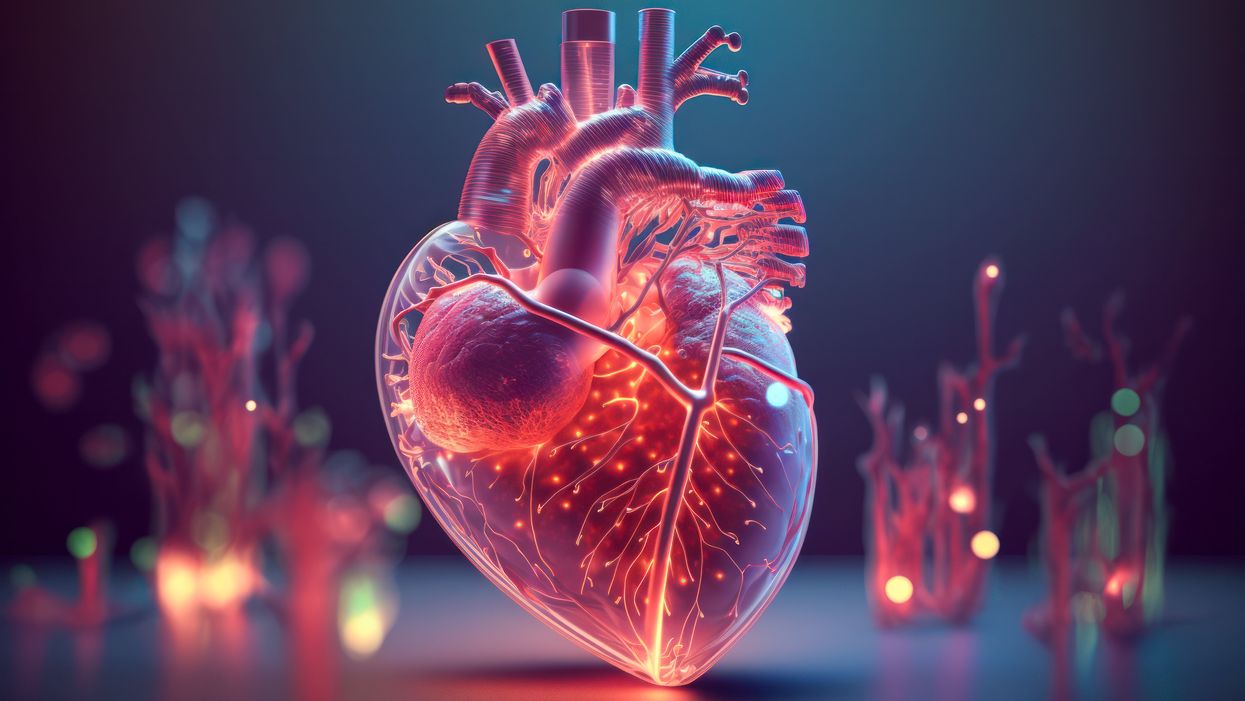

Scientists make progress with growing organs for transplants

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have laid the foundations for growing synthetic embryos that could develop a beating heart, gut and brain.

Story by Big Think

For over a century, scientists have dreamed of growing human organs sans humans. This technology could put an end to the scarcity of organs for transplants. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The capability to grow fully functional organs would revolutionize research. For example, scientists could observe mysterious biological processes, such as how human cells and organs develop a disease and respond (or fail to respond) to medication without involving human subjects.

Recently, a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge has laid the foundations not just for growing functional organs but functional synthetic embryos capable of developing a beating heart, gut, and brain. Their report was published in Nature.

The organoid revolution

In 1981, scientists discovered how to keep stem cells alive. This was a significant breakthrough, as stem cells have notoriously rigorous demands. Nevertheless, stem cells remained a relatively niche research area, mainly because scientists didn’t know how to convince the cells to turn into other cells.

Then, in 1987, scientists embedded isolated stem cells in a gelatinous protein mixture called Matrigel, which simulated the three-dimensional environment of animal tissue. The cells thrived, but they also did something remarkable: they created breast tissue capable of producing milk proteins. This was the first organoid — a clump of cells that behave and function like a real organ. The organoid revolution had begun, and it all started with a boob in Jello.

For the next 20 years, it was rare to find a scientist who identified as an “organoid researcher,” but there were many “stem cell researchers” who wanted to figure out how to turn stem cells into other cells. Eventually, they discovered the signals (called growth factors) that stem cells require to differentiate into other types of cells.

For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells.

By the end of the 2000s, researchers began combining stem cells, Matrigel, and the newly characterized growth factors to create dozens of organoids, from liver organoids capable of producing the bile salts necessary for digesting fat to brain organoids with components that resemble eyes, the spinal cord, and arguably, the beginnings of sentience.

Synthetic embryos

Organoids possess an intrinsic flaw: they are organ-like. They share some characteristics with real organs, making them powerful tools for research. However, no one has found a way to create an organoid with all the characteristics and functions of a real organ. But Magdalena Żernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist, might have set the foundation for that discovery.

Żernicka-Goetz hypothesized that organoids fail to develop into fully functional organs because organs develop as a collective. Organoid research often uses embryonic stem cells, which are the cells from which the developing organism is created. However, there are two other types of stem cells in an early embryo: stem cells that become the placenta and those that become the yolk sac (where the embryo grows and gets its nutrients in early development). For a human embryo (and its organs) to develop successfully, there needs to be a “dialogue” between these three types of stem cells. In other words, Żernicka-Goetz suspected the best way to grow a functional organoid was to produce a synthetic embryoid.

As described in the aforementioned Nature paper, Żernicka-Goetz and her team mimicked the embryonic environment by mixing these three types of stem cells from mice. Amazingly, the stem cells self-organized into structures and progressed through the successive developmental stages until they had beating hearts and the foundations of the brain.

“Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart [and] all the components that go on to make up the body,” said Żernicka-Goetz. “It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years and major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it.”

If the methods developed by Żernicka-Goetz’s team are successful with human stem cells, scientists someday could use them to guide the development of synthetic organs for patients awaiting transplants. It also opens the door to studying how embryos develop during pregnancy.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.