New Tests Measure Your Body’s Biological Age, Offering a Glimpse into the Future of Health Care

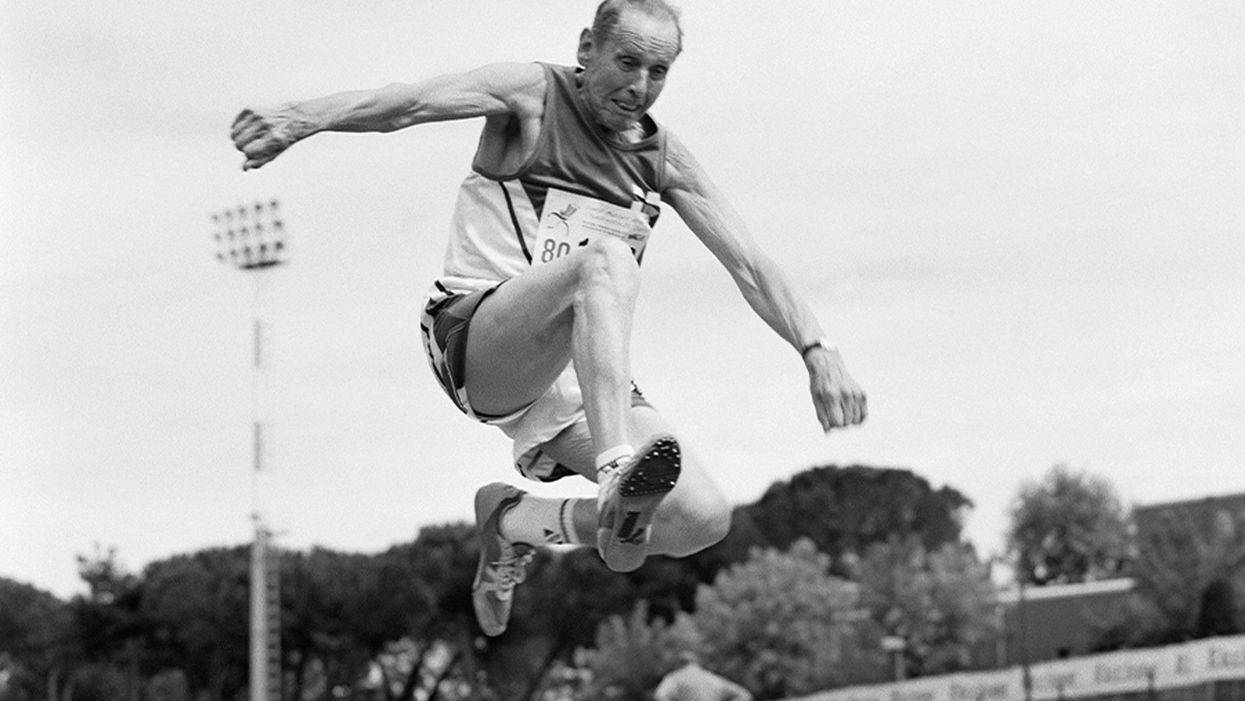

A senior long jumper competes in the 80-84-year-old age division at the 2007 World Masters Championships Stadia (track and field competition) at Riccione Stadium in Riccione, Italy on September 6, 2007. From the book project Racing Age.

What if a simple blood test revealed how fast you're aging, and this meant more to you and your insurance company than the number of candles on your birthday cake?

The question of why individuals thrive or decline has loomed large in 2020, with COVID-19 harming people of all ages, while leaving others asymptomatic. Meanwhile, scientists have produced new measures, called aging clocks, that attempt to predict mortality and may eventually affect how we perceive aging.

Take, for example, "senior" athletes who perform more like 50-year-olds. But people over 65 are lumped into one category, whether they are winning marathons or using a walker. Meanwhile, I'm entering "middle age," a label just as vague. It's frustrating to have a better grasp on the lifecycle of my phone than my own body.

That could change soon, due to clock technology. In 2013, UCLA biostatistician Steven Horvath took a new approach to an old carnival trick, guessing people's ages by looking at epigenetics: how chemical compounds in our cells turn genetic instructions on or off. Exercise, pollutants, and other aspects of lifestyle and environment can flip these switches, converting a skin cell into a hair cell, for example. Then, hair may sprout from your ears.

Horvath's epigenetic clock approximated age within just a few years; an above-average estimate suggested fast aging. This "basically changed everything," said Vadim Gladyshev, a Harvard geneticist, leading to more epigenetic clocks and, just since May, additional clocks of the heart, products of cell metabolism, and microbes in a person's mouth and gut.

Machine learning is fueling these discoveries. Scientists send algorithms hunting through jungles of health data for factors related to physical demise. "Nothing in [the aging] industry has progressed as much as biomarkers," said Alex Zhavoronkov, CEO of Deep Longevity, a pioneer in learning-based clocks.

Researchers told LeapsMag that this tech could help identify age-related vulnerabilities to diseases—including COVID-19—and protective drugs.

Clocking disease vulnerability

In July, Yale researcher Morgan Levine found people were more likely to be hospitalized and die from COVID-19 if their aging clocks were ticking ahead of their calendar years. This effect held regardless of pre-existing conditions.

The study used Levine's biological aging clock, called PhenoAge, which is more accurate than previous versions. To develop it, she looked at data on health indices over several decades, focusing on nine hallmarks of aging—such as inflammation—that correspond to when people die. Then she used AI to find which epigenetic patterns in blood samples were strongly associated with physical aging. The PhenoAge clock reads these patterns to predict biological age; mortality goes up 62 percent among the fastest agers.

The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention.

Because PhenoAge links chronic inflammation to aging and vulnerability, Levine proposed treating "inflammaging" to counter COVID-19.

Gladyshev reported similar findings, and Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute of Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, agreed that biological age deserves greater focus. PhenoAge is an important innovation, he said, but most precise when measuring average age across large populations. Until clocks—including his blood protein version—account for differences in how individuals age, "Multi-morbidity is really the major biomarker" for a given person. Barzilai thinks individuals over 65 with two or more diseases are biologically older than their chronological age—about half the population in this study.

He believes COVID-19 efforts aren't taking stock of these differences. "The scientists are living in silos," he said, with many unaware aging has a biology that can be targeted.

The missed opportunities could be profound, especially for lower-income communities with disproportionately advanced aging. Barzilai has read eight different observational studies finding decreased COVID-19 severity among people taking metformin, the diabetes drug, which is believed to slow down the major hallmarks of biological aging, such as inflammation. Once a vaccine is identified, biologically older people could supplement it with metformin, but the medical establishment requires lengthy clinical trials. "The conservatism is taking over in days of war," Barzilai said.

Drug benefits on time

Clocks, once validated, could gauge drug effectiveness against age-related diseases quicker and cheaper than trials that track health outcomes over many years, expediting FDA approval of such therapies. For this to happen, though, the FDA must see evidence that rewinding clocks or improving related biomarkers leads to clinical benefits for patients. Researchers believe that clinical applications for at least some of these clocks are five to 10 years away.

Progress was made in last year's TRIIM trial, run by immunologist Gregory Fahy at Stanford Medical Center. People in their 50s took growth hormone, metformin and another diabetes drug, dehydroepiandrosterone, for 12 months. The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention. Don't quit your gym just yet; TRIIM included just nine Caucasian men. A follow-up with 85 diverse participants begins next month.

But even group averages of epigenetic measures can be questionable, explained Willard Freeman, a researcher with the Reynolds Oklahoma Center on Aging. Consider this odd finding: heroin addicts tend to have younger epigenetic ages. "With the exception of Keith Richards, I don't think heroin is a great way to live a long healthy life," Freeman said.

Such confounders reveal that scientists—and AI—are still struggling to unearth the roots of aging. Do clocks simply reflect damage, mirrors to show who's the frailest of them all? Or do they programmatically drive aging? The answer involves vast complexity, like trying to deduce the direct causes of a 17-car pileup on a potholed road in foggy conditions. Except, instead of 17 cars, it's millions of epigenetic sites and thousands of potential genes, RNA molecules and blood proteins acting on aging and each other.

Because the various measures—epigenetics, microbes, etc.—capture distinct aging dimensions, an important goal is unifying them into one "mosaic of biological ages," as Levine called it. Gladyshev said more datasets are needed. Just yesterday, though, Zhavoronkov launched Deep Longevity's groundbreaking composite of metrics to consumers – something that was previously available only to clinicians. The iPhone app allows users to upload their own samples and tracks aging on multiple levels – epigenetic, behavioral, microbiome, and more. It even includes a deep psychological clock asking if people feel as old as they are. Perhaps Twain's adage about mind over matter is evidence-backed.

Zhavoronkov appeared youthful in our Zoom interview, but admitted self-testing shows an advanced age because "I do not sleep"; indeed, he'd scheduled me at midnight Hong Kong time. Perhaps explaining his insomnia, he fears economic collapse if age-related diseases cost the global economy over $30 trillion by 2030. Rather than seeking eternal life, researchers like Zhavoronkov aim to increase health span: fully living our final decades without excess pain and hospital bills.

It's also a lucrative sales pitch to 7.8 billion aging humans.

Get your bio age

Levine, the Yale scientist, has partnered with Elysium Health to sell Index, an epigenetic measure launched in late 2019, direct to consumers, using their saliva samples. Elysium will roll out additional measures as research progresses, starting with an assessment of how fast someone is accumulating cells that no longer divide. "The more measures to capture specific processes, the more we can actually understand what's unique for an individual," Levine said.

Another company, InsideTracker, with an advisory board headlined by Harvard's David Sinclair, eschews the quirkiness of epigenetics. Its new InnerAge 2.0 test, announced this month, analyzes 18 blood biomarkers associated with longevity.

"You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them."

Because aging isn't considered a disease, consumer aging tests don't require FDA approval, and some researchers are skeptical of their use in the near future. "I'm on the fence as to whether these things are ready to be rolled out," said Freeman, the Oklahoma researcher. "We need to do our traditional experimental study design to [be] confident they're actually useful."

Then, 50-year-olds who are biologically 45 may wait five years for their first colonoscopy, Barzilai said. Despite some forerunners, clinical applications for individuals are mostly prospective, yet I was intrigued. Could these clocks reveal if I'm following the footsteps of the super-agers? Or will I rack up the hospital bills of Zhavoronkov's nightmares?

I sent my blood for testing with InsideTracker. Fearing the worst—an InnerAge accelerated by a couple of decades—I asked thought leaders where this technology is headed.

Insurance 2030

With continued advances, by 2030 you'll learn your biological age with a glance at your wristwatch. You won't be the only monitor; your insurance company may send an alert if your age goes too high, threatening lost rewards.

If this seems implausible, consider that life insurer John Hancock already tracks a VitalityAge. With Obamacare incentivizing companies to engage policyholders in improving health, many are dangling rewards for fitness. BlueCross BlueShield covers 25 percent of InsideTracker's cost, and UnitedHealthcare offers a suite of such programs, including "missions" for policyholders to lower their Rally age. "People underestimate the amount of time they're sedentary," said Michael Bess, vice president of healthcare strategies. "So having this technology to drive positive reinforcement is just another way to encourage healthy behavior."

It's unclear if these programs will close health gaps, or simply attract customers already prioritizing fitness. And insurers could raise your premium if you don't measure up. Obamacare forbids discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, but will accelerated age qualify for this protection?

Liz McFall, a sociologist at the University of Edinburgh, thinks the answer depends on whether we view aging as controllable. "You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them," she said.

That outcome troubles Mark Rothstein, director of the Institute of Bioethics at the University of Louisville. "For those living with air pollution and unsafe water, in food deserts and where you can't safely exercise, then [insurers] take the results in terms of biological stressors, now you're adding insult to injury," he said.

Government could subsidize aging clocks and interventions for older people with fewer resources for controlling their health—and the greatest room for improving their epigenetic age. Rothstein supports that policy, but said, "I don't see it happening."

Bio age working for you

2030 again. A job posting seeks a "go-getter," so you attach a doctor's note to your resume proving you're ten years younger than your chronological age.

This prospect intrigued Cathy Ventrell-Monsees, senior advisor at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Any marker other than age is a step forward," she said. "Age simply doesn't determine any kind of cognitive or physical ability."

What if the assessment isn't voluntary? Armed with AI, future employers could surveil a candidate's biological age from their head-shot. Haut.ai is already marketing an uncannily accurate PhotoAgeClock. Its CEO, Anastasia Georgievskaya, noted this tech's promise in other contexts; it could help people literally see the connection between healthier lifestyles and looking young and attractive. "The images keep people quite engaged," she told me.

Updating laws could minimize drawbacks. Employers are already prohibited from using genetic information to discriminate (think 23andMe). The ban could be extended to epigenetics. "I would imagine biomarkers for aging go a similar path as genetic nondiscrimination," said McFall, the sociologist.

Will we use aging clocks to screen candidates for the highest office? Barzilai, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine researcher, believes Trump and Biden have similar biological ages. But one of Barzilai's factors, BMI, is warped by Trump miraculously getting taller. "Usually people get shorter with age," Barzilai said. "His weight has been increasing, but his BMI stays the same."

As for my bio age? InnerAge suggested I'm four years younger—and by boosting my iron levels, the program suggests, I could be younger still.

We need standards for these tests, and customers must understand their shortcomings. With such transparency, though, the benefits could be compelling. In March, Theresa Brown, a 44-year-old from Kansas, learned her InnerAge was 57.2. She followed InsideTracker's recommendations, including regular intermittent fasting. Retested five months later, her age had dropped to 34.1. "It's not that I guaranteed another 10 or 20 years to my life. It's that it encourages me. Whether I really am or not, I just feel younger. I'll take that."

Which leads back to Zhavoronkov's psychological clock. Perhaps lowering our InnerAges can be the self-fulfilling prophesy that helps Theresa and me age like the super-athletes who thrive longer than expected. McFall noted the power of simple, sufficiently credible goals for encouraging better health. Think 10,000 steps per day, she said.

Want to be 34 again? Just do it.

Yet, many people's budgets just don't allow gym memberships, nutritious groceries, or futuristic aging clocks. Bill Gates cautioned we overestimate progress in the next two years, while underestimating the next ten. Policies should ensure that age testing and interventions are distributed fairly.

"Within the next 5 to 10 years," said Gladyshev, "there will be drugs and lifestyle changes which could actually increase lifespan or healthspan for the entire population."

After spaceflight record, NASA looks to protect astronauts on even longer trips

NASA astronaut Frank Rubio floats by the International Space Station’s “window to the world.” Yesterday, he returned from the longest single spaceflight by a U.S. astronaut on record - over one year. Exploring deep space will require even longer missions.

At T-minus six seconds, the main engines of the Atlantis Space Shuttle ignited, rattling its capsule “like a skyscraper in an earthquake,” according to astronaut Tom Jones, describing the 1988 launch. As the rocket lifted off and accelerated to three times the force of Earth's gravity, “It felt as if two of my friends were standing on my chest and wouldn’t get off.” But when Atlantis reached orbit, the main engines cut off, and the astronauts were suddenly weightless.

Since 1961, NASA has sent hundreds of astronauts into space while working to making their voyages safer and smoother. Yet, challenges remain. Weightlessness may look amusing when watched from Earth, but it has myriad effects on cognition, movement and other functions. When missions to space stretch to six months or longer, microgravity can impact astronauts’ health and performance, making it more difficult to operate their spacecraft.

Yesterday, NASA astronaut Frank Rubio returned to Earth after over one year, the longest single spaceflight for a U.S. astronaut. But this is just the start; longer and more complex missions into deep space loom ahead, from returning to the moon in 2025 to eventually sending humans to Mars. To ensure that these missions succeed, NASA is increasing efforts to study the biological effects and prevent harm.

The dangers of microgravity are real

A NASA report published in 2016 details a long list of incidents and near-misses caused – at least partly – by space-induced changes in astronauts’ vision and coordination. These issues make it harder to move with precision and to judge distance and velocity.

According to the report, in 1997, a resupply ship collided with the Mir space station, possibly because a crew member bumped into the commander during the final docking maneuver. This mishap caused significant damage to the space station.

Returns to Earth suffered from problems, too. The same report notes that touchdown speeds during the first 100 space shuttle landings were “outside acceptable limits. The fastest landing on record – 224 knots (258 miles) per hour – was linked to the commander’s momentary spatial disorientation.” Earlier, each of the six Apollo crews that landed on the moon had difficulty recognizing moon landmarks and estimating distances. For example, Apollo 15 landed in an unplanned area, ultimately straddling the rim of a five-foot deep crater on the moon, harming one of its engines.

Spaceflight causes unique stresses on astronauts’ brains and central nervous systems. NASA is working to reduce these harmful effects.

NASA

Space messes up your brain

In space, astronauts face the challenges of microgravity, ionizing radiation, social isolation, high workloads, altered circadian rhythms, monotony, confined living quarters and a high-risk environment. Among these issues, microgravity is one of the most consequential in terms of physiological changes. It changes the brain’s structure and its functioning, which can hurt astronauts’ performance.

The brain shifts upwards within the skull, displacing the cerebrospinal fluid, which reduces the brain’s cushioning. Essentially, the brain becomes crowded inside the skull like a pair of too-tight shoes.

That’s partly because of how being in space alters blood flow. On Earth, gravity pulls our blood and other internal fluids toward our feet, but our circulatory valves ensure that the fluids are evenly distributed throughout the body. In space, there’s not enough gravity to pull the fluids down, and they shift up, says Rachael D. Seidler, a physiologist specializing in spaceflight at the University of Florida and principal investigator on many space-related studies. The head swells and legs appear thinner, causing what astronauts call “puffy face chicken legs.”

“The brain changes at the structural and functional level,” says Steven Jillings, equilibrium and aerospace researcher at the University of Antwerp in Belgium. “The brain shifts upwards within the skull,” displacing the cerebrospinal fluid, which reduces the brain’s cushioning. Essentially, the brain becomes crowded inside the skull like a pair of too-tight shoes. Some of the displaced cerebrospinal fluid goes into cavities within the brain, called ventricles, enlarging them. “The remaining fluids pool near the chest and heart,” explains Jillings. After 12 consecutive months in space, one astronaut had a ventricle that was 25 percent larger than before the mission.

Some changes reverse themselves while others persist for a while. An example of a longer-lasting problem is spaceflight-induced neuro-ocular syndrome, which results in near-sightedness and pressure inside the skull. A study of approximately 300 astronauts shows near-sightedness affects about 60 percent of astronauts after long missions on the International Space Station (ISS) and more than 25 percent after spaceflights of only a few weeks.

Another long-term change could be the decreased ability of cerebrospinal fluid to clear waste products from the brain, Seidler says. That’s because compressing the brain also compresses its waste-removing glymphatic pathways, resulting in inflammation, vulnerability to injuries and worsening its overall health.

The effects of long space missions were best demonstrated on astronaut twins Scott and Mark Kelly. This NASA Twins Study showed multiple, perhaps permanent, changes in Scott after his 340-day mission aboard the ISS, compared to Mark, who remained on Earth. The differences included declines in Scott’s speed, accuracy and cognitive abilities that persisted longer than six months after returning to Earth in March 2016.

By the end of 2020, Scott’s cognitive abilities improved, but structural and physiological changes to his eyes still remained, he said in a BBC interview.

“It seems clear that the upward shift of the brain and compression of the surrounding tissues with ventricular expansion might not be a good thing,” Seidler says. “But, at this point, the long-term consequences to brain health and human performance are not really known.”

NASA astronaut Kate Rubins conducts a session for the Neuromapping investigation.

NASA

Staying sharp in space

To investigate how prolonged space travel affects the brain, NASA launched a new initiative called the Complement of Integrated Protocols for Human Exploration Research (CIPHER). “CIPHER investigates how long-duration spaceflight affects both brain structure and function,” says neurobehavioral scientist Mathias Basner at the University of Pennsylvania, a principal investigator for several NASA studies. “Through it, we can find out how the brain adapts to the spaceflight environment and how certain brain regions (behave) differently after – relative to before – the mission.”

To do this, he says, “Astronauts will perform NASA’s cognition test battery before, during and after six- to 12-month missions, and will also perform the same test battery in an MRI scanner before and after the mission. We have to make sure we better understand the functional consequences of spaceflight on the human brain before we can send humans safely to the moon and, especially, to Mars.”

As we go deeper into space, astronauts cognitive and physical functions will be even more important. “A trip to Mars will take about one year…and will introduce long communication delays,” Seidler says. “If you are on that mission and have a problem, it may take eight to 10 minutes for your message to reach mission control, and another eight to 10 minutes for the response to get back to you.” In an emergency situation, that may be too late for the response to matter.

“On a mission to Mars, astronauts will be exposed to stressors for unprecedented amounts of time,” Basner says. To counter them, NASA is considering the continuous use of artificial gravity during the journey, and Seidler is studying whether artificial gravity can reduce the harmful effects of microgravity. Some scientists are looking at precision brain stimulation as a way to improve memory and reduce anxiety due to prolonged exposure to radiation in space.

Other scientists are exploring how to protect neural stem cells (which create brain cells) from radiation damage, developing drugs to repair damaged brain cells and protect cells from radiation.

To boldly go where no astronauts have gone before, they must have optimal reflexes, vision and decision-making. In the era of deep space exploration, the brain—without a doubt—is the final frontier.

Additionally, NASA is scrutinizing each aspect of the mission, including astronaut exercise, nutrition and intellectual engagement. “We need to give astronauts meaningful work. We need to stimulate their sensory, cognitive and other systems appropriately,” Basner says, especially given their extreme confinement and isolation. The scientific experiments performed on the ISS – like studying how microgravity affects the ability of tissue to regenerate is a good example.

“We need to keep them engaged socially, too,” he continues. The ISS crew, for example, regularly broadcasts from space and answers prerecorded questions from students on Earth, and can engage with social media in real time. And, despite tight quarters, NASA is ensuring the crew capsule and living quarters on the moon or Mars include private space, which is critical for good mental health.

Exploring deep space builds on a foundation that began when astronauts first left the planet. With each mission, scientists learn more about spaceflight effects on astronauts’ bodies. NASA will be using these lessons to succeed with its plans to build science stations on the moon and, eventually, Mars.

“Through internally and externally led research, investigations implemented in space and in spaceflight simulations on Earth, we are striving to reduce the likelihood and potential impacts of neurostructural changes in future, extended spaceflight,” summarizes NASA scientist Alexandra Whitmire. To boldly go where no astronauts have gone before, they must have optimal reflexes, vision and decision-making. In the era of deep space exploration, the brain—without a doubt—is the final frontier.

A newly discovered brain cell may lead to better treatments for cognitive disorders

Swiss researchers have found a type of brain cell that appears to be a hybrid of the two other main types — and it could lead to new treatments for brain disorders.

Swiss researchers have discovered a third type of brain cell that appears to be a hybrid of the two other primary types — and it could lead to new treatments for many brain disorders.

The challenge: Most of the cells in the brain are either neurons or glial cells. While neurons use electrical and chemical signals to send messages to one another across small gaps called synapses, glial cells exist to support and protect neurons.

Astrocytes are a type of glial cell found near synapses. This close proximity to the place where brain signals are sent and received has led researchers to suspect that astrocytes might play an active role in the transmission of information inside the brain — a.k.a. “neurotransmission” — but no one has been able to prove the theory.

A new brain cell: Researchers at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering and the University of Lausanne believe they’ve definitively proven that some astrocytes do actively participate in neurotransmission, making them a sort of hybrid of neurons and glial cells.

According to the researchers, this third type of brain cell, which they call a “glutamatergic astrocyte,” could offer a way to treat Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other disorders of the nervous system.

“Its discovery opens up immense research prospects,” said study co-director Andrea Volterra.

The study: Neurotransmission starts with a neuron releasing a chemical called a neurotransmitter, so the first thing the researchers did in their study was look at whether astrocytes can release the main neurotransmitter used by neurons: glutamate.

By analyzing astrocytes taken from the brains of mice, they discovered that certain astrocytes in the brain’s hippocampus did include the “molecular machinery” needed to excrete glutamate. They found evidence of the same machinery when they looked at datasets of human glial cells.

Finally, to demonstrate that these hybrid cells are actually playing a role in brain signaling, the researchers suppressed their ability to secrete glutamate in the brains of mice. This caused the rodents to experience memory problems.

“Our next studies will explore the potential protective role of this type of cell against memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as its role in other regions and pathologies than those explored here,” said Andrea Volterra, University of Lausanne.

But why? The researchers aren’t sure why the brain needs glutamatergic astrocytes when it already has neurons, but Volterra suspects the hybrid brain cells may help with the distribution of signals — a single astrocyte can be in contact with thousands of synapses.

“Often, we have neuronal information that needs to spread to larger ensembles, and neurons are not very good for the coordination of this,” researcher Ludovic Telley told New Scientist.

Looking ahead: More research is needed to see how the new brain cell functions in people, but the discovery that it plays a role in memory in mice suggests it might be a worthwhile target for Alzheimer’s disease treatments.

The researchers also found evidence during their study that the cell might play a role in brain circuits linked to seizures and voluntary movements, meaning it’s also a new lead in the hunt for better epilepsy and Parkinson’s treatments.

“Our next studies will explore the potential protective role of this type of cell against memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as its role in other regions and pathologies than those explored here,” said Volterra.