So-Called “Puppy Mills” Are Not All As Bad As We Think, Pioneering Research Suggests

New research challenges the popular notion that all commercial breeding kennels are inhumane.

Candace Croney joined the faculty at Purdue University in 2011, thinking her job would focus on the welfare of livestock and poultry in Indiana. With bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees in animal sciences, her work until then had centered on sheep, cattle, and pigs. She'd even had the esteemed animal behaviorist Temple Grandin help shape her master's research project.

Croney's research has become the first of its kind in the world—and it's challenging our understanding of how dog breeding is being done.

Then came an email from a new colleague asking Croney to discuss animal welfare with some of Indiana's commercial dog breeders, the kind who produce large quantities of puppies for sale in pet stores.

"I didn't even know the term commercial breeders," Croney says. "I'd heard the term 'puppy millers.' That's pretty much what I knew."

She went to the first few kennels and braced herself for an upsetting experience. She's a dog lover who has fostered shelter mutts and owned one, and she'd seen the stories: large-scale breeders being called cruel and evil, lawmakers trying to ban the sale of commercially bred puppies, and constant encouragement to rescue a dog instead of paying into a greedy, heartless "puppy mill" industry.

But when she got to the kennels, she was surprised. While she encountered a number of things she didn't like about the infrastructure at the older facilities—a lack of ventilation, a lot of noise, bad smells—most of the dogs themselves were clean. The majority didn't have physical problems. No open sores. No battered bodies. Nothing like what she'd seen online.

But still, the way the dogs acted gave her pause.

"Things were, in many regards, better than I thought they would be," Croney says. "Google told me the dogs would be physically a mess, and they weren't, but behaviorally, things were jumping out at me."

While she did note that some of the breeders had play yards for their pups, a number of the dogs feared new people and things like leashes because they hadn't been exposed to enough of them. Some of the dogs also seemed to lack adequate toys, activities, and games to keep them mentally and physically stimulated.

But she was there strictly as a representative of the university to ask questions and offer feedback, no more or less. A few times, she says, she felt like the breeders wanted her to endorse what they were doing, "and I immediately got my back up about that. I did not want my name used to validate things that I could tell I didn't agree with. It was uncomfortable from that perspective."

After sharing the animal-welfare information her colleague had requested, Croney figured that was that. She never expected to be in a commercial kennel again. But six months later, her phone rang. Some of the people she'd met were involved in legislative lobbying, and they were trying to write welfare standards for Indiana's commercial breeders to follow.

In the continuing battle over what is, and is not, a "puppy mill," they wanted somebody with a strong research background to set a baseline standard, somebody who would actually bring objectivity to the breeder-activist conflict without being on one side or the other.

In other words, they wanted Croney's help to figure out not only appropriate enclosure sizes, but also requirements for socialization and enrichment activities—stimulation she knew the dogs desperately needed.

"I thought, crap, how am I not going to help?" she recalls. "And they said, 'Well how long will that take? A couple of weeks? A month?'"

Dr. Croney with Theo, whom she calls "a beloved family member of our research team."

(Photo credit: Purdue University/Vincent Walter)

Six years later, Croney's research remains ongoing. It has become the first of its kind in the world—and it's challenging our understanding of how dog breeding is being done, and how it could and should be done for years to come.

How We Got Here

Americans have been breeding pet dogs in large-scale kennels since World War II. The federal standard that regulates those kennels is the Animal Welfare Act, which President Johnson signed into law in 1966. Back then, people thought it was OK to treat dogs a lot differently than they do today. The law has been updated, but it still allows a dog the size of a Beagle to be kept in a cage the size of a dishwasher all day, every day because for some dogs, when the law was written, having a cage that size meant an improvement in living conditions.

Countless commercial breeders, who are regularly inspected under the Animal Welfare Act, have long believed that as long as they followed the law, they were doing things right. And they've seen sales for their puppies go up and up over the years. About 38 percent of U.S. households now own one or more dogs, the highest rate since the American Veterinary Medical Association began measuring the statistic in 1982.

Consumers now demand eight million dogs per year, which has reinforced breeders' beliefs that despite what activists shout at protests, the breeders are actually running businesses the public supports. As one Ohio commercial breeder—long decried by activists as a "puppy mill" owner—told The Washington Post in 2016, "This is a customer-driven industry. If we weren't satisfying the customer, we'd starve to death. I've never seen prices like the ones we're seeing now, in my whole career."

That breeder, though, is also among leading industry voices who say they understand that public perception of what's acceptable and what's not in a breeding kennel has changed. Regardless of what the laws are, they say, kennels must change along with the public's wishes if the commercial breeding industry is going to survive. The question is how, exactly, to move from the past to the future, at a time when demands for change have reached a fever pitch.

"The Animal Welfare Act, that was gospel. It meant you were taking care of dogs," says Bob Vetere, former head of the American Pet Products Association and now chairman of the Pet Leadership Council. "That was, what, 40 years ago? Things have evolved. People understand much more since then—and back then, there were maybe 20 million dogs in the country. Now, there's 90 million. It's that dramatic. People love their dogs, and everybody is going to get one."

Vetere became an early supporter of Croney's research, which, unbelievably, became the first ever to focus on what it actually means to run a good commercial breeding kennel. At the start of her research, Croney found that the scientific literature underpinning many existing laws and opinions was not just lacking, but outright nonexistent.

"We kept finding it over and over," she says of the literature gaps, citing common but uninformed beliefs about appropriate kennel size as just one example. "I can't find any research about how much space they're supposed to have. People said, 'Yeah, we had a meeting and a bunch of people made some recommendations.'"

She started filling in the research gaps with her team at Purdue, building relationships with dog breeders until she had more than 100 kennels letting her methodically figure out what was actually working for the dogs.

"The measurable successes in animal welfare over the past 50 years began from a foundation in science."

Creating Standards from Scratch

Other industry players soon took notice. One was Ed Sayres, who had served as CEO of the ASPCA for nearly a decade before turning his attention to lobbying efforts regarding the "puppy mill" issue. He recognized that what Croney was doing for commercial breeding mirrored the early work researchers started a half-century ago in the effort that led to better shelters all across America today.

"The measurable successes in animal welfare over the past 50 years began from a foundation in science," Sayres says. "Whether it was the transition to more humane euthanasia methods or how to manage dog and cat overpopulation, we found success from rigorous examination of facts and emerging science."

Sayres, Vetere, and others began pushing for the industry to support Croney's work, moving the goalposts beyond Indiana to the entire United States.

"If you don't have commercial breeding, you have people importing dogs from overseas with no restrictions, or farming in their backyards to make money," Vetere says. "You need commercial breeders with standards—and that's what Candace is trying to create, those standards."

Croney ended up with a $900,000 grant from three industry organizations: the World Pet Association, Pet Food Institute, and the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council. With their support, she created a nationwide program called Canine Care Certified, like a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for a kennel. The program focuses on outcome-based standards, meaning she looks at what the dogs tell her about how well they are doing through their health and behavior. For the most part, beyond baseline requirements, the program lets a breeder achieve those goals in whatever ways work for the dogs.

The approach is different from many legislative efforts, with laws stating a cage must be made three feet larger to be considered humane. Instead, Croney walks through kennels with breeders and points out, for instance, which puppies in a litter seem to be shy or fearful, and then teaches the breeders how to give those puppies better socialization. She helps the breeders find ways to introduce dogs to strangers and objects like umbrellas that may not be part of regular kennel life, but will need to become familiar when the breeding dog retires and gets adopted into a home as a pet. She helps breeders understand that dogs need mental as well as physical stimulation, whether it comes from playing with balls and toys or running up and down slides.

The breeders can't learn fast enough, Croney says, and she remains stunned at how they constantly ask for more information—an attitude that made her stop using the term "puppy mill" to describe them at all.

"Now, full disclosure: Given that all of these kennels had volunteered, the odds were that we were seeing a skewed population, and that it skewed positive," she says. "But if you read what was in the media at the time, we shouldn't have been able to find any. We're told that all these kennels are terrible. Clearly, it was possible to get a positive outcome."

To Buy or Not to Buy?

Today, she says, she's shocked at how quickly some of the kennels have improved. Facilities that appalled her at first sight now have dogs greeting people with wagging tails.

"Not only would I get a dog from them, but would I put my dog there in that kennel temporarily? Yeah, I would."

"The most horrifying thing I learned was that some of these people weren't doing what I'd like to see, not because they didn't care or only wanted money, but because nobody had ever told them," she says. "As it turned out, they didn't know any different, and no one would help them."

For Americans who want to know whether it's OK to get a commercially bred puppy, Croney says she thinks about her own dogs. When she started working with the breeders, there were plenty of kennels that, she says, she would not have wanted to patronize. But now she's changing her mind about more and more of them.

"I'm just speaking as somebody who loves dogs and wants to make sure I'm not subsidizing anything inhumane or cruel," she says. "Not only would I get a dog from them, but would I put my dog there in that kennel temporarily? Yeah, I would."

She says the most important thing is for consumers to find out how a pup was raised, and how the pup's parents were raised. As with most industries, commercial breeders run the gamut, from barely legal to above and beyond.

Not everyone agrees with Croney's take on the situation, or with her approach to improving commercial breeding kennels. In its publication "Puppy Mills and the Animal Welfare Act," the Humane Society of the United States writes that while Croney's Canine Care Certified program supports "common areas of agreement" with animal-welfare lobbyists, her work has been funded by the pet industry—suggesting that it's impure—and a voluntary program is not enough to incentivize breeders to improve.

New laws, the Humane Society states, must be enacted to impose change: "Many commercial dog breeding operators will not raise their standards voluntarily, and even if they were to agree to do so it is not clear whether there would be any independent mechanism for enforcement or transparency for the public's sake. ... The logical conclusion is that improved standards must be codified."

Croney says that type of attitude has long created resentment between breeders and animal-welfare activists, as opposed to actual kennel improvements. Both sides have a point; for years, there have been examples of bottom-of-the-barrel kennels that changed their ways or shut down only after regulators smacked them with violations, or after lawmakers raised operating standards in ways that required improvements for the kennels to remain legally in business.

At the same time, though, powerful organizations including the Humane Society—which had revenue of more than $165 million in 2018 alone—have routinely pushed for bans on stores that sell commercially bred puppies, and have decried "puppy mills" in marketing and fund-raising literature, without offering financial grants or educational programs to kennels that are willing to improve.

Croney believes that the reflexive demonization of all commercial breeders is a mistake. Change is more effective, she says, when breeders "want to do better, want to learn, want to grow, and you treat them as advocates and allies in doing something good for animal welfare, as opposed to treating them like they're your enemies."

"If you're watching undercover videos about people treating animals in bad ways, I'm telling you, change is happening."

She adds that anyone who says all commercial breeders are "puppy mills" needs to take a look at the kennels she's seen and the changes her work has brought—and is continuing to bring.

"The ones we work with are working really, really hard to improve and open their doors so that if somebody wants to get a dog from them, they can be assured that those dogs were treated with a level of care and compassion that wasn't there five or 10 years ago, but that is there now and will be better in a year and will be much better in five years," she says. "If you're watching undercover videos about people treating animals in bad ways, I'm telling you, change is happening. It is so much better than people realize, and it continues to get even better yet."

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

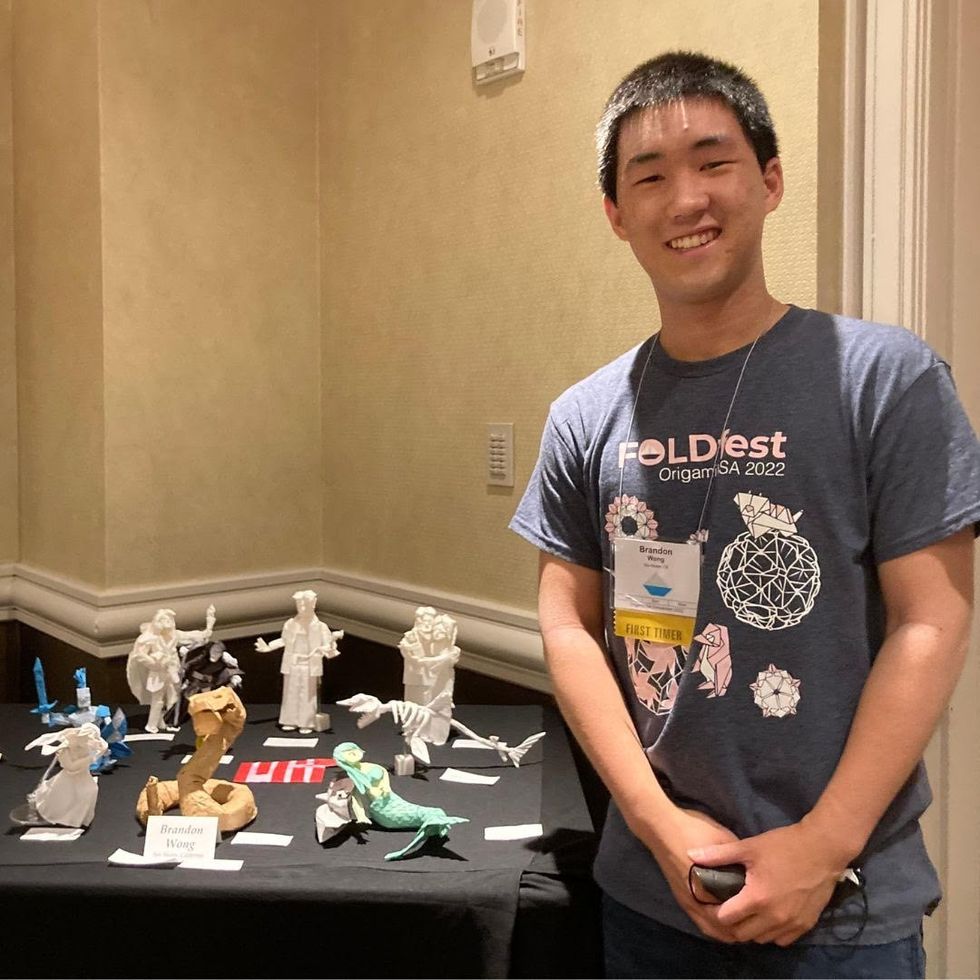

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”