The Skinny on Fat and Covid-19

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

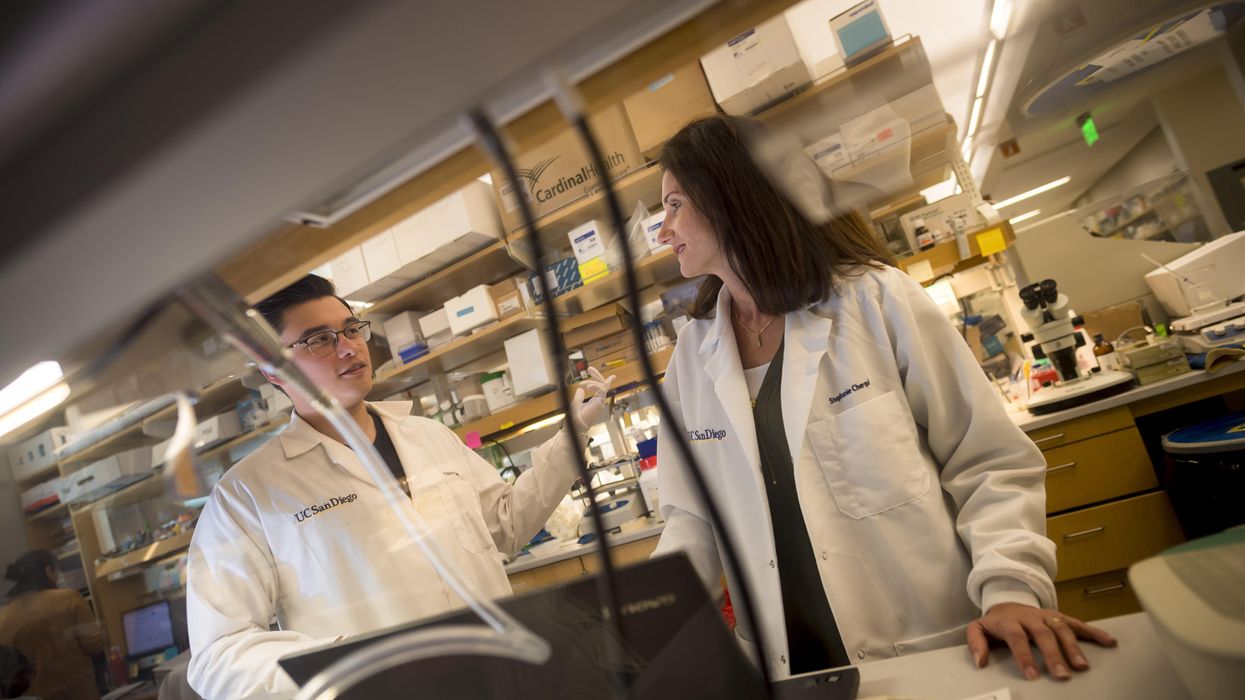

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.

New gene therapy helps patients with rare disease. One mother wouldn't have it any other way.

A biotech in Cambridge, Mass., is targeting a rare disease called cystinosis with gene therapy. It's been effective for five patients in a clinical trial that's still underway.

Three years ago, Jordan Janz of Consort, Alberta, knew his gene therapy treatment for cystinosis was working when his hair started to darken. Pigmentation or melanin production is just one part of the body damaged by cystinosis.

“When you have cystinosis, you’re either a redhead or a blonde, and you are very pale,” attests Janz, 23, who was diagnosed with the disease just eight months after he was born. “After I got my new stem cells, my hair came back dark, dirty blonde, then it lightened a little bit, but before it was white blonde, almost bleach blonde.”

According to Cystinosis United, about 500 to 600 people have the rare genetic disease in the U.S.; an estimated 20 new cases are diagnosed each year.

Located in Cambridge, Mass., AVROBIO is a gene therapy company that targets cystinosis and other lysosomal storage disorders, in which toxic materials build up in the cells. Janz is one of five patients in AVROBIO’s ongoing Phase 1/2 clinical trial of a gene therapy for cystinosis called AVR-RD-04.

Recently, AVROBIO compiled positive clinical data from this first and only gene therapy trial for the disease. The data show the potential of the therapy to genetically modify the patients’ own hematopoietic stem cells—a certain type of cell that’s capable of developing into all different types of blood cells—to express the functional protein they are deficient in. It stabilizes or reduces the impact of cystinosis on multiple tissues with a single dose.

Medical researchers have found that more than 80 different mutations to a gene called CTNS are responsible for causing cystinosis. The most common mutation results in a deficiency of the protein cystinosin. That protein functions as a transporter that regulates a lot metabolic processes in the cells.

“One of the first things we see in patients clinically is an accumulation of a particular amino acid called cystine, which grows toxic cystine crystals in the cells that cause serious complications,” explains Essra Rihda, chief medical officer for AVROBIO. “That happens in the cells across the tissues and organs of the body, so the disease affects many parts of the body.”

Jordan Janz, 23, meets Stephanie Cherqui, the principal investigator of his gene therapy trial, before the trial started in 2019.

Jordan Janz

According to Rihda, although cystinosis can occur in kids and adults, the most severe form of the disease affects infants and makes up about 95 percent of overall cases. Children typically appear healthy at birth, but around six to 18 months, they start to present for medical attention with failure to thrive.

Additionally, infants with cystinosis often urinate frequently, a sign of polyuria, and they are thirsty all the time, since the disease usually starts in the kidneys. Many develop chronic kidney disease that ultimately progresses to the point where the kidney no longer supports the body’s needs. At that stage, dialysis is required and then a transplant. From there the disease spreads to many other organs, including the eyes, muscles, heart, nervous system, etc.

“The gene for cystinosis is expressed in every single tissue we have, and the accumulation of this toxic buildup alters all of the organs of the patient, so little by little all of the organs start to fail,” says Stephanie Cherqui, principal investigator of Cherqui Lab, which is part of UC San Diego’s Department of Pediatrics.

Since the 1950s, a drug called cysteamine showed some therapeutic effect on cystinosis. It was approved by the FDA in 1994 to prevent damage that may be caused by the buildup of cystine crystals in organs. Prior to FDA approval, Cherqui says, children were dying of the disease before they were ten-years-old or after a kidney transplant. By taking oral cysteamine, they can live from 20 to 50 years longer. But it’s a challenging drug because it has to be taken every 6 or 12 hours, and there are serious gastric side effects such as nausea and diarrhea.

“With all of the complications they develop, the typical patient takes 40 to 60 pills a day around the clock,” Cherqui says. “They literally have a suitcase of medications they have to carry everywhere, and all of those medications don’t stop the progression of the disease, and they still die from it.”

Cherqui has been a proponent of gene therapy to treat children’s disorders since studying cystinosis while earning her doctorate in 2002. Today, her lab focuses on developing stem cell and gene therapy strategies for degenerative, hereditary disorders such as cystinosis that affect multiple systems of the body. “Because cystinosis expresses in every tissue in the body, I decided to use the blood-forming stem cells that we have in our bone marrow,” she explains. “These cells can migrate to anywhere in the body where the person has an injury from the disease.”

AVROBIO’s hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy approach collects stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow. They then genetically modify the stem cells to give the patient a copy of the healthy CTNS gene, which the person either doesn’t have or it’s defective.

The patient first undergoes apheresis, a medical procedure in which their blood is passed through an apparatus that separates out the diseased stem cells, and a process called conditioning is used to help eliminate the damaged cells so they can be replaced by the infusion of the patient’s genetically modified stem cells. Once they become engrafted into the patient’s bone marrow, they reproduce into a lot of daughter cells, and all of those daughter cells contain the CTNS gene. Those cells are able to express the healthy, functional, active protein throughout the body to correct the metabolic problem caused by cystinosis.

“What we’re seeing in the adult patients who have been dosed to date is the consistent and sustained engraftment of our genetically modified cells, 17 to 27 months post-gene therapy, so that’s very encouraging and positive,” says Rihda, the chief medical officer at AVROBIO.

When Janz was 11-years-old, his mother got him enrolled in the trial of a new form of cysteamine that would only need to be taken every 12 hours instead of every six. Two years later, she made sure he was the first person on the list for Cherqui’s current stem cell gene therapy trial.

AVROBIO researchers have also confirmed stabilization or improvement in motor coordination and visual perception in the trial participants, suggesting a potential impact on the neuropathology of the disease. Data from five dosed patients show strong safety and tolerability as well as reduced accumulation of cystine crystals in cells across multiple tissues in the first three patients. None of the five patients need to take oral cysteamine.

Janz’s mother, Barb Kulyk, whom he credits with always making him take his medications and keeping him hydrated, had been following Cherqui’s research since his early childhood. When Janz was 11-years-old, she got him enrolled in the trial of a new form of cysteamine that would only need to be taken every 12 hours instead of every six. When he was 17, the FDA approved that drug. Two years later, his mother made sure he was the first person on the list for Cherqui’s current stem cell gene therapy trial. He received his new stem cells on October 7th, 2019, went home in January 2020, and returned to working full time in February.

Jordan Janz, pictured here with his girlfriend, has a new lease on life, plus a new hair color.

Jordan Janz

He notes that his energy level is significantly better, and his mother has noticed much improvement in him and his daily functioning: He rarely vomits or gets nauseous in the morning, and he has more color in his face as well as his hair. Although he could finish his participation at any time, he recently decided to continue in the clinical trial.

Before the trial, Janz was taking 56 pills daily. He is completely off all of those medications and only takes pills to keep his kidneys working. Because of the damage caused by cystinosis over the course of his life, he’s down to about 20 percent kidney function and will eventually need a transplant.

“Some day, though, thanks to Dr. Cherqui’s team and AVROBIO’s work, when I get a new kidney, cystinosis won’t destroy it,” he concludes.

New study: Hotter nights, climate change, cause sleep loss with some affected more than others

According to a new study, sleep is impaired with temperatures over 50 degrees, and temps higher than 77 degrees reduce the chances of getting seven hours.

Data from the National Sleep Foundation finds that the optimal bedroom temperature for sleep is around 65 degrees Fahrenheit. But we may be getting fewer hours of "good sleepin’ weather" as the climate warms, according to a recent paper from researchers at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Published in One Earth, the study finds that heat related to climate change could provide a “pathway” to sleep deprivation. The authors say the effect is “substantially larger” for those in lower-income countries. Hours of sleep decline when nighttime temperature exceeds 50 degrees, and temps higher than 77 reduce the chances of sleeping for seven hours by 3.5 percent. Even small losses associated with rising temperatures contribute significantly to people not getting enough sleep.

We’re affected by high temperatures at night because body temperature becomes more sensitive to the environment when slumbering. “Mechanisms that control for thermal regulation become more disordered during sleep,” explains Clete Kushida, a neurologist, professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and sleep medicine clinician.

The study finds that women and older adults are especially vulnerable. Worldwide, the elderly lost over twice as much sleep per degree of warming compared to younger people. This phenomenon was apparent between the ages of 60 and 70, and it increased beyond age 70. “The mechanism for balancing temperatures appears to be more affected with age,” Kushida adds.

Others disproportionately affected include those who live in regions with more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which accelerate climate change, and people in hotter locales will lose more sleep per degree of warming, according to the study, with suboptimal temperatures potentially eroding 50 to 58 hours of sleep per person per year. One might think that those in warmer countries can adapt to the heat, but the researchers found no evidence for such adjustments. “We actually found those living in the warmest climate regions were impacted over twice as much as those in the coldest climate regions,” says the study's lead author, Kelton Minor, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Copenhagen’s Center for Social Data Science.

Short sleep can reduce cognitive performance and productivity, increase absenteeism from work or school, and lead to a host of other physical and psychosocial problems. These issues include a compromised immune system, hypertension, depression, anger and suicide, say the study’s authors. According to a fact sheet by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a third of U.S. adults already report sleeping fewer hours than the recommended amount, even though sufficient sleep “is not a luxury—it is something people need for good health.”

Equitable policy and planning are needed to ensure equal access to cooling technologies in a warming world.

Beyond global health, a sleep-deprived world will impact the economy as the climate warms. “Less productivity at work, associated with sleep loss or deprivation, would result in more sick days on a global scale, not just in individual countries,” Kushida says.

Unlike previous research that measured sleep patterns with self-reported surveys and controlled lab experiments, the study in One Earth offers a global analysis that relies on sleep-tracking wristbands that link more than seven million sleep records of 47,628 adults across 68 countries to local and daily meteorological data, offering new insight into the environmental impact on human sleep. Controlling for individual, seasonal and time-varying confounds, researchers found the main way that higher temperatures shorten slumber is by delaying sleep onset.

Heat effects on sleep were seen in industrialized countries including those with access to air conditioning, notes the study. Air conditioning may buffer high indoor temperatures, but they also increase GHG emissions and ambient heat displacement, thereby exacerbating the unequal burdens of global and local warming. Continued urbanization is expected to contribute to these problems.

Previous sleep studies have found an inverse U-shaped response to temperature in highly controlled settings, with subjects sleeping worse when room temperatures were either too cold or too warm. However, “people appear far better at adapting to colder outside temperatures than hotter conditions,” says Minor.

Although there are ways of countering the heat effect, some populations have more access to them. “Air conditioning can help with the effect of higher temperature, but not all individuals can afford air conditioners,” says Kushida. He points out that this could drive even greater inequity between higher- and lower-income countries.

Equitable policy and planning are needed to ensure equal access to cooling technologies in a warming world. “Clean and renewable energy systems and interventions will be needed to mitigate and adapt to ongoing climate warming,” Minor says. Future research should investigate “policy, planning and design innovation,” which could reduce the impact of sweltering temperatures on a good night’s sleep for the good of individuals, society and our planet, asserts the study.

Unabated and on its current trajectory, by 2099 suboptimal temperatures could shave 50 to 58 hours of sleep per person per year, predict the study authors. “Down the road, as technology develops, there might be ways of enabling people to adapt on a large scale to these higher temperatures,” says Kushida. “Right now, it’s not there.”