Tapping into the Power of the Placebo Effect

When Wayne Jonas was in medical school 40 years ago, doctors would write out a prescription for placebos, spelling it out backwards in capital letters, O-B-E-C-A-L-P. The pharmacist would fill the prescription with a sugar pill, recalls Jonas, now director of integrative health programs at the Samueli Foundation. It fulfilled the patient's desire for the doctor to do something when perhaps no drug could help, and the sugar pills did no harm.

Today, that deception is seen as unethical. But time and time again, studies have shown that placebos can have real benefits. Now, researchers are trying to untangle the mysteries of placebo effect in an effort to better treat patients.

The use of placebos took off in the post-WWII period, when randomized controlled clinical trials became the gold standard for medical research. One group in a study would be treated with a placebo, a supposedly inert pill or procedure that would not affect normal healing and recovery, while another group in the study would receive an "active" component, most commonly a pill under investigation. Presumably, the group receiving the active treatment would have a better response and the difference from the placebo group would represent the efficacy of the drug being tested. That was the basis for drug approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

"Placebo responses were marginalized," says Ted Kaptchuk, director of the Program in Placebo Studies & Therapeutic Encounters at Harvard Medical School. "Doctors were taught they have to overcome it when they were thinking about using an effective drug."

But that began to change around the turn of the 21st century. The National Institutes of Health held a series of meetings to set a research agenda and fund studies to answer some basic questions, led by Jonas who was in charge of the office of alternative medicine at the time. "People spontaneously get better all the time," says Kaptchuk. The crucial question was, is the placebo effect real? Is it more than just spontaneous healing?

Brain mechanisms

A turning point came in 2001 in a paper in Science that showed physical evidence of the placebo effect. It used positron emission tomography (PET) scans to measure release patterns of dopamine — a chemical messenger involved in how we feel pleasure — in the brains of patients with Parkinson's disease. Surprisingly, the placebo activated the same patterns that were activated by Parkinson's drugs, such as levodopa. It proved the placebo effect was real; now the search was on to better understand and control it.

A key part of the effect can be the beliefs, expectations, context, and "rituals" of the encounter between doctor and patient. Belief by the doctor and patient that the treatment would work, and the formalized practices of administering the treatment can all contribute to a positive outcome.

Conditioning can be another important component in generating a response, as Pavlov demonstrated more than a century ago in his experiments with dogs. They were trained with a bell prior to feeding such that they would begin to salivate in anticipation at the sound of a bell even with no food present.

Translating that to humans, studies with pain medications and sleeping aids showed that patients who had a positive response with a certain dose of those medications could have the same response if the doses was reduced and a dummy pill substituted, even to the point where there was no longer any active ingredient.

Researchers think placebo treatments can work particularly well in helping people deal with pain and psychological disorders.

Those types of studies troubled Kaptchuk because they often relied on deception; patients weren't told they were receiving a placebo, or at best there was a possibility that they might be randomized to receive a placebo. He believed the placebo effect could work even if patients were told upfront that they were going to receive a placebo. More than a dozen so call "open-label placebo" studies across numerous medical conditions, by Kaptchuk and others, have shown that you don't have to lie to patients for a placebo to work.

Jonas likes to tell the story of a patient who used methotrexate, a potent immunosuppressant, to control her rheumatoid arthritis. She was planning a long trip and didn't want to be bothered with the injections and monitoring required in using the drug, So she began to drink a powerful herbal extract of anise, a licorice flavor that she hated, prior to each injection. She reduced the amount of methotrexate over a period of months and finally stopped, but continued to drink the anise. That process had conditioned her body "to alter her immune function and her autoimmunity" as if she were taking the drug, much like Pavlov's dogs had been trained. She has not taken methotrexate for more than a year.

An intriguing paper published in May 2021 found that mild, non-invasive electric stimulation to the brain could not only boost the placebo effect on pain but also reduce the "nocebo" effect — when patients report a negative effect to a sham treatment. While the work is very preliminary, it may open the door to directly manipulating these responses.

Researchers think placebo treatments can work particularly well in helping people deal with pain and psychological disorders, areas where drugs often are of little help. Still, placebos aren't a cure and only a portion of patients experience a placebo effect.

Nocebo

If medicine were a soap opera, the nocebo would be the evil twin of the placebo. It's what happens when patients have adverse side effects because of the expectation that they will. It's commonly seem when patients claims to experience pain or gastric distress that can occur with a drug even when they've received a placebo. The side effects were either imagined or caused by something else.

"Up to 97% of reported pharmaceutical side effects are not caused by the drug itself but rather by nocebo effects and symptom misattribution," according to one 2019 paper.

One way to reduce a nocebo response is to simply not tell patients that specific side effects might occur. An example is a liver biopsy, in which a large-gauge needle is used to extract a tissue sample for examination. Those told ahead of time that they might experience some pain were more likely to report pain and greater pain than those who weren't offered this information.

Interestingly, a nocebo response plays out in the hippocampus, a part of the brain that is never activated in a placebo response. "I think what we are dealing with with nocebo is anxiety," says Kaptchuk, but he acknowledges that others disagree.

Distraction may be another way to minimize the nocebo effect. Pediatricians are using virtual reality (VR) to engage children and distract them during routine procedures such as blood draws and changing wound dressings, and burn patients of all ages have found relief with specially created VRs.

Treatment response

Jonas argues that what we commonly call the placebo effect is misnamed and leading us astray. "The fact is people heal and that inherent healing capacity is both powerful and influenced by mental, social, and contextual factors that are embedded in every medical encounter since the idea of treatment began," he wrote in a 2019 article in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry. "Our understanding of healing and ability to enhance it will be accelerated if we stop using the term 'placebo response' and call it what it is—the meaning response, and its special application in medicine called the healing response."

He cites evidence that "only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care. The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life."

To better align treatments and maximize their effectiveness, Jonas has created HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note, "a patient-guided process designed to identify the patient's values and goals in their life and for healing." Essentially, it seeks to make clear to both doctor and patient what the patient's goals are in seeking treatment. In an extreme example of terminal cancer, some patients may choose to extend life despite the often brutal treatments, while others might prefer to optimize quality of life in the remaining time that they have. It builds on practices already taught in medical schools. Jonas believes doctors and patients can use tools like these to maximize the treatment response and achieve better outcomes.

Much of the medical profession has been resistant to these approaches. Part of that is simply tradition and limited data on their effectiveness, but another very real factor is the billing process for how they are reimbursed. Jonas says a new medical billing code added this year gives doctors another way to be compensated for the extra time and effort that a more holistic approach to medicine may initially require. Other moves away from fee-for-service payments to bundling and payment for outcomes, and the integrated care provided by the Veterans Affairs, Kaiser Permanente and other groups offer longer term hope for the future of approaches that might enhance the healing response.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on July 7, 2021.

New elevators could lift up our access to space

A space elevator would be cheaper and cleaner than using rockets

Story by Big Think

When people first started exploring space in the 1960s, it cost upwards of $80,000 (adjusted for inflation) to put a single pound of payload into low-Earth orbit.

A major reason for this high cost was the need to build a new, expensive rocket for every launch. That really started to change when SpaceX began making cheap, reusable rockets, and today, the company is ferrying customer payloads to LEO at a price of just $1,300 per pound.

This is making space accessible to scientists, startups, and tourists who never could have afforded it previously, but the cheapest way to reach orbit might not be a rocket at all — it could be an elevator.

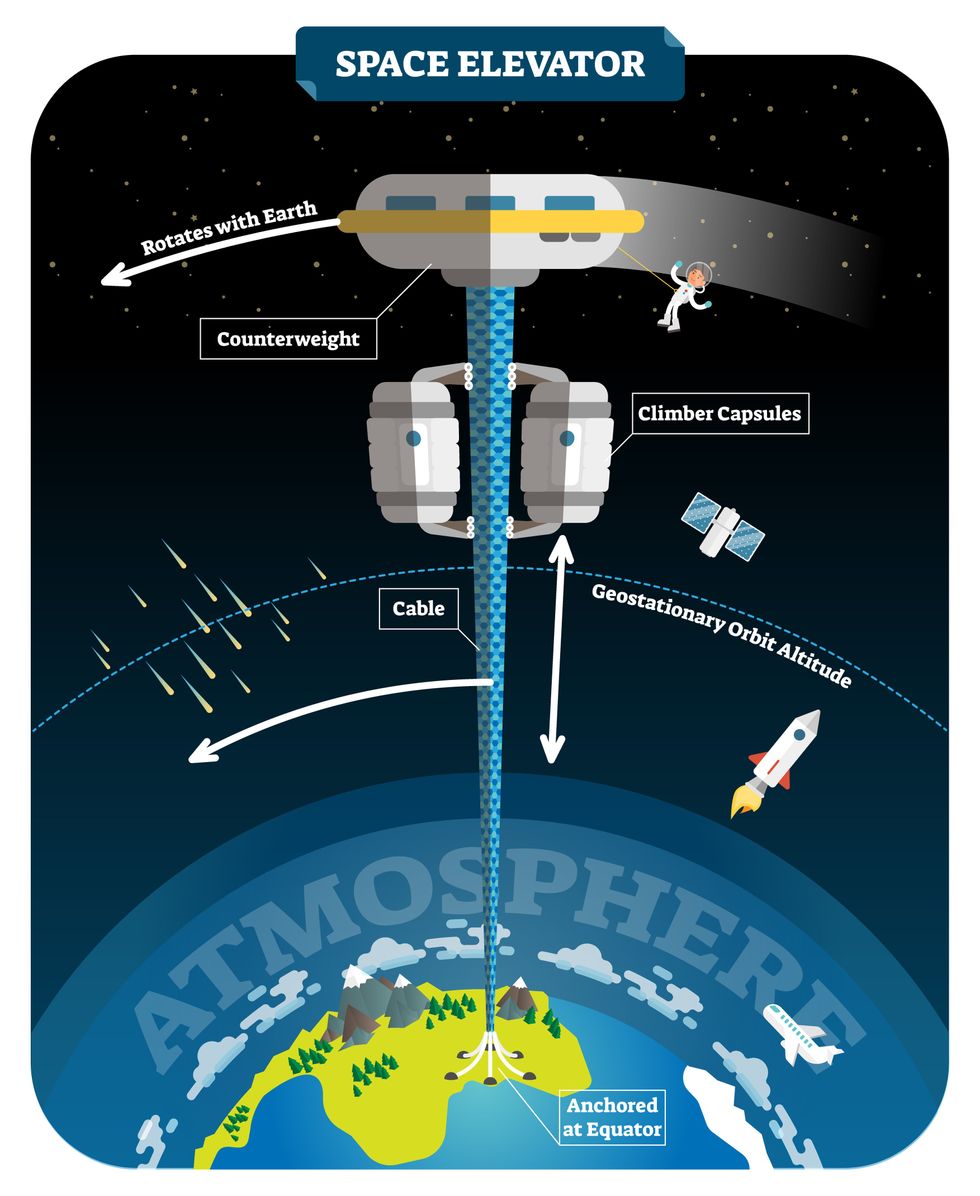

The space elevator

The seeds for a space elevator were first planted by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1895, who, after visiting the 1,000-foot (305 m) Eiffel Tower, published a paper theorizing about the construction of a structure 22,000 miles (35,400 km) high.

This would provide access to geostationary orbit, an altitude where objects appear to remain fixed above Earth’s surface, but Tsiolkovsky conceded that no material could support the weight of such a tower.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

In 1959, soon after Sputnik, Russian engineer Yuri N. Artsutanov proposed a way around this issue: instead of building a space elevator from the ground up, start at the top. More specifically, he suggested placing a satellite in geostationary orbit and dropping a tether from it down to Earth’s equator. As the tether descended, the satellite would ascend. Once attached to Earth’s surface, the tether would be kept taut, thanks to a combination of gravitational and centrifugal forces.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit. According to physicist Bradley Edwards, who researched the concept for NASA about 20 years ago, it’d cost $10 billion and take 15 years to build a space elevator, but once operational, the cost of sending a payload to any Earth orbit could be as low as $100 per pound.

“Once you reduce the cost to almost a Fed-Ex kind of level, it opens the doors to lots of people, lots of countries, and lots of companies to get involved in space,” Edwards told Space.com in 2005.

In addition to the economic advantages, a space elevator would also be cleaner than using rockets — there’d be no burning of fuel, no harmful greenhouse emissions — and the new transport system wouldn’t contribute to the problem of space junk to the same degree that expendable rockets do.

So, why don’t we have one yet?

Tether troubles

Edwards wrote in his report for NASA that all of the technology needed to build a space elevator already existed except the material needed to build the tether, which needs to be light but also strong enough to withstand all the huge forces acting upon it.

The good news, according to the report, was that the perfect material — ultra-strong, ultra-tiny “nanotubes” of carbon — would be available in just two years.

“[S]teel is not strong enough, neither is Kevlar, carbon fiber, spider silk, or any other material other than carbon nanotubes,” wrote Edwards. “Fortunately for us, carbon nanotube research is extremely hot right now, and it is progressing quickly to commercial production.”Unfortunately, he misjudged how hard it would be to synthesize carbon nanotubes — to date, no one has been able to grow one longer than 21 inches (53 cm).

Further research into the material revealed that it tends to fray under extreme stress, too, meaning even if we could manufacture carbon nanotubes at the lengths needed, they’d be at risk of snapping, not only destroying the space elevator, but threatening lives on Earth.

Looking ahead

Carbon nanotubes might have been the early frontrunner as the tether material for space elevators, but there are other options, including graphene, an essentially two-dimensional form of carbon that is already easier to scale up than nanotubes (though still not easy).

Contrary to Edwards’ report, Johns Hopkins University researchers Sean Sun and Dan Popescu say Kevlar fibers could work — we would just need to constantly repair the tether, the same way the human body constantly repairs its tendons.

“Using sensors and artificially intelligent software, it would be possible to model the whole tether mathematically so as to predict when, where, and how the fibers would break,” the researchers wrote in Aeon in 2018.

“When they did, speedy robotic climbers patrolling up and down the tether would replace them, adjusting the rate of maintenance and repair as needed — mimicking the sensitivity of biological processes,” they continued.Astronomers from the University of Cambridge and Columbia University also think Kevlar could work for a space elevator — if we built it from the moon, rather than Earth.

They call their concept the Spaceline, and the idea is that a tether attached to the moon’s surface could extend toward Earth’s geostationary orbit, held taut by the pull of our planet’s gravity. We could then use rockets to deliver payloads — and potentially people — to solar-powered climber robots positioned at the end of this 200,000+ mile long tether. The bots could then travel up the line to the moon’s surface.

This wouldn’t eliminate the need for rockets to get into Earth’s orbit, but it would be a cheaper way to get to the moon. The forces acting on a lunar space elevator wouldn’t be as strong as one extending from Earth’s surface, either, according to the researchers, opening up more options for tether materials.

“[T]he necessary strength of the material is much lower than an Earth-based elevator — and thus it could be built from fibers that are already mass-produced … and relatively affordable,” they wrote in a paper shared on the preprint server arXiv.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one.

Electrically powered climber capsules could go up down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

Adobe Stock

Some Chinese researchers, meanwhile, aren’t giving up on the idea of using carbon nanotubes for a space elevator — in 2018, a team from Tsinghua University revealed that they’d developed nanotubes that they say are strong enough for a tether.

The researchers are still working on the issue of scaling up production, but in 2021, state-owned news outlet Xinhua released a video depicting an in-development concept, called “Sky Ladder,” that would consist of space elevators above Earth and the moon.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one. If the project could be pulled off — a huge if — China predicts Sky Ladder could cut the cost of sending people and goods to the moon by 96 percent.

The bottom line

In the 120 years since Tsiolkovsky looked at the Eiffel Tower and thought way bigger, tremendous progress has been made developing materials with the properties needed for a space elevator. At this point, it seems likely we could one day have a material that can be manufactured at the scale needed for a tether — but by the time that happens, the need for a space elevator may have evaporated.

Several aerospace companies are making progress with their own reusable rockets, and as those join the market with SpaceX, competition could cause launch prices to fall further.

California startup SpinLaunch, meanwhile, is developing a massive centrifuge to fling payloads into space, where much smaller rockets can propel them into orbit. If the company succeeds (another one of those big ifs), it says the system would slash the amount of fuel needed to reach orbit by 70 percent.

Even if SpinLaunch doesn’t get off the ground, several groups are developing environmentally friendly rocket fuels that produce far fewer (or no) harmful emissions. More work is needed to efficiently scale up their production, but overcoming that hurdle will likely be far easier than building a 22,000-mile (35,400-km) elevator to space.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

New tech aims to make the ocean healthier for marine life

Overabundance of dissolved carbon dioxide poses a threat to marine life. A new system detects elevated levels of the greenhouse gases and mitigates them on the spot.

A defunct drydock basin arched by a rusting 19th century steel bridge seems an incongruous place to conduct state-of-the-art climate science. But this placid and protected sliver of water connecting Brooklyn’s Navy Yard to the East River was just right for Garrett Boudinot to float a small dock topped with water carbon-sensing gear. And while his system right now looks like a trio of plastic boxes wired up together, it aims to mediate the growing ocean acidification problem, caused by overabundance of dissolved carbon dioxide.

Boudinot, a biogeochemist and founder of a carbon-management startup called Vycarb, is honing his method for measuring CO2 levels in water, as well as (at least temporarily) correcting their negative effects. It’s a challenge that’s been occupying numerous climate scientists as the ocean heats up, and as states like New York recognize that reducing emissions won’t be enough to reach their climate goals; they’ll have to figure out how to remove carbon, too.

To date, though, methods for measuring CO2 in water at scale have been either intensely expensive, requiring fancy sensors that pump CO2 through membranes; or prohibitively complicated, involving a series of lab-based analyses. And that’s led to a bottleneck in efforts to remove carbon as well.

But recently, Boudinot cracked part of the code for measurement and mitigation, at least on a small scale. While the rest of the industry sorts out larger intricacies like getting ocean carbon markets up and running and driving carbon removal at billion-ton scale in centralized infrastructure, his decentralized method could have important, more immediate implications.

Specifically, for shellfish hatcheries, which grow seafood for human consumption and for coastal restoration projects. Some of these incubators for oysters and clams and scallops are already feeling the negative effects of excess carbon in water, and Vycarb’s tech could improve outcomes for the larval- and juvenile-stage mollusks they’re raising. “We’re learning from these folks about what their needs are, so that we’re developing our system as a solution that’s relevant,” Boudinot says.

Ocean acidification can wreak havoc on developing shellfish, inhibiting their shells from growing and leading to mass die-offs.

Ocean waters naturally absorb CO2 gas from the atmosphere. When CO2 accumulates faster than nature can dissipate it, it reacts with H2O molecules, forming carbonic acid, H2CO3, which makes the water column more acidic. On the West Coast, acidification occurs when deep, carbon dioxide-rich waters upwell onto the coast. This can wreak havoc on developing shellfish, inhibiting their shells from growing and leading to mass die-offs; this happened, disastrously, at Pacific Northwest oyster hatcheries in 2007.

This type of acidification will eventually come for the East Coast, too, says Ryan Wallace, assistant professor and graduate director of environmental studies and sciences at Long Island’s Adelphi University, who studies acidification. But at the moment, East Coast acidification has other sources: agricultural runoff, usually in the form of nitrogen, and human and animal waste entering coastal areas. These excess nutrient loads cause algae to grow, which isn’t a problem in and of itself, Wallace says; but when algae die, they’re consumed by bacteria, whose respiration in turn bumps up CO2 levels in water.

“Unfortunately, this is occurring at the bottom [of the water column], where shellfish organisms live and grow,” Wallace says. Acidification on the East Coast is minutely localized, occurring closest to where nutrients are being released, as well as seasonally; at least one local shellfish farm, on Fishers Island in the Long Island Sound, has contended with its effects.

The second Vycarb pilot, ready to be installed at the East Hampton shellfish hatchery.

Courtesy of Vycarb

Besides CO2, ocean water contains two other forms of dissolved carbon — carbonate (CO3-) and bicarbonate (HCO3) — at all times, at differing levels. At low pH (acidic), CO2 prevails; at medium pH, HCO3 is the dominant form; at higher pH, CO3 dominates. Boudinot’s invention is the first real-time measurement for all three, he says. From the dock at the Navy Yard, his pilot system uses carefully calibrated but low-cost sensors to gauge the water’s pH and its corresponding levels of CO2. When it detects elevated levels of the greenhouse gas, the system mitigates it on the spot. It does this by adding a bicarbonate powder that’s a byproduct of agricultural limestone mining in nearby Pennsylvania. Because the bicarbonate powder is alkaline, it increases the water pH and reduces the acidity. “We drive a chemical reaction to increase the pH to convert greenhouse gas- and acid-causing CO2 into bicarbonate, which is HCO3,” Boudinot says. “And HCO3 is what shellfish and fish and lots of marine life prefers over CO2.”

This de-acidifying “buffering” is something shellfish operations already do to water, usually by adding soda ash (NaHCO3), which is also alkaline. Some hatcheries add soda ash constantly, just in case; some wait till acidification causes significant problems. Generally, for an overly busy shellfish farmer to detect acidification takes time and effort. “We’re out there daily, taking a look at the pH and figuring out how much we need to dose it,” explains John “Barley” Dunne, director of the East Hampton Shellfish Hatchery on Long Island. “If this is an automatic system…that would be much less labor intensive — one less thing to monitor when we have so many other things we need to monitor.”

Across the Sound at the hatchery he runs, Dunne annually produces 30 million hard clams, 6 million oysters, and “if we’re lucky, some years we get a million bay scallops,” he says. These mollusks are destined for restoration projects around the town of East Hampton, where they’ll create habitat, filter water, and protect the coastline from sea level rise and storm surge. So far, Dunne’s hatchery has largely escaped the ill effects of acidification, although his bay scallops are having a finicky year and he’s checking to see if acidification might be part of the problem. But “I think it's important to have these solutions ready-at-hand for when the time comes,” he says. That’s why he’s hosting a second, 70-liter Vycarb pilot starting this summer on a dock adjacent to his East Hampton operation; it will amp up to a 50,000 liter-system in a few months.

If it can buffer water over a large area, absolutely this will benefit natural spawns. -- John “Barley” Dunne.

Boudinot hopes this new pilot will act as a proof of concept for hatcheries up and down the East Coast. The area from Maine to Nova Scotia is experiencing the worst of Atlantic acidification, due in part to increased Arctic meltwater combining with Gulf of St. Lawrence freshwater; that decreases saturation of calcium carbonate, making the water more acidic. Boudinot says his system should work to adjust low pH regardless of the cause or locale. The East Hampton system will eventually test and buffer-as-necessary the water that Dunne pumps from the Sound into 100-gallon land-based tanks where larvae grow for two weeks before being transferred to an in-Sound nursery to plump up.

Dunne says this could have positive effects — not only on his hatchery but on wild shellfish populations, too, reducing at least one stressor their larvae experience (others include increasing water temperatures and decreased oxygen levels). “If it can buffer water over a large area, absolutely this will [benefit] natural spawns,” he says.

No one believes the Vycarb model — even if it proves capable of functioning at much greater scale — is the sole solution to acidification in the ocean. Wallace says new water treatment plants in New York City, which reduce nitrogen released into coastal waters, are an important part of the equation. And “certainly, some green infrastructure would help,” says Boudinot, like restoring coastal and tidal wetlands to help filter nutrient runoff.

In the meantime, Boudinot continues to collect data in advance of amping up his own operations. Still unknown is the effect of releasing huge amounts of alkalinity into the ocean. Boudinot says a pH of 9 or higher can be too harsh for marine life, plus it can also trigger a release of CO2 from the water back into the atmosphere. For a third pilot, on Governor’s Island in New York Harbor, Vycarb will install yet another system from which Boudinot’s team will frequently sample to analyze some of those and other impacts. “Let's really make sure that we know what the results are,” he says. “Let's have data to show, because in this carbon world, things behave very differently out in the real world versus on paper.”