People With This Rare Disease Can Barely Eat Protein. Biotechnology May Change That.

The Brown family at the Grand Tetons (2019). Clockwise from left, Christine, Kevin, Keagan, Connor, and Kellen.

Imagine that the protein in bread, eggs, steak, even beans is not the foundation for a healthy diet, but a poison to your brain. That is the reality for people living with Phenylketonuria, or PKU. This cluster of rare genetic variations affects the ability to digest phenylalanine (Phe), one of the chemical building blocks of protein. The toxins can build up in the brain causing severe mental retardation.

Can a probiotic help digest the troublesome proteins before they can enter the bloodstream and travel to the brain? A Boston area biotech start up, Synlogic, believes it can. Their starting point is an E. coli bacterium that has been used as a probiotic for more than a century. The company then screened thousands of gene variants to identify ones that produced enzymes most efficient at slicing and dicing the target proteins and optimized them further through directed evolution. The results have been encouraging.

But Christine Brown knew none of this when the hospital called saying that standard newborn screening of her son Connor had come back positive for PKU. It was urgent that they visit a special metabolic clinic the next day, which was about a three-hour drive away.

“I was told not to go on the Internet,” Christine recalls, “So when somebody tells you not to go on the Internet, what do you do? Even back in 2005, right.” What she saw were the worst examples of retardation, which was a common outcome from PKU before newborn screening became routine. “We were just in complete shell shock, our whole world just kind of shattered and went into a tail spin.”

“I remember feeding him the night before our clinic visit and almost feeling like I was feeding him poison because I knew that breast milk must have protein in it,” she says.

“Some of my first memories are of asking, ‘Mommy, can I eat this? There were yes foods and no foods.'"

Over the next few days the dedicated staff of the metabolic clinic at the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin Madison began to walk she and husband Kevin back from that nightmare. They learned that a simple blood test to screen newborns had been developed in the early 1960s to detect PKU and that the condition could be managed with stringent food restrictions and vigilant monitoring of Phe levels.

Everything in Your Mouth Counts

PKU can be successfully managed with a severely restricted diet. That simple statement is factually true, but practically impossible to follow, as it requires slashing protein consumption by about 90 percent. To compensate for the missing protein, several times a day PKU patients take a medical formula – commonly referred to simply as formula – containing forms of proteins that are digestible to their bodies. Several manufacturers now add vitamins and minerals and offer a variety of formats and tastes to make it more consumer friendly, but that wasn't always the case.

“When I was a kid, it tasted horrible, was the consistency of house paint. I didn't think about it, I just drank it. I didn't like it but you get used to it after a while,” recalls Jeff Wolf, the twang of Appalachia still strong in his voice. Now age 50, he grew up in Ashland, Kentucky and was part of the first wave of persons with PKU who were identified at birth as newborn screening was rolled out across the US. He says the options of taste and consistency have improved tremendously over the years.

Some people with PKU are restricted to as little as 8 grams of protein a day from food. That's a handful of almonds or a single hard-boiled egg; a skimpy 4-ounce hamburger and slice of cheese adds up to half of their weekly protein ration. Anything above that daily allowance is more than the body can handle and toxic levels of Phe begin to accumulate in the brain.

“Some of my first memories are of asking, ‘Mommy, can I eat this? There were yes foods and no foods,’” recalls Les Clark. He has never eaten a hamburger, steak, or ribs, practically a sacrilege for someone raised in Stanton, a small town in northeastern Nebraska, a state where the number of cattle and hogs are several-fold those of people.

His grandmother learned how to make low protein bread, but it looked and tasted different. His mom struggled making birthday cakes. “I learned some bad words at a very young age” as mom struggled applying icing that would pull the cake apart or a slice would collapse into a heap of crumbs, Les recalls.

Les Clark with a birthday cake.

Courtesy Clark

Controlling the diet “is not so bad when you are a baby” because that's all you know, says Jerry Vockley, Director of the Center for Rare Disease Therapy at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh. “But after a while, as you get older and you start tasting other things and you say, Well, gee, this stuff tastes way better than what you're giving me. What's the deal? It becomes harder to maintain the diet.”

First is the lure of forbidden foods as children venture into the community away from the watchful eyes of parents. The support system weakens further when they leave home for college or work. “Pizza was mighty tasty,” Wolf' says of his first slice.

Vockley estimates that about 90 percent of adults with PKU are off of treatment. Moving might mean finding a new metabolic clinic that treats PKU. A lapse in insurance coverage can be a factor. Finally there is plain fatigue from multiple daily dosing of barely tolerable formula, monitoring protein intake, and simply being different in terms of food restrictions. Most people want to fit in and not be defined by their medical condition.

Jeff Wolf was one of those who dropped out in his twenties and thirties. He stopped going to clinic, monitoring his Phe levels, and counting protein. But the earlier experience of living with PKU never completely left the back of his mind; he listened to his body whenever eating too much protein left him with the “fuzzy brain" of a protein hangover. About a decade ago he reconnected with a metabolic clinic, began taking formula and watching his protein intake. He still may go over his allotment for a single day but he tries to compensate on subsequent days so that his Phe levels come back into balance.

Jeff Wolf on a boat.

Courtesy Wolf

One of the trickiest parts of trying to manage phenylalanine intake is the artificial sweetener aspartame. The chemical is ubiquitous in diet and lite foods and drinks. Gum too, you don't even have to swallow to receive a toxic dose of Phe. Most PKUers say it is easier to simply avoid these products entirely rather than try to count their Phe content.

Treatments

Most rare diseases have no treatment. There are two drugs for PKU that provide some benefit to some portion of patients but those drugs often have their own burdens.

KUVAN® (sapropterin dihydrochloride) is a pill or powder that helps correct a protein folding error so that food proteins can be digested. It is approved for most types of PKU in adults and children one month and older, and often is used along with a protein-restricted diet.

“The problem is that it doesn't work for every [patient's genetic] mutation, and there are hundreds of mutations that have been identified with PKU. Two to three percent of patients will have a very dramatic response and if you're one of those small number of patients, it's great,” says Vockley. “If you have one of the other mutation, chances are pretty good you still are going to end up on a restricted diet.”

PALYNZIQ® (pegvaliase-pqpz) “has the potential to lower the Phe to normal levels, it's a real breakthrough in the field,” says Vockley. “But is a very hard drug to use. Most folks have to take either one or two 2ml injections a day of something that is basically a gel, and some individuals have to take three.”

Many PKUers have reactions at the site of the injection and some develop anaphylaxis, a severe potentially life-threatening allergic reaction that can happen within seconds and can occur at any time, even after long term use. Many patients using Palynziq carry an EpiPen, a self-injection devise containing a form of adrenaline that can reverse some of the symptoms of anaphylaxis.

Then there is the cost. With the Kuvan dosing for an adult, “you're talking between $100,000 and $200,000 a year. And Palynziq is three times that,” says Vockley. Insurance coverage through a private plan or a state program is essential. Some state programs provide generous coverage while others are skimpy. Most large insurance company plans cover the drugs, sometimes with significant copays, but companies that are self-insured are under no legal obligation to provide coverage.

Les Clark found that out the hard way when the company he worked for was sold. The new owner was self-insured and declined to continue covering his drugs. Almost immediately he was out of pocket an additional $1500 a month for formula, and that was with a substantial discount through the manufacturer's patient support program. He says, “If you don't have an insurance policy that will cover the formula, it's completely unaffordable.” He quickly began to look for a new job.

Hope

It's easy to see why PKUers are eager for advances that will make managing their condition more effect, easier, and perhaps more affordable. Synlogic's efforts have drawn their attention and raised hopes.

Just before Thanksgiving Jerry Vockley presented the latest data to a metabolism conference meeting in Australia. There were only 8 patients in this group of a phase 2 trial using the original version of the company's lead E. coli product, SYNB1618, but they were intensely studied. Each was given the probiotic and then a challenge meal. Vockley saw a 40% reduction in Phe absorption and later a 20% reduction in mean fasting Phe levels in the blood. The product was easy to use and tolerate.

The company also presented early results for SYNB1934, a follow on version that further genetically tweaked the E. coli to roughly double the capacity to chop up the target proteins. Synlogic is recruiting patients for studies to determine the best dosing, which they are planning for next year.

“It's an exciting approach,” says Lex Cowsert, Director of Research Development at the National PKU Alliance, a nonprofit that supports the patient, family, and research communities involved with PKU. “Every patient is different, every patient has a different tolerance for the type of therapy that they are willing to pursue,” and if it pans out, it will be a welcome addition, either alone or in combination with other approaches, to living with PKU.

Author's Note: Reporting this story was made possible by generous support from the National Press Foundation and the Fondation Ipsen. Thanks to the people who so generously shared their time and stories in speaking with me.

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

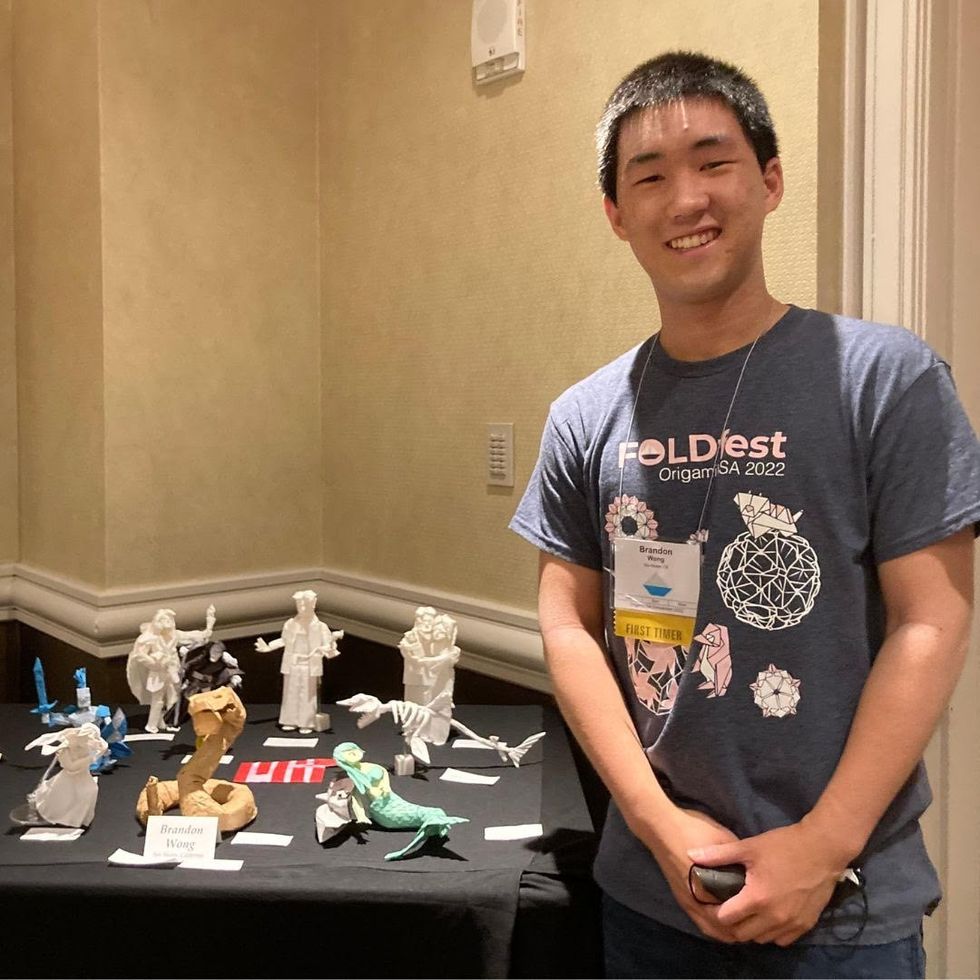

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”