New Options Are Emerging in the Search for Better Birth Control

A decade ago, Elizabeth Summers' options for birth control suddenly narrowed. Doctors diagnosed her with Factor V Leiden, a rare genetic disorder, after discovering blood clots in her lungs. The condition increases the risk of clotting, so physicians told Summers to stay away from the pill and other hormone-laden contraceptives. "Modern medicine has generally failed to provide me with an effective and convenient option," she says.

But new birth control options are emerging for women like Summers. These alternatives promise to provide more choices to women who can't ingest hormones or don't want to suffer their unpleasant side effects.

These new products have their own pros and cons. Still, doctors are welcoming new contraceptives following a long drought in innovation. "It's been a long time since we've had something new in the world of contraception," says Heather Irobunda, an obstetrician and gynecologist at NYC Health and Hospitals.

On social media, Irobunda often fields questions about one of these new options, a lubricating gel called Phexxi. San Diego-based Evofem, the company behind Phexxi, has been advertising the product on Hulu and Instagram after the gel was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2020. The company's trendy ads target women who feel like condoms diminish the mood, but who also don't want to mess with an IUD or hormones.

Here's how it works: Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex. The gel regulates vaginal pH — essentially, the acidity levels — in a range that's inhospitable to sperm. It sounds a lot like spermicide, which is also placed in the vagina prior to sex to prevent pregnancy. But spermicide can damage the vagina's cell walls, which can increase the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

"Not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option."

Phexxi isn't without side effects either. The most common one is vaginal burning, according to a late-stage trial. It's also possible to develop a urinary tract infection while using the product. That same study found that during typical use, Phexxi is about 86 percent effective at preventing pregnancy. The efficacy rate is comparable to condoms but lower than birth control pills (91 percent) and significantly lower than an IUD (99 percent).

Phexxi – which comes in a pack of 12 – represents a tiny but growing part of the birth control market. Pharmacies dispensed more than 14,800 packs from April through June this year, a 65 percent increase over the previous quarter, according to data from Evofem.

"We've been able to demonstrate that not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option," says Saundra Pelletier, Evofem's CEO.

Beyond contraception, the company is carrying out late-stage tests to gauge Phexxi's effectiveness at preventing the sexually transmitted infections chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex.

Phexxi

A New Pill

The first birth control pill arrived in 1960, combining the hormones estrogen and progestin to stop sperm from joining with an egg, giving women control over their fertility. Subsequent formulations sought to ease side effects, by way of lower amounts of estrogen. But some women still experience headaches and nausea – or more serious complications like blood clots. On social media, women recently noted that birth control pills are much more likely to cause blood clots than Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine that was briefly paused to evaluate the risk of clots in women under age 50. What will it take, they wondered, for safer birth control?

Mithra Pharmaceuticals of Belgium sought to create a gentler pill. In April, the FDA approved Mithra's Nextstellis, which includes a naturally occurring estrogen, the first new estrogen in the U.S. in 50 years. Nextstellis selectively acts on tissues lining the uterus, while other birth control pills have a broader target.

A Phase 3 trial showed a 98 percent efficacy rate. Andrew London, an obstetrician and gynecologist, who practices at several Maryland hospitals, says the results are in line with some other birth control pills. But, he added, early studies indicate that Nextstellis has a lower risk of blood clotting, along with other potential benefits, which additional clinical testing must confirm.

"It's not going to be worse than any other pill. We're hoping it's going to be significantly better," says London.

The estrogen in Nexstellis, called estetrol, was skipped over by the pharmaceutical industry after its discovery in the 1960s. Estetrol circulates between the mother and fetus during pregnancy. Decades later, researchers took a new look, after figuring out how to synthesize estetrol in a lab, as well as produce estetrol from plants.

"That allowed us to really start to investigate the properties and do all this stuff you have to do for any new drug," says Michele Gordon, vice president of marketing in women's health at Mayne Pharma, which licensed Nextstellis.

Bonnie Douglas, who followed the development of Nextstellis as part of a search for better birth control, recently switched to the product. "So far, it's much more tolerable," says Douglas. Previously, the Midwesterner was so desperate to find a contraceptive with fewer side effects that she turned to an online pharmacy to obtain a different birth control pill that had been approved in Canada but not in the U.S.

Contraceptive Access

Even if a contraceptive lands FDA approval, access poses a barrier. Getting insurers to cover new contraceptives can be difficult. For the uninsured, state and federal programs can help, and companies should keep prices in a reasonable range, while offering assistance programs. So says Kelly Blanchard, president of the nonprofit Ibis Reproductive Health. "For innovation to have impact, you want to reach as many folks as possible," she says.

In addition, companies developing new contraceptives have struggled to attract venture capital. That's changing, though.

In 2015, Sabrina Johnson founded DARÉ Bioscience around the idea of women's health. She estimated the company would be fully funded in six months, based on her track record in biotech and the demand for novel products.

But it's been difficult to get male investors interested in backing new contraceptives. It took Johnson two and a half years to raise the needed funds, via a reverse merger that took the company public. "There was so much education that was necessary," Johnson says, adding: "The landscape has changed considerably."

Johnson says she would like to think DARÉ had something to do with the shift, along with companies like Organon, a spinout of pharma company Merck that's focused on reproductive health. In surveying the fertility landscape, DARÉ saw limited non-hormonal options. On-demand options – like condoms – can detract from the moment. Copper IUDs must be inserted by a doctor and removed if a woman wants to return to fertility, and this method can have onerous side effects.

So, DARÉ created Ovaprene, a hormone-free device that's designed to be inserted into the vagina monthly by the user. The mesh product acts as a barrier, while releasing a chemical that immobilizes sperm. In an early study, the company reported that Ovaprene prevented almost all sperm from entering the cervical canal. The results, DARÉ believes, indicate high efficacy.

A late-stage study, slated to kick off next year, will be the true judge. Should Ovaprene eventually win regulatory approval, drug giant Bayer will handle commercializing the device.

Other new forms of birth control in development are further out, and that's assuming they perform well in clinical trials. Among them: a once-a-month birth control pill, along with a male version of the birth control pill. The latter is often brought up among women who say it's high time that men take a more proactive role in birth control.

For Summers, her search for a safe and convenient birth control continues. She tried Phexxi, which caused irritation. Still, she's excited that a non-hormonal option now exists. "I'm sure it will work for others," she says.

How dozens of men across Alaska (and their dogs) teamed up to save one town from a deadly outbreak

In 1925, health officials in Alaska came up with a creative solution to save a remote fishing town from a deadly disease outbreak.

During the winter of 1924, Curtis Welch – the only doctor in Nome, a remote fishing town in northwest Alaska – started noticing something strange. More and more, the children of Nome were coming to his office with sore throats.

Initially, Welch dismissed the cases as tonsillitis or some run-of-the-mill virus – but when more kids started getting sick, with some even dying, he grew alarmed. It wasn’t until early 1925, after a three-year-old boy died just two weeks after becoming ill, that Welch realized that his worst suspicions were true. The boy – and dozens of other children in town – were infected with diphtheria.

A DEADLY BACTERIA

Diphtheria is nearly nonexistent and almost unheard of in industrialized countries today. But less than a century ago, diphtheria was a household name – one that struck fear in the heart of every parent, as it was extremely contagious and particularly deadly for children.

Diphtheria – a bacterial infection – is an ugly disease. When it strikes, the bacteria eats away at the healthy tissues in a patient’s respiratory tract, leaving behind a thick, gray membrane of dead tissue that covers the patient's nose, throat, and tonsils. Not only does this membrane make it very difficult for the patient to breathe and swallow, but as the bacteria spreads through the bloodstream, it causes serious harm to the heart and kidneys. It sometimes also results in nerve damage and paralysis. Even with treatment, diphtheria kills around 10 percent of people it infects. Young children, as well as adults over the age of 60, are especially at risk.

Welch didn’t suspect diphtheria at first. He knew the illness was incredibly contagious and reasoned that many more people would be sick – specifically, the family members of the children who had died – if there truly was an outbreak. Nevertheless, the symptoms, along with the growing number of deaths, were unmistakable. By 1925 Welch knew for certain that diphtheria had come to Nome.

In desperation, Welch tried treating an infected seven-year-old girl with some expired antitoxin – but she died just a few hours after he administered it.

AN INACCESSIBLE CURE

A vaccine for diphtheria wouldn’t be widely available until the mid-1930s and early 1940s – so an outbreak of the disease meant that each of the 10,000 inhabitants of Nome were all at serious risk.

One option was to use something called an antitoxin – a serum consisting of anti-diphtheria antibodies – to treat the patients. However, the town’s reserve of diphtheria antitoxin had expired. Welch had ordered a replacement shipment of antitoxin the previous summer – but the shipping port that was set to deliver the serum had been closed due to ice, and no new antitoxin would arrive before spring of 1925. In desperation, Welch tried treating an infected seven-year-old girl with some expired antitoxin – but she died just a few hours after he administered it.

Welch radioed for help to all the major towns in Alaska as well as the US Public Health Service in Washington, DC. His telegram read: An outbreak of diphtheria is almost inevitable here. I am in urgent need of one million units of diphtheria antitoxin. Mail is the only form of transportation.

FOUR-LEGGED HEROES

When the Alaskan Board of Health learned about the outbreak, the men rushed to devise a plan to get antitoxin to Nome. Dropping the serum in by airplane was impossible, as the available planes were unsuitable for flying during Alaska’s severe winter weather, where temperatures were routinely as cold as -50 degrees Fahrenheit.

In late January 1925, roughly 30,000 units of antitoxin were located in an Anchorage hospital and immediately delivered by train to a nearby city, Nenana, en route to Nome. Nenana was the furthest city that was reachable by rail – but unfortunately it was still more than 600 miles outside of Nome, with no transportation to make the delivery. Meanwhile, Welch had confirmed 20 total cases of diphtheria, with dozens more at high risk. Diphtheria was known for wiping out entire communities, and the entire town of Nome was in danger of suffering the same fate.

It was Mark Summer, the Board of Health superintendent, who suggested something unorthodox: Using a relay team of sled-racing dogs to deliver the antitoxin serum from Nenana to Nome. The Board quickly voted to accept Summer’s idea and set up a plan: The thousands of units of antitoxin serum would be passed along from team to team at different towns along the mail route from Nenana to Nome. When it reached a town called Nulato, a famed dogsled racer named Leonhard Seppala and his experienced team of huskies would take the serum more than 90 miles over the ice of Norton Sound, the longest and most treacherous part of the journey. Past the sound, the serum would change hands several times more before arriving in Nome.

Between January 27 and 31, the serum passed through roughly a dozen drivers and their dog sled teams, each of them carrying the serum between 20 and 50 miles to the next destination. Though each leg of the trip took less than a day, the sub-zero temperatures – sometimes as low as -85 degrees – meant that every driver and dog risked their lives. When the first driver, Bill Shannon, arrived at his checkpoint in Tolovana on January 28th, his nose was black with frostbite, and three of his dogs had died. The driver who relieved Bill Shannon, named Edgar Kalland, needed the owner of a local roadhouse to pour hot water over his hands to free them from the sled’s metal handlebar. Two more dogs from another relay team died before the serum was passed to Seppala at a town called Ungalik.

THE FINAL STRETCHES

Seppala and his team raced across the ice of the Norton Sound in the dead of night on January 31, with wind chill temperatures nearing an astonishing -90 degrees. The team traveled 84 miles in a single day before stopping to rest – and once rested, they set off again in the middle of the night through a raging winter storm. The team made it across the ice, as well as a 5,000-foot ascent up Little McKinley Mountain, to pass the serum to another driver in record time. The serum was now just 78 miles from Nome, and the death toll in town had reached 28.

The serum reached Gunnar Kaasen and his team of dogs on February 1st. Balto, Kaasen’s lead dog, guided the team heroically through a winter storm that was so severe Kaasen later reported not being able to see the dogs that were just a few feet ahead of him.

Visibility was so poor, in fact, that Kaasen ran his sled two miles past the relay point before noticing – and not wanting to lose a minute, he decided to forge on ahead rather than doubling back to deliver the serum to another driver. As they continued through the storm, the hurricane-force winds ripped past Kaasen’s sled at one point and toppled the sled – and the serum – overboard. The cylinder containing the antitoxin was left buried in the snow – and Kaasen tore off his gloves and dug through the tundra to locate it. Though it resulted in a bad case of frostbite, Kaasen eventually found the cylinder and kept driving.

Kaasen arrived at the next relay point on February 2nd, hours ahead of schedule. When he got there, however, he found the relay driver of the next team asleep. Kaasen took a risk and decided not to wake him, fearing that time would be wasted with the next driver readying his team. Kaasen, Balto, and the rest of the team forged on, driving another 25 miles before finally reaching Nome just before six in the morning. Eyewitnesses described Kaasen pulling up to the town’s bank and stumbling to the front of the sled. There, he collapsed in exhaustion, telling onlookers that Balto was “a damn fine dog.”

A LIVING LEGACY

Just a few hours after Balto’s heroic arrival in Nome, the serum had been thawed and was ready to administer to the patients with diphtheria. Amazingly, the relay team managed to complete the entire journey in just 127 hours – a world record at the time – without one serum vial damaged or destroyed. The serum shipment that arrived by dogsled – along with additional serum deliveries that followed in the next several weeks – were successful in stopping the outbreak in its tracks.

Balto and several other dogs – including Togo, the lead dog on Seppala’s team – were celebrated as local heroes after the race. Balto died in 1933, while the last of the human serum runners died in 1999 – but their legacy lives on: In early 2021, an all-female team of healthcare workers made the news by braving the Alaskan winter to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to people in rural North Alaska, traveling by bobsled and snowmobile – a heroic journey, and one that would have been unthinkable had Balto, Togo, and the 1925 sled runners not first paved the way.

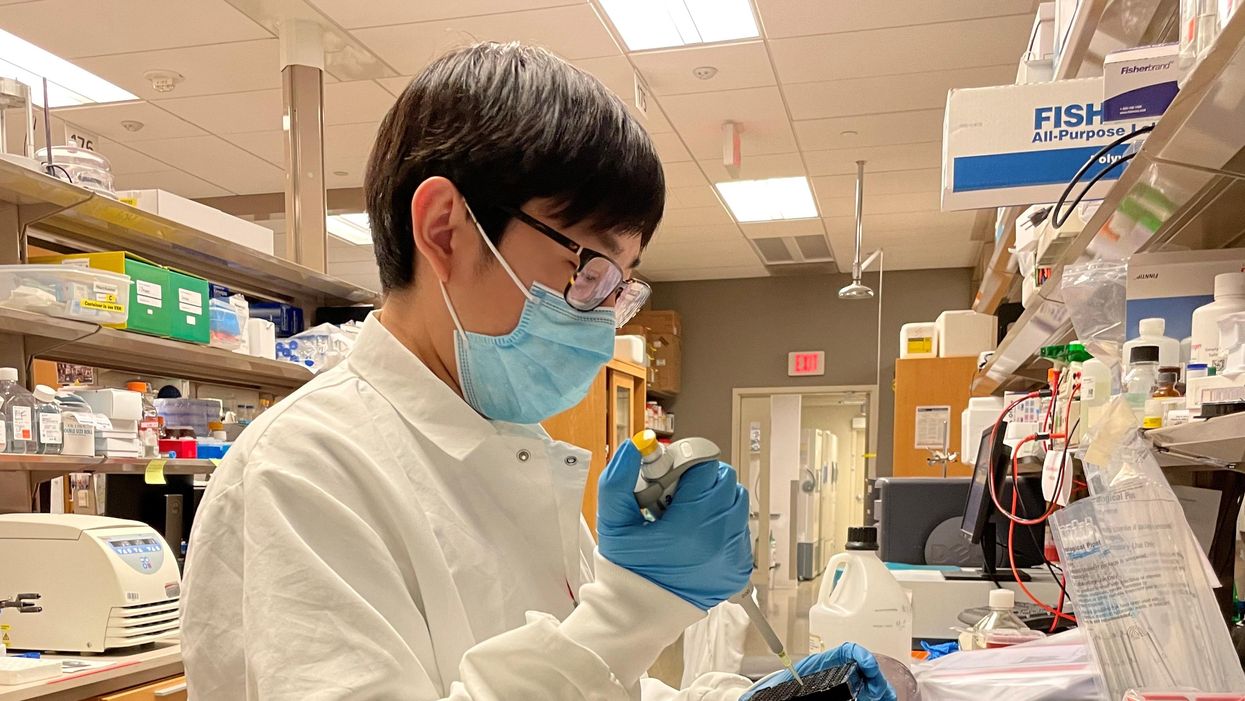

Jacob Brenner and his partners at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine are finding new ways to get nanomedicines to arrive at their targets.

Its strength is in its lack of size.

Using materials on the minuscule scale of nanometers (billionths of a meter), nanomedicines have the ability to provide treatment more precise than any other form of medicine. Under optimal circumstances, they can target specific cells and perform feats like altering the expression of proteins in tumors so that the tumors shrink.

Another appealing concept about nanomedicine is that treatment on a nano-scale, which is smaller yet than individual cells, can greatly decrease exposure to parts of the body outside the target area, thereby mitigating side effects.

But this young field's huge potential has met with an ongoing obstacle: the recipient's immune system tends to regard incoming nanomedicines as a threat and launches a complement protein attack. These complement proteins, which act together through a wave of reactions to get rid of troubling microorganisms, have had more than 500 million years to refine their craft, so they are highly effective.

Seeking to overcome a half-billion-year disadvantage, nanomaterials engineers have tried such strategies as creating so-called stealth nanoparticles.

“All new technologies face technical barriers, and it is the job of innovators to engineer solutions to them,” Brenner says.

Despite these clever attempts, nanomedicines largely keep failing to arrive at their intended destinations. According to the most comprehensive meta-analysis of nanomedicines in oncology, fewer than 1 percent of nanoparticles manage to reach their targets. The remaining 99-plus percent are expelled to the liver, spleen, or lungs – thereby squandering their therapeutic potential. Though these numbers seem discouraging, systems biologist Jacob Brenner remains undaunted. “All new technologies face technical barriers, and it is the job of innovators to engineer solutions to them,” he says.

Brenner and his fellow researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have recently devised a method that, in a study published in late 2021 involving sepsis-afflicted mice, saw a longer half-life of nanoparticles in the bloodstream. This effect is crucial because “the longer our nanoparticles circulate, the more time they have to reach their target organs,” says Brenner, the study's co-principal investigator. He works as a critical care physician at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, where he also serves as an assistant professor of medicine.

The method used by Brenner's lab involves coating nanoparticles with natural suppressors that safeguard against a complement attack from the recipient's immune system. For this idea, he credits bacteria. “They are so much smarter than us,” he says.

Brenner points out that many species of bacteria have learned to coat themselves in a natural complement suppressor known as Factor H in order to protect against a complement attack.

Humans also have Factor H, along with an additional suppressor called Factor I, both of which flow through our blood. These natural suppressors “are recruited to the surface of our own cells to prevent complement [proteins] from attacking our own cells,” says Brenner.

Coating nanoparticles with a natural suppressor is a “very creative approach that can help tone and improve the activity of nanotechnology medicines inside the body,” says Avi Schroeder, an associate professor at Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, where he also serves as Head of the Targeted Drug Delivery and Personalized Medicine Group.

Schroeder explains that “being able to tone [down] the immune response to nanoparticles enhances their circulation time and improves their targeting capacity to diseased organs inside the body.” He adds how the approach taken by the Penn Med researchers “shows that tailoring the surface of the nanoparticles can help control the interactions the nanoparticles undergo in the body, allowing wider and more accurate therapeutic activity.”

Brenner says he and his research team are “working on the engineering details” to streamline the process. Such improvements could further subdue the complement protein attacks which for decades have proven the bane of nanomedical engineers.

Though these attacks have limited nanomedicine's effectiveness, the field has managed some noteworthy successes, such as the chemotherapy drugs Abraxane and Doxil, the first FDA-approved nanomedicine.

And amid the COVID-19 pandemic, nanomedicines became almost universally relevant with the vast circulation of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, both of which consist of lipid nanoparticles. “Without the nanoparticle, the mRNA would not enter the cells effectively and would not carry out the therapeutic goal,” Schroeder explains.

These vaccines, though, are “just the start of the potential transformation that nanomedicine will bring to the world,” says Brenner. He relates how nanomedicine is “joining forces with a number of other technological innovations,” such as cell therapies in which nanoparticles aim to reprogram T-cells to attack cancer.

With a similar degree of optimism, Schroeder says, “We will see further growing impact of nanotechnologies in the clinic, mainly by enabling gene therapy for treating and even curing diseases that were incurable in the past.”

Brenner says that in the next 10 to 15 years, “nanomedicine is likely to impact patients” contending with a “huge diversity” of conditions. “I can't wait to see how it plays out.”