New Podcast: "Making Sense of Science"

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Making Sense of Science features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

Episode 1: "COVID-19 Vaccines and Our Progress Toward Normalcy"

Bioethicist Arthur Caplan of NYU shares his thoughts on when we will build herd immunity, how enthusiastic to be about the J&J vaccine, predictions for vaccine mandates in the coming months, what should happen with kids and schools, whether you can hug your grandparents after they get vaccinated, and more.

Transcript:

KIRA: Hi, and welcome to our new podcast 'Making Sense of Science', the show that features interviews with leading experts in health and science about the latest developments and the big ethical questions. I'm your host Kira Peikoff, the editor of leaps.org. And today, we're going to talk about the Covid-19 vaccines. I'm honored that my first guest is Dr. Art Caplan of NYU, one of the world's leading bio-ethicists. Art, thanks so much for joining us today.

DR. CAPLAN: Thank you so much for having me.

KIRA: So the big topic right now is the new J&J vaccine, which is likely to be given to millions of Americans in the coming weeks. It only requires one-shot, it can be stored in refrigerators for several months. It has fewer side-effects and most importantly, it is extremely effective at the big things, preventing hospitalizations and deaths. Though not as effective as Pfizer and Moderna in preventing moderate cases, especially potentially in older adults with underlying conditions. So Art, what's your take overall, on how enthusiastic Americans should be about this vaccine?

DR. CAPLAN: I'm usually enthusiastic. The more weapons, the better. This vaccine, while maybe, slightly less efficacious than the Moderna and the Pfizer ones, is easier to make, is easier to ship. It's one-shot. You know, here there's already been problems of getting people to come back in for their second shots. I would say 5... 7% of people don't show up even though you remind them and you nag them, they don't come back. So a one-shot option is great. A one-shot option that's easy to, if you will, brew up in your rural pharmacy without having to have special instructions is great. And I think it's gonna really facilitate herd-immunity, meaning, we'll see millions and millions and millions of doses of the Janssen vaccine out there as an option, I'm gonna say, summer.

KIRA: Great. And to be fair, it's worth mentioning that the J&J vaccine was tested in clinical trials after variants began to circulate, and it's only one-shot instead of two, like the other vaccines, and it gets more effective over time. So is it really fair to directly compare its efficacy to the mRNA vaccines?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, you know, people are gonna do that. And one issue that'll come up ethically is people are gonna say, "Can I choose my vaccine? I want the most efficacious one. I want the name brand that I trust. I don't want the new platform. I like Janssen's 'cause it's an older, more established way to make vaccines or whatever." Who knows what cuckoo-cockamamie reasons they might have. To me, you take what you can get, it'll be great. It's way above what we normally would expect, those 95% success rates are off the charts. Getting something that's 70% effective, it's perfectly wonderful. I wish we had flu shots that were 70% effective.

And the other thing to keep in mind is we're gonna see more mutations, we're gonna see more strains. That's just a reality of viruses. So they'll mutate, more strains will appear, we can't just say, "Oh my goodness. There's a South-African one or the California one or the UK one. We better... I don't know, do something different." We're just gonna have to basically resign ourselves, I think, to boosters. So right now, take the vaccine. I'm almost tempted to say, "Shut up and take the vaccine. Don't worry about choosing."

Just get what you can get. If you live in a rural community and all they have is Janssen, take it. If you're in another country and all they ship to you is Janssen, take it. And then we'll worry about the next round of virus mutations, if you will, when we get to the boosters. I'm more concerned that these things aren't gonna last more than a year or two than I am that they're not gonna pick up every mutation.

KIRA: So on that note, shipping to rural places or low-income countries that lack the ultra-cold freezers that you need for the super effective mRNA vaccines, the Janssen vaccine seems like a really great option, but are we going to encounter a potential conflict of people saying, "Well, there's "poor or rich vaccines," and one is slightly less effective than the other." And so are we gonna disenfranchise people and undermine their actual willingness to take the vaccine?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, it's interesting. I think the first problem is gonna be, "I have vaccine and I don't have any vaccine," between rich and poor countries. Look, the poor countries are screaming to get vaccine supply sent to them. I think, for example, Ghana received recently 600 million doses of AstraZeneca vaccine. It was freed up by South Africa, which decided they didn't wanna use it 'cause they thought there was "a better vaccine" coming. So even among the poorer nations or the developing nations, some vaccines are getting typed as the not-as-good or the less-desirable... We've already started to see it.

But for the most part, the rich countries are gonna try and vaccinate to herd immunity, you can argue about the ethics of whether that's right, before they start sharing. And I think we'll have haves and have-nots, herd immunity produced in the rich countries, Japan, North America, Europe, by the end of the year anyway. And still some countries floundering around saying, "I didn't get anything," and what are you gonna do?

KIRA: And I know you said to people, which is a very memorable quote, "just shut up and take the vaccine, whatever you can get, whatever is available to you now, do it." But inevitably, as you mentioned, some people are going to say, "Well, I just wanna wait to get the best one possible." When will people have a choice in vaccines, do you think?

DR. CAPLAN: I don't think you'll see that till next year. I think we're gonna see distribution according to where the supply chains are that the vaccine manufacturers use. So if I use McKesson and they ship to the Northeast, and that's where my vaccine goes, that's what's available there. If I'm contracted to Walmart and they buy Janssen, that's what you're gonna see at the big box store. I don't think you're really gonna get too much in the way of choice until next year, when then they're gonna say they ship three different kinds of vaccine, and I can offer you one dose or two dose... One of them lasts a year, one of them lasts 18 months. I don't think we're gonna have the informed choice until next year.

KIRA: Okay. And right now the steep demand is outstripping the supply, and there's been a lot of pressure put on the vaccine makers to ramp up as quickly as possible. Of course, they say that they're doing that and the government is pressuring them to do that, but when do you think we'll cross over to the point where vaccine hesitancy is a bigger issue than vaccine demand?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. So this is a really interesting issue. I'm glad you asked me this because I think it's got good foresight. The big ethics fight now is scarcity and who goes first, and the ethicists, including me, are having a fine old time arguing about healthcare workers versus policemen versus people who work for UPS versus somebody who's working at the drug store. Who's more important? Why are they more important? Who's essential?

Actually, I think most of that is nonsense, because what we've learned is that you can't do much in the way of micro-allocation, the system strains, and it doesn't work. You've gotta use some pretty broad categories like over 65, still breathing and working, and a kid. The kid will go last, 'cause we don't have the data, everybody else should get in line and the over 65s should probably be first 'cause they're at high risk. We can't do this. We stink at the micro-management of vaccine supply, plus it encourages cheating. So everybody's out there with vaccine hunters, vaccine tourism, bribing, lying, dressing up like a grandmother to get a vaccine. My favorite one was some rich people in Vancouver flew up to the Yukon and pretended to be Inuit aboriginal people to get a vaccine. That will all pass.

We'll have enough vaccine by the summer, more or less, that the issue will then be, "How are we gonna get to herd immunity or at least maximal immunity, knowing that we don't have data on kids?" People under 18, I think are something like 20% of our population. That means the best you could do is 80%. The other population still could be passing the virus, kids here or Europe or wherever. Well, the military refusal rate that I just saw was 30% saying no. I've heard nursing home staff rates, nursing attendants, nursing aids up at 40% to 50% saying no. So these are huge refusal rates, people are nervous about how it works, the vaccine. Some of them are like, "Well Art you take it. If you're still alive in six months, then maybe I'll take it, but I wanna see that it really works and it's safe." And other people say, "We don't wanna be exploited. We don't trust the government, whatever, to offer us these vaccines."

I'm gonna answer that was a long-winded way of saying we're gonna see some mandates, we're gonna see some coercions start to show up in the vaccine supply, because I think, for example, the military. The day one of these license gets... Excuse me, one of these vaccines get licensed, right now they're on an emergency approval, collect data for three or four more months, get the FDA to formally license the thing. I'd say between five minutes and 10 minutes, the military will be mandating. They have no interest in your objection, they have no interest in your choice, they know what the mission is. It's traditionally, we're gonna get you as healthy as we can to fight a war.

The fact that you say, "Gee, I might die." They kind of say, "Yeah, we noticed that, but that's in the military culture. We fight wars and do stuff like that." So they'll be mandating, I think, very rapidly. And I think healthcare workers will. I think most hospitals are gonna say 50% refusal rate among this nursing group? Forget it. We can't risk that. Nursing homes have been devastated by COVID. They're not gonna have aids out there unvaccinated. The only thing holding up the mandates right now is that we don't have full licensure. We have emergency use approvals, and that's good.

But it's a little tough to mandate without full license. The day we get it, three months, four months, we're gonna start to see mandates. And I'll make one more prediction, as long as I'm in a crystal ball mode. It won't be the government at that point that says, you have to be vaccinated. It'll be private business, 'cause they're gonna say, "You know what? Come on my cruise ship, 'cause everybody who works here is vaccinated." "Come on into my bar, everybody who works here is vaccinated." They're gonna start to use it as an advertising marketing lure. "It's safe here. Come on in." So I think they'll say, "If you wanna work on an airline as a flight attendant, you get vaccinated. We have vaccine proof. You can show it on your iPhone, on your whatever, you have a card that you did it." And so I think we'll see many businesses moving to vaccinate so that they can bring their customers back in.

KIRA: So private businesses, that's one thing, because people do not have to patronize those places if they don't wanna get vaccinated. But of course, this is gonna open up a can of worms with schools. Public schools, if they mandate teacher vaccines and you have to send your kid to school and you have to go to work at a school. What happens then?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, schools are gonna be at the end of the line. That's where we have the least data. So I don't think we're gonna see school mandates on kids, maybe not till next year. But we already have school mandates on kids. They were the first group to feel the force of mandates, because it turns out that measles and mumps and whooping cough are easy to get at school, sneezing and coughing on one another. Some states have added flu shots. Many states, California, Maine, New York have actually eliminated exemptions. The only way out for those kids is if they have a health reason. They're not even allowing religious or so-called philosophical or personal choice exemptions. COVID vaccines will just line up right next to those things.

Teachers will demand it, the pressure will be there. We'll have a lot of information by next year on safety. I'm even gonna say people are gonna be less tolerant of non-vaccinators. Now it's sort of like, "Wow. Yeah, I guess." But this time next year, if you haven't vaccinated, people are gonna come to your house and board it up and make you stay inside.

KIRA: Well, given how much we're so dependent on these vaccines to get us back to a regular life, I can understand the sentiment. What is your take on the big controversy right now, just going back towards the present day a little bit more on having kids in schools. Is that something you support before all the teachers have been vaccinated?

DR. CAPLAN: I do, but I have a problem with the definition of a teacher and a school. So by the way, some people that I know, friends of mine have said, "Well, I'm a teacher, I'm a yoga instructor. I'm a teacher, I'm an aerobics instructor. So I should get priority access to vaccination." I don't think that's what we meant by teacher. And here's the difference in schools. I live in Ridgefield, Connecticut. Up the street for me is a very fancy private elementary school. It has endless grounds, open classrooms. If there are eight kids in a class, I'll pass out. It is great. I wish I went to college there. It's a wonderful set up. Do they need to vaccinate everybody? Probably not, they're all sitting six feet apart, everybody in there is gonna mask, they have huge auditoriums. They never have to come in contact.

I've been in some other schools in the Bronx. No ventilation, no plumbing, 35 kids in a class, the teacher's 65. And you sort of think, "Boy, I'd wanna have vaccinate everybody in sight in this place because unless we re-haul the buildings and downsize the class size, people are gonna get sick in here."

They probably were getting sick anyway before COVID, but now COVID makes it worse. They're probably getting the flu or colds at nine times the rate that they were in Ridgefield, Connecticut. So my point is this, high school kids doing certain things, they can come in on a mixed schedule three days a week, two days a week, do their thing, they know how to mask. Am I worried about vaccinating there? Not too much. Elementary school kids need psychosocial development, need to learn social skills, sometimes going to schools that aren't that wonderful. Yeah, let's vaccinate them. So even though I was complaining a bit about micro-management and trying to parse out, here I think you need to do it. I think you're probably gonna say college, I don't know that you have to vaccinate there. High schools, 50/50. Elementary school, let's do them first.

KIRA: Got it. And one more question on kids before I wanna move on, there's been talk about whether it's necessary before kids are allowed to get this vaccine to have the FDA go to full approval with the full bulk of data necessary for that versus just an emergency authorization for the general population, given that kids are at so much lower risk than adults. But then of course, it'll take a lot more time, I imagine, to get the kids the vaccines. What's your take on that?

DR. CAPLAN: We historically have demanded higher levels of evidence to do anything with a kid, and I think that's gonna hold true here too. I don't think you're gonna see emergency-use authorization for people under 18. Maybe they'd cut it and say, "We'll do it 12-18," but just looking at the history of drug development, vaccine development, people are really leery of taking risks with kids and appropriately so. Kids can't even make their own decision. I can decide if I wanna take an emergency-use vaccine, if I think it's too iffy I don't take it right now. So up to me to weigh the risk-benefit. I don't think so. I think you'll see licensing required before we really get it, at least 12 and under. Let's put it there. And I'm not worried about the safety or efficacy of these things in kids. I think there's no reason, given the biological mechanisms, to think they're gonna be any different. But it's gonna be pretty tough pre-licensure to impose anything.

KIRA: And when do you think that licensure for kids under 12 could come?

DR. CAPLAN: Well, two groups of people are now being studied, pregnant women, the studies just launched. They'll probably be done sufficiently by the end of the year. Kids for full licensure, spring next year.

KIRA: Okay. And because this is a big question for a lot of women that I know and women in general who are pregnant, what would you say to them now, where we don't have the data yet on the safety, but they have to decide and they can't wait six or nine more months?

DR. CAPLAN: Vaccinate yesterday. Literally, I think the COVID virus is too dangerous, I think it's dangerous to the mom, I think it's dangerous to the fetus. It is an unknown, but boy, I would bet on the vaccine more than I would taking my chances with the virus.

KIRA: Got it. So let's pivot a little bit and talk about some of the big open questions around the vaccines that we're starting to get some early evidence about. For one thing, do they prevent transmission and not just symptomatic disease. And I think it's worth pointing out for our audience here that there is a big difference between preventing symptoms and preventing infections, as lots of asymptomatic people know. And we have a lot of new real-world evidence from Israel, from Scotland, reporting that even asymptomatic infections are greatly reduced by the Pfizer vaccine, for example. What is your take on how this new data is going to change guidance around post-vaccination behaviors?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. What do we got in the podcast? Seven or eight hours to go? That's a tough one. It's complicated. But trying to over-simplify a little bit. So there is a difference, and this has gotten confusing, I fear. Some vaccines prevent you from getting infected at all. It looks like the Pfizer and the Moderna fall into that category. That's great, 'cause no matter what else, it probably means you're gonna reduce transmission, 'cause if you can't be infected, I don't know how you're gonna give it to somebody else. So I'll bet that that's a transmission reduction. Looks like Johnson & Johnson, unclear. Seems to prevent bad symptoms and death but not moderate disease, and it isn't clear that it stops you from getting infected. So that may become an issue in terms of how we strategically approach when we have enough vaccine of the different types. We may wanna say, "Look, in some environments, we've gotta control spread... Nursing home. We wanna see the Moderna there. We wanna see the Pfizer there."

In other situations, we just wanna make sure you're not dead, let's get the Janssen thing out there. And that'll be great. I'll tell you... I'll give you an example from my own current existence. So I've been pretty cautious... As I said, I live in Ridgefield, Connecticut. I have a house, pretty roomy, but I haven't left it very often. I'm willing to take the chance to go shopping. I'll confess I'm even willing to take the chance wearing a mask to go to the drug store and I've had a hair-cut or two. So I've been not hyper-cautious, but cautious. I don't invite people over that I don't know where they've been, so to speak. But now I'm vaccinated, and my wife is fully vaccinated. And the other night for the first time, we went out to an indoor restaurant. Probably haven't done that in 10 months... No, I don't know, six months. But a long time...

KIRA: I hope you really enjoyed that first meal out, 'cause that's something that I dream about. Boy, where am I gonna go and what am I gonna order?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. We went to the fanciest restaurant in town, as a matter of fact, and they were social distancing and everybody was masked and the wait staff. But I figure, good enough for me. If the thing isn't gonna kill me, if I was just told I was gonna have a risk of being sick for three days or something, that's good enough for me. I don't wanna infect somebody else. So I'll still mask and do that, I'm not sure. But I'm absolutely ready to say, and in fact, I've scheduled two trips. We're gonna take a trip to Florida, we're gonna take a trip to North Carolina in March and April. I'm figuring even then, things will be better. But everybody's gonna have choices like that to make. It'll be really interesting. If I'm Tony Fauci or one of our big public health guys, I don't want anybody going anywhere, I'm risk-averse, until maybe 2027. I think it'll be controlled and eliminated... We'll have lots of data and everything will be great. I'm a little bit more, shall we say, individual choice-oriented, making individual risk things, like I said. As long as I'm responsible to others.

I don't wanna make anybody else sick, but if I am ready to take the chance of just being sick for a few days, and I believe the vaccines available will keep me out of the hospital and keep me out of the Morticians building. Okay, I'm ready to do it. So each one of us is gonna have to make a value decision, this is what I find interesting, about what's normal. It isn't science. It isn't medicine. It's ethics. You're gonna have to decide how much risk do you wanna take. Do you wanna be a jerk to your neighbor, if you could still have a teeny chance of infecting them? Am I willing to live in a world where COVID is around but it's kinda rare? I know kids are still transmitting, but it's not really a huge risk. That's the kind of value choice that each of us will be faced with.

KIRA: I really appreciate your emphasis on individual choice and values here and letting... Basically allowing people to make those judgments based on their circumstances for themselves. If you're not deathly afraid of getting a mild cold-type illness, then I can understand why you wanna fly or go to a restaurant, and other people might not be comfortable with any risk at all, and they're perfectly welcome to stay home.

DR. CAPLAN: Or they may say, "I'm 80, I have nine chronic diseases. A mild illness still freaks me out." Okay, I get that. I'm perfectly respectful of that. It's interesting. I think we've been used to public health messaging, and people have this attitude that at some point, Fauci or the head of the CDC, somebody's gonna show up on TV and say, "All clear, everything's over, back to normal, we've declared victory over the enemy. It's armistice day." Whatever. It isn't gonna work like that is my prediction. It's gonna be a slow creep, different people deciding, "I'm safe enough, I'm wandering out." Other people say, "No, no, not ready." Or somebody saying, "I'm pregnant. I'm staying in. I don't care what's going on. I'm not gonna take that risk." I think people will be surprised that there isn't going to be a national day of resolution or something. [chuckle]

KIRA: Right. It's more about these individual behaviors and over time, letting people decide what to do. So for example, if you had grandkids and they were not vaccinated, but you are, would you hug them, would you get close to them, how would you behave and how do you think they should behave around you?

DR. CAPLAN: So I'd be still nervous about them transmitting, but I'm also a very strong believer in my vaccine. So yes, I would hug them, and yes, I would have them come to visit. And that's probably gonna happen actually fairly soon. But their parents aren't vaccinated yet. And so I'm still nervous that maybe better not to do a lot of social mingling right now. But yeah, people have said to me, "My grandmom is 94. I don't know how long she's gonna be here. You think if I'm vaccinated it's okay to pay a visit." I'm gonna start to say, "Yeah, I get that."

KIRA: And I think one thing that's lost in these discussions of safety is also the aspect of benefits to human life and why we even live in the first place. We don't live lives of complete safety. We drive, we fly, we do things that are risky, but we take those risks, because it's worth it. So I think that should be part of the discussion overall, not just safety, period.

DR. CAPLAN: And not just saving lives. So ski slopes, there are a lot of orthopedic clinics at the bottom of big ski slopes, and sending a message like, "You can break bones here." But people say, "I wanna do it, I enjoy it." Okay, I'm not sure all the time that we should factor all of that into our pooled insurance plan, but that's a fight for another day. Nonetheless, I would... You know something, I would pay for it 'cause I like to encourage people to enjoy themselves. So I have my bad habits, they have their bad habits. I think it's sort of a wash in a certain way. But more to your point, I think if you look out there and say, there are some areas where we don't let you choose. You must put your kid in a car seat. A kid can't make a decision, the thing is very effective, really saves their lives, they should have a life ahead of them, and we're gonna force it. And I'm all for that.

In other instances, I might go into the restaurant. I think it's part of the general, "Am I gonna drive a car, am I gonna cross a busy street... " As you said, there are many things I have to do where I have to think about the risk-benefit. I may make a lousy calculation and underestimate what it means to get in my car and drive in terms of risk relative to getting hit by lightening or some other risks, but that's a little bit more for me.

KIRA: So that's a really thought-provoking conversation, but I wanna switch for a minute to another question mark around the vaccines besides transmission, is the long-term studies of their effects on the immune system. And one thing that I've noticed some experts are concerned about is the fact that a lot of the people in the placebo groups have dropped out of the trials and gotten the vaccine because ethically you can't withhold the vaccinations from these volunteers, but at the same time, that could be hurting our ability to compare the vaccine's long-term effects against people who haven't had the vaccine for a long time. So how significant is this issue in your mind?

DR. CAPLAN: Big. Some people actually proposed that we not let them drop out, we not tell the subjects in these big trials of vaccines if they were in the placebo group. Can't do that. It's clearly unethical... Achieved consensus on that decades ago, with various studies where the researcher said, "We don't have to tell the subjects that there's a treatment." Tuskegee did that, for example, the horrible study in the early, late '60s, early '70s, where they didn't tell people there was a cure and kept the study going of venereal disease, but there have been many others since. We already know you gotta give them the option. Some people may stay in anyway, but not enough to allow the study to really have integrity. So I think current studies are likely to fall apart and we won't get answers in the way we're used to with randomized trials to the long-term effects or even to the how long does it last question.

We need to build a system that can follow people. We can't rely on them being in an observed clinical trial. We have to start to say, "You register, we're gonna check on you every year to see how you're doing." That's gotta be done. And one other provocative idea, I pushed it long ago, challenge studies. Deliberately infect a small group of people, hopefully healthy people that choose to do it with mild COVID and then see what the vaccine does in them and then get an answer faster if you study them over time, they volunteered knowingly to get exposed this way. I think you're gonna see some challenge studies done particularly to compare vaccines. There are still more vaccines coming, maybe some of them will last longer, cheaper, safer, I don't know. The only way you're gonna study the next round of vaccines is in a challenge study. You're never getting anybody to sign up to be in a placebo control randomized trial.

KIRA: So that was actually my next question, that the UK just approved the first ever challenge study to infect the volunteers on purpose with the virus. Now, the UK has often been much more progressive in doing medical research than the US. Do you think the US will ever get to that point or are we just gonna rely on other countries to do that for us?

DR. CAPLAN: I think we won't get there. We're so conservative, so litigation conscious. People are freaked out that if somebody got sick and died in a challenge study, it would bankrupt the sponsor. I think the UK is on the right path, but I don't really think we're gonna follow.

KIRA: Okay, well, I hope that they can do the work that we really need. And I'm grateful that there are other countries that are more permissive of risk-taking and doing the controversial studies that are required.

DR. CAPLAN: Ironically, if you don't do the challenge studies, the only other way you're gonna get to do big-scale randomized placebo trials is in the poorest countries that can't get anything. And that makes it an awful lot like exploitation, taking advantage, as opposed to choice. But that's where you'd go, you'd say, "Oh, I got this new vaccine, I'll test it out in Sierra Leone and they don't have anything anyway. So better that half of them get the vaccine than not." And I still think the challenge study makes more ethic sense.

KIRA: Yeah, absolutely. That would really be a shame to be put in that position instead of just allowing people to decide. We let people sign up for the army where they might die. What's the ethical difference with signing up for a potentially dangerous study, but if you're young and healthy, the risk is low?

DR. CAPLAN: By the way, the risk from COVID to say, 18 to 35-year-olds, who's who you'd be looking at, is about the same as donating a kidney, which we also allow all the time.

KIRA: Right, right. Great point. Before we finish up here, I just wanna quickly touch on, of course, the big elephant in the room, which we all have to deal with, unfortunately, which is the variants. So I wanna talk about where we stand. I've heard some vaccine experts recently say, like Paul Offit, for example, has said he doesn't expect a fourth surge due to this, but others are more cautious and take the flip side saying, "This is the calm before the storm. We're about to see another huge explosion." California has recently reported a new strain as accounts for maybe potentially 50% of cases now, and it could be 90% by the end of March. But we're seeing such big declines in the numbers in hospitalizations, in cases. So what should people make of these conflicting messages?

DR. CAPLAN: There's an attitude in medicine that many doctors take toward things like incipient or new prostate cancer, sometimes toward breast cancer, or at least lumps. It's called watchful waiting. You pay attention. You watch what's going on. But you don't do anything right away. I would still get vaccinated, I would still take what I could get. I still believe that it's likely that these vaccines are gonna provide some protection, if not against infection, then at least against the worst symptoms and the worst chances of dying because they're really gonna boost up the basic immune system, which should be able to start to fight against viruses.

That said, could we wind up with some virulent new strain that evades the current vaccine platforms? Yes. Is it likely? I don't think so. But what it does mean is get ready to get boosters because the response to new strains that have been a result of viral mutations is you gotta adjust your vaccine. That's what we'll do. I hope it doesn't send us back into quarantine and isolation and distancing and all the rest of it as our only control. I'm hoping that the manufacturers can roll out boosters more quickly than the first round of vaccines.

KIRA: And the FDA has just said that the vaccine developers will not need to start over with new clinical trials to these boosters. So that will greatly expedite the process. And do you think that's the right call?

DR. CAPLAN: Yes, absolutely. You're not changing the fundamental nature of the vaccine platform, you're just tweaking, if you will, which chemistry responds to the virus. So yeah, I do.

KIRA: And one question then that necessarily everyone is gonna wonder is, "Well, if I got the J&J vaccine, can I get an mRNA booster?" Can you mix and match? Is that gonna work for your immune system?

DR. CAPLAN: Yeah. We don't have any idea. And I wouldn't do that right away. I know some countries are thinking about that to get more, if you will, use out of a limited supply. I'd say wait three months and do it the right way, where the data is in evidence. I'm not worried about people getting a second shot of something different and dropping dead. I'm just worried that it won't work. [chuckle] So I'm not a fan of mix and match. You can do it in some studies, by the way. You could do it in some challenge studies and get a faster answer than you would having to try and do this in 30,000 people over a year. But no, I don't think that's a good way to go. And I'm not a big fan of one-shot strategies either. I think, what we know is that the second shot really kicks your immune system into high gear and that's what you want for real protection. So I know why people say it but I wouldn't advocate for it.

KIRA: Right. And for my last question. One of our big themes this year that we'll be following all throughout the year at leaps.org is our progress towards an eventual return to life and return to normalcy. So I have to ask that question to you. Given everything that you know and that we've discussed today, when do you think our lives and society will start to look normal again, with schools, and restaurants, and businesses open, people are flying and gathering without fear, traveling, etcetera?

DR. CAPLAN: I think you're gonna see a lot of that this summer. There's gonna be enough vaccine out there, even if the epidemiologists aren't 100% happy. As I said, I think a lot of people are gonna say, "I'm happy enough, good enough for me. I'm going to sports and I'm flying, and I'm taking a vacation." And we'll be outside again. Remember we had the ability to eat outdoors and congregate less when the weather's better around the whole country, and I think that will open up Europe and the US in addition. What I'm worried about is if we had to go back in the fall to a more controlled environment, either 'cause a new strain appeared, or just because things weren't as efficacious as we hoped they'd be. But I think summer is gonna be good this year.

KIRA: Well, I hope you're right. I hope your crystal ball is working today. [chuckle]

DR. CAPLAN: [chuckle] And if it's not working right, email Kira. Don't talk to me.

KIRA: Yeah, I cannot be held liable for this. Thank you Art for a fascinating discussion. And thanks to everyone for listening. If you like this show, follow Making Sense of Science to hear new episodes coming once a month. And if you wanna give us feedback, we'd love to hear from you. Get in touch on our website, leaps.org. And until next time, thanks everyone.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

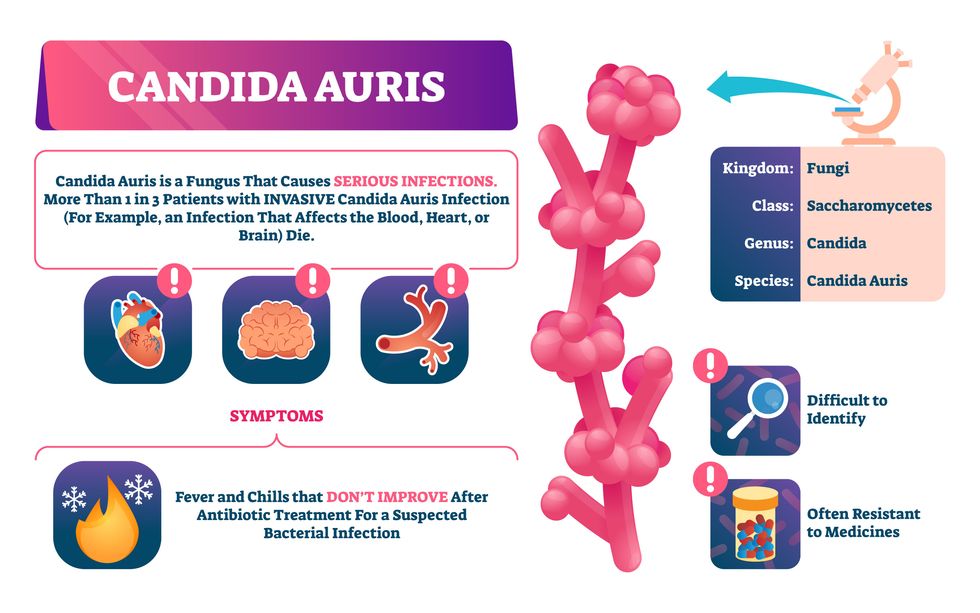

Doctors worry that fungal pathogens may cause the next pandemic.

Bacterial antibiotic resistance has been a concern in the medical field for several years. Now a new, similar threat is arising: drug-resistant fungal infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers antifungal and antimicrobial resistance to be among the world’s greatest public health challenges.

One particular type of fungal infection caused by Candida auris is escalating rapidly throughout the world. And to make matters worse, C. auris is becoming increasingly resistant to current antifungal medications, which means that if you develop a C. auris infection, the drugs your doctor prescribes may not work. “We’re effectively out of medicines,” says Thomas Walsh, founding director of the Center for Innovative Therapeutics and Diagnostics, a translational research center dedicated to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem. Walsh spoke about the challenges at a Demy-Colton Virtual Salon, one in a series of interactive discussions among life science thought leaders.

Although C. auris typically doesn’t sicken healthy people, it afflicts immunocompromised hospital patients and may cause severe infections that can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which the overwhelmed immune system begins to attack the body’s own organs. Between 30 and 60 percent of patients who contract a C. auris infection die from it, according to the CDC. People who are undergoing stem cell transplants, have catheters or have taken antifungal or antibiotic medicines are at highest risk. “We’re coming to a perfect storm of increasing resistance rates, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed patients worldwide and a bug that is adapting to higher temperatures as the climate changes,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the National BioDefense Science Board.

Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures.

Although medical professionals aren’t concerned at this point about C. auris evolving to affect healthy people, they worry that its presence in hospitals can turn routine surgeries into life-threatening calamities. “It’s coming,” says Fernandes. “It’s just a matter of time.”

An emerging global threat

“Fungi are found in the environment,” explains Fernandes, so Candida spores can easily wind up on people’s skin. In hospitals, they can be transferred from contact with healthcare workers or contaminated surfaces. Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures. It can enter the body during medical treatments that break the skin—and cause an infection. Overall, fungal infections cost some $48 billion in the U.S. each year. And infection rates are increasing because, in an ironic twist, advanced medical therapies are enabling severely ill patients to live longer and, therefore, be exposed to this pathogen.

The first-ever case of a C. auris infection was reported in Japan in 2009, although an analysis of Candida samples dated the earliest strain to a 1996 sample from South Korea. Since then, five separate varieties – called clades, which are similar to strains among bacteria – developed independently in different geographies: South Asia, East Asia, South Africa, South America and, recently, Iran. So far, C. auris infections have been reported in 35 countries.

In the U.S., the first infection was reported in 2016, and the CDC started tracking it nationally two years later. During that time, 5,654 cases have been reported to the CDC, which only tracks U.S. data.

What’s more notable than the number of cases is their rate of increase. In 2016, new cases increased by 175 percent and, on average, they have approximately doubled every year. From 2016 through 2022, the number of infections jumped from 63 to 2,377, a roughly 37-fold increase.

“This reminds me of what we saw with epidemics from 2013 through 2020… with Ebola, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Robin Robinson, CEO of Spriovas and founding director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These epidemics started with a hockey stick trajectory, Robinson says—a gradual growth leading to a sharp spike, just like the shape of a hockey stick.

Another challenge is that right now medics don’t have rapid diagnostic tests for fungal infections. Currently, patients are often misdiagnosed because C. auris resembles several other easily treated fungi. Or they are diagnosed long after the infection begins and is harder to treat.

The problem is that existing diagnostics tests can only identify C. auris once it reaches the bloodstream. Yet, because this pathogen infects bodily tissues first, it should be possible to catch it much earlier before it becomes life-threatening. “We have to diagnose it before it reaches the bloodstream,” Walsh says.

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics.

“We need to focus on rapid diagnostic tests that do not rely on a positive blood culture,” says John Sperzel, president and CEO of T2 Biosystems, a company specializing in diagnostics solutions. Blood cultures typically take two to three days for the concentration of Candida to become large enough to detect. The company’s novel test detects about 90 percent of Candida species within three to five hours—thanks to its ability to spot minute quantities of the pathogen in blood samples instead of waiting for them to incubate and proliferate.

Unlike other Candida species C. auris thrives at human body temperatures

Adobe Stock

Tackling the resistance challenge

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics. The number of cases that stopped responding to echinocandin, the first-line therapy for most Candida infections, tripled in 2020, according to a study by the CDC.

Now, each of the first four clades shows varying levels of resistance to all three commonly prescribed classes of antifungal medications, such as azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. For example, 97 percent of infections from C. auris Clade I are resistant to fluconazole, 54 percent to voriconazole and 30 percent of amphotericin. Nearly half are resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. Even with Clade II fungi, which has the least resistance of all the clades, 11 to 14 percent have become resistant to fluconazole.

Anti-fungal therapies typically target specific chemical compounds present on fungi’s cell membranes, but not on human cells—otherwise the medicine would cause damage to our own tissues. Fluconazole and other azole antifungals target a compound called ergosterol, preventing the fungal cells from replicating. Over the years, however, C. auris evolved to resist it, so existing fungal medications don’t work as well anymore.

A newer class of drugs called echinocandins targets a different part of the fungal cell. “The echinocandins – like caspofungin – inhibit (a part of the fungi) involved in making glucan, which is an essential component of the fungal cell wall and is not found in human cells,” Fernandes says. New antifungal treatments are needed, she adds, but there are only a few magic bullets that will hit just the fungus and not the human cells.

Research to fight infections also has been challenged by a lack of government support. That is changing now that BARDA is requesting proposals to develop novel antifungals. “The scope includes C. auris, as well as antifungals following a radiological/nuclear emergency, says BARDA spokesperson Elleen Kane.

The remaining challenge is the number of patients available to participate in clinical trials. Large numbers are needed, but the available patients are quite sick and often die before trials can be completed. Consequently, few biopharmaceutical companies are developing new treatments for C. auris.

ClinicalTrials.gov reports only two drugs in development for invasive C. auris infections—those than can spread throughout the body rather than localize in one particular area, like throat or vaginal infections: ibrexafungerp by Scynexis, Inc., fosmanogepix, by Pfizer.

Scynexis’ ibrexafungerp appears active against C. auris and other emerging, drug-resistant pathogens. The FDA recently approved it as a therapy for vaginal yeast infections and it is undergoing Phase III clinical trials against invasive candidiasis in an attempt to keep the infection from spreading.

“Ibreafungerp is structurally different from other echinocandins,” Fernandes says, because it targets a different part of the fungus. “We’re lucky it has activity against C. auris.”

Pfizer’s fosmanogepix is in Phase II clinical trials for patients with invasive fungal infections caused by multiple Candida species. Results are showing significantly better survival rates for people taking fosmanogepix.

Although C. auris does pose a serious threat to healthcare worldwide, scientists try to stay optimistic—because they recognized the problem early enough, they might have solutions in place before the perfect storm hits. “There is a bit of hope,” says Robinson. “BARDA has finally been able to fund the development of new antifungal agents and, hopefully, this year we can get several new classes of antifungals into development.”

New elevators could lift up our access to space

A space elevator would be cheaper and cleaner than using rockets

Story by Big Think

When people first started exploring space in the 1960s, it cost upwards of $80,000 (adjusted for inflation) to put a single pound of payload into low-Earth orbit.

A major reason for this high cost was the need to build a new, expensive rocket for every launch. That really started to change when SpaceX began making cheap, reusable rockets, and today, the company is ferrying customer payloads to LEO at a price of just $1,300 per pound.

This is making space accessible to scientists, startups, and tourists who never could have afforded it previously, but the cheapest way to reach orbit might not be a rocket at all — it could be an elevator.

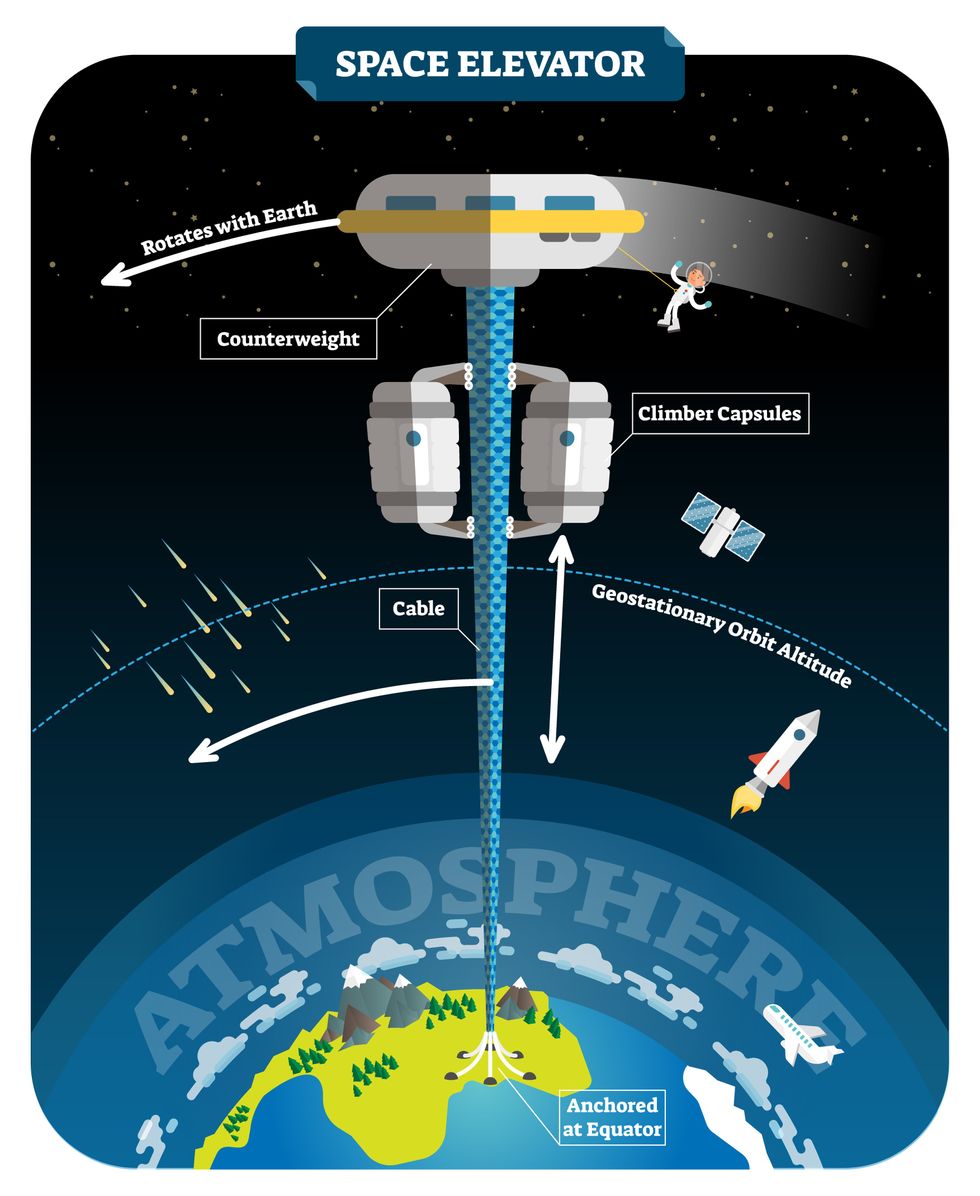

The space elevator

The seeds for a space elevator were first planted by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1895, who, after visiting the 1,000-foot (305 m) Eiffel Tower, published a paper theorizing about the construction of a structure 22,000 miles (35,400 km) high.

This would provide access to geostationary orbit, an altitude where objects appear to remain fixed above Earth’s surface, but Tsiolkovsky conceded that no material could support the weight of such a tower.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

In 1959, soon after Sputnik, Russian engineer Yuri N. Artsutanov proposed a way around this issue: instead of building a space elevator from the ground up, start at the top. More specifically, he suggested placing a satellite in geostationary orbit and dropping a tether from it down to Earth’s equator. As the tether descended, the satellite would ascend. Once attached to Earth’s surface, the tether would be kept taut, thanks to a combination of gravitational and centrifugal forces.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit. According to physicist Bradley Edwards, who researched the concept for NASA about 20 years ago, it’d cost $10 billion and take 15 years to build a space elevator, but once operational, the cost of sending a payload to any Earth orbit could be as low as $100 per pound.

“Once you reduce the cost to almost a Fed-Ex kind of level, it opens the doors to lots of people, lots of countries, and lots of companies to get involved in space,” Edwards told Space.com in 2005.

In addition to the economic advantages, a space elevator would also be cleaner than using rockets — there’d be no burning of fuel, no harmful greenhouse emissions — and the new transport system wouldn’t contribute to the problem of space junk to the same degree that expendable rockets do.

So, why don’t we have one yet?

Tether troubles

Edwards wrote in his report for NASA that all of the technology needed to build a space elevator already existed except the material needed to build the tether, which needs to be light but also strong enough to withstand all the huge forces acting upon it.

The good news, according to the report, was that the perfect material — ultra-strong, ultra-tiny “nanotubes” of carbon — would be available in just two years.

“[S]teel is not strong enough, neither is Kevlar, carbon fiber, spider silk, or any other material other than carbon nanotubes,” wrote Edwards. “Fortunately for us, carbon nanotube research is extremely hot right now, and it is progressing quickly to commercial production.”Unfortunately, he misjudged how hard it would be to synthesize carbon nanotubes — to date, no one has been able to grow one longer than 21 inches (53 cm).

Further research into the material revealed that it tends to fray under extreme stress, too, meaning even if we could manufacture carbon nanotubes at the lengths needed, they’d be at risk of snapping, not only destroying the space elevator, but threatening lives on Earth.

Looking ahead

Carbon nanotubes might have been the early frontrunner as the tether material for space elevators, but there are other options, including graphene, an essentially two-dimensional form of carbon that is already easier to scale up than nanotubes (though still not easy).

Contrary to Edwards’ report, Johns Hopkins University researchers Sean Sun and Dan Popescu say Kevlar fibers could work — we would just need to constantly repair the tether, the same way the human body constantly repairs its tendons.

“Using sensors and artificially intelligent software, it would be possible to model the whole tether mathematically so as to predict when, where, and how the fibers would break,” the researchers wrote in Aeon in 2018.

“When they did, speedy robotic climbers patrolling up and down the tether would replace them, adjusting the rate of maintenance and repair as needed — mimicking the sensitivity of biological processes,” they continued.Astronomers from the University of Cambridge and Columbia University also think Kevlar could work for a space elevator — if we built it from the moon, rather than Earth.

They call their concept the Spaceline, and the idea is that a tether attached to the moon’s surface could extend toward Earth’s geostationary orbit, held taut by the pull of our planet’s gravity. We could then use rockets to deliver payloads — and potentially people — to solar-powered climber robots positioned at the end of this 200,000+ mile long tether. The bots could then travel up the line to the moon’s surface.

This wouldn’t eliminate the need for rockets to get into Earth’s orbit, but it would be a cheaper way to get to the moon. The forces acting on a lunar space elevator wouldn’t be as strong as one extending from Earth’s surface, either, according to the researchers, opening up more options for tether materials.

“[T]he necessary strength of the material is much lower than an Earth-based elevator — and thus it could be built from fibers that are already mass-produced … and relatively affordable,” they wrote in a paper shared on the preprint server arXiv.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one.

Electrically powered climber capsules could go up down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

Adobe Stock

Some Chinese researchers, meanwhile, aren’t giving up on the idea of using carbon nanotubes for a space elevator — in 2018, a team from Tsinghua University revealed that they’d developed nanotubes that they say are strong enough for a tether.

The researchers are still working on the issue of scaling up production, but in 2021, state-owned news outlet Xinhua released a video depicting an in-development concept, called “Sky Ladder,” that would consist of space elevators above Earth and the moon.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one. If the project could be pulled off — a huge if — China predicts Sky Ladder could cut the cost of sending people and goods to the moon by 96 percent.

The bottom line

In the 120 years since Tsiolkovsky looked at the Eiffel Tower and thought way bigger, tremendous progress has been made developing materials with the properties needed for a space elevator. At this point, it seems likely we could one day have a material that can be manufactured at the scale needed for a tether — but by the time that happens, the need for a space elevator may have evaporated.

Several aerospace companies are making progress with their own reusable rockets, and as those join the market with SpaceX, competition could cause launch prices to fall further.

California startup SpinLaunch, meanwhile, is developing a massive centrifuge to fling payloads into space, where much smaller rockets can propel them into orbit. If the company succeeds (another one of those big ifs), it says the system would slash the amount of fuel needed to reach orbit by 70 percent.

Even if SpinLaunch doesn’t get off the ground, several groups are developing environmentally friendly rocket fuels that produce far fewer (or no) harmful emissions. More work is needed to efficiently scale up their production, but overcoming that hurdle will likely be far easier than building a 22,000-mile (35,400-km) elevator to space.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.