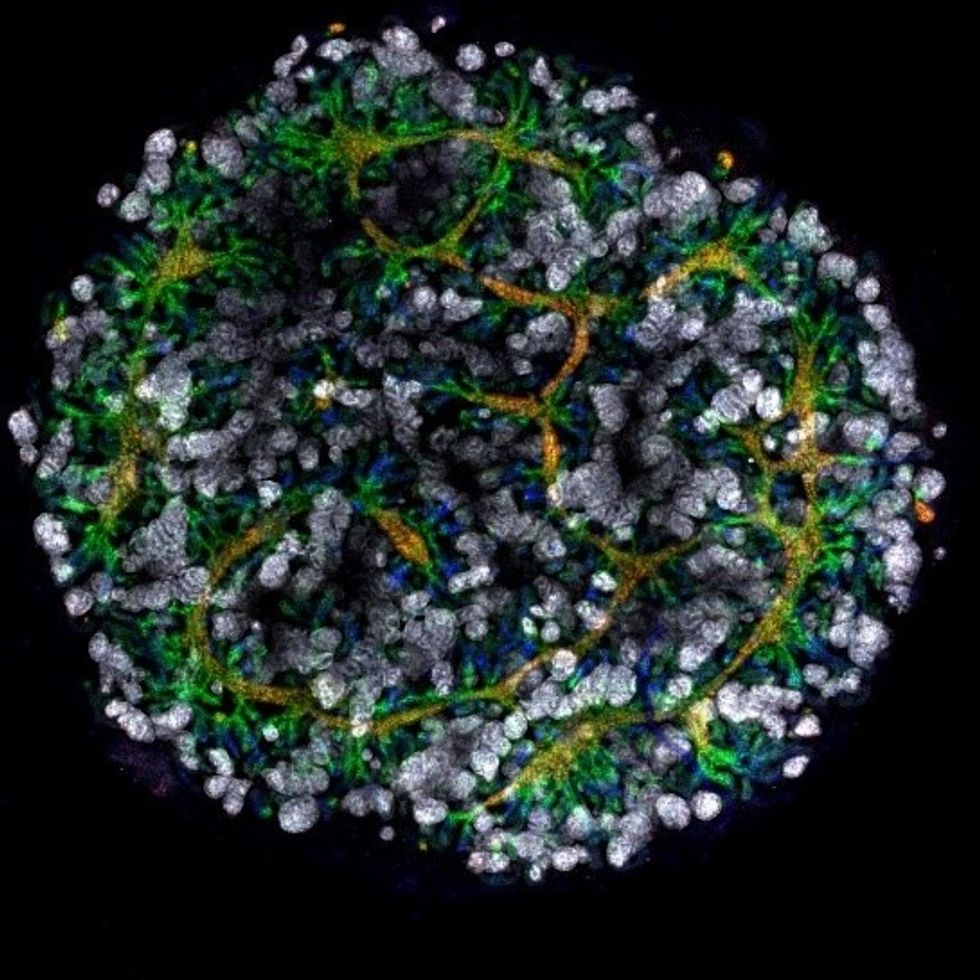

An organoid kidney created by the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo Credit: Shahnaz Khan.

But Melissa Little, head of the kidney research laboratory at the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, says these organoids are invaluable tools for research. Although renal failure is rare in children, more than half of those who suffer from such a disorder inherited it.

The mini kidneys enable scientists to better understand the progression of such disorders because they can be grown with a patient's specific genetic condition.

Mature stem cells can be extracted from a patient's blood sample and then reprogrammed to become like embryonic cells, able to turn into any type of cell in the body. It's akin to walking back the clock so that the cells regain unlimited potential for development. (The Japanese scientist who pioneered this technique was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2012.) These "induced pluripotent stem cells" can then be chemically coaxed to grow into mini kidneys that have the patient's genetic disorder.

"The (genetic) defects are quite clear in the organoids, and they can be monitored in the dish," Little says. To date, her research team has created organoids from 20 different stem cell lines.

Medication regimens can also be tested on the organoids, allowing specific tailoring for each patient. For now, such testing remains restricted to mice, but Little says it eventually will be done on human organoids so that the results can more accurately reflect how a given patient will respond to particular drugs.

Next Steps

Although these organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, Little says they may plug a huge gap in renal care by assisting in developing new treatments for chronic conditions. Currently, most patients with a serious kidney disorder see their options narrow to dialysis or organ transplantation. The former not only requires multiple sessions a week, but takes a huge toll on patient health.

Ten percent of older patients on dialysis die every year in the U.S. Aside from the physical trauma of organ transplantation, finding a suitable donor outside of a family member can be difficult.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells."

Meanwhile, the ongoing creation of organoids is supplying Little and her colleagues with enough information to create larger and more functional organs in the future. According to Little, researchers in the Netherlands, for example, have found that implanting organoids in mice leads to the creation of vascular growth, a potential pathway toward creating bigger and better kidneys.

And while Little acknowledges that creating a fully-formed custom organ is the ultimate goal, the mini organs are an important bridge step.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells, and I am just passionate to see it do some good."

MILESTONE: Doctors have transplanted a pig organ into a human for the first time in history

A surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital prepares a pig organ for transplant.

Surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital made history last week when they successfully transplanted a pig kidney into a human patient for the first time ever.

The recipient was a 62-year-old man named Richard Slayman who had been living with end-stage kidney disease caused by diabetes. While Slayman had received a kidney transplant in 2018 from a human donor, his diabetes ultimately caused the kidney to fail less than five years after the transplant. Slayman had undergone dialysis ever since—a procedure that uses an artificial kidney to remove waste products from a person’s blood when the kidneys are unable to—but the dialysis frequently caused blood clots and other complications that landed him in the hospital multiple times.

As a last resort, Slayman’s kidney specialist suggested a transplant using a pig kidney provided by eGenesis, a pharmaceutical company based in Cambridge, Mass. The highly experimental surgery was made possible with the Food and Drug Administration’s “compassionate use” initiative, which allows patients with life-threatening medical conditions access to experimental treatments.

The new frontier of organ donation

Like Slayman, more than 100,000 people are currently on the national organ transplant waiting list, and roughly 17 people die every day waiting for an available organ. To make up for the shortage of human organs, scientists have been experimenting for the past several decades with using organs from animals such as pigs—a new field of medicine known as xenotransplantation. But putting an animal organ into a human body is much more complicated than it might appear, experts say.

“The human immune system reacts incredibly violently to a pig organ, much more so than a human organ,” said Dr. Joren Madsen, director of the Mass General Transplant Center. Even with immunosuppressant drugs that suppress the body’s ability to reject the transplant organ, Madsen said, a human body would reject an animal organ “within minutes.”

So scientists have had to use gene-editing technology to change the animal organs so that they would work inside a human body. The pig kidney in Slayman’s surgery, for instance, had been genetically altered using CRISPR-Cas9 technology to remove harmful pig genes and add human ones. The kidney was also edited to remove pig viruses that could potentially infect a human after transplant.

With CRISPR technology, scientists have been able to prove that interspecies organ transplants are not only possible, but may be able to successfully work long term, too. In the past several years, scientists were able to transplant a pig kidney into a monkey and have the monkey survive for more than two years. More recently, doctors have transplanted pig hearts into human beings—though each recipient of a pig heart only managed to live a couple of months after the transplant. In one of the patients, researchers noted evidence of a pig virus in the man’s heart that had not been identified before the surgery and could be a possible explanation for his heart failure.

So far, so good

Slayman and his medical team ultimately decided to pursue the surgery—and the risk paid off. When the pig organ started producing urine at the end of the four-hour surgery, the entire operating room erupted in applause.

Slayman is currently receiving an infusion of immunosuppressant drugs to prevent the kidney from being rejected, while his doctors monitor the kidney’s function with frequent ultrasounds. Slayman is reported to be “recovering well” at Massachusetts General Hospital and is expected to be discharged within the next several days.Niklas Anzinger is the founder of Infinita VC based in the charter city of Prospera in Honduras. Infinita focuses on a new trend of charter cities and other forms of alternative jurisdictions. Healso hosts a podcast about how to accelerate the future by unblocking “stranded technologies”.This spring he was a part of the network city experiment Zuzalu spearheaded by Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin where a few hundred invited guests from the spheres of longevity, biotechnology, crypto, artificial intelligence and investment came together to form a two-monthlong community. It has been described as the world’s first pop-up city. Every morning Vitalians would descend on a long breakfast—the menu had been carefully designed by famed radical longevity self-experimenter Bryan Johnson—and there is where I first met Anzinger who told me about Prospera. Intrigued to say the least, I caught up with him later the same week and the following is a record of our conversation.

Q. We are sitting here in the so-called pop-up network state Zuzalu temporarily realized in the village of Lusticia Bay by the beautiful Mediterranean Sea. To me this is an entirely new concept: What is a network state?

A. A network state is a highly aligned online community that has a level of in-person civility; it crowd-funds territory, and it eventually seeks diplomatic recognition. In a way it's about starting a new country. The term was coined by the crypto influencer and former CTO of Coinbase Balaji Srinivasan in a book by the same title last year [2022]. What many people don't know is that it is a more recent addition or innovation in a space called competitive governance. The idea is that you have multiple jurisdictions competing to provide you services as a customer. When you have competition among governments or government service providers, these entities are forced to provide you with a better service instead of the often worse service at higher prices or higher taxes that we're currently getting. The idea went from seasteading, which was hardly feasible because of costs, to charter cities getting public/private partnerships with existing governments and a level of legal autonomy, to special economic zones, to now network states.

Q. How do network states compare to charter cities and similar jurisdictions?

A. Charter cities and special economic zones were legal forks from other existing states. Dubai, Shenzhen in China, to some degree Hong Kong, to some degree Singapore are some examples. There's a host of other charter cities, one of which I'm based in myself, which is Prospera located in Honduras on the island Roatán. Charter cities provide the full stack of governance; they provide new laws and regulations, business registration, tax codes and governance services, Estonia style: you log on to the government platform and you get services as a citizen.

When conceptualizing network states, Balagi Srinivasan turns the idea of a charter city a bit on its head: he doesn't want to start with this full stack because it's still very hard to get these kinds of partnerships with government. It's very expensive and requires lots of experience and lots of social capital. He is saying that network states could instead start as an online community. They could have a level of alignment where they trade with each other; they have their own economy; they meet in person in regular gatherings like we're doing here in Zuzulu for two months, and then they negotiate with existing governments or host cities to get a certain degree of legal autonomy that is centered around a moral innovation. So, his idea is: don't focus on building a completely new country or city; focus on a moral innovation.

Q. What would be an example of such a moral innovation?

A. An example would be longevity—life is good; death is bad—let's see what we can do to foster progress around that moral innovation and see how we can get legal forks from the existing system that allow us to accelerate progress in that area. There is an increasing realization in the science that there are hallmarks of aging and that aging is a cause of other diseases like cancer, ALS or Alzheimer's. But aging is not recognized as a disease by the FDA in the United States and in most countries around the world, so it's very hard to get scientific funding for biotechnology that would attack the hallmarks of aging and allow us potentially to reverse aging and extend life. This is a significant shortcoming of existing government systems that groups such as the ones that have come together here in Montenegro are now seeking alternatives too. Charter cities and now network states are such alternatives.

Q. Would it not be better to work within the current systems, and try to improve them, rather than abandon them for new experimental jurisdictions?

A. There are numerous failures of public policies. These failures are hard, if not impossible, to reverse, because as soon as you have these policies, you have entrenched interests who benefit from the regulations. The only way to disrupt incumbent industries is with start-ups, but the way the system is set up makes it excessively hard for such start-ups to become big companies. In fact, larger companies are weaponizing the legal system against small companies, because they can afford the lawyers and the fixed cost of compliance.

I don't believe that our institutions in many developed countries are beyond hope. I just think it's easier to change them if you could point at successful examples. ‘Hey, this country or this zone is already doing it very successfully’; if they can extend people’s lifespan by 10 years, if they can reduce maternal mortality, and if they have a massive medical tourism where people come back healthier, then that is just very embarrassing for the FDA.

Q. Perhaps a comparison here would be the relationship between Hong Kong and China?

A. Correct, so having Hong Kong right in front of your door … ‘Hey, this capitalism thing seems to work, why don't we try it here?’ It was due to the very bold leadership by Deng Xiaoping that they experimented with it in the development zone of Shenzhen. It worked really well and then they expanded with more special economic zones that also worked.

Próspera is a private city and special economic zone on the island of Roatán in the Central American state of Honduras.

Q. Tell us about Prospera, the charter city in Honduras, that you are intimately connected with.

A. Honduras is a very poor country. It has a lot of crime, never had a single VC investment, and has a GDP per capita of 2,000 per year. Honduras has suffered tremendously. The goal of these special economic zones is to bring in economic development. That's their sole purpose. It's a homegrown innovation from Honduras that started in 2009 with a very forward-thinking statesman, Octavio Sanchez, who was the chief of staff to the president of Honduras, and then president. He had his own ideas about making Honduras a more decentralized system, where more of the power lies in the municipalities.

Inspired by the ideas of Nobel laureate economist Paul Romer, who gave a famous Ted Talk in 2009 about charter cities, Sanchez initiated a process that lasted for years and eventually led to the creation of a special economic zone legal regime that’s anchored in the Hunduran constitution that provides the highest legal autonomy in the world to these zones. There are today three special economic zones approved by the Honduran government: Prospera, Ciudad Morazan and Orchidea.

Q. How did you become interested and then involved in Prospera?

A. I read about it first in an article by Scott Alexander, a famous rationalist blogger, who wrote a very long article about Prospera, and I thought, this is amazing! Then I came to Prospera and I found it to be one of the most if not the most exciting project in the world going on right now and that it also opened my heart to the country and its people. Most of my friends there are Honduran, they have been working on this for 10 or more years. They want to remake Honduras and put it on the map as the place in the world where this legal and governance innovation started.

Q. To what extent is Prospera autonomous relative to the Honduran government?

A. What's interesting about the Honduran model is that it's anchored within the Honduran constitution, and it has a very clear framework for what's possible and what's not possible, and what's possible ensures the highest degree of legal autonomy anywhere seen in the world. Prospera has really pushed the model furthest in creating a common law-based polycentric legal system. The idea is that you don't have a legislature, instead you have common law and it's based on the best practice common law principles that a legal scholar named Tom W. Bell created.

One of the core ideas is that as a business you're not obligated to follow one regulatory monopoly like the FDA. You have regulatory flexibility so you can choose what you're regulated under. So, you can say: ‘if I do a medical clinic, I do it under Norwegian law here’. And you even have the possibility to amend it a bit. You're still required to have liability insurance, and have to agree to binding arbitration in case there's a legal dispute. And your insurance has to approve you. So, under that model the insurance becomes the regulator and they regulate through prices. The limiting factor is criminal law; Honduran criminal law fully applies. So does immigration law. And we pay taxes.

Q. Is there also an idea of creating a kind of healthy living there, and encourage medical tourism?

A. Yes, we specifically look for legal advantages in autonomy around creating new drugs, doing clinical trials, doing self-medication and experimentation. There is a stem cell clinic here and they're doing clinical trials. The island of Roatán is very easily accessible for American tourists. It's a beautiful island, and it's for regulatory reasons hard to do stem cell therapies in the United States, so they're flying in patients from the United States. Most of them are very savvy and often have PhDs in biotech and are able to assess the risk for themselves of taking drugs and doing clinical trials. We're also going to get a wellness center, and there have been ideas around establishing a peptide clinic and a compound pharmacy and things like that. We are developing a healthcare ecosystem.

Q. This kind of experimental tourism raises some ethical issues. What happens if patients are harmed? And what are the moral implications for society of these new treatments?

A. As a moral principle we believe in medical freedom: people have rights over their bodies, even at the (informed) risk of harm to themselves if no unconsenting third-parties are harmed; this is a fundamental right currently not protected effectively.

What we do differently is not changing ethical norms around safety and efficacy, we’re just changing the institutional setup. Instead of one centralized bureaucracy, like the FDA, we have regulatory pluralism that allows different providers of safety and efficacy to compete under market rules. Like under any legal system, common law in Prospera punishes malpractice, fraud, murder etc. This system will still produce safe and effective drugs, and it will still work with common sense legal notions like informed consent and liability for harm. There are regulations for medical practice, there is liability insurance and things like that. It will just do so more efficiently than the current way of doing things (unless it won’t, in which case it will change and evolve – or fail).

A direct moral benefit ´to what we do is that we increase accessibility. Typical gene therapies on the market cost $1 million dollars in the US. The gene therapy developed in Prospera costs $25,000. As to concern about whether such treatments are problematic, we do not share this perspective. We are for advancing science responsibly and we believe that both individuals and society stand to gain from improving the resiliency of the human body through advanced biotechnology.

Q. How does Prospera relate to the local Honduran population?

A. I think it's very important that our projects deliver local benefits and that they're well anchored in local communities. Because when you go to a new place, you're seen as a foreigner, and you're seen as potentially a danger or a threat. The most important thing for Prospera and Ciudad Morazan is to show we're creating jobs; we're creating employment; we're improving people's lives on the ground. Prospera is directly and indirectly employing 1,100 people. More than 2/3 of the people who are working for Prospera are Honduran. It has a lot of local service workers from the island, and it has educated Hondurans from the mainland for whom it's an alternative to going to the United States.

Q. What makes a good Prosperian citizen?

A. People in Prospera are very entrepreneurial. They're opening companies on a small scale. For example, Vehinia, who is the cook in the kitchen at Prospera, she's from the neighboring village and she started an NGO that is now funding a school where children from the local village can go to instead of a school that's 45 minutes away. There's very much a spirit of ‘let's exchange and trade with each other’. Some people might see that as a bit too commercial, but that's something about the culture that people accept and that people see as a good thing.

Q. Five years from now, if everything goes well, what do we see in Prospera?

A. I think Prospera will have at least 10,000 residents and I think Honduras hopefully will have more zones. There could be zones with a thriving industrial sector and sort of a labor-intensive economy and some that are very strong in pharmaceuticals, there could also be other zones for synthetic biology, and other zones focused on agriculture. The zones of Prospera, Ciudad Morazan and Orchidea are already showing the results we want to see, the results that we will eventually be measured by, and I'm tremendously excited about Honduras.