Why Neglected Tropical Diseases Should Matter to Americans

Kissing bugs can carry a parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease.

Daisy Hernández was five years old when one of her favorite aunts was struck with a mysterious illness. Tía Dora had stayed behind in Colombia when Daisy's mother immigrated to Union City, New Jersey. A schoolteacher in her late 20s, she began suffering from fevers and abdominal pain, and her belly grew so big that people thought she was pregnant. Exploratory surgery revealed that her large intestine had swollen to ten times its normal size, and she was fitted with a colostomy bag. Doctors couldn't identify the underlying problem—but whatever it was, they said, it would likely kill her within a year or two.

Tía Dora's sisters in New Jersey—Hernández's mother and two other aunts—weren't about to let that happen. They pooled their savings and flew her to New York City, where a doctor at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center with a penchant for obscure ailments provided a diagnosis: Chagas disease. Transmitted by the bite of triatomine insects, commonly known as kissing bugs, Chagas is endemic in many parts of Latin America. It's caused by the parasite Trypanoma cruzi, which usually settles in the heart, where it feeds on muscle tissue. In some cases, however, it attacks the intestines or esophagus. Tía Dora belonged to that minority.

In 1980, U.S. immigration laws were more forgiving than they are today. Tía Dora was able to have surgery to remove a part of her colon, despite not being a citizen or having a green card. She eventually married a legal resident and began teaching Spanish at an elementary school. Over the next three decades, she earned a graduate degree, built a career, and was widowed. Meanwhile, Chagas continued its slow devastation. "Every couple of years, we were back in the hospital with her," Hernández recalls. "When I was in high school, she started feeling like she couldn't swallow anything. It was the parasite, destroying the muscles of her esophagus."

When Tía Dora died in 2010, at 59, her niece was among the family members at her bedside. By then, Hernández had become a journalist and fiction writer. Researching a short story about Chagas disease, she discovered that it affected an estimated 6 million people in South America, Central America, and Mexico—as well as 300,000 in the United States, most of whom were immigrants from those places. "I was shocked to learn it wasn't rare," she says. "That made me hungry to know more about this disease, and about the families grappling with it."

Hernández's curiosity led her to write The Kissing Bug, a lyrical hybrid of memoir and science reporting that was published in June. It also led her to another revelation: Chagas is not unique. It's among the many maladies that global health experts refer to as neglected tropical diseases—often-disabling illnesses that afflict 1.7 billion people worldwide, while getting notably less attention than the "big three" of HIV/AIDs, malaria, and tuberculosis. NTDs cause fewer deaths than those plagues, but they wreak untold suffering and economic loss.

Shortly before Hernández's book hit the shelves, the World Health Organization released its 2021-2030 roadmap for fighting NTDs. The plan sets targets for controlling, eliminating, or eradicating all the diseases on the WHO's list, through measures ranging from developing vaccines to improving healthcare infrastructure, sanitation, and access to clean water. Experts agree that for the campaign to succeed, leadership from wealthy nations—particularly the United States—is essential. But given the inward turn of many such countries in recent years (evidenced in movements ranging from America First to Brexit), and the continuing urgency of the COVID-19 crisis, public support is far from guaranteed.

As Hernández writes: "It is easier to forget a disease that cannot be seen." NTDs primarily affect residents of distant lands. They kill only 80,000 people a year, down from 204,000 in 1990. So why should Americans to bother to look?

Breaking the circle of poverty and disease

The World Health Organization counts 20 diseases as NTDs. Along with Chagas, they include dengue and chikungunya, which cause high fevers and agonizing pain; elephantiasis, which deforms victims' limbs and genitals; onchocerciasis, which causes blindness; schistosomiasis, which can damage the heart, lungs, brain, and genitourinary system; helminths such as roundworm and whipworm, which cause anemia, stunted growth, and cognitive disabilities; and a dozen more. Such ailments often co-occur in the same patient, exacerbating each other's effects and those of illnesses such as malaria.

NTDs may be spread by insects, animals, soil, or tainted water; they may be parasitic, bacterial, viral, or—in the case of snakebite envenoming—non-infectious. What they have in common is their longtime neglect by public health agencies and philanthropies. In part, this reflects their typically low mortality rates. But the biggest factor is undoubtedly their disempowered patient populations.

"These diseases occur in the setting of poverty, and they cause poverty, because of their chronic and debilitating effects," observes Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor University and co-director of the Texas Children's Hospital for Vaccine Development. And historically, the everyday miseries of impoverished people have seldom been a priority for those who set the global health agenda.

That began to change about 20 years ago, when Hotez and others developed the conceptual framework for NTDs and early proposals for combating them. The WHO released its first roadmap in 2012, targeting 17 NTDs for control, elimination, or eradication by 2020. (Rabies, snakebite, and dengue were added later.) Since then, the number of people at risk for NTDs has fallen by 600 million, and 42 countries have eliminated at least one such disease. Cases of dracunculiasis—known as Guinea worm disease, for the parasite that creates painful blisters in a patient's skin—have dropped from the millions to just 27 in 2020.

Yet the battle is not over, and the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted prevention and treatment programs around the globe.

A new direction — and longstanding obstacles

The WHO's new roadmap sets even more ambitious goals for 2030. Among them: reducing by 90 percent the number of people requiring treatment for NTDs; eliminating at least one NTD in another 100 countries; and fully eradicating dracunculiasis and yaws, a disfiguring skin infection.

The plan also places an increased focus on "country ownership," relying on nations with high incidence of NTDs to design their own plans based on local expertise. "I was so excited to see that," says Kristina Talbert-Slagle, director of the Yale College Global Health Studies program. "No one is a better expert on how to address these situations than the people who deal with it day by day."

Another fresh approach is what the roadmap calls "cross-cutting" targets. "One of the really cool things about the plan is how much it emphasizes coordination among different sectors of the health system," says Claire Standley, a faculty member at Georgetown University's Center for Global Health Science and Security. "For example, it explicitly takes into account the zoonotic nature of many neglected tropical diseases—the fact that we have to think about animal health as well as human health when we tackle NTDs."

Whether this grand vision can be realized, however, will depend largely on funding—and that, in turn, is a question of political will in the countries most able to provide it. On the upside, the U.S. has ended its Trump-era feud with the WHO. "One thing that's been really encouraging," says Standley, "has been the strong commitment toward global cooperation from the current administration." Even under the previous president, the U.S. remained the single largest contributor to the global health kitty, spending over $100 million annually on NTDs—six times the figure in 2006, when such financing started.

On the downside, America's outlay has remained flat for several years, and the Biden administration has so far not moved to increase it. A "back-of-the-envelope calculation," says Hotez, suggests that the current level of aid could buy medications for the most common NTDs for about 200 million people a year. But the number of people who need treatment, he notes, is at least 750 million.

Up to now, the United Kingdom—long the world's second-most generous health aid donor—has taken up a large portion of the slack. But the UK last month announced deep cuts in its portfolio, eliminating 102 previously supported countries and leaving only 34. "That really concerns me," Hotez says.

The struggle for funds, he notes, is always harder for projects involving NTDs than for those aimed at higher-profile diseases. His lab, which he co-directs with microbiologist Maria Elena Bottazzi, started developing a COVID-19 vaccine soon after the pandemic struck, for example, and is now in Phase 3 trials. The team has been working on vaccines for Chagas, hookworm, and schistosomiasis for much longer, but trials for those potential game-changers lag behind. "We struggle to get the level of resources needed to move quickly," Hotez explains.

Two million reasons to care

One way to prompt a government to open its pocketbook is for voters to clamor for action. A longtime challenge with NTDs, however, has been getting people outside the hardest-hit countries to pay attention.

The reasons to care, global health experts argue, go beyond compassion. "When we have high NTD burden," says Talbert-Slagle, "it can prevent economic growth, prevent innovation, lead to more political instability." That, in turn, can lead to wars and mass migration, affecting economic and political events far beyond an affected country's borders.

Like Hernández's aunt Dora, many people driven out of NTD-wracked regions wind up living elsewhere. And that points to another reason to care about these diseases: Some of your neighbors might have them. In the U.S., up to 14 million people suffer from neglected parasitic infections—including 70,000 with Chagas in California alone.

When Hernández was researching The Kissing Bug, she worried that such statistics would provide ammunition to racists and xenophobes who claim that immigrants "bring disease" or exploit overburdened healthcare systems. (This may help explain some of the stigma around NTDs, which led Tía Dora to hide her condition from most people outside her family.) But as the book makes clear, these infections know no borders; they flourish wherever large numbers of people lack access to resources that most residents of rich countries take for granted.

Indeed, far from gaming U.S. healthcare systems, millions of low-income immigrants can't access them—or must wait until they're sick enough to go to an emergency room. Since Congress changed the rules in 1996, green card holders have to wait five years before they can enroll in Medicaid. Undocumented immigrants can never qualify.

Closing the great divide

Hernández uses a phrase borrowed from global health crusader Paul Farmer to describe this access gap: "the great epi divide." On one side, she explains, "people will die from cancer, from diabetes, from chronic illnesses later in life. On the other side of the epidemiological divide, people are dying because they can't get to the doctor, or they can't get medication. They don't have a hospital anywhere near them. When I read Dr. Farmer's work, I realized how much that applied to neglected diseases as well."

When it comes to Chagas disease, she says, the epi divide is embodied in the lack of a federal mandate for prenatal or newborn screening. Each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, up to 300 babies in the U.S. are born with Chagas, which can be passed from the mother in utero. The disease can be cured with medication if treated in infancy. (It can also be cured in adults in the acute stage, but is seldom detected in time.) Yet the CDC does not require screening for Chagas—even though newborns are tested for 15 diseases that are less common. According to one study, it would be 10 times cheaper to screen and treat babies and their mothers than to cover the costs related to the illness in later years. Few states make the effort.

The gap that enables NTDs to persist, Hernández argues, is the same one that has led to COVID-19 death rates in Black and Latinx communities that are double those elsewhere in America. To close it, she suggests, caring is not enough.

"When I was working on my book," she says, "I thought about HIV in the '80s, when it had so much stigma that no one wanted to talk about it. Then activists stepped up and changed the conversation. I thought a lot about breast cancer, which was stigmatized for years, until people stepped forward and started speaking out. I thought about Lyme disease. And it wasn't only patients—it was also allies, right? The same thing needs to happen with neglected diseases around the world. Allies need to step up and make demands on policymakers. We need to make some noise."

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

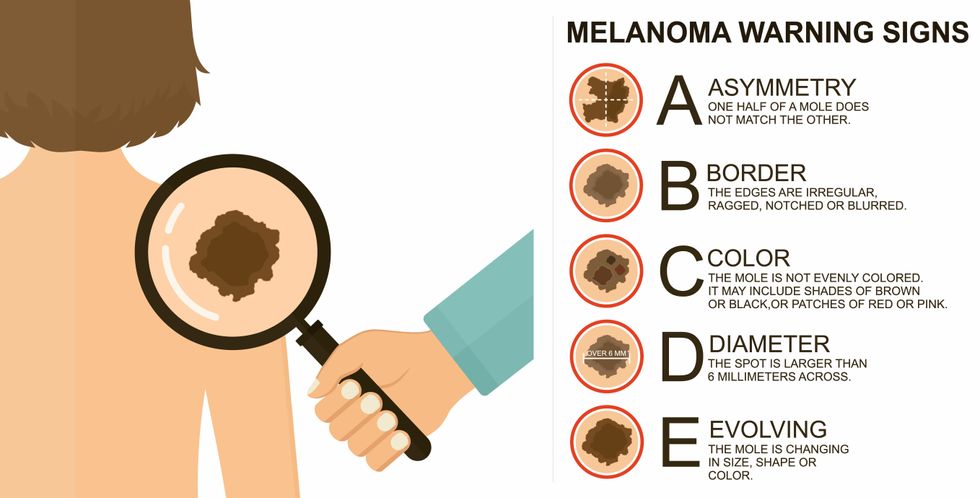

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.