Pseudoscience Is Rampant: How Not to Fall for It

A metaphorical rendering of scientific truth gone awry.

Whom to believe?

The relentless and often unpredictable coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has, among its many quirky terrors, dredged up once again the issue that will not die: science versus pseudoscience.

How does one learn to spot the con without getting a Ph.D. and spending years in a laboratory?

The scientists, experts who would be the first to admit they are not infallible, are now in danger of being drowned out by the growing chorus of pseudoscientists, conspiracy theorists, and just plain troublemakers that seem to be as symptomatic of the virus as fever and weakness.

How is the average citizen to filter this cacophony of information and misinformation posing as science alongside real science? While all that noise makes it difficult to separate the real stuff from the fakes, there is at least one positive aspect to it all.

A famous aphorism by one Charles Caleb Colton, a popular 19th-century English cleric and writer, says that "imitation is the sincerest form of flattery."

The frauds and the paranoid conspiracy mongers who would perpetrate false science on a susceptible public are at least recognizing the value of science—they imitate it. They imitate the ways in which science works and make claims as if they were scientists, because even they recognize the power of a scientific approach. They are inadvertently showing us how much we value science. Unfortunately they are just shabby counterfeits.

Separating real science from pseudoscience is not a new problem. Philosophers, politicians, scientists, and others have been worrying about this perhaps since science as we know it, a science based entirely on experiment and not opinion, arrived in the 1600s. The original charter of the British Royal Society, the first organized scientific society, stated that at their formal meetings there would be no discussion of politics, religion, or perpetual motion machines.

The first two of those for the obvious purpose of keeping the peace. But the third is interesting because at that time perpetual motion machines were one of the main offerings of the imitators, the bogus scientists who were sure that you could find ways around the universal laws of energy and make a buck on it. The motto adopted by the society was, and remains, Nullius in verba, Latin for "take nobody's word for it." Kind of an early version of Missouri's venerable state motto: "Show me."

You might think that telling phony science from the real thing wouldn't be so difficult, but events, historical and current, tell a very different story—often with tragic outcomes. Just one terrible example is the estimated 350,000 additional HIV deaths in South Africa directly caused by the now-infamous conspiracy theories of their own elected President no less (sound familiar?). It's surprisingly easy to dress up phony science as the real thing by simply adopting, or appearing to adopt, the trappings of science.

Thus, the anti-vaccine movement claims to be based on suspicion of authority, beginning with medical authority in this case, stemming from the fraudulent data published by the now-disgraced Andrew Wakefield, an English gastroenterologist. And it's true that much of science is based on suspicion of authority. Science got its start when the likes of Galileo and Copernicus claimed that the Church, the State, even Aristotle, could no longer be trusted as authoritative sources of knowledge.

But Galileo and those who followed him produced alternative explanations, and those alternatives were based on data that arose independently from many sources and generated a great deal of debate and, most importantly, could be tested by experiments that could prove them wrong. The anti-vaccine movement imitates science, still citing the discredited Wakefield report, but really offers nothing but suspicion—and that is paranoia, not science.

Similarly, there are those who try to cloak their nefarious motives in the trappings of science by claiming that they are taking the scientific posture of doubt. Science after all depends on doubt—every scientist doubts every finding they make. Every scientist knows that they can't possibly foresee all possible instances or situations in which they could be proven wrong, no matter how strong their data. Einstein was doubted for two decades, and cosmologists are still searching for experimental proofs of relativity. Science indeed progresses by doubt. In science revision is a victory.

But the imitators merely use doubt to suggest that science is not dependable and should not be used for informing policy or altering our behavior. They claim to be taking the legitimate scientific stance of doubt. Of course, they don't doubt everything, only what is problematic for their individual enterprises. They don't doubt the value of blood pressure medicine to control their hypertension. But they should, because every medicine has side effects and we don't completely understand how blood pressure is regulated and whether there may not be still better ways of controlling it.

But we use the pills we have because the science is sound even when it is not completely settled. Ask a hypertensive oil executive who would like you to believe that climate science should be ignored because there are too many uncertainties in the data, if he is willing to forgo his blood pressure medicine—because it, too, has its share of uncertainties and unwanted side effects.

The apparent success of pseudoscience is not due to gullibility on the part of the public. The problem is that science is recognized as valuable and that the imitators are unfortunately good at what they do. They take a scientific pose to gain your confidence and then distort the facts to their own purposes. How does one learn to spot the con without getting a Ph.D. and spending years in a laboratory?

"If someone claims to have the ultimate answer or that they know something for certain, the only thing for sure is that they are trying to fool you."

What can be done to make the distinction clearer? Several solutions have been tried—and seem to have failed. Radio and television shows about the latest scientific breakthroughs are a noble attempt to give the public a taste of good science, but they do nothing to help you distinguish between them and the pseudoscience being purveyed on the neighboring channel and its "scientific investigations" of haunted houses.

Similarly, attempts to inculcate what are called "scientific habits of mind" are of little practical help. These habits of mind are not so easy to adopt. They invariably require some amount of statistics and probability and much of that is counterintuitive—one of the great values of science is to help us to counter our normal biases and expectations by showing that the actual measurements may not bear them out.

Additionally, there is math—no matter how much you try to hide it, much of the language of science is math (Galileo said that). And half the audience is gone with each equation (Stephen Hawking said that). It's hard to imagine a successful program of making a non-scientifically trained public interested in adopting the rigors of scientific habits of mind. Indeed, I suspect there are some people, artists for example, who would be rightfully suspicious of changing their thinking to being habitually scientific. Many scientists are frustrated by the public's inability to think like a scientist, but in fact it is neither easy nor always desirable to do so. And it is certainly not practical.

There is a more intuitive and simpler way to tell the difference between the real thing and the cheap knock-off. In fact, it is not so much intuitive as it is counterintuitive, so it takes a little bit of mental work. But the good thing is it works almost all the time by following a simple, if as I say, counterintuitive, rule.

True science, you see, is mostly concerned with the unknown and the uncertain. If someone claims to have the ultimate answer or that they know something for certain, the only thing for sure is that they are trying to fool you. Mystery and uncertainty may not strike you right off as desirable or strong traits, but that is precisely where one finds the creative solutions that science has historically arrived at. Yes, science accumulates factual knowledge, but it is at its best when it generates new and better questions. Uncertainty is not a place of worry, but of opportunity. Progress lives at the border of the unknown.

How much would it take to alter the public perception of science to appreciate unknowns and uncertainties along with facts and conclusions? Less than you might think. In fact, we make decisions based on uncertainty every day—what to wear in case of 60 percent chance of rain—so it should not be so difficult to extend that to science, in spite of what you were taught in school about all the hard facts in those giant textbooks.

You can believe science that says there is clear evidence that takes us this far… and then we have to speculate a bit and it could go one of two or three ways—or maybe even some way we don't see yet. But like your blood pressure medicine, the stuff we know is reliable even if incomplete. It will lower your blood pressure, no matter that better treatments with fewer side effects may await us in the future.

Unsettled science is not unsound science. The honesty and humility of someone who is willing to tell you that they don't have all the answers, but they do have some thoughtful questions to pursue, are easy to distinguish from the charlatans who have ready answers or claim that nothing should be done until we are an impossible 100-percent sure.

Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery.

The problem, as we all know, is that flattery will get you nowhere.

[Editor's Note: This article was originally published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]

Nobel Prize goes to technology for mRNA vaccines

Katalin Karikó, pictured, and Drew Weissman won the Nobel Prize for advances in mRNA research that led to the first Covid vaccines.

When Drew Weissman received a call from Katalin Karikó in the early morning hours this past Monday, he assumed his longtime research partner was calling to share a nascent, nagging idea. Weissman, a professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and Karikó, a professor at Szeged University and an adjunct professor at UPenn, both struggle with sleep disturbances. Thus, middle-of-the-night discourses between the two, often over email, has been a staple of their friendship. But this time, Karikó had something more pressing and exciting to share: They had won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

The work for which they garnered the illustrious award and its accompanying $1,000,000 cash windfall was completed about two decades ago, wrought through long hours in the lab over many arduous years. But humanity collectively benefited from its life-saving outcome three years ago, when both Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccines against COVID were found to be safe and highly effective at preventing severe disease. Billions of doses have since been given out to protect humans from the upstart viral scourge.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” said Katalin Karikó. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

Unlocking the power of mRNA

Weissman and Karikó unlocked mRNA vaccines for the world back in the early 2000s when they made a key breakthrough. Messenger RNA molecules are essentially instructions for cells’ ribosomes to make specific proteins, so in the 1980s and 1990s, researchers started wondering if sneaking mRNA into the body could trigger cells to manufacture antibodies, enzymes, or growth agents for protecting against infection, treating disease, or repairing tissues. But there was a big problem: injecting this synthetic mRNA triggered a dangerous, inflammatory immune response resulting in the mRNA’s destruction.

While most other researchers chose not to tackle this perplexing problem to instead pursue more lucrative and publishable exploits, Karikó stuck with it. The choice sent her academic career into depressing doldrums. Nobody would fund her work, publications dried up, and after six years as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó got demoted. She was going backward.

“I thought of going somewhere else, or doing something else,” Karikó told Stat in 2020. “I also thought maybe I’m not good enough, not smart enough. I tried to imagine: Everything is here, and I just have to do better experiments.”

A tale of tenacity

Collaborating with Drew Weissman, a new professor at the University of Pennsylvania, in the late 1990s helped provide Karikó with the tenacity to continue. Weissman nurtured a goal of developing a vaccine against HIV-1, and saw mRNA as a potential way to do it.

“For the 20 years that we’ve worked together before anybody knew what RNA is, or cared, it was the two of us literally side by side at a bench working together,” Weissman said in an interview with Adam Smith of the Nobel Foundation.

In 2005, the duo made their 2023 Nobel Prize-winning breakthrough, detailing it in a relatively small journal, Immunity. (Their paper was rejected by larger journals, including Science and Nature.) They figured out that chemically modifying the nucleoside bases that make up mRNA allowed the molecule to slip past the body’s immune defenses. Karikó and Weissman followed up that finding by creating mRNA that’s more efficiently translated within cells, greatly boosting protein production. In 2020, scientists at Moderna and BioNTech (where Karikó worked from 2013 to 2022) rushed to craft vaccines against COVID, putting their methods to life-saving use.

The future of vaccines

Buoyed by the resounding success of mRNA vaccines, scientists are now hurriedly researching ways to use mRNA medicine against other infectious diseases, cancer, and genetic disorders. The now ubiquitous efforts stand in stark contrast to Karikó and Weissman’s previously unheralded struggles years ago as they doggedly worked to realize a shared dream that so many others shied away from. Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman were brave enough to walk a scientific path that very well could have ended in a dead end, and for that, they absolutely deserve their 2023 Nobel Prize.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

Scientists turn pee into power in Uganda

With conventional fuel cells as their model, researchers learned to use similar chemical reactions to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

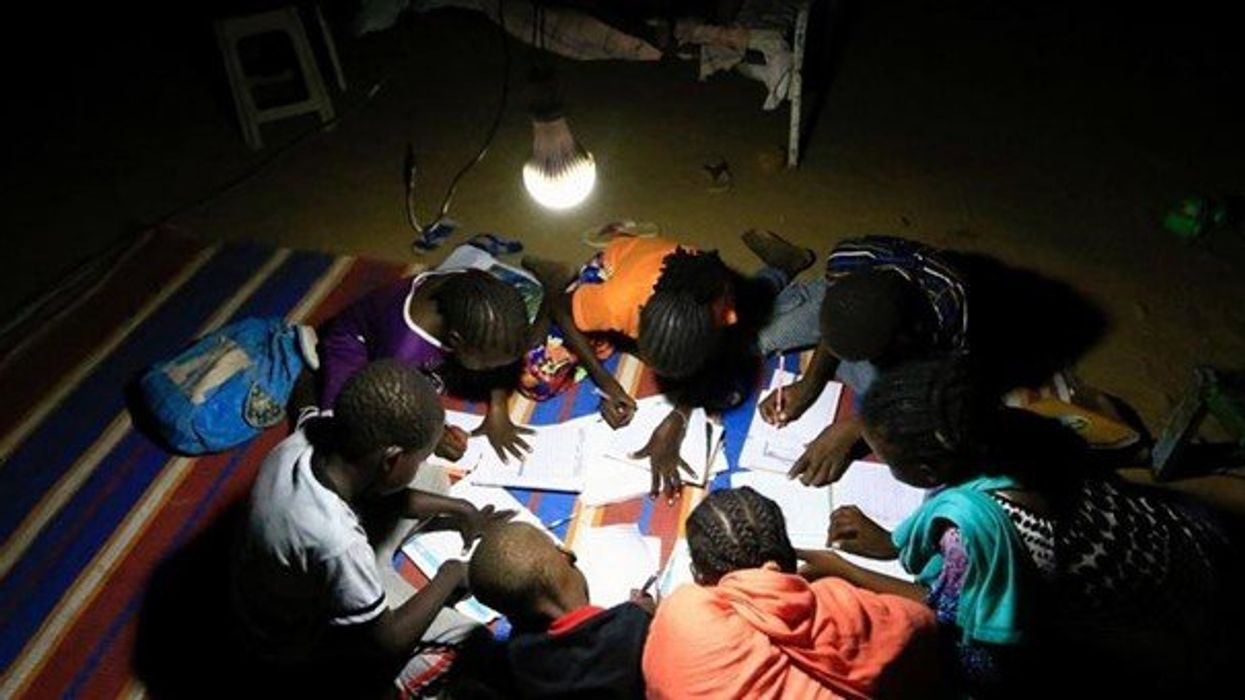

At the edge of a dirt road flanked by trees and green mountains outside the town of Kisoro, Uganda, sits the concrete building that houses Sesame Girls School, where girls aged 11 to 19 can live, learn and, at least for a while, safely use a toilet. In many developing regions, toileting at night is especially dangerous for children. Without electrical power for lighting, kids may fall into the deep pits of the latrines through broken or unsteady floorboards. Girls are sometimes assaulted by men who hide in the dark.

For the Sesame School girls, though, bright LED lights, connected to tiny gadgets, chased the fears away. They got to use new, clean toilets lit by the power of their own pee. Some girls even used the light provided by the latrines to study.

Urine, whether animal or human, is more than waste. It’s a cheap and abundant resource. Each day across the globe, 8.1 billion humans make 4 billion gallons of pee. Cows, pigs, deer, elephants and other animals add more. By spending money to get rid of it, we waste a renewable resource that can serve more than one purpose. Microorganisms that feed on nutrients in urine can be used in a microbial fuel cell that generates electricity – or "pee power," as the Sesame girls called it.

Plus, urine contains water, phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen, the key ingredients plants need to grow and survive. Human urine could replace about 25 percent of current nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers worldwide and could save water for gardens and crops. The average U.S. resident flushes a toilet bowl containing only pee and paper about six to seven times a day, which adds up to about 3,500 gallons of water down per year. Plus cows in the U.S. produce 231 gallons of the stuff each year.

Pee power

A conventional fuel cell uses chemical reactions to produce energy, as electrons move from one electrode to another to power a lightbulb or phone. Ioannis Ieropoulos, a professor and chair of Environmental Engineering at the University of Southampton in England, realized the same type of reaction could be used to make a fuel from microbes in pee.

Bacterial species like Shewanella oneidensis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa can consume carbon and other nutrients in urine and pop out electrons as a result of their digestion. In a microbial fuel cell, one electrode is covered in microbes, immersed in urine and kept away from oxygen. Another electrode is in contact with oxygen. When the microbes feed on nutrients, they produce the electrons that flow through the circuit from one electrod to another to combine with oxygen on the other side. As long as the microbes have fresh pee to chomp on, electrons keep flowing. And after the microbes are done with the pee, it can be used as fertilizer.

These microbes are easily found in wastewater treatment plants, ponds, lakes, rivers or soil. Keeping them alive is the easy part, says Ieropoulos. Once the cells start producing stable power, his group sequences the microbes and keeps using them.

Like many promising technologies, scaling these devices for mass consumption won’t be easy, says Kevin Orner, a civil engineering professor at West Virginia University. But it’s moving in the right direction. Ieropoulos’s device has shrunk from the size of about three packs of cards to a large glue stick. It looks and works much like a AAA battery and produce about the same power. By itself, the device can barely power a light bulb, but when stacked together, they can do much more—just like photovoltaic cells in solar panels. His lab has produced 1760 fuel cells stacked together, and with manufacturing support, there’s no theoretical ceiling, he says.

Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofit into urban wastewater utilities.

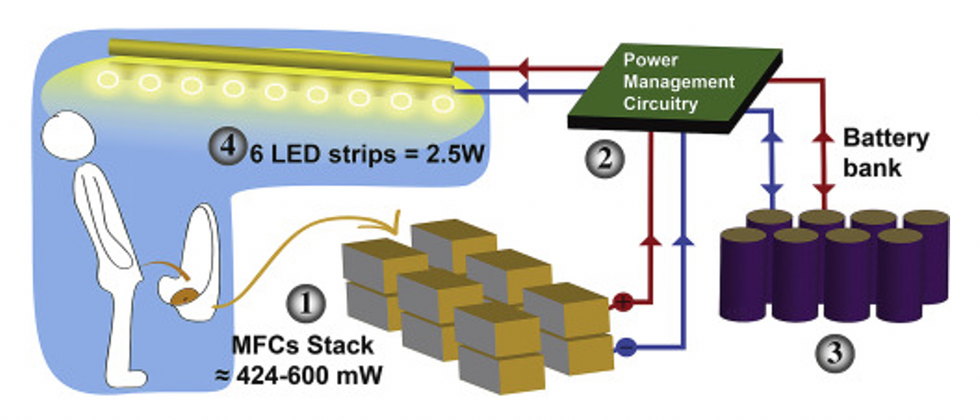

This image shows how the pee-powered system works. Pee feeds bacteria in the stack of fuel cells (1), which give off electrons (2) stored in parallel cylindrical cells (3). These cells are connected to a voltage regulator (4), which smooths out the electrical signal to ensure consistent power to the LED strips lighting the toilet.

Courtesy Ioannis Ieropoulos

Key to the long-term success of any urine reclamation effort, says Orner, is avoiding what he calls “parachute engineering”—when well-meaning scientists solve a problem with novel tech and then abandon it. “The way around that is to have either the need come from the community or to have an organization in a community that is committed to seeing a project operate and maintained,” he says.

Success with urine reclamation also depends on the economy. “If energy prices are low, it may not make sense to recover energy,” says Orner. “But right now, fertilizer prices worldwide are generally pretty high, so it may make sense to recover fertilizer and nutrients.” There are obstacles, too, such as few incentives for builders to incorporate urine recycling into new construction. And any hiccups like leaks or waste seepage will cost builders money and reputation. Right now, Orner says, the risks are just too high.

Despite the challenges, Ieropoulos envisions a future in which urine is passed through microbial fuel cells at wastewater treatment plants, retrofitted septic tanks, and building basements, and is then delivered to businesses to use as agricultural fertilizers. Although pure urine produces the most power, Ieropoulos’s devices also work with the mixed liquids of the wastewater treatment plants, so they can be retrofitted into urban wastewater utilities where they can make electricity from the effluent. And unlike solar cells, which are a common target of theft in some areas, nobody wants to steal a bunch of pee.

When Ieropoulos’s team returned to wrap up their pilot project 18 months later, the school’s director begged them to leave the fuel cells in place—because they made a major difference in students’ lives. “We replaced it with a substantial photovoltaic panel,” says Ieropoulos, They couldn’t leave the units forever, he explained, because of intellectual property reasons—their funders worried about theft of both the technology and the idea. But the photovoltaic replacement could be stolen, too, leaving the girls in the dark.

The story repeated itself at another school, in Nairobi, Kenya, as well as in an informal settlement in Durban, South Africa. Each time, Ieropoulos vowed to return. Though the pandemic has delayed his promise, he is resolute about continuing his work—it is a moral and legal obligation. “We've made a commitment to ourselves and to the pupils,” he says. “That's why we need to go back.”

Urine as fertilizer

Modern day industrial systems perpetuate the broken cycle of nutrients. When plants grow, they use up nutrients the soil. We eat the plans and excrete some of the nutrients we pass them into rivers and oceans. As a result, farmers must keep fertilizing the fields while our waste keeps fertilizing the waterways, where the algae, overfertilized with nitrogen, phosphorous and other nutrients grows out of control, sucking up oxygen that other marine species need to live. Few global communities remain untouched by the related challenges this broken chain create: insufficient clean water, food, and energy, and too much human and animal waste.

The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont runs a community-wide urine nutrient recovery program, which collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms.

One solution to this broken cycle is reclaiming urine and returning it back to the land. The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont is one of several organizations around the world working to divert and save urine for agricultural use. “The urine produced by an adult in one day contains enough fertilizer to grow all the wheat in one loaf of bread,” states their website.

Notably, while urine is not entirely sterile, it tends to harbor fewer pathogens than feces. That’s largely because urine has less organic matter and therefore less food for pathogens to feed on, but also because the urinary tract and the bladder have built-in antimicrobial defenses that kill many germs. In fact, the Rich Earth Institute says it’s safe to put your own urine onto crops grown for home consumption. Nonetheless, you’ll want to dilute it first because pee usually has too much nitrogen and can cause “fertilizer burn” if applied straight without dilution. Other projects to turn urine into fertilizer are in progress in Niger, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sweden, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Australia, and France.

Eleven years ago, the Institute started a program that collects urine from homes and businesses, transports it for processing, and then supplies it as fertilizer to local farms. By 2021, the program included 180 donors producing over 12,000 gallons of urine each year. This urine is helping to fertilize hay fields at four partnering farms. Orner, the West Virginia professor, sees it as a success story. “They've shown how you can do this right--implementing it at a community level scale."