A vaccine for Lyme disease could be coming. But will patients accept it?

Hiking is one of Marci Flory's favorite activities, but her chronic Lyme disease sometimes renders her unable to walk. Biotech companies Pfizer and Valneva are testing a vaccine for Lyme disease in a Phase III clinical trial.

For more than two decades, Marci Flory, a 40-year-old emergency room nurse from Lawrence, Kan., has battled the recurring symptoms of chronic Lyme disease, an illness which she believes began after being bitten by a tick during her teenage years.

Over the years, Flory has been plagued by an array of mysterious ailments, ranging from fatigue to crippling pain in her eyes, joints and neck, and even postural tachycardia syndrome or PoTS, an abnormal increase in heart rate after sitting up or standing. Ten years ago, she began to experience the onset of neurological symptoms which ranged from brain fog to sudden headaches, and strange episodes of leg weakness which would leave her unable to walk.

“Initially doctors thought I had ALS, or less likely, multiple sclerosis,” she says. “But after repeated MRI scans for a year, they concluded I had a rare neurological condition called acute transverse myelitis.”

But Flory was not convinced. After ordering a variety of private blood tests, she discovered she was infected with a range of bacteria in the genus Borrelia that live in the guts of ticks, the infectious agents responsible for Lyme disease.

“It made sense,” she says. “Looking back, I was bitten in high school and misdiagnosed with mononucleosis. This was probably the start, and my immune system kept it under wraps for a while. The Lyme bacteria can burrow into every tissue in the body, go into cyst form and become dormant before reactivating.”

The reason why cases of Lyme disease are increasing is down to changing weather patterns, triggered by climate change, meaning that ticks are now found across a much wider geographic range than ever before.

When these species of bacteria are transmitted to humans, they can attack the nervous system, joints and even internal organs which can lead to serious health complications such as arthritis, meningitis and even heart failure. While Lyme disease can sometimes be successfully treated with antibiotics if spotted early on, not everyone responds to these drugs, and for patients who have developed chronic symptoms, there is no known cure. Flory says she knows of fellow Lyme disease patients who have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars seeking treatments.

Concerningly, statistics show that Lyme and other tick-borne diseases are on the rise. Recently released estimates based on health insurance records suggest that at least 476,000 Americans are diagnosed with Lyme disease every year, and many experts believe the true figure is far higher.

The reason why the numbers are growing is down to changing weather patterns, triggered by climate change, meaning that ticks are now found across a much wider geographic range than ever before. Health insurance data shows that cases of Lyme disease have increased fourfold in rural parts of the U.S. over the last 15 years, and 65 percent in urban regions.

As a result, many scientists who have studied Lyme disease feel that it is paramount to bring some form of protective vaccine to market which can be offered to people living in the most at-risk areas.

“Even the increased awareness for Lyme disease has not stopped the cases,” says Eva Sapi, professor of cellular and molecular biology at the University of New Haven. “Some of these patients are looking for answers for years, running from one doctor to another, so that is obviously a very big cost for our society at so many levels.”

Emerging vaccines – and backlash

But with the rising case numbers, interest has grown among the pharmaceutical industry and research communities. Vienna-based biotech Valneva have partnered with Pfizer to take their vaccine – a seasonal jab which offers protection against the six most common strains of Lyme disease in the northern hemisphere – into a Phase III clinical trial which began in August. Involving 6,000 participants in a number of U.S. states and northern Europe where Lyme disease is endemic, it could lead to a licensed vaccine by 2025, if it proves successful.

“For many years Lyme was considered a small market vaccine,” explains Monica E. Embers, assistant professor of parasitology at Tulane University in New Orleans. “Now we know that this is a much bigger problem, Pfizer has stepped up to invest in preventing this disease and other pharmaceutical companies may as well.”

Despite innovations, patient communities and their representatives remain ambivalent about the idea of a vaccine. Some of this skepticism dates back to the failed LYMErix vaccine which was developed in the late 1990s before being withdrawn from the market.

At the same time, scientists at Yale University are developing a messenger RNA vaccine which aims to train the immune system to respond to tick bites by exposing it to 19 proteins found in tick saliva. Whereas the Valneva vaccine targets the bacteria within ticks, the Yale vaccine attempts to provoke an instant and aggressive immune response at the site of the bite. This causes the tick to fall off and limits the potential for transmitting dangerous infections.

But despite these innovations, patient communities and their representatives remain ambivalent about the idea of a vaccine. Some of this skepticism dates back to the failed LYMErix vaccine which was developed in the late 1990s before being withdrawn from the market in 2002 after concerns were raised that it might induce autoimmune reactions in humans.

While this theory was ultimately disproved, the lingering stigma attached to LYMErix meant that most vaccine manufacturers chose to stay away from the disease for many years, something which Gregory Poland, head of the Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group in Minnesota, describes as a tragedy.

“Since 2002, we have not had a human Lyme vaccine in the U.S. despite the increasing number of cases,” says Poland. “Pretty much everyone in the field thinks they’re ten times higher than the official numbers, so you’re probably talking at least 400,000 each year. It’s an incredible burden but because of concerns about anti-vax protestors, until very recently, no manufacturer has wanted to touch this.”

Such was the backlash surrounding the failed LYMErix program that scientists have even explored the most creative of workarounds for protecting people in tick-populated regions, without needing to actually vaccinate them. One research program at the University of Tennessee came up with the idea of leaving food pellets containing a vaccine in woodland areas with the idea that rodents would eat the pellets, and the vaccine would then kill Borrelia bacteria within any ticks which subsequently fed on the animals.

Even the Pfizer-Valneva vaccine has been cautiously designed to try and allay any lingering concerns, two decades after LYMErix. “The concept is the same as the original LYMErix vaccine, but it has been made safer by removing regions that had the potential to induce autoimmunity,” says Embers. “There will always be individuals who oppose vaccines, Lyme or otherwise, but it will be a tremendous boost to public health to have the option.”

Vaccine alternatives

Researchers are also considering alternative immunization approaches in case sufficiently large numbers of people choose to reject any Lyme vaccine which gets approved. Researchers at UMass Chan Medical School have developed an artificially generated antibody, administered via an annual injection, which is capable of killing Borrelia bacteria in the guts of ticks before they can get into the human host.

So far animal studies have shown it to be 100 percent effective, while the scientists have completed a Phase I trial in which they tested it for safety on 48 volunteers in Nebraska. Because this approach provides the antibody directly, rather than triggering the human immune system to produce the antibody like a vaccine would, Embers predicts that it could be a viable alternative for the vaccine hesitant as well as providing an option for immunocompromised individuals who cannot produce enough of their own antibodies.

At the same time, many patient groups still raise concerns over the fact that numerous diagnostic tests for Lyme disease have been reported to have a poor accuracy. Without this, they argue that it is difficult to prove whether vaccines or any other form of immunization actually work. “If the disease is not understood enough to create a more accurate test and a universally accepted treatment protocol, particularly for those who weren’t treated promptly, how can we be sure about the efficacy of a vaccine?” says Natasha Metcalf, co-founder of the organization Lyme Disease UK.

Flory points out that there are so many different types of Borrelia bacteria which cause Lyme disease, that the immunizations being developed may only stop a proportion of cases. In addition, she says that chronic Lyme patients often report a whole myriad of co-infections which remain poorly understood and are likely to also be involved in the disease process.

Marci Flory undergoes an infusion in an attempt to treat her Lyme disease symptoms.

Marci Flory

“I would love to see an effective Lyme vaccine but I have my reservations,” she says. “I am infected with four types of Borrelia bacteria, plus many co-infections – Babesia, Bartonella, Erlichiosis, Rickettsia, and Mycoplasma – all from a single Douglas County Kansas tick bite. Lyme never travels alone and the vaccine won’t protect against all the many strains of Borrelia and co-infections.”

Valneva CEO Thomas Lingelbach admits that the Pfizer-Valneva vaccine is not perfect, but predicts that it will still have significant impact if approved.

“We expect the vaccine to have 75 percent plus efficacy,” he says. “There is this legacy around the old Lyme vaccines, but the world is very, very different today. The number of clinical manifestations known to be caused by infection with Lyme Borreliosis has significantly increased, and the understanding around severity has certainly increased.”

Embers agrees that while it will still be important for doctors to monitor for other tick-borne infections which are not necessarily covered by the vaccine, having any clinically approved jab would still represent a major step forward in the fight against the disease.

“I think that any vaccine must be properly vetted, and these companies are performing extensive clinical trials to do just that,” she says. “Lyme is the most common tick-borne disease in the U.S. so the public health impact could be significant. However, clinicians and the general public must remain aware of all of the other tick-borne diseases such as Babesia and Anaplasma, and continue to screen for those when a tick bite is suspected.”

The U.S. must fund more biotech innovation – or other countries will catch up faster than you think

In the coming years, U.S. market share in biotech will decline unless the federal government makes investments to improve the quality and quantity of U.S. research, writes the author.

The U.S. has approximately 58 percent of the market share in the biotech sector, followed by China with 11 percent. However, this market share is the result of several years of previous research and development (R&D) – it is a present picture of what happened in the past. In the future, this market share will decline unless the federal government makes investments to improve the quality and quantity of U.S. research in biotech.

The effectiveness of current R&D can be evaluated in a variety of ways such as monies invested and the number of patents filed. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the U.S. spends approximately 2.7 percent of GDP on R&D ($476,459.0M), whereas China spends 2 percent ($346,266.3M). However, investment levels do not necessarily translate into goods that end up contributing to innovation.

Patents are a better indication of innovation. The biotech industry relies on patents to protect their investments, making patenting a key tool in the process of translating scientific discoveries that can ultimately benefit patients. In 2020, China filed 1,497,159 patents, a 6.9 percent increase in growth rate. In contrast, the U.S. filed 597,172, a 3.9 percent decline. When it comes to patents filed, China has approximately 45 percent of the world share compared to 18 percent for the U.S.

So how did we get here? The nature of science in academia allows scientists to specialize by dedicating several years to advance discovery research and develop new inventions that can then be licensed by biotech companies. This makes academic science critical to innovation in the U.S. and abroad.

Academic scientists rely on government and foundation grants to pay for R&D, which includes salaries for faculty, investigators and trainees, as well as monies for infrastructure, support personnel and research supplies. Of particular interest to academic scientists to cover these costs is government support such as Research Project Grants, also known as R01 grants, the oldest grant mechanism from the National Institutes of Health. Unfortunately, this funding mechanism is extremely competitive, as applications have a success rate of only about 20 percent. To maximize the chances of getting funded, investigators tend to limit the innovation of their applications, since a project that seems overambitious is discouraged by grant reviewers.

Considering the difficulty in obtaining funding, the limited number of opportunities for scientists to become independent investigators capable of leading their own scientific projects, and the salaries available to pay for scientists with a doctoral degree, it is not surprising that the U.S. is progressively losing its workforce for innovation.

This approach affects the future success of the R&D enterprise in the U.S. Pursuing less innovative work tends to produce scientific results that are more obvious than groundbreaking, and when a discovery is obvious, it cannot be patented, resulting in fewer inventions that go on to benefit patients. Even though there are governmental funding options available for scientists in academia focused on more groundbreaking and translational projects, those options are less coveted by academic scientists who are trying to obtain tenure and long-term funding to cover salaries and other associated laboratory expenses. Therefore, since only a small percent of projects gets funded, the likelihood of scientists interested in pursuing academic science or even research in general keeps declining over time.

Efforts to raise the number of individuals who pursue a scientific education are paying off. However, the number of job openings for those trainees to carry out independent scientific research once they graduate has proved harder to increase. These limitations are not just in the number of faculty openings to pursue academic science, which are in part related to grant funding, but also the low salary available to pay those scientists after they obtain their doctoral degree, which ranges from $53,000 to $65,000, depending on years of experience.

Thus, considering the difficulty in obtaining funding, the limited number of opportunities for scientists to become independent investigators capable of leading their own scientific projects, and the salaries available to pay for scientists with a doctoral degree, it is not surprising that the U.S. is progressively losing its workforce for innovation, which results in fewer patents filed.

Perhaps instead of encouraging scientists to propose less innovative projects in order to increase their chances of getting grants, the U.S. government should give serious consideration to funding investigators for their potential for success -- or the success they have already achieved in contributing to the advancement of science. Such a funding approach should be tiered depending on career stage or years of experience, considering that 42 years old is the median age at which the first R01 is obtained. This suggests that after finishing their training, scientists spend 10 years before they establish themselves as independent academic investigators capable of having the appropriate funds to train the next generation of scientists who will help the U.S. maintain or even expand its market share in the biotech industry for years to come. Patenting should be given more weight as part of the academic endeavor for promotion purposes, or governmental investment in research funding should be increased to support more than just 20 percent of projects.

Remaining at the forefront of biotech innovation will give us the opportunity to not just generate more jobs, but it will also allow us to attract the brightest scientists from all over the world. This talented workforce will go on to train future U.S. scientists and will improve our standard of living by giving us the opportunity to produce the next generation of therapies intended to improve human health.

This problem cannot rely on just one solution, but what is certain is that unless there are more creative changes in funding approaches for scientists in academia, eventually we may be saying “remember when the U.S. was at the forefront of biotech innovation?”

New gene therapy helps patients with rare disease. One mother wouldn't have it any other way.

A biotech in Cambridge, Mass., is targeting a rare disease called cystinosis with gene therapy. It's been effective for five patients in a clinical trial that's still underway.

Three years ago, Jordan Janz of Consort, Alberta, knew his gene therapy treatment for cystinosis was working when his hair started to darken. Pigmentation or melanin production is just one part of the body damaged by cystinosis.

“When you have cystinosis, you’re either a redhead or a blonde, and you are very pale,” attests Janz, 23, who was diagnosed with the disease just eight months after he was born. “After I got my new stem cells, my hair came back dark, dirty blonde, then it lightened a little bit, but before it was white blonde, almost bleach blonde.”

According to Cystinosis United, about 500 to 600 people have the rare genetic disease in the U.S.; an estimated 20 new cases are diagnosed each year.

Located in Cambridge, Mass., AVROBIO is a gene therapy company that targets cystinosis and other lysosomal storage disorders, in which toxic materials build up in the cells. Janz is one of five patients in AVROBIO’s ongoing Phase 1/2 clinical trial of a gene therapy for cystinosis called AVR-RD-04.

Recently, AVROBIO compiled positive clinical data from this first and only gene therapy trial for the disease. The data show the potential of the therapy to genetically modify the patients’ own hematopoietic stem cells—a certain type of cell that’s capable of developing into all different types of blood cells—to express the functional protein they are deficient in. It stabilizes or reduces the impact of cystinosis on multiple tissues with a single dose.

Medical researchers have found that more than 80 different mutations to a gene called CTNS are responsible for causing cystinosis. The most common mutation results in a deficiency of the protein cystinosin. That protein functions as a transporter that regulates a lot metabolic processes in the cells.

“One of the first things we see in patients clinically is an accumulation of a particular amino acid called cystine, which grows toxic cystine crystals in the cells that cause serious complications,” explains Essra Rihda, chief medical officer for AVROBIO. “That happens in the cells across the tissues and organs of the body, so the disease affects many parts of the body.”

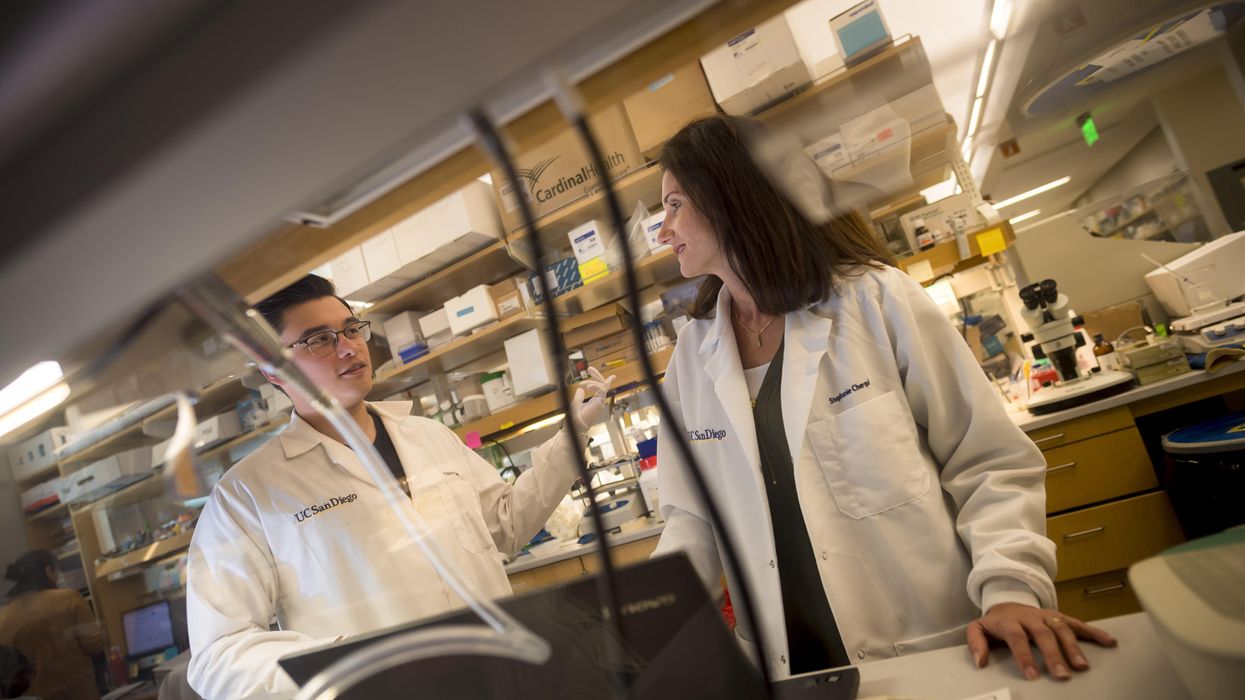

Jordan Janz, 23, meets Stephanie Cherqui, the principal investigator of his gene therapy trial, before the trial started in 2019.

Jordan Janz

According to Rihda, although cystinosis can occur in kids and adults, the most severe form of the disease affects infants and makes up about 95 percent of overall cases. Children typically appear healthy at birth, but around six to 18 months, they start to present for medical attention with failure to thrive.

Additionally, infants with cystinosis often urinate frequently, a sign of polyuria, and they are thirsty all the time, since the disease usually starts in the kidneys. Many develop chronic kidney disease that ultimately progresses to the point where the kidney no longer supports the body’s needs. At that stage, dialysis is required and then a transplant. From there the disease spreads to many other organs, including the eyes, muscles, heart, nervous system, etc.

“The gene for cystinosis is expressed in every single tissue we have, and the accumulation of this toxic buildup alters all of the organs of the patient, so little by little all of the organs start to fail,” says Stephanie Cherqui, principal investigator of Cherqui Lab, which is part of UC San Diego’s Department of Pediatrics.

Since the 1950s, a drug called cysteamine showed some therapeutic effect on cystinosis. It was approved by the FDA in 1994 to prevent damage that may be caused by the buildup of cystine crystals in organs. Prior to FDA approval, Cherqui says, children were dying of the disease before they were ten-years-old or after a kidney transplant. By taking oral cysteamine, they can live from 20 to 50 years longer. But it’s a challenging drug because it has to be taken every 6 or 12 hours, and there are serious gastric side effects such as nausea and diarrhea.

“With all of the complications they develop, the typical patient takes 40 to 60 pills a day around the clock,” Cherqui says. “They literally have a suitcase of medications they have to carry everywhere, and all of those medications don’t stop the progression of the disease, and they still die from it.”

Cherqui has been a proponent of gene therapy to treat children’s disorders since studying cystinosis while earning her doctorate in 2002. Today, her lab focuses on developing stem cell and gene therapy strategies for degenerative, hereditary disorders such as cystinosis that affect multiple systems of the body. “Because cystinosis expresses in every tissue in the body, I decided to use the blood-forming stem cells that we have in our bone marrow,” she explains. “These cells can migrate to anywhere in the body where the person has an injury from the disease.”

AVROBIO’s hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy approach collects stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow. They then genetically modify the stem cells to give the patient a copy of the healthy CTNS gene, which the person either doesn’t have or it’s defective.

The patient first undergoes apheresis, a medical procedure in which their blood is passed through an apparatus that separates out the diseased stem cells, and a process called conditioning is used to help eliminate the damaged cells so they can be replaced by the infusion of the patient’s genetically modified stem cells. Once they become engrafted into the patient’s bone marrow, they reproduce into a lot of daughter cells, and all of those daughter cells contain the CTNS gene. Those cells are able to express the healthy, functional, active protein throughout the body to correct the metabolic problem caused by cystinosis.

“What we’re seeing in the adult patients who have been dosed to date is the consistent and sustained engraftment of our genetically modified cells, 17 to 27 months post-gene therapy, so that’s very encouraging and positive,” says Rihda, the chief medical officer at AVROBIO.

When Janz was 11-years-old, his mother got him enrolled in the trial of a new form of cysteamine that would only need to be taken every 12 hours instead of every six. Two years later, she made sure he was the first person on the list for Cherqui’s current stem cell gene therapy trial.

AVROBIO researchers have also confirmed stabilization or improvement in motor coordination and visual perception in the trial participants, suggesting a potential impact on the neuropathology of the disease. Data from five dosed patients show strong safety and tolerability as well as reduced accumulation of cystine crystals in cells across multiple tissues in the first three patients. None of the five patients need to take oral cysteamine.

Janz’s mother, Barb Kulyk, whom he credits with always making him take his medications and keeping him hydrated, had been following Cherqui’s research since his early childhood. When Janz was 11-years-old, she got him enrolled in the trial of a new form of cysteamine that would only need to be taken every 12 hours instead of every six. When he was 17, the FDA approved that drug. Two years later, his mother made sure he was the first person on the list for Cherqui’s current stem cell gene therapy trial. He received his new stem cells on October 7th, 2019, went home in January 2020, and returned to working full time in February.

Jordan Janz, pictured here with his girlfriend, has a new lease on life, plus a new hair color.

Jordan Janz

He notes that his energy level is significantly better, and his mother has noticed much improvement in him and his daily functioning: He rarely vomits or gets nauseous in the morning, and he has more color in his face as well as his hair. Although he could finish his participation at any time, he recently decided to continue in the clinical trial.

Before the trial, Janz was taking 56 pills daily. He is completely off all of those medications and only takes pills to keep his kidneys working. Because of the damage caused by cystinosis over the course of his life, he’s down to about 20 percent kidney function and will eventually need a transplant.

“Some day, though, thanks to Dr. Cherqui’s team and AVROBIO’s work, when I get a new kidney, cystinosis won’t destroy it,” he concludes.