New Options Are Emerging in the Search for Better Birth Control

A decade ago, Elizabeth Summers' options for birth control suddenly narrowed. Doctors diagnosed her with Factor V Leiden, a rare genetic disorder, after discovering blood clots in her lungs. The condition increases the risk of clotting, so physicians told Summers to stay away from the pill and other hormone-laden contraceptives. "Modern medicine has generally failed to provide me with an effective and convenient option," she says.

But new birth control options are emerging for women like Summers. These alternatives promise to provide more choices to women who can't ingest hormones or don't want to suffer their unpleasant side effects.

These new products have their own pros and cons. Still, doctors are welcoming new contraceptives following a long drought in innovation. "It's been a long time since we've had something new in the world of contraception," says Heather Irobunda, an obstetrician and gynecologist at NYC Health and Hospitals.

On social media, Irobunda often fields questions about one of these new options, a lubricating gel called Phexxi. San Diego-based Evofem, the company behind Phexxi, has been advertising the product on Hulu and Instagram after the gel was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2020. The company's trendy ads target women who feel like condoms diminish the mood, but who also don't want to mess with an IUD or hormones.

Here's how it works: Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex. The gel regulates vaginal pH — essentially, the acidity levels — in a range that's inhospitable to sperm. It sounds a lot like spermicide, which is also placed in the vagina prior to sex to prevent pregnancy. But spermicide can damage the vagina's cell walls, which can increase the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

"Not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option."

Phexxi isn't without side effects either. The most common one is vaginal burning, according to a late-stage trial. It's also possible to develop a urinary tract infection while using the product. That same study found that during typical use, Phexxi is about 86 percent effective at preventing pregnancy. The efficacy rate is comparable to condoms but lower than birth control pills (91 percent) and significantly lower than an IUD (99 percent).

Phexxi – which comes in a pack of 12 – represents a tiny but growing part of the birth control market. Pharmacies dispensed more than 14,800 packs from April through June this year, a 65 percent increase over the previous quarter, according to data from Evofem.

"We've been able to demonstrate that not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option," says Saundra Pelletier, Evofem's CEO.

Beyond contraception, the company is carrying out late-stage tests to gauge Phexxi's effectiveness at preventing the sexually transmitted infections chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex.

Phexxi

A New Pill

The first birth control pill arrived in 1960, combining the hormones estrogen and progestin to stop sperm from joining with an egg, giving women control over their fertility. Subsequent formulations sought to ease side effects, by way of lower amounts of estrogen. But some women still experience headaches and nausea – or more serious complications like blood clots. On social media, women recently noted that birth control pills are much more likely to cause blood clots than Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine that was briefly paused to evaluate the risk of clots in women under age 50. What will it take, they wondered, for safer birth control?

Mithra Pharmaceuticals of Belgium sought to create a gentler pill. In April, the FDA approved Mithra's Nextstellis, which includes a naturally occurring estrogen, the first new estrogen in the U.S. in 50 years. Nextstellis selectively acts on tissues lining the uterus, while other birth control pills have a broader target.

A Phase 3 trial showed a 98 percent efficacy rate. Andrew London, an obstetrician and gynecologist, who practices at several Maryland hospitals, says the results are in line with some other birth control pills. But, he added, early studies indicate that Nextstellis has a lower risk of blood clotting, along with other potential benefits, which additional clinical testing must confirm.

"It's not going to be worse than any other pill. We're hoping it's going to be significantly better," says London.

The estrogen in Nexstellis, called estetrol, was skipped over by the pharmaceutical industry after its discovery in the 1960s. Estetrol circulates between the mother and fetus during pregnancy. Decades later, researchers took a new look, after figuring out how to synthesize estetrol in a lab, as well as produce estetrol from plants.

"That allowed us to really start to investigate the properties and do all this stuff you have to do for any new drug," says Michele Gordon, vice president of marketing in women's health at Mayne Pharma, which licensed Nextstellis.

Bonnie Douglas, who followed the development of Nextstellis as part of a search for better birth control, recently switched to the product. "So far, it's much more tolerable," says Douglas. Previously, the Midwesterner was so desperate to find a contraceptive with fewer side effects that she turned to an online pharmacy to obtain a different birth control pill that had been approved in Canada but not in the U.S.

Contraceptive Access

Even if a contraceptive lands FDA approval, access poses a barrier. Getting insurers to cover new contraceptives can be difficult. For the uninsured, state and federal programs can help, and companies should keep prices in a reasonable range, while offering assistance programs. So says Kelly Blanchard, president of the nonprofit Ibis Reproductive Health. "For innovation to have impact, you want to reach as many folks as possible," she says.

In addition, companies developing new contraceptives have struggled to attract venture capital. That's changing, though.

In 2015, Sabrina Johnson founded DARÉ Bioscience around the idea of women's health. She estimated the company would be fully funded in six months, based on her track record in biotech and the demand for novel products.

But it's been difficult to get male investors interested in backing new contraceptives. It took Johnson two and a half years to raise the needed funds, via a reverse merger that took the company public. "There was so much education that was necessary," Johnson says, adding: "The landscape has changed considerably."

Johnson says she would like to think DARÉ had something to do with the shift, along with companies like Organon, a spinout of pharma company Merck that's focused on reproductive health. In surveying the fertility landscape, DARÉ saw limited non-hormonal options. On-demand options – like condoms – can detract from the moment. Copper IUDs must be inserted by a doctor and removed if a woman wants to return to fertility, and this method can have onerous side effects.

So, DARÉ created Ovaprene, a hormone-free device that's designed to be inserted into the vagina monthly by the user. The mesh product acts as a barrier, while releasing a chemical that immobilizes sperm. In an early study, the company reported that Ovaprene prevented almost all sperm from entering the cervical canal. The results, DARÉ believes, indicate high efficacy.

A late-stage study, slated to kick off next year, will be the true judge. Should Ovaprene eventually win regulatory approval, drug giant Bayer will handle commercializing the device.

Other new forms of birth control in development are further out, and that's assuming they perform well in clinical trials. Among them: a once-a-month birth control pill, along with a male version of the birth control pill. The latter is often brought up among women who say it's high time that men take a more proactive role in birth control.

For Summers, her search for a safe and convenient birth control continues. She tried Phexxi, which caused irritation. Still, she's excited that a non-hormonal option now exists. "I'm sure it will work for others," she says.

7 Reasons Why We Should Not Need Boosters for COVID-19

A top infectious disease physician explains why immunity derived from natural infection and the vaccines should be long-lasting.

There are at least 7 reasons why immunity after vaccination or infection with COVID-19 should likely be long-lived. If durable, I do not think boosters will be necessary in the future, despite CEOs of pharmaceutical companies (who stand to profit from boosters) messaging that they may and readying such boosters. To explain these reasons, let's orient ourselves to the main components of the immune system.

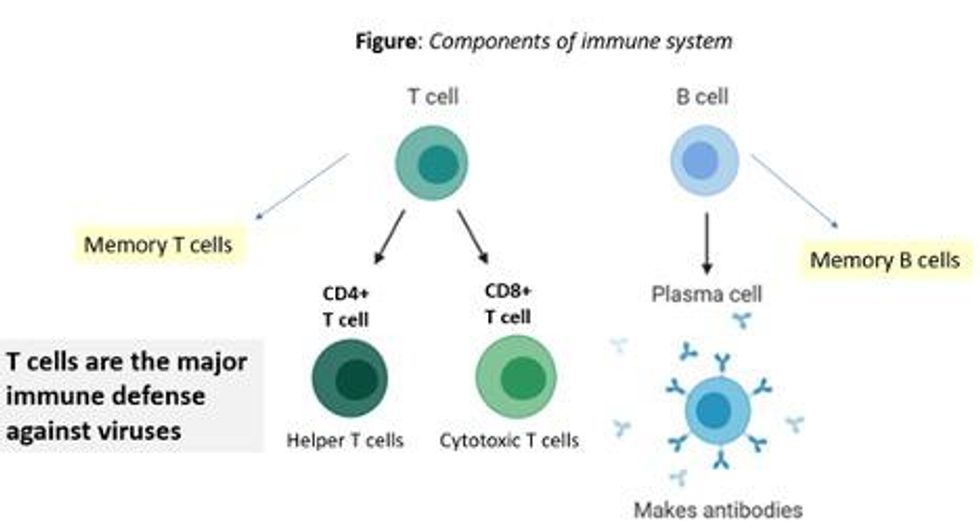

There are two major arms of the immune system: B cells (which produce antibodies) and T cells (which are formed specifically to attack and kill pathogens). T cells are divided into two types, CD4 cells ("helper" T cells) and CD8 cells ("cytotoxic" T cells).

Each arm, once stimulated by infection or vaccine, should hopefully make "memory" banks. So if the body sees the pathogen in the future, these defenses should come roaring back to attack the virus and protect you from getting sick. Plenty of research in COVID-19 indicates a likely long-lasting response to the vaccine or infection. Here are seven of the most compelling reasons:

REASON 1: Memory B Cells Are Produced By Vaccines and Natural Infection

In one study, 12 volunteers who had never had Covid-19--and were fully vaccinated with two Pfizer/BioNTech shots-- underwent biopsies of their lymph nodes. This is where memory B cells are stored in places called "germinal centers". The biopsies were performed three, four, six, and seven weeks after the first mRNA vaccine shot, and were stained to reveal that germinal center memory B cells in the lymph nodes increased in concentration over time.

Natural infection also generates memory B cells. Even after antibody levels wane over time, strong memory B cells were detected in the blood of individuals six and eight months after infection in different studies. Indeed, the half-lives of the memory B cells seen in the study examining patients 8 months after COVID-19 led the authors to conclude that "B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 was robust and is likely long-lasting." Reason #2 tells us that memory B cells can be active for a very long time indeed.

REASON #2: Memory B Cells Can Produce Neutralizing Antibodies If They See Infection Again Decades Later

Demonstrated production of memory B cells after vaccination or natural infection with COVID-19 is so important because memory B cells, once generated, can be activated to produce high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the pathogen even if encountered many years after the initial exposure. In one amazing study (published in 2008), researchers isolated memory B cells against the 1918 flu strain from the blood of 32 individuals aged 91-101 years. These people had been born on or before 1915 and had survived that pandemic.

Their memory B cells, when exposed to the 1918 flu strain in a test tube, generated high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the virus -- antibodies that then protected mice from lethal infection with this deadly strain. The ability of memory B cells to produce complex antibody responses against an infection nine decades after exposure speaks to their durability.

REASON #3: Vaccines or Natural Infection Trigger Strong Memory T Cell Immunity

All of the trials of the major COVID-19 vaccine candidates measured strong T cell immunity following vaccination, most often assessed by measuring SARS-CoV-2 specific T cells in the phase I/II safety and immunogenicity studies. There are a number of studies that demonstrate the production of strong T cell immunity to COVID-19 after natural infection as well, even when the infection was mild or asymptomatic.

The same study that showed us robust memory B cell production 8 months after natural infection also demonstrated strong and sustained memory T cell production. In fact, the half-lives of the memory T cells in this cohort were long (~125-225 days for CD8+ and ~94-153 days for CD4+ T cells), comparable to the 123-day half-life observed for memory CD8+ T cells after yellow fever immunization (a vaccine usually given once over a lifetime).

A recent study of individuals recovered from COVID-19 show that the initial T cells generated by natural infection mature and differentiate over time into memory T cells that will be "put in the bank" for sustained periods.

REASON #4: T Cell Immunity Following Vaccinations for Other Infections Is Long-Lasting

Last year, we were fortunate to be able to measure how T cell immunity is generated by COVID-19 vaccines, which was not possible in earlier eras when vaccine trials were done for other infections (such as measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, diphtheria). Antibodies are just the "tip of the iceberg" when assessing the response to vaccination, but were the only arm of the immune response that could be measured following vaccination in the past.

Measuring pathogen-specific T cell responses takes sophisticated technology. However, T cell responses, when assessed years after vaccination for other pathogens, has been shown to be long-lasting. For example, in one study of 56 volunteers who had undergone measles vaccination when they were much younger, strong CD8 and CD4 cell responses to vaccination could be detected up to 34 years later.

REASON #5: T Cell Immunity to Related Coronaviruses That Caused Severe Disease is Long-Lasting

SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus that causes severe disease, unlike coronaviruses that cause the common cold. Two other coronaviruses in the recent past caused severe disease, specifically Severely Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (SARS) in late 2002-2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2011.

A study performed in 2020 demonstrated that the blood of 23 recovered SARS patients possess long-lasting memory T cells that were still reactive to SARS 17 years after the outbreak in 2003. Many scientists expect that T cell immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will be equally durable to that of its cousin.

REASON #6: T Cell Responses from Vaccination and Natural Infection With the Ancestral Strain of COVID-19 Are Robust Against Variants

Even though antibody responses from vaccination may be slightly lower against various COVID-19 variants of concern that have emerged in recent months, T cell immunity after vaccination has been shown to be unperturbed by mutations in the spike protein (in the variants). For instance, T cell responses after mRNA vaccines maintained strong activity against different variants (including P.1 Brazil variant, B.1.1.7 UK variant, B.1.351 South Africa variant and the CA.20.C California variant) in a recent study.

Another study showed that the vaccines generated robust T cell immunity that was unfazed by different variants, including B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. The CD4 and CD8 responses generated after natural infection are equally robust, showing activity against multiple "epitopes" (little segments) of the spike protein of the virus. For instance, CD8 cells responds to 52 epitopes and CD4 cells respond to 57 epitopes across the spike protein, so that a few mutations in the variants cannot knock out such a robust and in-breadth T cell response. Indeed, a recent paper showed that mRNA vaccines were 97.4 percent effective against severe COVID-19 disease in Qatar, even when the majority of circulating virus there was from variants of concern (B.1.351 and B.1.1.7).

REASON #7: Coronaviruses Don't Mutate Quickly Like Influenza, Which Requires Annual Booster Shots

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses, like influenza and HIV (which is actually a retrovirus), but do not mutate as quickly as either one. The reason that coronaviruses don't mutate very rapidly is that their replicating mechanism (polymerase) has a strong proofreading mechanism: If the virus mutates, it usually goes back and self-corrects. Mutations can arise with high rates of replication when transmission is very frequent -- as has been seen in recent months with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants during surges. However, the COVID-19 virus will not be mutating like this when we tamp down transmission with mass vaccination.

In conclusion, I and many of my infectious disease colleagues expect the immunity from natural infection or vaccination to COVID-19 to be durable. Let's put discussion of boosters aside and work hard on global vaccine equity and distribution since the pandemic is not over until it is over for us all.

Professor Tim Caulfield stops by the "Making Sense of Science" podcast this month to discuss the infodemic around COVID-19 and how to deal with it.

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

Hear the 30-second trailer:

Listen to the whole episode:

.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.