Tapping into the Power of the Placebo Effect

When Wayne Jonas was in medical school 40 years ago, doctors would write out a prescription for placebos, spelling it out backwards in capital letters, O-B-E-C-A-L-P. The pharmacist would fill the prescription with a sugar pill, recalls Jonas, now director of integrative health programs at the Samueli Foundation. It fulfilled the patient's desire for the doctor to do something when perhaps no drug could help, and the sugar pills did no harm.

Today, that deception is seen as unethical. But time and time again, studies have shown that placebos can have real benefits. Now, researchers are trying to untangle the mysteries of placebo effect in an effort to better treat patients.

The use of placebos took off in the post-WWII period, when randomized controlled clinical trials became the gold standard for medical research. One group in a study would be treated with a placebo, a supposedly inert pill or procedure that would not affect normal healing and recovery, while another group in the study would receive an "active" component, most commonly a pill under investigation. Presumably, the group receiving the active treatment would have a better response and the difference from the placebo group would represent the efficacy of the drug being tested. That was the basis for drug approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

"Placebo responses were marginalized," says Ted Kaptchuk, director of the Program in Placebo Studies & Therapeutic Encounters at Harvard Medical School. "Doctors were taught they have to overcome it when they were thinking about using an effective drug."

But that began to change around the turn of the 21st century. The National Institutes of Health held a series of meetings to set a research agenda and fund studies to answer some basic questions, led by Jonas who was in charge of the office of alternative medicine at the time. "People spontaneously get better all the time," says Kaptchuk. The crucial question was, is the placebo effect real? Is it more than just spontaneous healing?

Brain mechanisms

A turning point came in 2001 in a paper in Science that showed physical evidence of the placebo effect. It used positron emission tomography (PET) scans to measure release patterns of dopamine — a chemical messenger involved in how we feel pleasure — in the brains of patients with Parkinson's disease. Surprisingly, the placebo activated the same patterns that were activated by Parkinson's drugs, such as levodopa. It proved the placebo effect was real; now the search was on to better understand and control it.

A key part of the effect can be the beliefs, expectations, context, and "rituals" of the encounter between doctor and patient. Belief by the doctor and patient that the treatment would work, and the formalized practices of administering the treatment can all contribute to a positive outcome.

Conditioning can be another important component in generating a response, as Pavlov demonstrated more than a century ago in his experiments with dogs. They were trained with a bell prior to feeding such that they would begin to salivate in anticipation at the sound of a bell even with no food present.

Translating that to humans, studies with pain medications and sleeping aids showed that patients who had a positive response with a certain dose of those medications could have the same response if the doses was reduced and a dummy pill substituted, even to the point where there was no longer any active ingredient.

Researchers think placebo treatments can work particularly well in helping people deal with pain and psychological disorders.

Those types of studies troubled Kaptchuk because they often relied on deception; patients weren't told they were receiving a placebo, or at best there was a possibility that they might be randomized to receive a placebo. He believed the placebo effect could work even if patients were told upfront that they were going to receive a placebo. More than a dozen so call "open-label placebo" studies across numerous medical conditions, by Kaptchuk and others, have shown that you don't have to lie to patients for a placebo to work.

Jonas likes to tell the story of a patient who used methotrexate, a potent immunosuppressant, to control her rheumatoid arthritis. She was planning a long trip and didn't want to be bothered with the injections and monitoring required in using the drug, So she began to drink a powerful herbal extract of anise, a licorice flavor that she hated, prior to each injection. She reduced the amount of methotrexate over a period of months and finally stopped, but continued to drink the anise. That process had conditioned her body "to alter her immune function and her autoimmunity" as if she were taking the drug, much like Pavlov's dogs had been trained. She has not taken methotrexate for more than a year.

An intriguing paper published in May 2021 found that mild, non-invasive electric stimulation to the brain could not only boost the placebo effect on pain but also reduce the "nocebo" effect — when patients report a negative effect to a sham treatment. While the work is very preliminary, it may open the door to directly manipulating these responses.

Researchers think placebo treatments can work particularly well in helping people deal with pain and psychological disorders, areas where drugs often are of little help. Still, placebos aren't a cure and only a portion of patients experience a placebo effect.

Nocebo

If medicine were a soap opera, the nocebo would be the evil twin of the placebo. It's what happens when patients have adverse side effects because of the expectation that they will. It's commonly seem when patients claims to experience pain or gastric distress that can occur with a drug even when they've received a placebo. The side effects were either imagined or caused by something else.

"Up to 97% of reported pharmaceutical side effects are not caused by the drug itself but rather by nocebo effects and symptom misattribution," according to one 2019 paper.

One way to reduce a nocebo response is to simply not tell patients that specific side effects might occur. An example is a liver biopsy, in which a large-gauge needle is used to extract a tissue sample for examination. Those told ahead of time that they might experience some pain were more likely to report pain and greater pain than those who weren't offered this information.

Interestingly, a nocebo response plays out in the hippocampus, a part of the brain that is never activated in a placebo response. "I think what we are dealing with with nocebo is anxiety," says Kaptchuk, but he acknowledges that others disagree.

Distraction may be another way to minimize the nocebo effect. Pediatricians are using virtual reality (VR) to engage children and distract them during routine procedures such as blood draws and changing wound dressings, and burn patients of all ages have found relief with specially created VRs.

Treatment response

Jonas argues that what we commonly call the placebo effect is misnamed and leading us astray. "The fact is people heal and that inherent healing capacity is both powerful and influenced by mental, social, and contextual factors that are embedded in every medical encounter since the idea of treatment began," he wrote in a 2019 article in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry. "Our understanding of healing and ability to enhance it will be accelerated if we stop using the term 'placebo response' and call it what it is—the meaning response, and its special application in medicine called the healing response."

He cites evidence that "only 15% to 20% of the healing of an individual or a population comes from health care. The rest—nearly 80%—comes from other factors rarely addressed in the health care system: behavioral and lifestyle choices that people make in their daily life."

To better align treatments and maximize their effectiveness, Jonas has created HOPE (Healing Oriented Practices & Environments) Note, "a patient-guided process designed to identify the patient's values and goals in their life and for healing." Essentially, it seeks to make clear to both doctor and patient what the patient's goals are in seeking treatment. In an extreme example of terminal cancer, some patients may choose to extend life despite the often brutal treatments, while others might prefer to optimize quality of life in the remaining time that they have. It builds on practices already taught in medical schools. Jonas believes doctors and patients can use tools like these to maximize the treatment response and achieve better outcomes.

Much of the medical profession has been resistant to these approaches. Part of that is simply tradition and limited data on their effectiveness, but another very real factor is the billing process for how they are reimbursed. Jonas says a new medical billing code added this year gives doctors another way to be compensated for the extra time and effort that a more holistic approach to medicine may initially require. Other moves away from fee-for-service payments to bundling and payment for outcomes, and the integrated care provided by the Veterans Affairs, Kaiser Permanente and other groups offer longer term hope for the future of approaches that might enhance the healing response.

This article was first published by Leaps.org on July 7, 2021.

Probiotic bacteria can be engineered to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs by releasing chemicals that kill them.

In 1945, almost two decades after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, he warned that as antibiotics use grows, they may lose their efficiency. He was prescient—the first case of penicillin resistance was reported two years later. Back then, not many people paid attention to Fleming’s warning. After all, the “golden era” of the antibiotics age had just began. By the 1950s, three new antibiotics derived from soil bacteria — streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline — could cure infectious diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, meningitis and typhoid fever, among others.

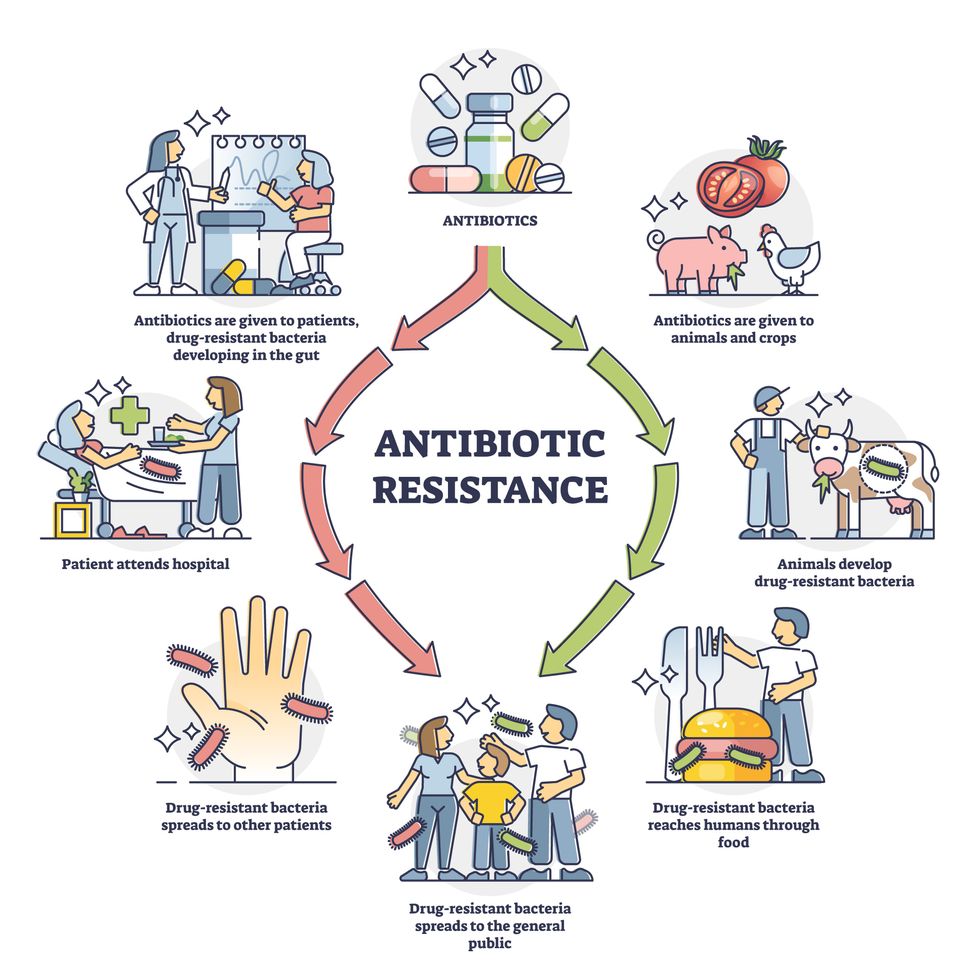

Today, these antibiotics and many of their successors developed through the 1980s are gradually losing their effectiveness. The extensive overuse and misuse of antibiotics led to the rise of drug resistance. The livestock sector buys around 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. every year. Farmers feed cows and chickens low doses of antibiotics to prevent infections and fatten up the animals, which eventually causes resistant bacterial strains to evolve. If manure from cattle is used on fields, the soil and vegetables can get contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Another major factor is doctors overprescribing antibiotics to humans, particularly in low-income countries. Between 2000 to 2018, the global rates of human antibiotic consumption shot up by 46 percent.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring a promising avenue: the use of synthetic biology to engineer new bacteria that may work better than antibiotics. The need continues to grow, as a Lancet study linked antibiotic resistance to over 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria. The western sub-Saharan Africa region had the highest death rate (27.3 people per 100,000).

Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

To make it worse, our remedy pipelines are drying up. Out of the 18 biggest pharmaceutical companies, 15 abandoned antibiotic development by 2013. According to the AMR Action Fund, venture capital has remained indifferent towards biotech start-ups developing new antibiotics. In 2019, at least two antibiotic start-ups filed for bankruptcy. As of December 2020, there were 43 new antibiotics in clinical development. But because they are based on previously known molecules, scientists say they are inadequate for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria. Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

The rise of synthetic biology

To circumvent this dire future, scientists have been working on alternative solutions using synthetic biology tools, meaning genetically modifying good bacteria to fight the bad ones.

From the time life evolved on earth around 3.8 billion years ago, bacteria have engaged in biological warfare. They constantly strategize new methods to combat each other by synthesizing toxic proteins that kill competition.

For example, Escherichia coli produces bacteriocins or toxins to kill other strains of E.coli that attempt to colonize the same habitat. Microbes like E.coli (which are not all pathogenic) are also naturally present in the human microbiome. The human microbiome harbors up to 100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells. The majority of them are beneficial organisms residing in the gut at different compositions.

The chemicals that these “good bacteria” produce do not pose any health risks to us, but can be toxic to other bacteria, particularly to human pathogens. For the last three decades, scientists have been manipulating bacteria’s biological warfare tactics to our collective advantage.

In the late 1990s, researchers drew inspiration from electrical and computing engineering principles that involve constructing digital circuits to control devices. In certain ways, every cell in living organisms works like a tiny computer. The cell receives messages in the form of biochemical molecules that cling on to its surface. Those messages get processed within the cells through a series of complex molecular interactions.

Synthetic biologists can harness these living cells’ information processing skills and use them to construct genetic circuits that perform specific instructions—for example, secrete a toxin that kills pathogenic bacteria. “Any synthetic genetic circuit is merely a piece of information that hangs around in the bacteria’s cytoplasm,” explains José Rubén Morones-Ramírez, a professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico. Then the ribosome, which synthesizes proteins in the cell, processes that new information, making the compounds scientists want bacteria to make. “The genetic circuit remains separated from the living cell’s DNA,” Morones-Ramírez explains. When the engineered bacteria replicates, the genetic circuit doesn’t become part of its genome.

Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut.

In 2000, Boston-based researchers constructed an E.coli with a genetic switch that toggled between turning genes on and off two. Later, they built some safety checks into their bacteria. “To prevent unintentional or deleterious consequences, in 2009, we built a safety switch in the engineered bacteria’s genetic circuit that gets triggered after it gets exposed to a pathogen," says James Collins, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and faculty member at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “After getting rid of the pathogen, the engineered bacteria is designed to switch off and leave the patient's body.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics causes resistant strains to evolve

Adobe Stock

Seek and destroy

As the field of synthetic biology developed, scientists began using engineered bacteria to tackle superbugs. They first focused on Vibrio cholerae, which in the 19th and 20th century caused cholera pandemics in India, China, the Middle East, Europe, and Americas. Like many other bacteria, V. cholerae communicate with each other via quorum sensing, a process in which the microorganisms release different signaling molecules, to convey messages to its brethren. Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut. When untreated, cholera has a mortality rate of 25 to 50 percent and outbreaks frequently occur in developing countries, especially during floods and droughts.

Sometimes, however, V. cholerae makes mistakes. In 2008, researchers at Cornell University observed that when quorum sensing V. cholerae accidentally released high concentrations of a signaling molecule called CAI-1, it had a counterproductive effect—the pathogen couldn’t colonize the gut.

So the group, led by John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering, developed a novel strategy to combat V. cholerae. They genetically engineered E.coli to eavesdrop on V. cholerae communication networks and equipped it with the ability to release the CAI-1 molecules. That interfered with V. cholerae progress. Two years later, the Cornell team showed that V. cholerae-infected mice treated with engineered E.coli had a 92 percent survival rate.

These findings inspired researchers to sic the good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi onto the drug-resistant ones.

Three years later in 2011, Singapore-based scientists engineered E.coli to detect and destroy Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an often drug-resistant pathogen that causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. Once the genetically engineered E.coli found its target through its quorum sensing molecules, it then released a peptide, that could eradicate 99 percent of P. aeruginosa cells in a test-tube experiment. The team outlined their work in a Molecular Systems Biology study.

“At the time, we knew that we were entering new, uncharted territory,” says lead author Matthew Chang, an associate professor and synthetic biologist at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the study. “To date, we are still in the process of trying to understand how long these microbes stay in our bodies and how they might continue to evolve.”

More teams followed the same path. In a 2013 study, MIT researchers also genetically engineered E.coli to detect P. aeruginosa via the pathogen’s quorum-sensing molecules. It then destroyed the pathogen by secreting a lab-made toxin.

Probiotics that fight

A year later in 2014, a Nature study found that the abundance of Ruminococcus obeum, a probiotic bacteria naturally occurring in the human microbiome, interrupts and reduces V.cholerae’s colonization— by detecting the pathogen’s quorum sensing molecules. The natural accumulation of R. obeum in Bangladeshi adults helped them recover from cholera despite living in an area with frequent outbreaks.

The findings from 2008 to 2014 inspired Collins and his team to delve into how good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi can attack drug-resistant bacteria. In 2018, Collins and his team developed the engineered probiotic strategy. They tweaked a bacteria commonly found in yogurt called Lactococcus lactis to treat cholera.

Engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut. --José Rubén Morones-Ramírez.

More scientists followed with more experiments. So far, researchers have engineered various probiotic organisms to fight pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (leading cause of skin, tissue, bone, joint and blood infections) and Clostridium perfringens (which causes watery diarrhea) in test-tube and animal experiments. In 2020, Russian scientists engineered a probiotic called Pichia pastoris to produce an enzyme called lysostaphin that eradicated S. aureus in vitro. Another 2020 study from China used an engineered probiotic bacteria Lactobacilli casei as a vaccine to prevent C. perfringens infection in rabbits.

In a study last year, Ramírez’s group at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, engineered E. coli to detect quorum-sensing molecules from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA, a notorious superbug. The E. coli then releases a bacteriocin that kills MRSA. “An antibiotic is just a molecule that is not intelligent,” says Ramírez. “On the other hand, engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut.”

Collins and Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, found that engineered E. coli can help treat other conditions—such as phenylketonuria, a rare metabolic disorder, that causes the build-up of an amino acid phenylalanine. Their start-up Synlogic aims to commercialize the technology, and has completed a phase 2 clinical trial.

Circumventing the challenges

The bacteria-engineering technique is not without pitfalls. One major challenge is that beneficial gut bacteria produce their own quorum-sensing molecules that can be similar to those that pathogens secrete. If an engineered bacteria’s biosensor is not specific enough, it will be ineffective.

Another concern is whether engineered bacteria might mutate after entering the gut. “As with any technology, there are risks where bad actors could have the capability to engineer a microbe to act quite nastily,” says Collins of MIT. But Collins and Ramírez both insist that the chances of the engineered bacteria mutating on its own are virtually non-existent. “It is extremely unlikely for the engineered bacteria to mutate,” Ramírez says. “Coaxing a living cell to do anything on command is immensely challenging. Usually, the greater risk is that the engineered bacteria entirely lose its functionality.”

However, the biggest challenge is bringing the curative bacteria to consumers. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in antibiotics or their alternatives because it’s less profitable than developing new medicines for non-infectious diseases. Unlike the more chronic conditions like diabetes or cancer that require long-term medications, infectious diseases are usually treated much quicker. Running clinical trials are expensive and antibiotic-alternatives aren’t lucrative enough.

“Unfortunately, new medications for antibiotic resistant infections have been pushed to the bottom of the field,” says Lu of MIT. “It's not because the technology does not work. This is more of a market issue. Because clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the only solution is that governments will need to fund them.” Lu stresses that societies must lobby to change how the modern healthcare industry works. “The whole world needs better treatments for antibiotic resistance.”

Meet Dr. Renee Wegrzyn, the first Director of President Biden's new health agency, ARPA-H

Today's podcast guest, Dr. Renee Wegrzyn, directs ARPA-H, a new agency formed last year to spearhead health innovations. Time will tell if ARPA-H will produce advances on the level of its fellow agency, DARPA.

In today’s podcast episode, I talk with Renee Wegrzyn, appointed by President Biden as the first director of a health agency created last year, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H. It’s inspired by DARPA, the agency that develops innovations for the Defense department and has been credited with hatching world-changing technologies such as ARPANET, which became the internet.

Time will tell if ARPA-H will lead to similar achievements in the realm of health. That’s what President Biden and Congress expect in return for funding ARPA-H at 2.5 billion dollars over three years.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

How will the agency figure out which projects to take on, especially with so many patient advocates for different diseases demanding moonshot funding for rapid progress?

I talked with Dr. Wegrzyn about the opportunities and challenges, what lessons ARPA-H is borrowing from Operation Warp Speed, how she decided on the first ARPA-H project that was announced recently, why a separate agency was needed instead of reforming HHS and the National Institutes of Health to be better at innovation, and how ARPA-H will make progress on disease prevention in addition to treatments for cancer, Alzheimer’s and diabetes, among many other health priorities.

Dr. Wegrzyn’s resume leaves no doubt of her suitability for this role. She was a program manager at DARPA where she focused on applying gene editing and synthetic biology to the goal of improving biosecurity. For her work there, she received the Superior Public Service Medal and, in case that wasn’t enough ARPA experience, she also worked at another ARPA that leads advanced projects in intelligence, called I-ARPA. Before that, she ran technical teams in the private sector working on gene therapies and disease diagnostics, among other areas. She has been a vice president of business development at Gingko Bioworks and headed innovation at Concentric by Gingko. Her training and education includes a PhD and undergraduate degree in applied biology from the Georgia Institute of Technology and she did her postdoc as an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow in Heidelberg, Germany.

Dr. Wegrzyn told me that she’s “in the hot seat.” The pressure is on for ARPA-H especially after the need and potential for health innovation was spot lit by the pandemic and the unprecedented speed of vaccine development. We'll soon find out if ARPA-H can produce gamechangers in health that are equivalent to DARPA’s creation of the internet.

Show links:

ARPA-H - https://arpa-h.gov/

Dr. Wegrzyn profile - https://arpa-h.gov/people/renee-wegrzyn/

Dr. Wegrzyn Twitter - https://twitter.com/rwegrzyn?lang=en

President Biden Announces Dr. Wegrzyn's appointment - https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statement...

Leaps.org coverage of ARPA-H - https://leaps.org/arpa/

ARPA-H program for joints to heal themselves - https://arpa-h.gov/news/nitro/ -

ARPA-H virtual talent search - https://arpa-h.gov/news/aco-talent-search/

Dr. Renee Wegrzyn was appointed director of ARPA-H last October.