The Scientist Behind the Pap Smear Saved Countless Women from Cervical Cancer

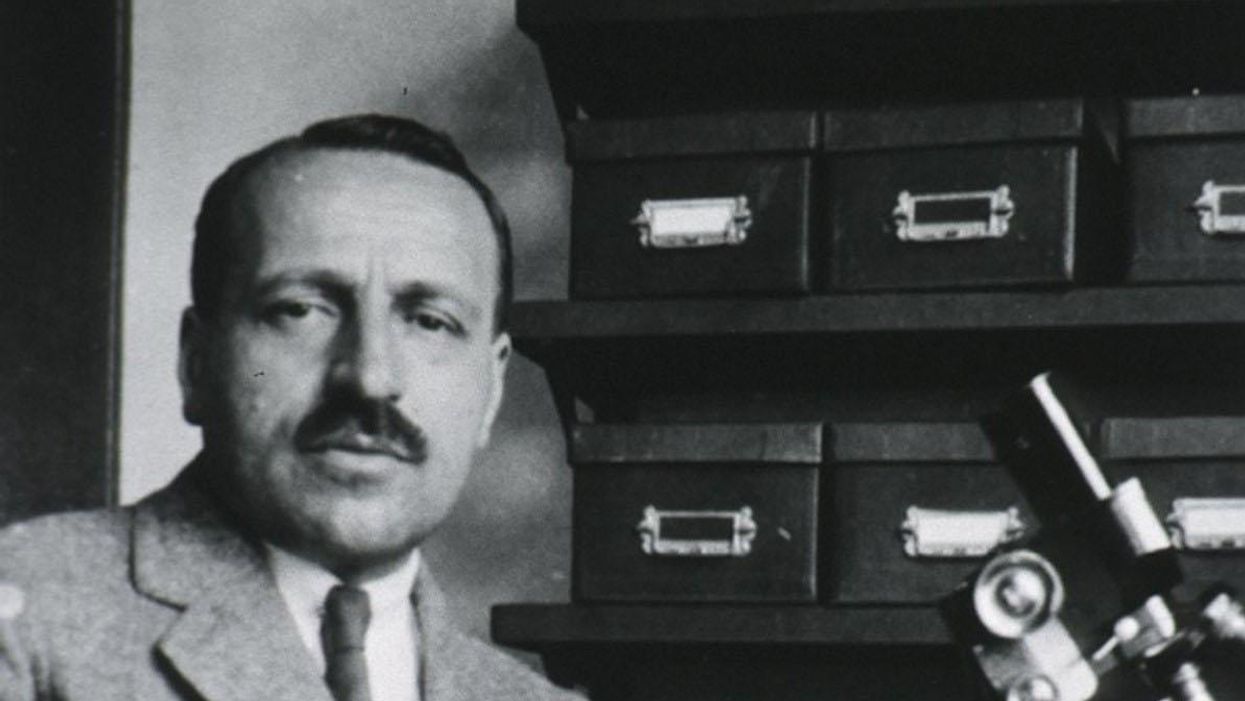

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.

Harvard Researchers Are Using a Breakthrough Tool to Find the Antibodies That Best Knock Out the Coronavirus

Knowing which antibodies bind best to the coronavirus can help guide new medicines and vaccine development.

To find a cure for a deadly infectious disease in the 1995 medical thriller Outbreak, scientists extract the virus's antibodies from its original host—an African monkey.

"When a person is infected, the immune system makes antibodies kind of blindly."

The antibodies prevent the monkeys from getting sick, so doctors use these antibodies to make the therapeutic serum for humans. With SARS-CoV-2, the original hosts might be bats or pangolins, but scientists don't have access to either, so they are turning to the humans who beat the virus.

Patients who recovered from COVID-19 are valuable reservoirs of viral antibodies and may help scientists develop efficient therapeutics, says Stephen J. Elledge, professor of genetics and medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Studying the structure of the antibodies floating in their blood can help understand what their immune systems did right to kill the pathogen.

When viruses invade the body, the immune system builds antibodies against them. The antibodies work like Velcro strips—they use special spots on their surface called paratopes to cling to the specific spots on the viral shell called epitopes. Once the antibodies circulating in the blood find their "match," they cling on to the virus and deactivate it.

But that process is far from simple. The epitopes and paratopes are built of various peptides that have complex shapes, are folded in specific ways, and may carry an electrical charge that repels certain molecules. Only when all of these parameters match, an antibody can get close enough to a viral particle—and shut it out.

So the immune system forges many different antibodies with varied parameters in hopes that some will work. "When a person is infected, the immune system makes antibodies kind of blindly," Elledge says. "It's doing a shotgun approach. It's not sure which ones will work, but it knows once it's made a good one that works."

Elledge and his team want to take the guessing out of the process. They are using their home-built tool VirScan to comb through the blood samples of the recovered COVID-19 patients to see what parameters the efficient antibodies should have. First developed in 2015, the VirScan has a library of epitopes found on the shells of viruses known to afflict humans, akin to a database of criminals' mug shots maintained by the police.

Originally, VirScan was meant to reveal which pathogens a person overcame throughout a lifetime, and could identify over 1,000 different strains of viruses and bacteria. When the team ran blood samples against the VirScan's library, the tool would pick out all the "usual suspects." And unlike traditional blood tests called ELISA, which can only detect one pathogen at a time, VirScan can detect all of them at once. Now, the team has updated VirScan with the SARS-CoV-2 "mug shot" and is beginning to test which antibodies from the recovered patients' blood will bind to them.

Knowing which antibodies bind best can also help fine-tune vaccines.

Obtaining blood samples was a challenge that caused some delays. "So far most of the recovered patients have been in China and those samples are hard to get," Elledge says. It also takes a person five to 10 days to develop antibodies, so the blood must be drawn at the right time during the illness. If a person is asymptomatic, it's hard to pinpoint the right moment. "We just got a couple of blood samples so we are testing now," he said. The team hopes to get some results very soon.

Elucidating the structure of efficient antibodies can help create therapeutics for COVID-19. "VirScan is a powerful technology to study antibody responses," says Harvard Medical School professor Dan Barouch, who also directs the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research. "A detailed understanding of the antibody responses to COVID-19 will help guide the design of next-generation vaccines and therapeutics."

For example, scientists can synthesize antibodies to specs and give them to patients as medicine. Once vaccines are designed, medics can use VirScan to see if those vaccinated again COVID-19 generate the necessary antibodies.

Knowing which antibodies bind best can also help fine-tune vaccines. Sometimes, viruses cause the immune system to generate antibodies that don't deactivate it. "We think the virus is trying to confuse the immune system; it is its business plan," Elledge says—so those unhelpful antibodies shouldn't be included in vaccines.

More importantly, VirScan can also tell which people have developed immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and can return to their workplaces and businesses, which is crucial to restoring the economy. Knowing one's immunity status is especially important for doctors working on the frontlines, Elledge notes. "The resistant ones can intubate the sick."

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Defenders of civil liberties fear that the erosion of privacy will become a long-term consequence of the pandemic.

As countries around the world combat the coronavirus outbreak, governments that already operated sophisticated surveillance programs are ramping up the tracking of their citizens.

"The potential for invasions of privacy, abuse, and stigmatization is enormous."

Countries like China, South Korea, Israel, Singapore and others are closely monitoring citizens to track the spread of the virus and prevent further infections, and policymakers in the United States have proposed similar steps. These shifts in policy have civil liberties defenders alarmed, as history has shown increases in surveillance tend to stick around after an emergency is over.

In China, where the virus originated and surveillance is already ubiquitous, the government has taken measures like having people scan a QR code and answer questions about their health and travel history to enter their apartment building. The country has also increased the tracking of cell phones, encouraged citizens to report people who appear to be sick, utilized surveillance drones, and developed facial recognition that can identify someone even if they're wearing a mask.

In Israel, the government has begun tracking people's cell phones without a court order under a program that was initially meant to counter terrorism. Singapore has also been closely tracking people's movements using cell phone data. In South Korea, the government has been monitoring citizens' credit card and cell phone data and has heavily utilized facial recognition to combat the spread of the coronavirus.

Here at home, the United States government and state governments have been using cell phone data to determine where people are congregating. White House senior adviser Jared Kushner's task force to combat the coronavirus outbreak has proposed using cell phone data to track coronavirus patients. Cities around the nation are also using surveillance drones to maintain social distancing orders. Companies like Apple and Google that work closely with the federal government are currently developing systems to track Americans' cell phones.

All of this might sound acceptable if you're worried about containing the outbreak and getting back to normal life, but as we saw when the Patriot Act was passed in 2001 in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, expansions of the surveillance state can persist long after the emergency that seemed to justify them.

Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst with the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, says that this public health emergency requires bold action, but he worries that actions may be taken that will infringe on our privacy rights.

"This is an extraordinary crisis that justifies things that would not be justified in ordinary times, but we, of course, worry that any such things would be made permanent," Stanley says.

Stanley notes that the 9/11 situation was different from this current situation because we still face the threat of terrorism today, and we always will. The Patriot Act was a response to that threat, even if it was an extreme response. With this pandemic, it's quite possible we won't face something like this again for some time.

"We know that for the last seven or eight decades, we haven't seen a microbe this dangerous become a pandemic, and it's reasonable to expect it's not going to be happening for a while afterward," Stanley says. "We do know that when a vaccine is produced and is produced widely enough, the COVID crisis will be over. This does, unlike 9/11, have a definitive ending."

The ACLU released a white paper last week outlining the problems with using location data from cell phones and how policymakers should proceed when they discuss the usage of surveillance to combat the outbreak.

"Location data contains an enormously invasive and personal set of information about each of us, with the potential to reveal such things as people's social, sexual, religious, and political associations," they wrote. "The potential for invasions of privacy, abuse, and stigmatization is enormous. Any uses of such data should be temporary, restricted to public health agencies and purposes, and should make the greatest possible use of available techniques that allow for privacy and anonymity to be protected, even as the data is used."

"The first thing you need to combat pervasive surveillance is to know that it's occurring."

Sara Collins, policy counsel at the digital rights organization Public Knowledge, says that one of the problems with the current administration is that there's not much transparency, so she worries surveillance could be increased without the public realizing it.

"You'll often see the White House come out with something—that they're going to take this action or an agency just says they're going to take this action—and there's no congressional authorization," Collins says. "There's no regulation. There's nothing there for the public discourse."

Collins says it's almost impossible to protect against infringements on people's privacy rights if you don't actually know what kind of surveillance is being done and at what scale.

"I think that's very concerning when there's no accountability and no way to understand what's actually happening," Collins says. "The first thing you need to combat pervasive surveillance is to know that it's occurring."

We should also be worried about corporate surveillance, Collins says, because the tech companies that keep track of our data work closely with the government and do not have a good track record when it comes to protecting people's privacy. She suspects these companies could use the coronavirus outbreak to defend the kind of data collection they've been engaging in for years.

Collins stresses that any increase in surveillance should be transparent and short-lived, and that there should be a limit on how long people's data can be kept. Otherwise, she says, we're risking an indefinite infringement on privacy rights. Her organization will be keeping tabs as the crisis progresses.

It's not that we shouldn't avail ourselves of modern technology to fight the pandemic. Indeed, once lockdown restrictions are gradually lifted, public health officials must increase their ability to isolate new cases and trace, test, and quarantine contacts.

But tracking the entire populace "Big Brother"-style is not the ideal way out of the crisis. Last week, for instance, a group of policy experts -- including former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb -- published recommendations for how to achieve containment. They emphasized the need for widespread diagnostic and serologic testing as well as rapid case-based interventions, among other measures -- and they, too, were wary of pervasive measures to follow citizens.

The group wrote: "Improved capacity [for timely contact tracing] will be most effective if coordinated with health care providers, health systems, and health plans and supported by timely electronic data sharing. Cell phone-based apps recording proximity events between individuals are unlikely to have adequate discriminating ability or adoption to achieve public health utility, while introducing serious privacy, security, and logistical concerns."

The bottom line: Any broad increases in surveillance should be carefully considered before we go along with them out of fear. The Founders knew that privacy is integral to freedom; that's why they wrote the Fourth Amendment to protect it, and that right shouldn't be thrown away because we're in an emergency. Once you lose a right, you don't tend to get it back.