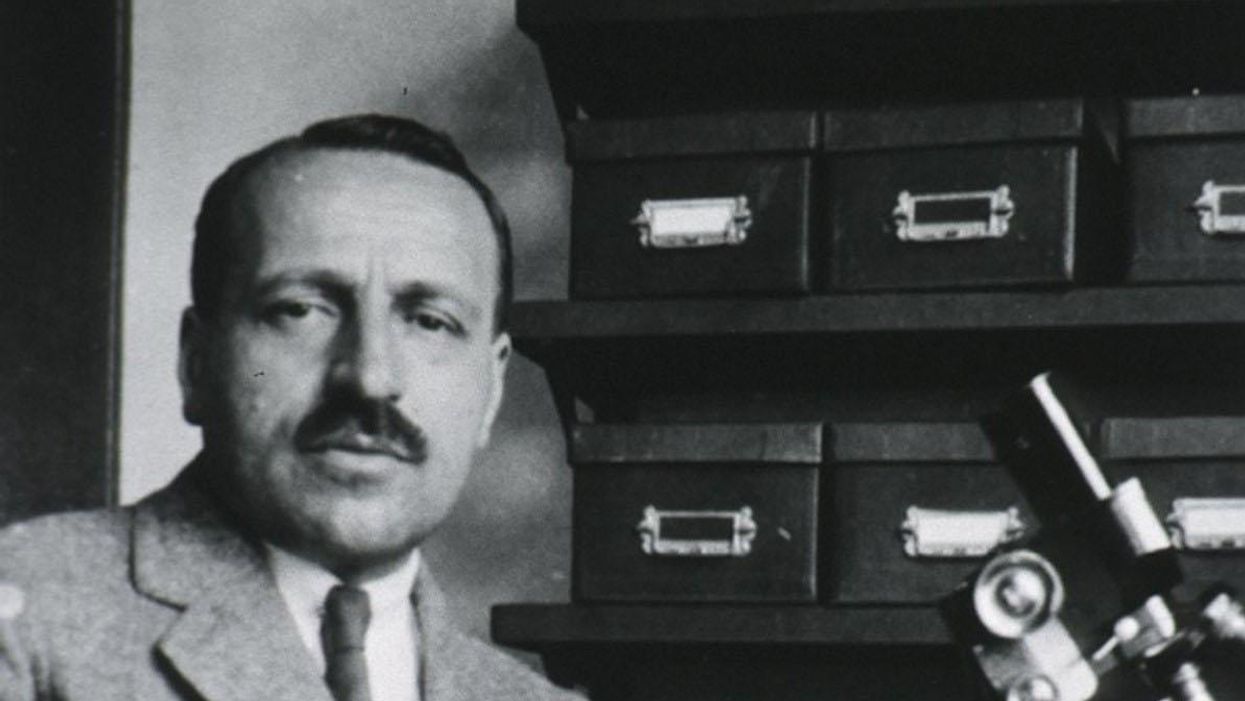

The Scientist Behind the Pap Smear Saved Countless Women from Cervical Cancer

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.

Dr. Steffanie Strathdee, an infectious disease epidemiologist, saved her husband Tom from a superbug infection by mobilizing scientists around the world to help him access experimental phage therapy.

[Editor's Note: This is the fifth episode in our Moonshot series, which explores cutting-edge scientific developments that stand to fundamentally transform our world.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

The latest tools, like whole genome sequencing, are allowing food outbreaks to be identified and stopped more quickly.

With the pandemic at the forefront of everyone's minds, many people have wondered if food could be a source of coronavirus transmission. Luckily, that "seems unlikely," according to the CDC, but foodborne illnesses do still sicken a whopping 48 million people per year.

Whole genome sequencing is like "going from an eight-bit image—maybe like what you would see in Minecraft—to a high definition image."

In normal times, when there isn't a historic global health crisis infecting millions and affecting the lives of billions, foodborne outbreaks are real and frightening, potentially deadly, and can cause widespread fear of particular foods. Think of Romaine lettuce spreading E. coli last year— an outbreak that infected more than 500 people and killed eight—or peanut butter spreading salmonella in 2008, which infected 167 people.

The technologies available to detect and prevent the next foodborne disease outbreak have improved greatly over the past 30-plus years, particularly during the past decade, and better, more nimble technologies are being developed, according to experts in government, academia, and private industry. The key to advancing detection of harmful foodborne pathogens, they say, is increasing speed and portability of detection, and the precision of that detection.

Getting to Rapid Results

Researchers at Purdue University have recently developed a lateral flow assay that, with the help of a laser, can detect toxins and pathogenic E. coli. Lateral flow assays are cheap and easy to use; a good example is a home pregnancy test. You place a liquid or liquefied sample on a piece of paper designed to detect a single substance and soon after you get the results in the form of a colored line: yes or no.

"They're a great portable tool for us for food contaminant detection," says Carmen Gondhalekar, a fifth-year biomedical engineering graduate student at Purdue. "But one of the areas where paper-based lateral flow assays could use improvement is in multiplexing capability and their sensitivity."

J. Paul Robinson, a professor in Purdue's Colleges of Veterinary Medicine and Engineering, and Gondhalekar's advisor, agrees. "One of the fundamental problems that we have in detection is that it is hard to identify pathogens in complex samples," he says.

When it comes to foodborne disease outbreaks, you don't always know what substance you're looking for, so an assay made to detect only a single substance isn't always effective. The goal of the project at Purdue is to make assays that can detect multiple substances at once.

These assays would be more complex than a pregnancy test. As detailed in Gondhalekar's recent paper, a laser pulse helps create a spectral signal from the sample on the assay paper, and the spectral signal is then used to determine if any unique wavelengths associated with one of several toxins or pathogens are present in the sample. Though the handheld technology has yet to be built, the idea is that the results would be given on the spot. So someone in the field trying to track the source of a Salmonella infection could, for instance, put a suspected lettuce sample on the assay and see if it has the pathogen on it.

"What our technology is designed to do is to give you a rapid assessment of the sample," says Robinson. "The goal here is speed."

Seeing the Pathogen in "High-Def"

"One in six Americans will get a foodborne illness every year," according to Dr. Heather Carleton, a microbiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Enteric Diseases Laboratory Branch. But not every foodborne outbreak makes the news. In 2017 alone, the CDC monitored between 18 and 37 foodborne poison clusters per week and investigated 200 multi-state clusters. Hardboiled eggs, ground beef, chopped salad kits, raw oysters, frozen tuna, and pre-cut melon are just a taste of the foods that were investigated last year for different strains of listeria, salmonella, and E. coli.

At the heart of the CDC investigations is PulseNet, a national network of laboratories that uses DNA fingerprinting to detect outbreaks at local and regional levels. This is how it works: When a patient gets sick—with symptoms like vomiting and fever, for instance—they will go to a hospital or clinic for treatment. Since we're talking about foodborne illnesses, a clinician will likely take a stool sample from the patient and send it off to a laboratory to see if there is a foodborne pathogen, like salmonella, E. Coli, or another one. If it does contain a potentially harmful pathogen, then a bacterial isolate of that identified sample is sent to a regional public health lab so that whole genome sequencing can be performed.

Whole genome sequencing can differentiate "virtually all" strains of foodborne pathogens, no matter the species, according to the FDA.

Whole genome sequencing is a method for reading the entire genome of a bacterial isolate (or from any organism, for that matter). Instead of working with a couple dozen data points, now you're working with millions of base pairs. Carleton likes to describe it as "going from an eight-bit image—maybe like what you would see in Minecraft—to a high definition image," she says. "It's really an evolution of how we detect foodborne illnesses and identify outbreaks."

If the bacterial isolate matches another in the CDC's database, this means there could be a potential outbreak and an investigation may be started, with the goal of tracking the pathogen to its source.

Whole genome sequencing has been a relatively recent shift in foodborne disease detection. For more than 20 years, the standard technique for analyzing pathogens in foodborne disease outbreaks was pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. This method creates a DNA fingerprint for each sample in the form of a pattern of about 15-30 "bands," with each band representing a piece of DNA. Researchers like Carleton can use this fingerprint to see if two samples are from the same bacteria. The problem is that 15-30 bands are not enough to differentiate all isolates. Some isolates whose bands look very similar may actually come from different sources and some whose bands look different may be from the same source. But if you can see the entire DNA fingerprint, then you don't have that issue. That's where whole genome sequencing comes in.

Although the PulseNet team had piloted whole genome sequencing as early as 2013, it wasn't until July of last year that the transition to using whole genome sequencing for all pathogens was complete. Though whole genome sequencing requires far more computing power to generate, analyze, and compare those millions of data points, the payoff is huge.

Stopping Outbreaks Sooner

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acquired their first whole genome sequencers in 2008, according to Dr. Eric Brown, the Director of the Division of Microbiology in the FDA's Office of Regulatory Science. Since then, through their GenomeTrakr program, a network of more than 60 domestic and international labs, the FDA has sequenced and publicly shared more than 400,000 isolates. "The impact of what whole genome sequencing could do to resolve a foodborne outbreak event was no less impactful than when NASA turned on the Hubble Telescope for the first time," says Brown.

Whole genome sequencing has helped identify strains of Salmonella that prior methods were unable to differentiate. In fact, whole genome sequencing can differentiate "virtually all" strains of foodborne pathogens, no matter the species, according to the FDA. This means it takes fewer clinical cases—fewer sick people—to detect and end an outbreak.

And perhaps the largest benefit of whole genome sequencing is that these detailed sequences—the millions of base pairs—can imply geographic location. The genomic information of bacterial strains can be different depending on the area of the country, helping these public health agencies eventually track the source of outbreaks—a restaurant, a farm, a food-processing center.

Coming Soon: "Lab in a Backpack"

Now that whole genome sequencing has become the go-to technology of choice for analyzing foodborne pathogens, the next step is making the process nimbler and more portable. Putting "the lab in a backpack," as Brown says.

The CDC's Carleton agrees. "Right now, the sequencer we use is a fairly big box that weighs about 60 pounds," she says. "We can't take it into the field."

A company called Oxford Nanopore Technologies is developing handheld sequencers. Their devices are meant to "enable the sequencing of anything by anyone anywhere," according to Dan Turner, the VP of Applications at Oxford Nanopore.

"The sooner that we can see linkages…the sooner the FDA gets in action to mitigate the problem and put in some kind of preventative control."

"Right now, sequencing is very much something that is done by people in white coats in laboratories that are set up for that purpose," says Turner. Oxford Nanopore would like to create a new, democratized paradigm.

The FDA is currently testing these types of portable sequencers. "We're very excited about it. We've done some pilots, to be able to do that sequencing in the field. To actually do it at a pond, at a river, at a canal. To do it on site right there," says Brown. "This, of course, is huge because it means we can have real-time sequencing capability to stay in step with an actual laboratory investigation in the field."

"The timeliness of this information is critical," says Marc Allard, a senior biomedical research officer and Brown's colleague at the FDA. "The sooner that we can see linkages…the sooner the FDA gets in action to mitigate the problem and put in some kind of preventative control."

At the moment, the world is rightly focused on COVID-19. But as the danger of one virus subsides, it's only a matter of time before another pathogen strikes. Hopefully, with new and advancing technology like whole genome sequencing, we can stop the next deadly outbreak before it really gets going.