New Tests Measure Your Body’s Biological Age, Offering a Glimpse into the Future of Health Care

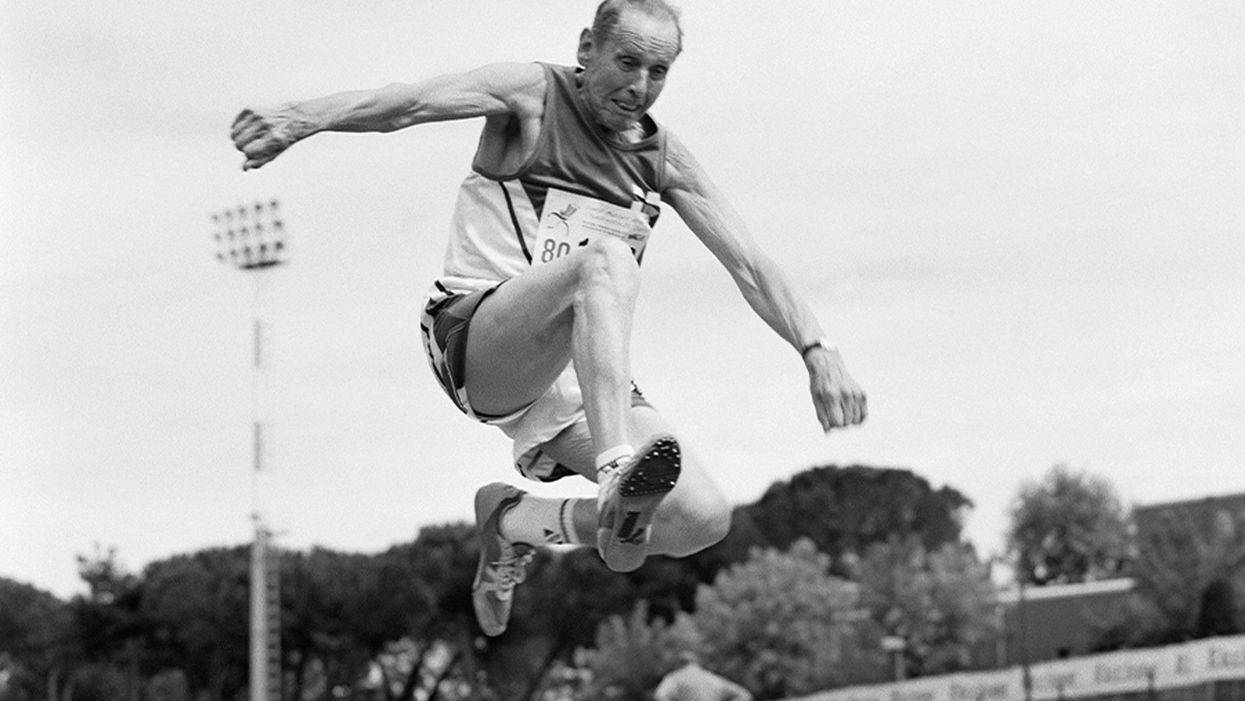

A senior long jumper competes in the 80-84-year-old age division at the 2007 World Masters Championships Stadia (track and field competition) at Riccione Stadium in Riccione, Italy on September 6, 2007. From the book project Racing Age.

What if a simple blood test revealed how fast you're aging, and this meant more to you and your insurance company than the number of candles on your birthday cake?

The question of why individuals thrive or decline has loomed large in 2020, with COVID-19 harming people of all ages, while leaving others asymptomatic. Meanwhile, scientists have produced new measures, called aging clocks, that attempt to predict mortality and may eventually affect how we perceive aging.

Take, for example, "senior" athletes who perform more like 50-year-olds. But people over 65 are lumped into one category, whether they are winning marathons or using a walker. Meanwhile, I'm entering "middle age," a label just as vague. It's frustrating to have a better grasp on the lifecycle of my phone than my own body.

That could change soon, due to clock technology. In 2013, UCLA biostatistician Steven Horvath took a new approach to an old carnival trick, guessing people's ages by looking at epigenetics: how chemical compounds in our cells turn genetic instructions on or off. Exercise, pollutants, and other aspects of lifestyle and environment can flip these switches, converting a skin cell into a hair cell, for example. Then, hair may sprout from your ears.

Horvath's epigenetic clock approximated age within just a few years; an above-average estimate suggested fast aging. This "basically changed everything," said Vadim Gladyshev, a Harvard geneticist, leading to more epigenetic clocks and, just since May, additional clocks of the heart, products of cell metabolism, and microbes in a person's mouth and gut.

Machine learning is fueling these discoveries. Scientists send algorithms hunting through jungles of health data for factors related to physical demise. "Nothing in [the aging] industry has progressed as much as biomarkers," said Alex Zhavoronkov, CEO of Deep Longevity, a pioneer in learning-based clocks.

Researchers told LeapsMag that this tech could help identify age-related vulnerabilities to diseases—including COVID-19—and protective drugs.

Clocking disease vulnerability

In July, Yale researcher Morgan Levine found people were more likely to be hospitalized and die from COVID-19 if their aging clocks were ticking ahead of their calendar years. This effect held regardless of pre-existing conditions.

The study used Levine's biological aging clock, called PhenoAge, which is more accurate than previous versions. To develop it, she looked at data on health indices over several decades, focusing on nine hallmarks of aging—such as inflammation—that correspond to when people die. Then she used AI to find which epigenetic patterns in blood samples were strongly associated with physical aging. The PhenoAge clock reads these patterns to predict biological age; mortality goes up 62 percent among the fastest agers.

The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention.

Because PhenoAge links chronic inflammation to aging and vulnerability, Levine proposed treating "inflammaging" to counter COVID-19.

Gladyshev reported similar findings, and Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute of Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, agreed that biological age deserves greater focus. PhenoAge is an important innovation, he said, but most precise when measuring average age across large populations. Until clocks—including his blood protein version—account for differences in how individuals age, "Multi-morbidity is really the major biomarker" for a given person. Barzilai thinks individuals over 65 with two or more diseases are biologically older than their chronological age—about half the population in this study.

He believes COVID-19 efforts aren't taking stock of these differences. "The scientists are living in silos," he said, with many unaware aging has a biology that can be targeted.

The missed opportunities could be profound, especially for lower-income communities with disproportionately advanced aging. Barzilai has read eight different observational studies finding decreased COVID-19 severity among people taking metformin, the diabetes drug, which is believed to slow down the major hallmarks of biological aging, such as inflammation. Once a vaccine is identified, biologically older people could supplement it with metformin, but the medical establishment requires lengthy clinical trials. "The conservatism is taking over in days of war," Barzilai said.

Drug benefits on time

Clocks, once validated, could gauge drug effectiveness against age-related diseases quicker and cheaper than trials that track health outcomes over many years, expediting FDA approval of such therapies. For this to happen, though, the FDA must see evidence that rewinding clocks or improving related biomarkers leads to clinical benefits for patients. Researchers believe that clinical applications for at least some of these clocks are five to 10 years away.

Progress was made in last year's TRIIM trial, run by immunologist Gregory Fahy at Stanford Medical Center. People in their 50s took growth hormone, metformin and another diabetes drug, dehydroepiandrosterone, for 12 months. The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention. Don't quit your gym just yet; TRIIM included just nine Caucasian men. A follow-up with 85 diverse participants begins next month.

But even group averages of epigenetic measures can be questionable, explained Willard Freeman, a researcher with the Reynolds Oklahoma Center on Aging. Consider this odd finding: heroin addicts tend to have younger epigenetic ages. "With the exception of Keith Richards, I don't think heroin is a great way to live a long healthy life," Freeman said.

Such confounders reveal that scientists—and AI—are still struggling to unearth the roots of aging. Do clocks simply reflect damage, mirrors to show who's the frailest of them all? Or do they programmatically drive aging? The answer involves vast complexity, like trying to deduce the direct causes of a 17-car pileup on a potholed road in foggy conditions. Except, instead of 17 cars, it's millions of epigenetic sites and thousands of potential genes, RNA molecules and blood proteins acting on aging and each other.

Because the various measures—epigenetics, microbes, etc.—capture distinct aging dimensions, an important goal is unifying them into one "mosaic of biological ages," as Levine called it. Gladyshev said more datasets are needed. Just yesterday, though, Zhavoronkov launched Deep Longevity's groundbreaking composite of metrics to consumers – something that was previously available only to clinicians. The iPhone app allows users to upload their own samples and tracks aging on multiple levels – epigenetic, behavioral, microbiome, and more. It even includes a deep psychological clock asking if people feel as old as they are. Perhaps Twain's adage about mind over matter is evidence-backed.

Zhavoronkov appeared youthful in our Zoom interview, but admitted self-testing shows an advanced age because "I do not sleep"; indeed, he'd scheduled me at midnight Hong Kong time. Perhaps explaining his insomnia, he fears economic collapse if age-related diseases cost the global economy over $30 trillion by 2030. Rather than seeking eternal life, researchers like Zhavoronkov aim to increase health span: fully living our final decades without excess pain and hospital bills.

It's also a lucrative sales pitch to 7.8 billion aging humans.

Get your bio age

Levine, the Yale scientist, has partnered with Elysium Health to sell Index, an epigenetic measure launched in late 2019, direct to consumers, using their saliva samples. Elysium will roll out additional measures as research progresses, starting with an assessment of how fast someone is accumulating cells that no longer divide. "The more measures to capture specific processes, the more we can actually understand what's unique for an individual," Levine said.

Another company, InsideTracker, with an advisory board headlined by Harvard's David Sinclair, eschews the quirkiness of epigenetics. Its new InnerAge 2.0 test, announced this month, analyzes 18 blood biomarkers associated with longevity.

"You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them."

Because aging isn't considered a disease, consumer aging tests don't require FDA approval, and some researchers are skeptical of their use in the near future. "I'm on the fence as to whether these things are ready to be rolled out," said Freeman, the Oklahoma researcher. "We need to do our traditional experimental study design to [be] confident they're actually useful."

Then, 50-year-olds who are biologically 45 may wait five years for their first colonoscopy, Barzilai said. Despite some forerunners, clinical applications for individuals are mostly prospective, yet I was intrigued. Could these clocks reveal if I'm following the footsteps of the super-agers? Or will I rack up the hospital bills of Zhavoronkov's nightmares?

I sent my blood for testing with InsideTracker. Fearing the worst—an InnerAge accelerated by a couple of decades—I asked thought leaders where this technology is headed.

Insurance 2030

With continued advances, by 2030 you'll learn your biological age with a glance at your wristwatch. You won't be the only monitor; your insurance company may send an alert if your age goes too high, threatening lost rewards.

If this seems implausible, consider that life insurer John Hancock already tracks a VitalityAge. With Obamacare incentivizing companies to engage policyholders in improving health, many are dangling rewards for fitness. BlueCross BlueShield covers 25 percent of InsideTracker's cost, and UnitedHealthcare offers a suite of such programs, including "missions" for policyholders to lower their Rally age. "People underestimate the amount of time they're sedentary," said Michael Bess, vice president of healthcare strategies. "So having this technology to drive positive reinforcement is just another way to encourage healthy behavior."

It's unclear if these programs will close health gaps, or simply attract customers already prioritizing fitness. And insurers could raise your premium if you don't measure up. Obamacare forbids discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, but will accelerated age qualify for this protection?

Liz McFall, a sociologist at the University of Edinburgh, thinks the answer depends on whether we view aging as controllable. "You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them," she said.

That outcome troubles Mark Rothstein, director of the Institute of Bioethics at the University of Louisville. "For those living with air pollution and unsafe water, in food deserts and where you can't safely exercise, then [insurers] take the results in terms of biological stressors, now you're adding insult to injury," he said.

Government could subsidize aging clocks and interventions for older people with fewer resources for controlling their health—and the greatest room for improving their epigenetic age. Rothstein supports that policy, but said, "I don't see it happening."

Bio age working for you

2030 again. A job posting seeks a "go-getter," so you attach a doctor's note to your resume proving you're ten years younger than your chronological age.

This prospect intrigued Cathy Ventrell-Monsees, senior advisor at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Any marker other than age is a step forward," she said. "Age simply doesn't determine any kind of cognitive or physical ability."

What if the assessment isn't voluntary? Armed with AI, future employers could surveil a candidate's biological age from their head-shot. Haut.ai is already marketing an uncannily accurate PhotoAgeClock. Its CEO, Anastasia Georgievskaya, noted this tech's promise in other contexts; it could help people literally see the connection between healthier lifestyles and looking young and attractive. "The images keep people quite engaged," she told me.

Updating laws could minimize drawbacks. Employers are already prohibited from using genetic information to discriminate (think 23andMe). The ban could be extended to epigenetics. "I would imagine biomarkers for aging go a similar path as genetic nondiscrimination," said McFall, the sociologist.

Will we use aging clocks to screen candidates for the highest office? Barzilai, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine researcher, believes Trump and Biden have similar biological ages. But one of Barzilai's factors, BMI, is warped by Trump miraculously getting taller. "Usually people get shorter with age," Barzilai said. "His weight has been increasing, but his BMI stays the same."

As for my bio age? InnerAge suggested I'm four years younger—and by boosting my iron levels, the program suggests, I could be younger still.

We need standards for these tests, and customers must understand their shortcomings. With such transparency, though, the benefits could be compelling. In March, Theresa Brown, a 44-year-old from Kansas, learned her InnerAge was 57.2. She followed InsideTracker's recommendations, including regular intermittent fasting. Retested five months later, her age had dropped to 34.1. "It's not that I guaranteed another 10 or 20 years to my life. It's that it encourages me. Whether I really am or not, I just feel younger. I'll take that."

Which leads back to Zhavoronkov's psychological clock. Perhaps lowering our InnerAges can be the self-fulfilling prophesy that helps Theresa and me age like the super-athletes who thrive longer than expected. McFall noted the power of simple, sufficiently credible goals for encouraging better health. Think 10,000 steps per day, she said.

Want to be 34 again? Just do it.

Yet, many people's budgets just don't allow gym memberships, nutritious groceries, or futuristic aging clocks. Bill Gates cautioned we overestimate progress in the next two years, while underestimating the next ten. Policies should ensure that age testing and interventions are distributed fairly.

"Within the next 5 to 10 years," said Gladyshev, "there will be drugs and lifestyle changes which could actually increase lifespan or healthspan for the entire population."

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business