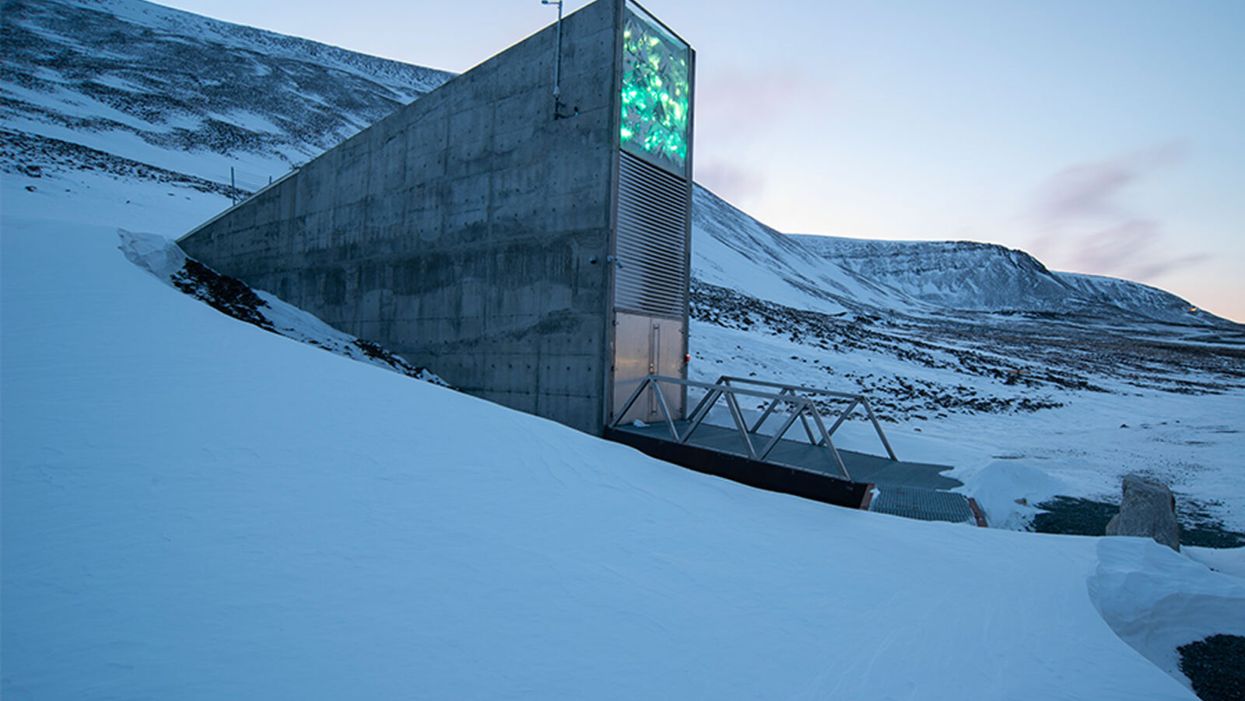

Over 1 Million Seeds Are Buried Near the North Pole to Back Up the World’s Crops

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault preserves more than one million of the world's seeds deep inside Platäfjellet Mountain.

The impressive structure protrudes from the side of a snowy mountain on the Svalbard Archipelago, a cluster of islands about halfway between Norway and the North Pole.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost. We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

Art installations on the building's rooftop and front façade glimmer like diamonds in the polar night, but it is what lies buried deep inside the frozen rock, 475 feet from the building's entrance, that is most precious. Here, in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, are backup copies of more than a million of the world's agricultural seeds.

Inside the vault, seed boxes from many gene banks and many countries. "The seeds don't know national boundaries," says Kent Nnadozie, the UN's Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

(Photo credit: Svalbard Global Seed Vault/Riccardo Gangale)

The Svalbard vault -- which has been called the Doomsday Vault, or a Noah's Ark for seeds -- preserves the genetic materials of more than 6000 crop species and their wild relatives, including many of the varieties within those species. Svalbard's collection represents all the traits that will enable the plants that feed the world to adapt – with the help of farmers and plant breeders – to rapidly changing climactic conditions, including rising temperatures, more intense drought, and increasing soil salinity. "We save these seeds because we want to ensure food security for future generations," says Grethe Helene Evjen, Senior Advisor at the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food .

A recent study in the journal Nature predicted that global warming could cause catastrophic losses of biodiversity in regions across the globe throughout this century. Yet global warming also threatens the permafrost that surrounds the seed vault, the very thing that was once considered a failsafe means of keeping these seeds frozen and safeguarding the diversity of our crops. In fact, record temperatures in Svalbard a few years ago – and a significant breach of water into the access tunnel to the vault -- prompted the Norwegian government to invest $20 million euros on improvements at the facility to further secure the genetic resources locked inside. The hope: that technology can work in concert with nature's freezer to keep the world's seeds viable.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost," says Hege Njaa Aschim, a spokesperson for Statsbygg, the government agency that recently completed the upgrades at the seed vault. "We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

The Apex of the Global Conservation System

More than 1700 genebanks around the globe preserve the diverse seed varieties from their regions. They range from small community seed banks in developing countries, where small farmers save and trade their seeds with growers in nearby villages, to specialized university collections, to national and international genetic resource repositories. But many of these facilities are vulnerable to war, natural disasters, or even lack of funding.

"If anything should happen to the resources in a regular genebank, Svalbard is the backup – it's essentially the apex of the global conservation system," says Kent Nnadozie, Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture at the United Nations, who likens the Global Vault to the Central Reserve Bank. "You have regular banks that do active trading, but the Central Bank is the final reserve where the banks store their gold deposits."

Similarly, farmers deposit their seeds in regional genebanks, and also look to these banks for new varieties to help their crops adapt to, say, increasing temperatures, or resist intrusive pests. Regional banks, in turn, store duplicates from their collections at Svalbard. These seeds remain the sovereign property of the country or institution depositing them; only they can "make a withdrawal."

The Global Vault has already proven invaluable: The International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), formerly located outside of Aleppo, Syria, held more than 140,000 seed samples, including plants that were extinct in their natural habitats, before the Syrian Crisis in 2012. Fortunately, they had managed to back up most of their seed samples at Svalbard before they were forced to relocate to Lebanon and Morocco. In 2017, ICARDA became the first – and only – organization to withdraw their stored seeds. They have now regenerated almost all of the samples at their new locations and recently redeposited new seeds for safekeeping at Svalbard.

Rapid Global Warming Threatens Permafrost

The Global Vault, a joint venture between the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) that started operating in 2008, was sited in Svalbard in part because of its remote yet accessible location: Svalbard is the northernmost inhabited spot on Earth with an airport. But experts also thought it a failsafe choice for long-term seed storage because its permafrost would offer natural freezing – even if cooling systems were to fail. No one imagined that the permafrost could fail.

"We've had record temperatures in the region recently, and there are a lot of signs that global warming is happening faster at the extreme latitudes," says Geoff Hawtin, a world-renowned authority in plant conservation, who is the founding director of -- and now advisor to -- the Crop Trust. "Svalbard is still arguably one of the safest places for the seeds from a temperature point of view, but it's actually not going to be as cold as we thought 20 years ago."

A recent report by the Norwegian Centre for Climate Services predicted that Svalbard could become 50 degrees Fahrenheit warmer by the year 2100. And data from the Norwegian government's environmental monitoring system in Svalbard shows that the permafrost is already thawing: The "active layer," that is, the layer of surface soil that seasonally thaws, has become 25-30 cm thicker since 1998.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization.

Though the permafrost surrounding the seed vault chambers, which are situated well below the active layer, is still intact, the permafrost around the access tunnel never re-established as expected after construction of the Global Vault twelve years ago. As a result, when Svalbard saw record high temperatures and unprecedented rainfall in 2016, about 164 feet of rainwater and snowmelt leaked into the tunnel, turning it into a skating rink and spurring authorities to take what they called a "better safe than sorry approach." They invested in major upgrades to the facility. "The seeds in the vault were never threatened," says Aschim, "but technology has become more important at Svalbard."

Technology Gives Nature a Boost

For now, the permafrost deep inside the mountain still keeps the temperature in the vault down to about -25°F. The cooling systems then give nature a mechanical boost to keep the seed vault chilled even further, to about -64°F, the optimal temperature for conserving seeds. In addition to upgrading to a more effective and sustainable cooling system that runs on CO2, the Norwegian government added backup generators, removed heat-generating electrical equipment from inside the facility to an outside building, installed a thick, watertight door to the vault, and replaced the corrugated steel access tunnel with a cement tunnel that uses the same waterproofing technology as the North Sea oil platforms.

To re-establish the permafrost around the tunnel, they layered cooling pipes with frozen soil around the concrete tunnel, covered the frozen soil with a cooling mat, and topped the cooling mat with the original permafrost soil. They also added drainage ditches on the mountainside to divert meltwater away from the tunnel as the climate gets warmer and wetter.

New Deposits to the Global Vault

The day before COVID-19 arrived in Norway, on February 25th, Prime Minister Erna Solberg hosted the biggest seed-depositing event in the vault's history in honor of the new and improved vault. As snow fell on Svalbard, depositors from almost every continent traveled the windy road from Longyearbyen up Platåfjellet Mountain and braved frigid -8°F weather to celebrate the massive technical upgrades to the facility – and to hand over their seeds.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization, and Israel's University of Haifa, whose deposit included multiple genotypes of wild emmer wheat, an ancient relative of the modern domesticated crop. The storage boxes carried ceremoniously over the threshold that day contained more than 65,000 new seed samples, bringing the total to more than a million, and almost filling the first of three seed chambers in the vault. (The Global Vault can store up to 4.5 million seed samples.)

"Svalbard's samples contain all the possibilities, all the options for the future of our agricultural crops – it's how crops are going to adapt," says Cary Fowler, former executive director of the Crop Trust, who was instrumental in establishing the Global Vault. "If our crops don't adapt to climate change, then neither will we." Dr. Fowler says he is confident that with the recent improvements in the vault, the seeds are going to remain viable for a very long time.

"It's sometimes tempting to get distracted by the romanticism of a seed vault inside a mountain near the North Pole – it's a little bit James Bondish," muses Dr. Fowler. "But the reality is we've essentially put an end to the extinction of more than a million samples of biodiversity forever."

In this week's Friday Five, breathing this way may cut down on anxiety, a fasting regimen that could make you sick, this type of job makes men more virile, 3D printed hearts could save your life, and the role of metformin in preventing dementia.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five, featuring interviews with Dr. David Spiegel, associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, and Dr. Filip Swirski, professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five, featuring interviews with Dr. David Spiegel, associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, and Dr. Filip Swirski, professor of medicine and cardiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

- Breathing this way cuts down on anxiety*

- Could your fasting regimen make you sick?

- This type of job makes men more virile

- 3D printed hearts could save your life

- Yet another potential benefit of metformin

* This video with Dr. Andrew Huberman of Stanford shows exactly how to do the breathing practice.

This podcast originally aired on March 3, 2023.

Breakthrough drones deliver breast milk in rural Uruguay

A drone hovers over Tacuarembó hospital in Uruguay, carrying its precious cargo: breast milk intended for children in remote parts of the country.

Until three months ago, nurse Leopoldina Castelli used to send bottles of breast milk to nourish babies in the remote areas of Tacuarembó, in northern Uruguay, by way of ambulances or military trucks. That is, if the vehicles were available and the roads were passable, which wasn’t always the case. Now, five days per week, she stands by a runway at the hospital, located in Tacuarembó’s capital, watching a drone take off and disappear from view, carrying the milk to clinics that serve the babies’ families.

The drones can fly as far as 62 miles. Long distances and rough roads are no obstacles. The babies, whose mothers struggle to produce sufficient milk and cannot afford formula, now receive ample supplies for healthy growth. “Today we provided nourishment to a significantly larger number of children, and this is something that deeply moves me,” Castelli says.

About two decades ago, the Tacuarembó hospital established its own milk bank, supported by donations from mothers across Tacuarembó. Over the years, the bank has provided milk to infants immediately after birth. It's helped drive a “significant and sustained” decrease in infant mortality, says the hospital director, Ciro Ferreira.

But these children need breast milk throughout their first six months, if not longer, to prevent malnutrition and other illnesses that are prevalent in rural Tacuarembó. Ground transport isn't quick or reliable enough to meet this goal. It can take several hours, during which the milk may spoil due to a lack of refrigeration.

The battery-powered drones have been the difference-maker. The project to develop them, financed by the UNICEF Innovation Fund, is the first of its kind in Latin America. To Castelli, it's nothing short of a revolution. Tacuarembó Hospital, along with three rural clinics in the most impoverished part of Uruguay, are its leaders.

"This marks the first occasion when the public health system has been directly impacted [by our technology]," says Sebastián Macías, the CEO and co-founder of Cielum, an engineer at the University Republic, which collaborated on the technology with a Uruguayan company called Cielum and a Swiss company, Rigitech.

The drone can achieve a top speed of up to 68 miles per hour, is capable of flying in light rain, and can withstand winds of up to 30 miles per hour at a maximum altitude of 120 meters.

"We have succeeded in embracing the mothers from rural areas who were previously slipping through the cracks of the system," says Ferreira, the hospital director. He envisions an expansion of the service so it can improve health for children in other rural areas.

Nurses load the drone for breast milk delivery.

Sebastián Macías - Cielum

The star aircraft

The drone, which costs approximately $70,000, was specifically designed for the transportation of biological materials. Constructed from carbon fiber, it's three meters wide, two meters long and weighs 42 pounds when fully loaded. Additionally, it is equipped with a ballistic parachute to ensure a safe descent in case the technology fails in midair. Furthermore, it can achieve a top speed of 68 miles per hour, fly in light rain, and withstand winds of 30 miles per hour at a height of 120 meters.

Inside, the drones feature three refrigerated compartments that maintain a stable temperature and adhere to the United Nations’ standards for transporting perishable products. These compartments accommodate four gallons or 6.5 pounds of cargo. According to Macías, that's more than sufficient to carry a week’s worth of milk for one infant on just two flights, or 3.3 pounds of blood samples collected in a rural clinic.

“From an energy perspective, it serves as an efficient mode of transportation and helps reduce the carbon emissions associated with using an ambulance,” said Macías. Plus, the ambulance can remain available in the town.

Macías, who has led software development for the drone, and three other technicians have been trained to operate it. They ensure that the drone stays on course, monitor weather conditions and implement emergency changes when needed. The software displays the in-flight positions of the drones in relation to other aircraft. All agricultural planes in the region receive notification about the drone's flight path, departure and arrival times, and current location.

The future: doubling the drone's reach

Forty-five days after its inaugural flight, the drone is now making five flights per week. It serves two routes: 34 miles to Curtina and 31 miles to Tambores. The drone reaches Curtina in 50 minutes while ambulances take double that time, partly due to the subpar road conditions. Pueblo Ansina, located 40 miles from the state capital, will soon be introduced as the third destination.

Overall, the drone’s schedule is expected to become much busier, with plans to accomplish 20 weekly flights by the end of October and over 30 in 2024. Given the drone’s speed, Macías is contemplating using it to transport cancer medications as well.

“When it comes to using drones to save lives, for us, the sky is not the limit," says Ciro Ferreira, Tacuarembó hospital director.

In future trips to clinics in San Gregorio de Polanco and Caraguatá, the drone will be pushed to the limit. At these locations, a battery change will be necessary, but it's worth it. The route will cover up to 10 rural Tacuarembó clinics plus one hospital outside Tacuarembó, in Rivera, close to the border with Brazil. Currently, because of a shortage of ambulances, the delivery of pasteurized breast milk to Rivera only occurs every 15 days.

“The expansion to Rivera will include 100,000 more inhabitants, doubling the healthcare reach,” said Ferreira, the director of the Tacuarembó Hospital. In itself, Ferreira's hospital serves the medical needs of 500,000 people as one of the largest in Uruguay's interior.

Alejandro Del Estal, an aeronautical engineer at Rigitech, traveled from Europe to Tacuarembó to oversee the construction of the vertiports – the defined areas that can support drones’ take-off and landing – and the first flights. He pointed out that once the flight network between hospitals and rural polyclinics is complete in Uruguay, it will rank among the five most extensive drone routes in the world for any activity, including healthcare and commercial uses.

Cielum is already working on the long-term sustainability of the project. The aim is to have more drones operating in other rural regions in the western and northern parts of the country. The company has received inquiries from Argentina and Colombia, but, as Macías pointed out, they are exercising caution when making commitments. Expansion will depend on the development of each country’s regulations for airspace use.

For Ferreira, the advantages in Uruguay are evident: "This approach enables us to bridge the geographical gap, enhance healthcare accessibility, and reduce the time required for diagnosing and treating rural inhabitants, all without the necessity of them traveling to the hospital,” he says. "When it comes to using drones to save lives, for us, the sky is not the limit."