Some companies claim remote work hurts wellbeing. Research shows the opposite.

Leaders at Google and other companies are trying to get workers to return to the office, saying remote and hybrid work disrupt work-life boundaries and well-being. These arguments conflict with research on remote work and wellness.

Many leaders at top companies are trying to get workers to return to the office. They say remote and hybrid work are bad for their employees’ mental well-being and lead to a sense of social isolation, meaninglessness, and lack of work-life boundaries, so we should just all go back to office-centric work.

One example is Google, where the company’s leadership is defending its requirement of mostly in-office work for all staff as necessary to protect social capital, meaning people’s connections to and trust in one another. That’s despite a survey of over 1,000 Google employees showing that two-thirds feel unhappy about being forced to work in the office three days per week. In internal meetings and public letters, many have threatened to leave, and some are already quitting to go to other companies with more flexible options.

Last month, GM rolled out a policy similar to Google’s, but had to backtrack because of intense employee opposition. The same is happening in some places outside of the U.S. For instance, three-fifths of all Chinese employers are refusing to offer permanent remote work options, according to a survey this year from The Paper.

For their claims that remote work hurts well-being, some of these office-centric traditionalists cite a number of prominent articles. For example, Arthur Brooks claimed in an essay that “aggravation from commuting is no match for the misery of loneliness, which can lead to depression, substance abuse, sedentary behavior, and relationship damage, among other ills.” An article in Forbes reported that over two-thirds of employees who work from home at least part of the time had trouble getting away from work at the end of the day. And Fast Company has a piece about how remote work can “exacerbate existing mental health issues” like depression and anxiety.

For his part, author Malcolm Gladwell has also championed a swift return to the office, saying there is a “core psychological truth, which is we want you to have a feeling of belonging and to feel necessary…I know it’s a hassle to come into the office, but if you’re just sitting in your pajamas in your bedroom, is that the work life you want to live?”

These arguments may sound logical to some, but they fly in the face of research and my own experience as a behavioral scientist and as a consultant to Fortune 500 companies. In these roles, I have seen the pitfalls of in-person work, which can be just as problematic, if not more so. Remote work is not without its own challenges, but I have helped 21 companies implement a series of simple steps to address them.

Research finds that remote work is actually better for you

The trouble with the articles described above - and claims by traditionalist business leaders and gurus - stems from a sneaky misdirection. They decry the negative impact of remote and hybrid work for wellbeing. Yet they gloss over the damage to wellbeing caused by the alternative, namely office-centric work.

It’s like comparing remote and hybrid work to a state of leisure. Sure, people would feel less isolated if they could hang out and have a beer with their friends instead of working. They could take care of their existing mental health issues if they could visit a therapist. But that’s not in the cards. What’s in the cards is office-centric work. That means the frustration of a long commute to the office, sitting at your desk in an often-uncomfortable and oppressive open office for at least 8 hours, having a sad desk lunch and unhealthy snacks, sometimes at an insanely expensive cost and, for making it through this series of insults, you’re rewarded with more frustration while commuting back home.

In a 2022 survey, the vast majority of respondents felt that working remotely improved their work-life balance. Much of that improvement stemmed from saving time due to not needing to commute and having a more flexible schedule.

So what happens when we compare apples to apples? That’s when we need to hear from the horse’s mouth: namely, surveys of employees themselves, who experienced both in-office work before the pandemic, and hybrid and remote work after COVID struck.

Consider a 2022 survey by Cisco of 28,000 full-time employees around the globe. Nearly 80 percent of respondents say that remote and hybrid work improved their overall well-being: that applies to 83 percent of Millennials, 82 percent of Gen Z, 76 percent of Gen Z, and 66 percent of Baby Boomers. The vast majority of respondents felt that working remotely improved their work-life balance.

Much of that improvement stemmed from saving time due to not needing to commute and having a more flexible schedule: 90 percent saved 4 to 8 hours or more per week. What did they do with that extra time? The top choice for almost half was spending more time with family, friends and pets, which certainly helped address the problem of isolation from the workplace. Indeed, three-quarters of them report that working from home improved their family relationships, and 51 percent strengthened their friendships. Twenty percent used the freed up hours for self-care.

Of the small number who report their work-life balance has not improved or even worsened, the number one reason is the difficulty of disconnecting from work, but 82 percent report that working from anywhere has made them happier. Over half say that remote work decreased their stress levels.

Other surveys back up Cisco’s findings. For example, a 2022 Future Forum survey compared knowledge workers who worked full-time in the office, in a hybrid modality, and fully remote. It found that full-time in-office workers felt the least satisfied with work-life balance, hybrid workers were in the middle, and fully remote workers felt most satisfied. The same distribution applied to questions about stress and anxiety. A mental health website called Tracking Happiness found in a 2022 survey of over 12,000 workers that fully remote employees report a happiness level about 20 percent greater than office-centric ones. Another survey by CNBC in June found that fully remote workers are more often very satisfied with their jobs than workers who are fully in-person.

Academic peer-reviewed research provides further support. Consider a 2022 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health of bank workers who worked on the same tasks of advising customers either remotely or in-person. It found that fully remote workers experienced higher meaningfulness, self-actualization, happiness, and commitment than in-person workers. Another study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, reported that hybrid workers, compared to office-centric ones, experienced higher satisfaction with work and had 35 percent more job retention.

What about the supposed burnout crisis associated with remote work? Indeed, burnout is a concern. A survey by Deloitte finds that 77 percent of workers experienced burnout at their current job. Gallup came up with a slightly lower number of 67 percent in its survey. But guess what? Both of those surveys are from 2018, long before the era of widespread remote work.

By contrast, in a Gallup survey in late 2021, 58 percent of respondents reported less burnout. An April 2021 McKinsey survey found burnout in 54 percent of Americans and 49 percent globally. A September 2021 survey by The Hartford reported 61 percent burnout. Arguably, the increase in full or part-time remote opportunities during the pandemic helped to address feelings of burnout, rather than increasing them. Indeed, that finding aligns with the earlier surveys and peer-reviewed research suggesting remote and hybrid work improves wellbeing.

Remote work isn’t perfect – here’s how to fix its shortcomings

Still, burnout is a real problem for hybrid and remote workers, as it is for in-office workers. Employers need to offer mental health benefits with online options to help employees address these challenges, regardless of where they’re working.

Moreover, while they’re better overall for wellbeing, remote and hybrid work arrangements do have specific disadvantages around work-life separation. To address work-life issues, I advise my clients who I helped make the transition to hybrid and remote work to establish norms and policies that focus on clear expectations and setting boundaries.

For working at home and collaborating with others, there’s sometimes an unhealthy expectation that once you start your workday in your home office chair, and that you’ll work continuously while sitting there.

Some people expect their Slack or Microsoft Teams messages to be answered within an hour, while others check Slack once a day. Some believe email requires a response within three hours, and others feel three days is fine. As a result of such uncertainty and lack of clarity about what’s appropriate, too many people feel uncomfortable disconnecting and not replying to messages or doing work tasks after hours. That might stem from a fear of not meeting their boss’s expectations or not wanting to let their colleagues down.

To solve this problem, companies need to establish and incentivize clear expectations and boundaries. They should develop policies and norms around response times for different channels of communication. They also need to clarify work-life boundaries – for example, the frequency and types of unusual circumstances that will require employees to work outside of regular hours.

Moreover, for working at home and collaborating with others, there’s sometimes an unhealthy expectation that once you start your workday in your home office chair, and that you’ll work continuously while sitting there (except for your lunch break). That’s not how things work in the office, which has physical and mental breaks built in throughout the day. You took 5-10 minutes to walk from one meeting to another, or you went to get your copies from the printer and chatted with a coworker on the way.

Those and similar physical and mental breaks, research shows, decrease burnout, improve productivity, and reduce mistakes. That’s why companies should strongly encourage employees to take at least a 10-minute break every hour during remote work. At least half of those breaks should involve physical activity, such as stretching or walking around, to counteract the dangerous effects of prolonged sitting. Other breaks should be restorative mental activities, such as meditation, brief naps, walking outdoors, or whatever else feels restorative to you.

To facilitate such breaks, my client organizations such as the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute shortened hour-long meetings to 50 minutes and half-hour meetings to 25 minutes, to give everyone – both in-person and remote workers – a mental and physical break and transition time.

Very few people will be reluctant to have shorter meetings. After that works out, move to other aspects of setting boundaries and expectations. Doing so will require helping team members get on the same page and reduce conflicts and tensions. By setting clear expectations, you’ll address the biggest challenge for wellbeing for remote and hybrid work: establishing clear work-life boundaries.

Podcast: The Friday Five Weekly Roundup in Health Research

In this week's Friday Five, a new face mask can detect Covid and send an alert to your phone. Plus, promising research for a breakthrough drug to treat schizophrenia, an AI tool that can create new proteins, progress on a longevity drug - and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- A new mask can detect Covid and send an alert to your phone

- More promising research for a breakthrough drug to treat schizophrenia

- AI tool can create new proteins

- Connections between an unhealthy gut and breast cancer

- Progress on the longevity drug, rapamycin

And an honorable mention this week: Certain exercises may benefit some types of memory more than others

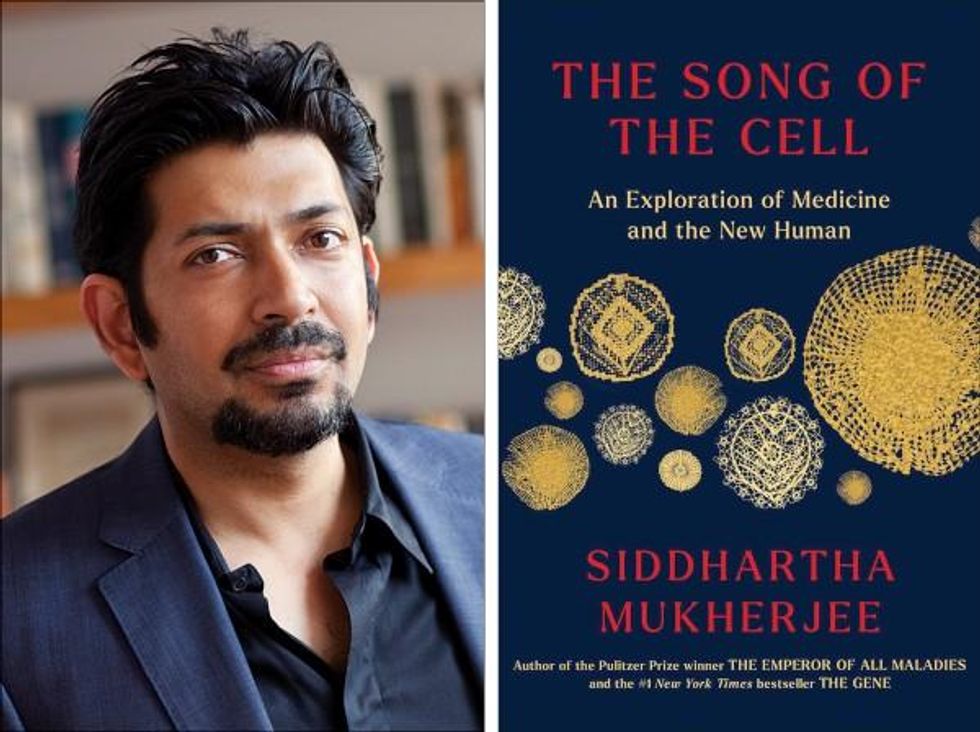

Life is Emerging: Review of Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Song of the Cell

A new book by Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee will be released from Simon & Schuster on October 25, 2022.

The DNA double helix is often the image spiraling at the center of 21st century advances in biomedicine and the growing bioeconomy. And yet, DNA is molecularly inert. DNA, the code for genes, is not alive and is not strictly necessary for life. Ought life be at the center of our communication of living systems? Is not the Cell a superior symbol of life and our manipulation of living systems?

A code for life isn’t a code without the life that instantiates it. A code for life must be translated. The cell is the basic unit of that translation. The cell is the minimal viable package of life as we know it. Therefore, cell biology is at the center of biomedicine’s greatest transformations, suggests Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee in his latest book, The Song of the Cell: The Exploration of Medicine and the New Human.

The Song of the Cell begins with the discovery of cells and of germ theory, featuring characters such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, who brought the cell “into intimate contact with pathology and medicine.” This intercourse would transform biomedicine, leading to the insight that we can treat disease by thinking at the cellular level. The slightest rearrangement of sick cells might be the path toward alleviating suffering for the organism: eroding the cell walls of a bacterium while sparing our human cells; inventing a medium that coaxes sperm and egg to dance into cellular union for in vitro fertilization (IVF); designing molecular missiles that home to the receptors decorating the exterior of cancer cells; teaching adult skin cells to remember their embryonic state for regenerative medicines.

Mukherjee uses the bulk of the book to elucidate key cell types in the human body, along with their “connective relationships” that enable key organs and organ systems to function. This includes the immune system, the heart, the brain, and so on. Mukherjee’s distinctive style features compelling anecdotes and human stories that animate the scientific (and unscientific) processes that have led to our current state of understanding. In his chapter on neurons and the brain, for example, he integrates Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s meticulous black ink sketches of neurons into Mukherjee’s own personal encounter with clinical depression. In one lucid section, he interviews Dr. Helen Mayberg, a pioneering neurologist who takes seriously the descriptive power of her patients’ metaphors, as they suffer from “caves,” “holes,” “voids,” and “force fields” that render their lives gray. Dr. Mayberg aims to stimulate patients’ neuronal cells in a manner that brings back the color.

Beyond exposing the insight and inventiveness that has arisen out of cell-based thinking, it seems that Mukherjee’s bigger project is an epistemological one. The early chapters of The Song of the Cell continually hint at the potential for redefining the basic unit of biology as the cell rather than the gene. The choice to center biomedicine around cells is, above all, a conspicuous choice not to center it around genes (the subject of Mukherjee’s previous book, The Gene), because genes dominate popular science communication.

This choice of cells over genes is most welcome. Cells are alive. Genes are not. Letters—such as the As, Cs, Gs, and Ts that represent the nucleotides of DNA, which make up our genes—must be synthesized into a word or poem or song that offers a glimpse into deeper truths. A key idea embedded in this thinking is that of emergence. Whether in ancient myth or modern art, creation tends to be an emergent process, not a linearly coded script. The cell is our current best guess for the basic unit of life’s emergence, turning a finite set of chemical building blocks—nucleic acids, proteins, sugars, fats—into a replicative, evolving system for fighting stasis and entropy. The cell’s song is one for our times, for it is the song of biology’s emergence out of chemistry and physics, into the “frenetically active process” of homeostasis.

Re-centering our view of biology has practical consequences, too, for how we think about diagnosing and treating disease, and for inventing new medicines. Centering cells presents a challenge: which type of cell to place at the center? Rather than default to the apparent simplicity of DNA as a symbol because it represents the one master code for life, the tension in defining the diversity of cells—a mapping process still far from complete in cutting-edge biology laboratories—can help to create a more thoughtful library of cellular metaphors to shape both the practice and communication of biology.

Further, effective problem solving is often about operating at the right level, or the right scale. The cell feels like appropriate level at which to interrogate many of the diseases that ail us, because the senses that guide our own perceptions of sickness and health—the smoldering pain of inflammation, the tunnel vision of a migraine, the dizziness of a fluttering heart—are emergent.

This, unfortunately, is sort of where Mukherjee leaves the reader, under-exploring the consequences of a biology of emergence. Many practical and profound questions have to do with the ways that each scale of life feeds back on the others. In a tome on Cells and “the future human” I wished that Mukherjee had created more space for seeking the ways that cells will shape and be shaped by the future, of humanity and otherwise.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts.

For example, when discussing the regenerative power of pluripotent stem cells, Mukherjee raises the philosophical thought experiment of the Delphic boat, also known as the Ship of Theseus. The boat is made of many pieces of wood, each of which is replaced for repairs over the years, with the boat’s structure unchanged. Eventually none of the boat’s original wood remains: Is it the same boat?

Mukherjee raises the Delphic boat in one paragraph at the end of the chapter on stem cells, as a metaphor related to the possibility of stem cell-enabled regeneration in perpetuity. He does not follow any of the threads of potential answers. Given the current state of cellular engineering, about which Mukherjee is a world expert from his work as a physician-scientist, this book could have used an entire section dedicated to probing this question and, importantly, the ways this thought experiment falls apart.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts. Wholeness at any one of these scales of life—organelle, cell, organ, body, ecosystem—is what is at stake if we allow biological reductionism to assume away the relation between those scales.

In other words, Mukherjee succeeds in providing a masterful and compelling narrative of the lives of many of the cells that emerge to enliven us. Like his previous books, it is a worthwhile read for anyone curious about the role of cells in disease and in health. And yet, he fails to offer the broader context of The Song of the Cell.

As leading agronomist and essayist Wes Jackson has written, “The sequence of amino acids that is at home in the human cell, when produced inside the bacterial cell, does not fold quite right. Something about the E. coli internal environment affects the tertiary structure of the protein and makes it inactive. The whole in this case, the E. coli cell, affects the part—the newly made protein. Where is the priority of part now?” [1]

Beyond the ways that different kingdoms of life translate the same genetic code, the practical situation for humanity today relates to the ways that the different disciplines of modern life use values and culture to influence our genes, cells, bodies, and environment. It may be that humans will soon become a bit like the Delphic boat, infused with the buzz of fresh cells to repopulate different niches within our bodies, for healthier, longer lives. But in biology, as in writing, a mixed metaphor can cause something of a cacophony. For we are not boats with parts to be replaced piecemeal. And nor are whales, nor alpine forests, nor topsoil. Life isn’t a sum of parts, and neither is a song that rings true.

[1] Wes Jackson, "Visions and Assumptions," in Nature as Measure (p. 52-53).