Scientists experiment with burning iron as a fuel source

Sparklers produce a beautiful display of light and heat by burning metal dust, which contains iron. The recent work of Canadian and Dutch researchers suggests we can use iron as a cheap, carbon-free fuel.

Story by Freethink

Try burning an iron metal ingot and you’ll have to wait a long time — but grind it into a powder and it will readily burst into flames. That’s how sparklers work: metal dust burning in a beautiful display of light and heat. But could we burn iron for more than fun? Could this simple material become a cheap, clean, carbon-free fuel?

In new experiments — conducted on rockets, in microgravity — Canadian and Dutch researchers are looking at ways of boosting the efficiency of burning iron, with a view to turning this abundant material — the fourth most common in the Earth’s crust, about about 5% of its mass — into an alternative energy source.

Iron as a fuel

Iron is abundantly available and cheap. More importantly, the byproduct of burning iron is rust (iron oxide), a solid material that is easy to collect and recycle. Neither burning iron nor converting its oxide back produces any carbon in the process.

Iron oxide is potentially renewable by reacting with electricity or hydrogen to become iron again.

Iron has a high energy density: it requires almost the same volume as gasoline to produce the same amount of energy. However, iron has poor specific energy: it’s a lot heavier than gas to produce the same amount of energy. (Think of picking up a jug of gasoline, and then imagine trying to pick up a similar sized chunk of iron.) Therefore, its weight is prohibitive for many applications. Burning iron to run a car isn’t very practical if the iron fuel weighs as much as the car itself.

In its powdered form, however, iron offers more promise as a high-density energy carrier or storage system. Iron-burning furnaces could provide direct heat for industry, home heating, or to generate electricity.

Plus, iron oxide is potentially renewable by reacting with electricity or hydrogen to become iron again (as long as you’ve got a source of clean electricity or green hydrogen). When there’s excess electricity available from renewables like solar and wind, for example, rust could be converted back into iron powder, and then burned on demand to release that energy again.

However, these methods of recycling rust are very energy intensive and inefficient, currently, so improvements to the efficiency of burning iron itself may be crucial to making such a circular system viable.

The science of discrete burning

Powdered particles have a high surface area to volume ratio, which means it is easier to ignite them. This is true for metals as well.

Under the right circumstances, powdered iron can burn in a manner known as discrete burning. In its most ideal form, the flame completely consumes one particle before the heat radiating from it combusts other particles in its vicinity. By studying this process, researchers can better understand and model how iron combusts, allowing them to design better iron-burning furnaces.

Discrete burning is difficult to achieve on Earth. Perfect discrete burning requires a specific particle density and oxygen concentration. When the particles are too close and compacted, the fire jumps to neighboring particles before fully consuming a particle, resulting in a more chaotic and less controlled burn.

Presently, the rate at which powdered iron particles burn or how they release heat in different conditions is poorly understood. This hinders the development of technologies to efficiently utilize iron as a large-scale fuel.

Burning metal in microgravity

In April, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a suborbital “sounding” rocket, carrying three experimental setups. As the rocket traced its parabolic trajectory through the atmosphere, the experiments got a few minutes in free fall, simulating microgravity.

One of the experiments on this mission studied how iron powder burns in the absence of gravity.

In microgravity, particles float in a more uniformly distributed cloud. This allows researchers to model the flow of iron particles and how a flame propagates through a cloud of iron particles in different oxygen concentrations.

Existing fossil fuel power plants could potentially be retrofitted to run on iron fuel.

Insights into how flames propagate through iron powder under different conditions could help design much more efficient iron-burning furnaces.

Clean and carbon-free energy on Earth

Various businesses are looking at ways to incorporate iron fuels into their processes. In particular, it could serve as a cleaner way to supply industrial heat by burning iron to heat water.

For example, Dutch brewery Swinkels Family Brewers, in collaboration with the Eindhoven University of Technology, switched to iron fuel as the heat source to power its brewing process, accounting for 15 million glasses of beer annually. Dutch startup RIFT is running proof-of-concept iron fuel power plants in Helmond and Arnhem.

As researchers continue to improve the efficiency of burning iron, its applicability will extend to other use cases as well. But is the infrastructure in place for this transition?

Often, the transition to new energy sources is slowed by the need to create new infrastructure to utilize them. Fortunately, this isn’t the case with switching from fossil fuels to iron. Since the ideal temperature to burn iron is similar to that for hydrocarbons, existing fossil fuel power plants could potentially be retrofitted to run on iron fuel.

This article originally appeared on Freethink, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Tiny, tough “water bears” may help bring new vaccines and medicines to sub-Saharan Africa

Tardigrades can completely dehydrate and later rehydrate themselves, a survival trick that scientists are harnessing to preserve medicines in hot temperatures.

Microscopic tardigrades, widely considered to be some of the toughest animals on earth, can survive for decades without oxygen or water and are thought to have lived through a crash-landing on the moon. Also known as water bears, they survive by fully dehydrating and later rehydrating themselves – a feat only a few animals can accomplish. Now scientists are harnessing tardigrades’ talents to make medicines that can be dried and stored at ambient temperatures and later rehydrated for use—instead of being kept refrigerated or frozen.

Many biologics—pharmaceutical products made by using living cells or synthesized from biological sources—require refrigeration, which isn’t always available in many remote locales or places with unreliable electricity. These products include mRNA and other vaccines, monoclonal antibodies and immuno-therapies for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions. Cooling is also needed for medicines for blood clotting disorders like hemophilia and for trauma patients.

Formulating biologics to withstand drying and hot temperatures has been the holy grail for pharmaceutical researchers for decades. It’s a hard feat to manage. “Biologic pharmaceuticals are highly efficacious, but many are inherently unstable,” says Thomas Boothby, assistant professor of molecular biology at University of Wyoming. Therefore, during storage and shipping, they must be refrigerated at 2 to 8 degrees Celsius (35 to 46 degrees Fahrenheit). Some must be frozen, typically at -20 degrees Celsius, but sometimes as low -90 degrees Celsius as was the case with the Pfizer Covid vaccine.

For Covid, fewer than 73 percent of the global population received even one dose. The need for refrigerated or frozen handling was partially to blame.

The costly cold chain

The logistics network that ensures those temperature requirements are met from production to administration is called the cold chain. This cold chain network is often unreliable or entirely lacking in remote, rural areas in developing nations that have malfunctioning electrical grids. “Almost all routine vaccines require a cold chain,” says Christopher Fox, senior vice president of formulations at the Access to Advanced Health Institute. But when the power goes out, so does refrigeration, putting refrigerated or frozen medical products at risk. Consequently, the mRNA vaccines developed for Covid-19 and other conditions, as well as more traditional vaccines for cholera, tetanus and other diseases, often can’t be delivered to the most remote parts of the world.

To understand the scope of the challenge, consider this: In the U.S., more than 984 million doses of Covid-19 vaccine have been distributed so far. Each one needed refrigeration that, even in the U.S., proved challenging. Now extrapolate to all vaccines and the entire world. For Covid, fewer than 73 percent of the global population received even one dose. The need for refrigerated or frozen handling was partially to blame.

Globally, the cold chain packaging market is valued at over $15 billion and is expected to exceed $60 billion by 2033.

Adobe Stock

Freeze-drying, also called lyophilization, which is common for many vaccines, isn’t always an option. Many freeze-dried vaccines still need refrigeration, and even medicines approved for storage at ambient temperatures break down in the heat of sub-Saharan Africa. “Even in a freeze-dried state, biologics often will undergo partial rehydration and dehydration, which can be extremely damaging,” Boothby explains.

The cold chain is also very expensive to maintain. The global pharmaceutical cold chain packaging market is valued at more than $15 billion, and is expected to exceed $60 billion by 2033, according to a report by Future Market Insights. This cost is only expected to grow. According to the consulting company Accenture, the number of medicines that require the cold chain are expected to grow by 48 percent, compared to only 21 percent for non-cold-chain therapies.

Tardigrades to the rescue

Tardigrades are only about a millimeter long – with four legs and claws, and they lumber around like bears, thus their nickname – but could provide a big solution. “Tardigrades are unique in the animal kingdom, in that they’re able to survive a vast array of environmental insults,” says Boothby, the Wyoming professor. “They can be dried out, frozen, heated past the boiling point of water and irradiated at levels that are thousands of times more than you or I could survive.” So, his team is gradually unlocking tardigrades’ survival secrets and applying them to biologic pharmaceuticals to make them withstand both extreme heat and desiccation without losing efficacy.

Boothby’s team is focusing on blood clotting factor VIII, which, as the name implies, causes blood to clot. Currently, Boothby is concentrating on the so-called cytoplasmic abundant heat soluble (CAHS) protein family, which is found only in tardigrades, protecting them when they dry out. “We showed we can desiccate a biologic (blood clotting factor VIII, a key clotting component) in the presence of tardigrade proteins,” he says—without losing any of its effectiveness.

The researchers mixed the tardigrade protein with the blood clotting factor and then dried and rehydrated that substance six times without damaging the latter. This suggests that biologics protected with tardigrade proteins can withstand real-world fluctuations in humidity.

Furthermore, Boothby’s team found that when the blood clotting factor was dried and stabilized with tardigrade proteins, it retained its efficacy at temperatures as high as 95 degrees Celsius. That’s over 200 degrees Fahrenheit, much hotter than the 58 degrees Celsius that the World Meteorological Organization lists as the hottest recorded air temperature on earth. In contrast, without the protein, the blood clotting factor degraded significantly. The team published their findings in the journal Nature in March.

Although tardigrades rarely live more than 2.5 years, they have survived in a desiccated state for up to two decades, according to Animal Diversity Web. This suggests that tardigrades’ CAHS protein can protect biologic pharmaceuticals nearly indefinitely without refrigeration or freezing, which makes it significantly easier to deliver them in locations where refrigeration is unreliable or doesn’t exist.

The tricks of the tardigrades

Besides the CAHS proteins, tardigrades rely on a type of sugar called trehalose and some other protectants. So, rather than drying up, their cells solidify into rigid, glass-like structures. As that happens, viscosity between cells increases, thereby slowing their biological functions so much that they all but stop.

Now Boothby is combining CAHS D, one of the proteins in the CAHS family, with trehalose. He found that CAHS D and trehalose each protected proteins through repeated drying and rehydrating cycles. They also work synergistically, which means that together they might stabilize biologics under a variety of dry storage conditions.

“We’re finding the protective effect is not just additive but actually is synergistic,” he says. “We’re keen to see if something like that also holds true with different protein combinations.” If so, combinations could possibly protect against a variety of conditions.

Commercialization outlook

Before any stabilization technology for biologics can be commercialized, it first must be approved by the appropriate regulators. In the U.S., that’s the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Developing a new formulation would require clinical testing and vast numbers of participants. So existing vaccines and biologics likely won’t be re-formulated for dry storage. “Many were developed decades ago,” says Fox. “They‘re not going to be reformulated into thermo-stable vaccines overnight,” if ever, he predicts.

Extending stability outside the cold chain, even for a few days, can have profound health, environmental and economic benefits.

Instead, this technology is most likely to be used for the new products and formulations that are just being created. New and improved vaccines will be the first to benefit. Good candidates include the plethora of mRNA vaccines, as well as biologic pharmaceuticals for neglected diseases that affect parts of the world where reliable cold chain is difficult to maintain, Boothby says. Some examples include new, more effective vaccines for malaria and for pathogenic Escherichia coli, which causes diarrhea.

Tallying up the benefits

Extending stability outside the cold chain, even for a few days, can have profound health, environmental and economic benefits. For instance, MenAfriVac, a meningitis vaccine (without tardigrade proteins) developed for sub-Saharan Africa, can be stored at up to 40 degrees Celsius for four days before administration. “If you have a few days where you don’t need to maintain the cold chain, it’s easier to transport vaccines to remote areas,” Fox says, where refrigeration does not exist or is not reliable.

Better health is an obvious benefit. MenAfriVac reduced suspected meningitis cases by 57 percent in the overall population and more than 99 percent among vaccinated individuals.

Lower healthcare costs are another benefit. One study done in Togo found that the cold chain-related costs increased the per dose vaccine price up to 11-fold. The ability to ship the vaccines using the usual cold chain, but transporting them at ambient temperatures for the final few days cut the cost in half.

There are environmental benefits, too, such as reducing fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Cold chain transports consume 20 percent more fuel than non-cold chain shipping, due to refrigeration equipment, according to the International Trade Administration.

A study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University compared the greenhouse gas emissions of the new, oral Vaxart COVID-19 vaccine (which doesn’t require refrigeration) with four intramuscular vaccines (which require refrigeration or freezing). While the Vaxart vaccine is still in clinical trials, the study found that “up to 82.25 million kilograms of CO2 could be averted by using oral vaccines in the U.S. alone.” That is akin to taking 17,700 vehicles out of service for one year.

Although tardigrades’ protective proteins won’t be a component of biologic pharmaceutics for several years, scientists are proving that this approach is viable. They are hopeful that a day will come when vaccines and biologics can be delivered anywhere in the world without needing refrigerators or freezers en route.

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

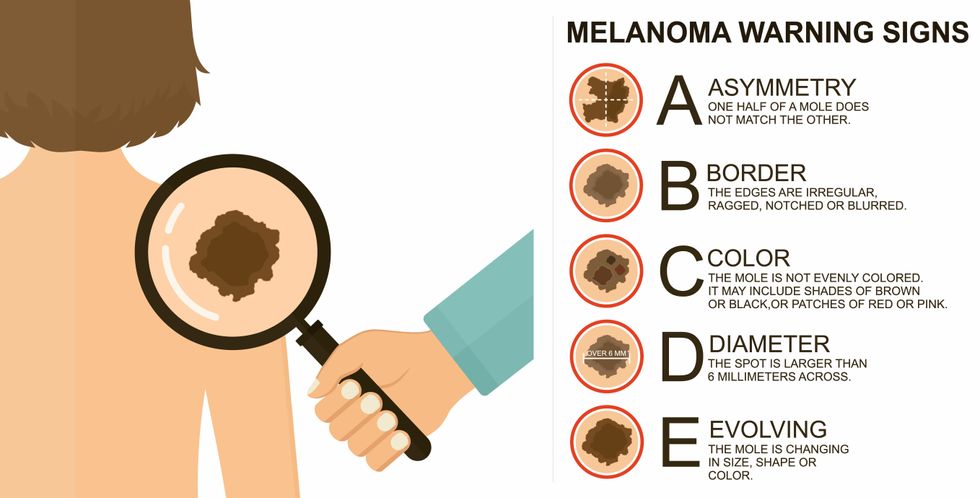

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021