Rehabilitating psychedelic drugs: Another key to treating severe mental health disorders

A recent review paper found evidence that using psychedelics such as MDMA can help with treating a variety of common mental illnesses, but experts fear that research might easily be shut down in the future.

Lori Tipton's life was a cascade of trauma that even a soap opera would not dare inflict upon a character: a mentally unstable family; a brother who died of a drug overdose; the shocking discovery of the bodies of two persons her mother had killed before turning the gun on herself; the devastation of Hurricane Katrina that savaged her hometown of New Orleans; being raped by someone she trusted; and having an abortion. She suffered from severe PTSD.

“My life was filled with anxiety and hypervigilance,” she says. “I was constantly afraid and had mood swings, panic attacks, insomnia, intrusive thoughts and suicidal ideation. I tried to take my life more than once.” She was fortunate to be able to access multiple mental health services, “And while at times some of these modalities would relieve the symptoms, nothing really lasted and nothing really address the core trauma.”

Then in 2018 Tipton enrolled in a clinical trial that combined intense sessions of psychotherapy with limited use of Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or MDMA, a drug classified as a psychedelic and commonly known as ecstasy or Molly. The regimen was arduous; 1-2 hour preparation sessions, three sessions where MDMA was used, which lasted 6-8 hours, and lengthy sessions afterward to process and integrate the experiences. Two therapists were with her every moment of the three-month program that totaled more than 40 hours.

“It was clear to me that [the therapists] weren't going to heal me, that I was going to have to do the work for myself, but that they were there to completely support my process,” she says. “But the effects of MDMA were really undeniable for me. I felt embodied in a way that I hadn't in years. PTSD had robbed me of the ability to feel safe in my own body.”

Tipton doesn’t think the therapy completely cured her PTSD. “But when I completed the trial in 2018, I no longer qualified for the diagnosis, and I still don't qualify for the diagnosis today,” she told an April workshop on psychedelics as mental health treatment by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, or NASEM.

A Champion

Rick Doblin has been a catalyst behind much of the contemporary research into psychedelics. Prior to the DEA clamp down, the Boston psychotherapist had seen that MDMA and other psychedelics could benefit some of his patients where other measures had failed. He immediately organized efforts to question the drug rescheduling but to little avail. In 1986, he created the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which slowly laid the scientific foundation for clinical trials, including the one that Tipton joined, using psychedelics to treat mental health conditions.

Now, only slowly, have researchers been able to explore the power of these drugs to treat a broad spectrum of severely debilitating mental health conditions, including trauma, depression, and PTSD, where other available treatments proved inadequate.

“Psychedelic psychotherapy is an attempt to go after the root causes of the problems with just a relatively few administrations, as contrasted to most of the psychiatric drugs used today that are mostly just reducing symptoms and are meant to be taken on a daily basis,” Doblin said in a 2019 TED Talk. Most of these drugs can have broad effect but “some are probably more effective than others for certain conditions,” he added in a recent interview with Leaps.org. Comparative head-to-head studies of psychedelic therapies simply have not been conducted.

Their mechanisms of action are poorly understood and can vary between drugs, but it is generally believed that psychedelics change the activity of neurons so that the brain processes information differently, says Katrin Preller, a neuropsychologist at the University of Zurich. A recent important study in Nature Medicine by Richard Daws and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of the brain and found that “functional networks became more functionally interconnected and flexible after psilocybin treatment…implying that psilocybin's antidepressant action may depend on a global increase in brain network integration.”

Rosalind Watts, a clinical investigator at the Imperial College in London, believes there is “an overestimation of the importance of the drug and an underestimation of the importance of the [therapeutic] context” in psychedelic research. “It is unethical to provide the drug without the other,” she says. Doblin notes that “psychotherapy outcomes research demonstrates that the therapeutic alliance between the therapist and the patients is the single most predictive factor of outcomes. [It is] trust and the sense of safety, the willingness to go into difficult spaces” that makes clinical breakthroughs possible with the drug.

Excitement and Challenges

Recurrent themes expressed at the NASEM workshop were exciting glimpses of the potential for psychedelics to treat mental health conditions combined with the challenges of realizing those potentials. A recent review paper found evidence that using psychedelics can help with treating a variety of common mental illnesses, but the paper could identify only 14 clinical trials of classic psychedelics published since 1991. Much of the reason is that the drugs are not patentable and so the pharmaceutical industry has no interest in investing in expensive clinical trials to bring them to market. MAPS has raised about $135 million over its 36-year history to conduct such research, says Doblin, the vast majority of it from individual donors and none from foundations.

The workshop participants’ views also were colored by the history of drug crackdowns and a fear that research might easily be shut down in the future. There was great concern that use of psychedelics should be confined to clinical trials with high safety and ethical standards, instead of doctors and patients experimenting on their own. “We need to get it right this time,” says Charles Grob, a psychiatrist at the UCLA School of Medicine. But restricting access to psychedelics will become even more difficult now that Oregon and several cities have acted to decriminalize possession and use of many of these drugs.

The experience with ketamine also troubled Grob. He is hoping to “mitigate the rush of rapid commercialization” that occurred with that drug. Ketamine technically is not a psychedelic though it does share some of their potentially euphoric properties. In 2019, soon after the FDA approved a form of ketamine with a limited label indication to treat depression, for profit clinics sprang up promoting off label use of the drug for psychiatric conditions where there was little clinical evidence of efficacy. He fears the same thing will happen when true psychedelics are made available.

If these therapies are approved, access to them is likely to be a problem. The drugs themselves are cheap but the accompanying therapy is not, and there is a shortage of trained psychotherapists. Mental health services often are not adequately covered by health insurance, while the poor and people of color suffer additional burdens of inadequate access. Doblin is committed to health care equity by training additional providers and by investigating whether some of the preparatory and integration sessions might be handled in a group setting. He says it is important that the legal aspects of psychedelics also be addressed so that patients “don't have to go underground” in order to receive this care.

In this week's Friday Five, an old diabetes drug finds an exciting new purpose. Plus, how to make the cities of the future less toxic, making old mice younger with EVs, a new reason for mysterious stillbirths - and much more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here is the promising research covered in this week's Friday Five:

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

- How to make cities of the future less noisy

- An old diabetes drug could have a new purpose: treating an irregular heartbeat

- A new reason for mysterious stillbirths

- Making old mice younger with EVs

- No pain - or mucus - no gain

And an honorable mention this week: How treatments for depression can change the structure of the brain

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

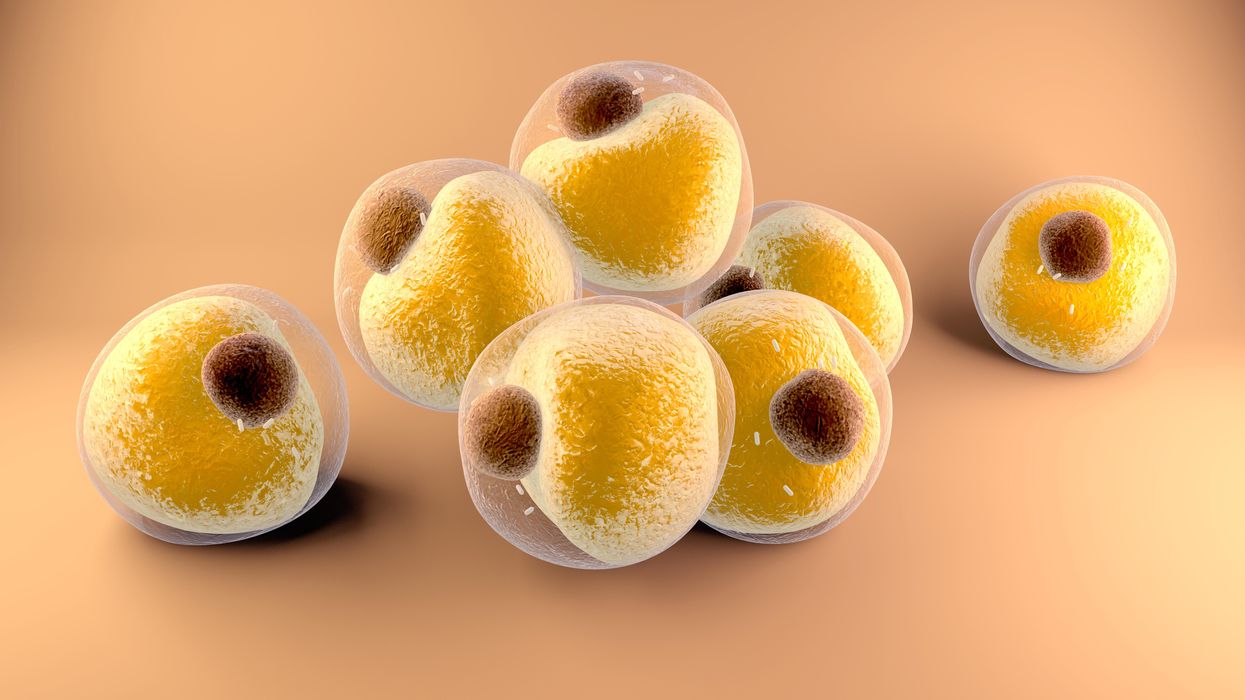

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.