The Scientist Behind the Pap Smear Saved Countless Women from Cervical Cancer

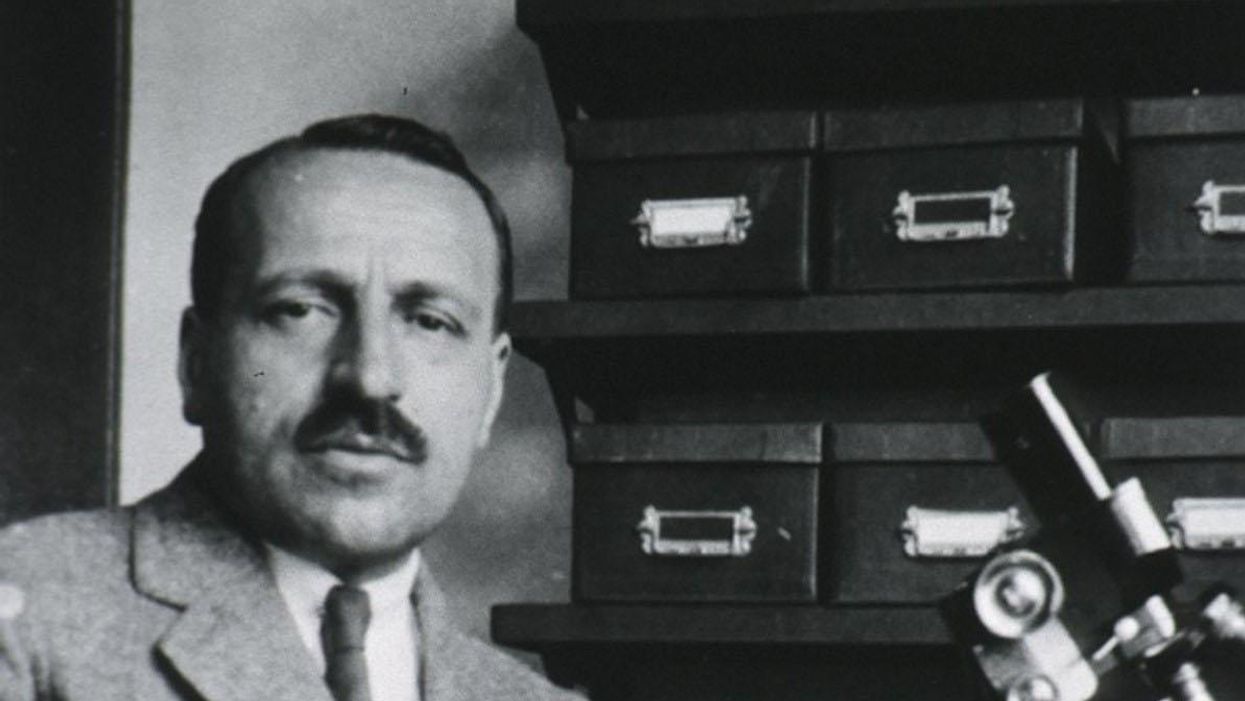

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.

Current research pipelines in biotech could take over a decade unless the heightened attention garners more resources, experts say.

Since March, 35 patients in the care of Dr. Gregory Jicha, a neurologist at the University of Kentucky, have died of Alzheimer's disease or related dementia.

Meanwhile, with 233 active clinical trials underway to find treatments, Jicha wonders why mainstream media outlets don't do more to highlight potential solutions to the physical, emotional and economic devastation of these diseases. "Unfortunately, it's not until we're right at the cusp of a major discovery that anybody pays attention to these very promising agents," he says.

Heightened awareness would bring more resources for faster progress, according to Jicha. Otherwise, he's concerned that current research pipelines will take over a decade.

In recent years, newspapers with national readerships have devoted more technology reporting to key developments in social media, artificial intelligence, wired gadgets and telecom. Less prominent has been news about biotech—innovations based on biology research—and new medicines emerging from this technology. That's the impression of Jicha as well as Craig Lipset, former head of clinical innovation at Pfizer. "Scientists and clinicians are entirely invested [in biotech], yet no one talks about their discoveries," he says.

With the popular press rightly focusing on progress with a vaccine for COVID-19 this year, notable developments in biomarkers, Alzheimer's and cancer research, gene therapies for cystic fibrosis, and therapeutics related to biological age may be going unreported. Jennifer Goldsack, Executive Director of the nonprofit Digital Medicine Society, is confused over the media's soft touch with biotech. "I'm genuinely interested in understanding what editors of technology sections think the public wants to be reading."

The Numbers on Media Coverage

A newspaper's health section is a sensible fit for biotech reporting. In 2020, these departments have concentrated largely on COVID-19—as they should—while sections on technology and science don't necessarily pick up on other biotech news. Emily Mullin, staff writer for the tech magazine OneZero, has observed a gap in newspaper coverage. "You have a lot of [niche outlets] reporting biotech on the business side for industry experts, and you have a lot of reporting heavily from the science side focused on [readers who are] scientists. But there aren't a lot of outlets doing more humanizing coverage of biotech."

Indeed, the volume of coverage by top-tier media outlets in the U.S. for non-COVID biotech has dropped 32 percent since the pandemic spiked in March, according to an analysis run for this article by Commetric, a company that looks at media reputation for clients in many sectors including biotech and artificial intelligence. Meanwhile, the volume of coverage for AI has held steady, up one percent.

Commetric's CEO, Magnus Hakansson, thinks important biotech stories were omitted from mainstream coverage even before the world fell into the grips of the virus. "Apart from COVID, it's been extremely difficult for biotech companies to push out their discoveries," he says. "People in biotech have to be quite creative when they want to communicate [progress in] different therapeutic areas, and that is a problem."

In mid-February, just before the pandemic dominated the news cycle, researchers used machine learning to find a powerful new antibiotic capable of killing strains of disease-causing bacteria that had previously resisted all known antibiotics. Science-focused outlets hailed the work as a breakthrough, but some nationally-read newspapers didn't mention it. "There is this very silent crisis around antibiotic resistance that no one is aware of," says Goldsack. "We could be 50 years away from not being able to give elective surgeries because we are at such a high risk of being unable to control infection."

Could mainstream media strike a better balance between cynicism toward biotech and hyping animal studies that probably won't ever benefit the humans reading about them?

What's to Gain from More Mainstream Biotech

A brighter public spotlight on biotech could result in greater support and faster progress with research, says Lipset. "One of the biggest delays in drug development is patient recruitment. Patients don't know about the opportunities," he said, because, "clinical research pipelines aren't talked about in the mainstream news." Only about eight percent of oncology patients participate.

The current focus on COVID-19, while warranted, could also be excluding lines of research that seem separate from the virus, but are actually relevant. In September, Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute of Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, told me about eight different observational studies finding decreased COVID-19 severity among people taking a drug called metformin, which is believed to slow down the major hallmarks of biological aging, such as inflammation. Once a vaccine is approved and distributed, biologically older people could supplement it with metformin.

"Shining the spotlight on this research now could really be critical because COVID has shown what happens in older adults and how they're more at risk," says Jenna Bartley, a researcher of aging and immunology at the University of Connecticut, but she believes mainstream media sometimes miss stories on anti-aging therapies or portray them inaccurately.

The question remains why.

The Theranos Effect and Other Image Problems

Before the pandemic, Mullin, the biotech writer at OneZero, looked into a story for her editor about a company with a new test for infectious diseases. The company said its test, based on technology for editing genes, was fast, easy to use, and could be tailored to any pathogen. Mullin told her editor the evidence for the test's validity was impressive.

He wondered if readers would agree. "This is starting to sound like Theranos," he said.

The brainchild of entrepreneur Elizabeth Holmes, Theranos was valued at $9 billion in 2014. Time Magazine named Holmes one of its most influential people, and the blood-testing company was heavily covered by the media as a game changer for health outcomes—until Holmes was exposed by the Wall Street Journal as a fraud and criminally charged.

In the OneZero article, Mullin and her editor were careful to explain the gene-editing tech was legit, explicitly distinguishing it from Theranos. "I was like, yes—but this actually works! And they can show it works."

While the Holmes scandal explains some of the mistrust, it's part of a bigger pattern. The public's hopes for biotech have been frustrated repeatedly in recent decades, fostering a media mantra of fool me twice, shame on me. A recent report by Commetric noted that after the bursting of the biotech market bubble in the early 2000s, commentators grew deeply skeptical of the field. An additional source of caution may be the number of researchers in biotech with conflicts of interest such as patents or their own startups. "It's a landmine," Mullin said. "We're conditioned to think that scientists are out for the common good, but they have their own biases."

Yet another source of uncertainty: the long regulatory road and cost for new therapies to be approved by the FDA. The process can take 15 years and over a billion dollars; the percentage of drugs actually crossing the final strand of red tape is notoriously low.

"The only time stories have reached the news is when there's a sensational headline about the cure for cancer," said Lipset, "when, in fact it's about mice, and then things drop off." Meanwhile, consumer protection hurdles for some technologies, such as computer chips, are less onerous than the FDA gauntlet for new medicines. The media may view research breakthroughs in digital tech as more impactful because they're likelier to find their way into commercially available products.

And whereas a handful of digital innovations have been democratized for widespread consumption—96 percent of Americans now own a cell phone, and 72 percent use social media—journalists at nationally-read newspapers may see biotech as less attainable for the average reader. Sure, we're all aging, but will the healthcare system grant everyone fair access to treatments for slowing the aging process? Current disparities in healthcare sow reason for doubt.

And yet. Recall Lipset's point that more press coverage would drive greater participation in clinical trials, which could accelerate them and diversify participants. Could mainstream media strike a better balance between cynicism toward biotech and hyping animal studies that probably won't ever benefit the humans reading about them?

Biotech in a Post-COVID World

Imagine it's early 2022. Hopefully, much of the population is protected from the virus through some combination of vaccines, therapeutics, and herd immunity. We're starting to bounce back from the social and economic shocks of 2020. COVID-19 headlines recede from the front pages, then disappear altogether. Gradually, certain aspects of life pick up where they left off in 2019, while a few changes forced by the pandemic prove to be more lasting, some for the better.

Among its possible legacies, the virus could usher in a new era of biotech development and press coverage, with these two trends reinforcing each other. While government has mismanaged its response to the virus, the level of innovation, collaboration and investment in pandemic-related biotech has been compared to the Manhattan Project. "There's no question that vaccine acceleration is a success story," said Kevin Schulman, a professor of medicine and economics at Stanford. "We could use this experience to build new economic models to correct market failures. It could carry over to oncology or Alzheimer's."

As Winston Churchill said, never let a good crisis go to waste.

Lipset thinks the virus has primed us to pay attention, bringing biotech into the public's consciousness like never before. He's amazed at how many neighbors and old friends from high school are coming out of the woodwork to ask him how clinical trials work. "What happens next is interesting. Does this open a window of opportunity to get more content out? People's appetites have been whetted."

High-profile wins could help to sustain interest, such as deployment of rapid tests of COVID-19 to be taken at home, a version of which the FDA authorized on November 18th. The idea bears resemblance to the Theranos concept, also designed as a portable analysis, except this test met the FDA's requirements and has a legitimate chance of changing people's lives. Meanwhile, at least two vaccines are on track to gain government approval in record time. The unprecedented speed could be a catalyst for streamlining inefficiencies in the FDA's approval process in non-emergency situations.

Tests for COVID-19 represent what some view as the future of managing diseases: early detection. This paradigm may be more feasible—and deserving of journalistic ink—than research on diseases in advanced stages, says Azra Raza, professor of medicine at Columbia University. "Journalists have to challenge this conceit of thinking we can cure end-stage cancer," says Raza, author of The First Cell. Beyond animal studies and "exercise helps" articles, she thinks writers should focus on biotech for catching the earliest footprints of cancer when it's more treatable. "Not enough people appreciate the extent of this tragedy, but journalists can help us do it. COVID-19 is a great moment of truth telling."

Another pressing truth is the need for vaccination, as half of Americans have said they'll skip them due to concerns about safety and effectiveness. It's not the kind of stumbling block faced by iPhones or social media algorithms. AI stirs plenty of its own controversy, but the public's interest in learning about AI and engaging with it seems to grow regardless. "Who are the publicists doing such a good job for AI that biotechnology is lacking?" Lipset wonders.

The job description of those publicists, whoever they are, could be expanding. Scientists are increasingly using AI to measure the effects of new medicines that target diseases—including COVID-19—and the pathways of aging. Mullin noted the challenge of reporting breakthroughs in the life sciences in ways the public understands. With many newsrooms tightening budgets, fewer writers have science backgrounds, and "biotech is daunting for journalists," she says. "It's daunting for me and I work in this area." Now factor in the additional expertise required to understand biotech and AI. "I learned the ropes for how to read a biotech paper, but I have no idea how to read an AI paper."

Nevertheless, Mullin believes reporters have a duty to scrutinize whether this convergence of AI and biotech will foster better outcomes. "Is it just the shiny new tool we're employing because we can? Will algorithms help eliminate health disparities or contribute to them even more? We need to pay attention."

Blood Money: Paying for Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19

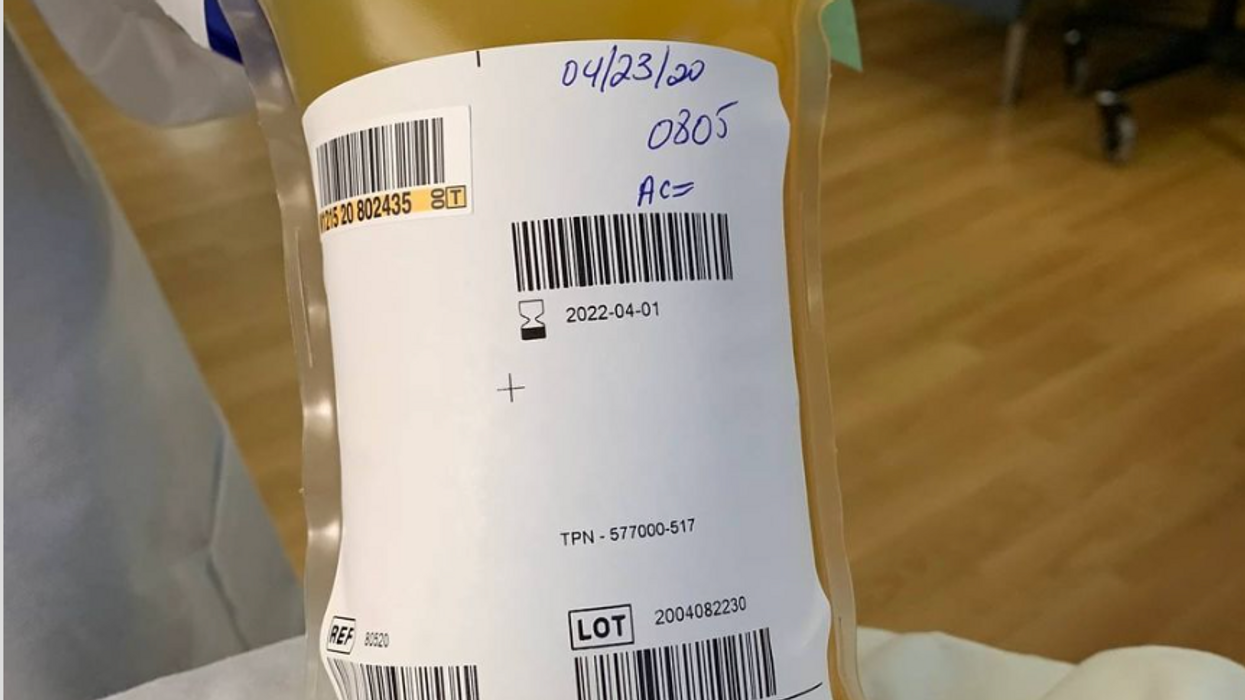

A bag of plasma that Tom Hanks donated back in April 2020 after his coronavirus infection. (He was not paid to donate.)

Convalescent plasma – first used to treat diphtheria in 1890 – has been dusted off the shelf to treat COVID-19. Does it work? Should we rely strictly on the altruism of donors or should people be paid for it?

The biologic theory is that a person who has recovered from a disease has chemicals in their blood, most likely antibodies, that contributed to their recovery, and transferring those to a person who is sick might aid their recovery. Whole blood won't work because there are too few antibodies in a single unit of blood and the body can hold only so much of it.

Plasma comprises about 55 percent of whole blood and is what's left once you take out the red blood cells that carry oxygen and the white blood cells of the immune system. Most of it is water but the rest is a complex mix of fats, salts, signaling molecules and proteins produced by the immune system, including antibodies.

A process called apheresis circulates the donors' blood through a machine that separates out the desired parts of blood and returns the rest to the donor. It takes several times the length of a regular whole blood donation to cycle through enough blood for the process. The end product is a yellowish concentration called convalescent plasma.

Recent History

It was used extensively during the great influenza epidemic off 1918 but fell out of favor with the development of antibiotics. Still, whenever a new disease emerges – SARS, MERS, Ebola, even antibiotic-resistant bacteria – doctors turn to convalescent plasma, often as a stopgap until more effective antibiotic and antiviral drugs are developed. The process is certainly safe when standard procedures for handling blood products are followed, and historically it does seem to be beneficial in at least some patients if administered early enough in the disease.

With few good treatment options for COVID-19, doctors have given convalescent plasma to more than a hundred thousand Americans and tens of thousand of people elsewhere, to mixed results. Placebo-controlled trials could give a clearer picture of plasma's value but it is difficult to enroll patients facing possible death when the flip of a coin will determine who will receive a saline solution or plasma.

And the plasma itself isn't some uniform pill stamped out in a factory, it's a natural product that is shaped by the immune history of the donor's body and its encounter not just with SARS-CoV-2 but a lifetime of exposure to different pathogens.

Researchers believe antibodies in plasma are a key factor in directly fighting the virus. But the variety and quantity of antibodies vary from donor to donor, and even over time from the same donor because once the immune system has cleared the virus from the body, it stops putting out antibodies to fight the virus. Often the quality and quantity of antibodies being given to a patient are not measured, making it somewhat hit or miss, which is why several companies have recently developed monoclonal antibodies, a single type of antibody found in blood that is effective against SARS-CoV-2 and that is multiplied in the lab for use as therapy.

Plasma may also contain other unknown factors that contribute to fighting disease, say perhaps signaling molecules that affect gene expression, which might affect the movement of immune cells, their production of antiviral molecules, or the regulation of inflammation. The complexity and lack of standardization makes it difficult to evaluate what might be working or not with a convalescent plasma treatment. Thus researchers are left with few clues about how to make it more effective.

Industrializing Plasma

Many Americans living along the border with Mexico regularly head south to purchase prescription drugs at a significant discount. Less known is the medical traffic the other way, Mexicans who regularly head north to be paid for plasma donations, which are prohibited in their country; the U.S. allows payment for plasma donations but not whole blood. A typical payment is about $35 for a donation but the sudden demand for convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19 commands a premium price, sometimes as high as $200. These donors are part of a fast-growing plasma industry that surpassed $25 billion in 2018. The U.S. supplies about three-quarters of the world's needs for plasma.

Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free.

The pharmaceutical industry has shied away from natural products they cannot patent but they have identified simpler components from plasma, such as clotting factors and immunoglobulins, that have been turned into useful drugs from this raw material of plasma. While some companies have retooled to provide convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19, often paying those donors who have recovered a premium of several times the normal rate, most convalescent plasma has come as donations through traditional blood centers.

In April the Mayo Clinic, in cooperation with the FDA, created an expanded access program for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. It was meant to reduce the paperwork associated with gaining access to a treatment not yet approved by the FDA for that disease. Initially it was supposed to be for 5000 units but it quickly grew to more than twenty times that size. Michael Joyner, the head of the program, discussed that experience in an extended interview in September.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also created associated reimbursement codes, which became permanent in August.

Mayo published an analysis of the first 35,000 patients as a preprint in August. It concluded, "The relationships between mortality and both time to plasma transfusion, and antibody levels provide a signature that is consistent with efficacy for the use of convalescent plasma in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients."

It seemed to work best when given early in infection and in larger doses; a similar pattern has been seen in studies of monoclonal antibodies. A revised version will soon be published in a major medical journal. Some criticized the findings as not being from a randomized clinical trial.

Convalescent plasma is not the only intervention that seems to work better when used earlier in the course of disease. Recently the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly stopped a clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody in hospitalized COVID-19 patients when it became apparent it wasn't helping. It is continuing trials for patients who are less sick and begin treatment earlier, as well as in persons who have been exposed to the virus but not yet diagnosed as infected, to see if it might prevent infection. In November the FDA eased access to this drug outside of clinical trials, though it is not yet approved for sale.

Show Me the Money

The antibodies that seem to give plasma its curative powers are fragile proteins that the body produces to fight the virus. Production shuts down once the virus is cleared and the remaining antibodies survive only for a few weeks before the levels fade. [Vaccines are used to train immune cells to produce antibodies and other defenses to respond to exposure to future pathogens.] So they can be usefully harvested from a recovered patient for only a few short weeks or months before they decline precipitously. The question becomes, how does one mobilize this resource in that short window of opportunity?

The program run by the Mayo Clinic explains the process and criteria for donating convalescent plasma for COVID-19, as well as links to local blood centers equipped to handle those free donations. Commercial plasma centers also are advertising and paying for donations.

A majority of countries prohibit paying donors for blood or blood products, including India. But an investigation by India Today touted a black market of people willing to donate convalescent plasma for the equivalent of several hundred dollars. Officials vowed to prosecute, saying donations should be selfless.

But that enforcement threat seemed to be undercut when the health minister of the state of Assam declared "plasma donors will get preference in several government schemes including the government job interview." It appeared to be a form of compensation that far surpassed simple cash.

The small city of Rexburg, Idaho, with a population a bit over 50,000, overwhelmingly Mormon and home to a campus of Brigham Young University, at one point had one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19 in the current wave of infection. Rumors circulated that some students were intentionally trying to become infected so they could later sell their plasma for top dollar, potentially as much as $200 a visit.

Troubled university officials investigated the allegations but could come up with nothing definitive; how does one prove intentionality with such an omnipresent yet elusive virus? They chalked it up to idle chatter, perhaps an urban legend, which might be associated with alcohol use on some other campus.

Doctors, hospitals, and drug companies are all rightly praised for their altruism in the fight against COVID-19, but they also get paid. Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free. "Why do we expect the donors [of convalescent plasma] to be the only uncompensated people in the process? It really makes no sense," argues Mark Yarborough, an ethicist at the UC Davis School of Medicine in Sacramento.

"When I was in grad school, two of my closest friends, at least once a week they went and gave plasma. That was their weekend spending money," Yarborough recalls. He says upper and middle-income people may have the luxury of donating blood products but prohibiting people from selling their plasma is a bit paternalistic and doesn't do anything to improve the economic status of poor people.

"Asking people to dedicate two hours a week for an entire year in exchange for cookies and milk is demonstrably asking too much," says Peter Jaworski, an ethicist who teaches at Georgetown University.

He notes that companies that pay plasma donors have much lower total costs than do operations that rely solely on uncompensated donations. The companies have to spend less to recruit and retain donors because they increase payments to encourage regular repeat donations. They are able to more rationally schedule visits to maximize use of expensive apheresis equipment and medical personnel used for the collection.

It seems that COVID-19 has been with us forever, but in reality it is less than a year. We have learned much over that short time, can now better manage the disease, and have lower mortality rates to prove it. Just how much convalescent plasma may have contributed to that remains an open question. Access to vaccines is months away for many people, and even then some people will continue to get sick. Given the lack of proven treatments, it makes sense to keep plasma as part of the mix, and not close the door to any legitimate means to obtain it.