Regenerative medicine has come a long way, baby

After a cloned baby sheep, what started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

The field of regenerative medicine had a shaky start. In 2002, when news spread about the first cloned animal, Dolly the sheep, a raucous debate ensued. Scary headlines and organized opposition groups put pressure on government leaders, who responded by tightening restrictions on this type of research.

Fast forward to today, and regenerative medicine, which focuses on making unhealthy tissues and organs healthy again, is rewriting the code to healing many disorders, though it’s still young enough to be considered nascent. What started as one of the most controversial areas in medicine is now promising to transform it.

Progress in the lab has addressed previous concerns. Back in the early 2000s, some of the most fervent controversy centered around somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the process used by scientists to produce Dolly. There was fear that this technique could be used in humans, with possibly adverse effects, considering the many medical problems of the animals who had been cloned.

But today, scientists have discovered better approaches with fewer risks. Pioneers in the field are embracing new possibilities for cellular reprogramming, 3D organ printing, AI collaboration, and even growing organs in space. It could bring a new era of personalized medicine for longer, healthier lives - while potentially sparking new controversies.

Engineering tissues from amniotic fluids

Work in regenerative medicine seeks to reverse damage to organs and tissues by culling, modifying and replacing cells in the human body. Scientists in this field reach deep into the mechanisms of diseases and the breakdowns of cells, the little workhorses that perform all life-giving processes. If cells can’t do their jobs, they take whole organs and systems down with them. Regenerative medicine seeks to harness the power of healthy cells derived from stem cells to do the work that can literally restore patients to a state of health—by giving them healthy, functioning tissues and organs.

Modern-day regenerative medicine takes its origin from the 1998 isolation of human embryonic stem cells, first achieved by John Gearhart at Johns Hopkins University. Gearhart isolated the pluripotent cells that can differentiate into virtually every kind of cell in the human body. There was a raging controversy about the use of these cells in research because at that time they came exclusively from early-stage embryos or fetal tissue.

Back then, the highly controversial SCNT cells were the only way to produce genetically matched stem cells to treat patients. Since then, the picture has changed radically because other sources of highly versatile stem cells have been developed. Today, scientists can derive stem cells from amniotic fluid or reprogram patients’ skin cells back to an immature state, so they can differentiate into whatever types of cells the patient needs.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

The ethical debate has been dialed back and, in the last few decades, the field has produced important innovations, spurring the development of whole new FDA processes and categories, says Anthony Atala, a bioengineer and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Atala and a large team of researchers have pioneered many of the first applications of 3D printed tissues and organs using cells developed from patients or those obtained from amniotic fluid or placentas.

His lab, considered to be the largest devoted to translational regenerative medicine, is currently working with 40 different engineered human tissues. Sixteen of them have been transplanted into patients. That includes skin, bladders, urethras, muscles, kidneys and vaginal organs, to name just a few.

These achievements are made possible by converging disciplines and technologies, such as cell therapies, bioengineering, gene editing, nanotechnology and 3D printing, to create living tissues and organs for human transplants. Atala is currently overseeing clinical trials to test the safety of tissues and organs engineered in the Wake Forest lab, a significant step toward FDA approval.

In the context of medical history, the field of regenerative medicine is progressing at a dizzying speed. But for those living with aggressive or chronic illnesses, it can seem that the wheels of medical progress grind slowly.

“It’s never fast enough,” Atala says. “We want to get new treatments into the clinic faster, but the reality is that you have to dot all your i’s and cross all your t’s—and rightly so, for the sake of patient safety. People want predictions, but you can never predict how much work it will take to go from conceptualization to utilization.”

As a surgeon, he also treats patients and is able to follow transplant recipients. “At the end of the day, the goal is to get these technologies into patients, and working with the patients is a very rewarding experience,” he says. Will the 3D printed organs ever outrun the shortage of donated organs? “That’s the hope,” Atala says, “but this technology won’t eliminate the need for them in our lifetime.”

New methods are out of this world

Jeanne Loring, another pioneer in the field and director of the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, says that investment in regenerative medicine is not only paying off, but is leading to truly personalized medicine, one of the holy grails of modern science.

This is because a patient’s own skin cells can be reprogrammed to become replacements for various malfunctioning cells causing incurable diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, macular degeneration and Parkinson’s. If the cells are obtained from a source other than the patient, they can be rejected by the immune system. This means that patients need lifelong immunosuppression, which isn’t ideal. “With Covid,” says Loring, “I became acutely aware of the dangers of immunosuppression.” Using the patient’s own cells eliminates that problem.

Microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, Loring's own cells have been sent to the ISS for study.

Loring has a special interest in neurons, or brain cells that can be developed by manipulating cells found in the skin. She is looking to eventually treat Parkinson’s disease using them. The manipulated cells produce dopamine, the critical hormone or neurotransmitter lacking in the brains of patients. A company she founded plans to start a Phase I clinical trial using cell therapies for Parkinson’s soon, she says.

This is the culmination of many years of basic research on her part, some of it on her own cells. In 2007, Loring had her own cells reprogrammed, so there’s a cell line that carries her DNA. “They’re just like embryonic stem cells, but personal,” she said.

Loring has another special interest—sending immature cells into space to be studied at the International Space Station. There, microgravity conditions make it easier for the cells to form three-dimensional structures, which could more easily lead to the growing of whole organs. In fact, her own cells have been sent to the ISS for study. “My colleagues and I have completed four missions at the space station,” she says. “The last cells came down last August. They were my own cells reprogrammed into pluripotent cells in 2009. No one else can say that,” she adds.

Future controversies and tipping points

Although the original SCNT debate has calmed down, more controversies may arise, Loring thinks.

One of them could concern growing synthetic embryos. The embryos are ultimately derived from embryonic stem cells, and it’s not clear to what stage these embryos can or will be grown in an artificial uterus—another recent invention. The science, so far done only in animals, is still new and has not been widely publicized but, eventually, “People will notice the production of synthetic embryos and growing them in an artificial uterus,” Loring says. It’s likely to incite many of the same reactions as the use of embryonic stem cells.

Bernard Siegel, the founder and director of the Regenerative Medicine Foundation and executive director of the newly formed Healthspan Action Coalition (HSAC), believes that stem cell science is rapidly approaching tipping point and changing all of medical science. (For disclosure, I do consulting work for HSAC). Siegel says that regenerative medicine has become a new pillar of medicine that has recently been fast-tracked by new technology.

Artificial intelligence is speeding up discoveries and the convergence of key disciplines, as demonstrated in Atala’s lab, which is creating complex new medical products that replace the body’s natural parts. Just as importantly, those parts are genetically matched and pose no risk of rejection.

These new technologies must be regulated, which can be a challenge, Siegel notes. “Cell therapies represent a challenge to the existing regulatory structure, including payment, reimbursement and infrastructure issues that 20 years ago, didn’t exist.” Now the FDA and other agencies are faced with this revolution, and they’re just beginning to adapt.

Siegel cited the 2021 FDA Modernization Act as a major step. The Act allows drug developers to use alternatives to animal testing in investigating the safety and efficacy of new compounds, loosening the agency’s requirement for extensive animal testing before a new drug can move into clinical trials. The Act is a recognition of the profound effect that cultured human cells are having on research. Being able to test drugs using actual human cells promises to be far safer and more accurate in predicting how they will act in the human body, and could accelerate drug development.

Siegel, a longtime veteran and founding father of several health advocacy organizations, believes this work helped bring cell therapies to people sooner rather than later. His new focus, through the HSAC, is to leverage regenerative medicine into extending not just the lifespan but the worldwide human healthspan, the period of life lived with health and vigor. “When you look at the HSAC as a tree,” asks Siegel, “what are the roots of that tree? Stem cell science and the huge ecosystem it has created.” The study of human aging is another root to the tree that has potential to lengthen healthspans.

The revolutionary science underlying the extension of the healthspan needs to be available to the whole world, Siegel says. “We need to take all these roots and come up with a way to improve the life of all mankind,” he says. “Everyone should be able to take advantage of this promising new world.”

As We Wait for a Vaccine, Scientists Work to Scale Up the Best COVID-19 Antibodies to Give New Patients

In this illustration of immune defense, Y-shaped proteins called antibodies attack a virus.

When we get sick, our immune system sends its soldier cells to the battlefield. Called B-cells, they "examine" the foreign particles that shouldn't be in our bloodstream—and start producing the antibodies, the proteins to neutralize the invaders.

To screen the antibodies, scientists have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

The better these antibodies are at neutralizing the pathogen, the faster we recover.

The antibodies acquired from COVID-19 survivors already showed promise in treating other patients, but because they must be obtained from people, generating a regular supply is not feasible. To close the gap, researchers are trying to identify the B-cells that make the best antibodies—and then farm them in laboratories at scale.

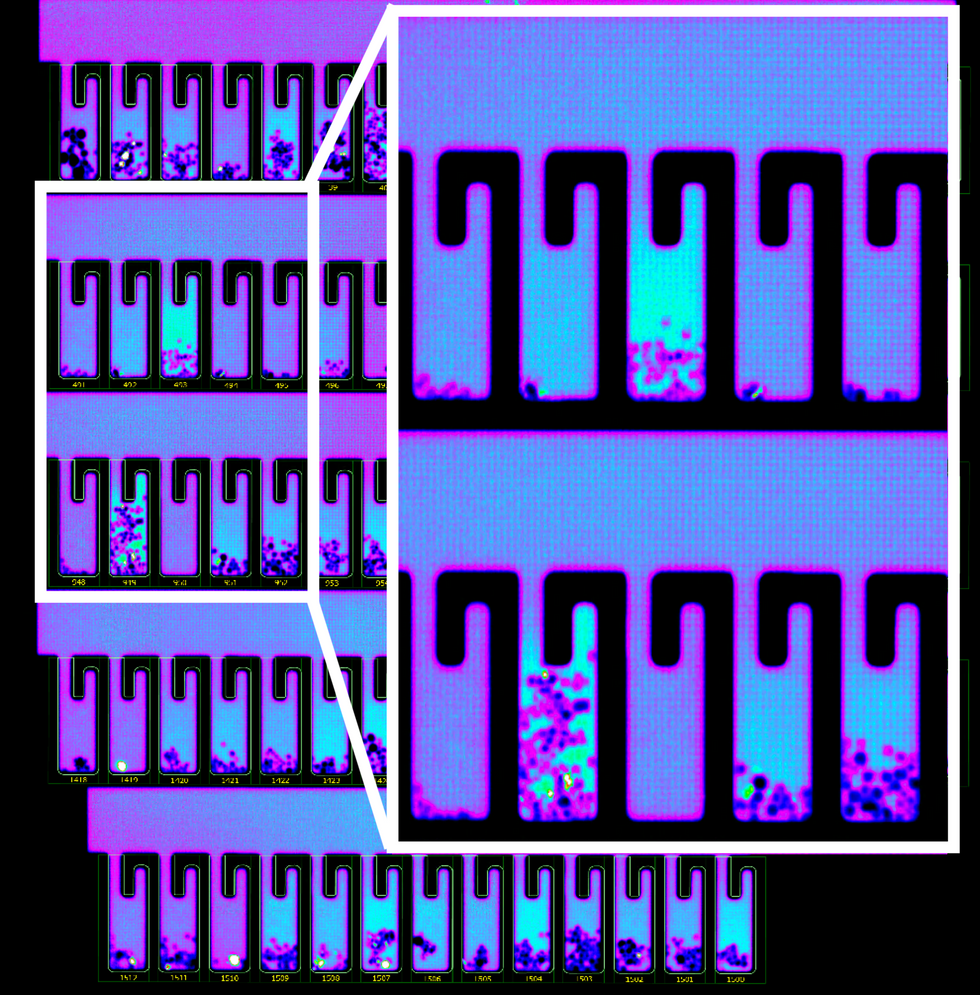

Scientists at Berkley Lights, a biotechnology company in California, have been screening B-cells from recovered patients and testing the antibodies they release for virus-neutralizing abilities. To screen the antibodies, scientists there have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

So how does it work? First, the individual B-cells are placed into microscopic chambers called nano-pens, where they secrete the antibodies. Once released, the antibodies are flushed over tiny beads that have bits of the viral particles attached to them, along with special molecules that can emit fluorescent light.

"When an antibody binds to the bead, we see a bright light on the bead," explains John Proctor, the company's senior vice president of antibody therapeutics. "So we can identify which cells are making the antibodies."

Then the antibodies are tested for their ability to counteract the coronavirus's spike proteins, which the virus uses to break into our cells. Not all antibodies are equally good at this crucial defense move—some can block only parts of the virus's machinery, while others can neutralize it completely. Proctor and his colleagues are looking for the latter.

Once scientists identify the best performing B-cells, they crack the cells open—or in scientific terms "lyse" them—and extract the genetic instructions for making the antibodies. As it turns out, B-cells aren't very efficient at pumping out massive amounts of antibodies, so scientists insert these genetic instructions into a different, more prolific type of cell.

Named Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells or CHO, these cells are commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry because they can generate therapeutic proteins en masse. Under the right nutrient conditions, which include a lot of sugar, CHO cells can keep making the antibodies at commercial levels. "They are engineered to operate in very large bioreactors," Proctor explains.

While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours.

Berkeley Lights' technology has already been used to screen the antibodies of recovered patients from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In another example, a biotech company GenScript ProBio used the platform to screen mice engineered to have human antibodies for the coronavirus.

In addition to its small, lab-on-a-chip size, Berkeley Lights' system allows scientists to greatly speed up the screening process. While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours. "We only need one B-cell per pen and a couple of beads to see that fluorescent signal," Proctor says. "It is a more advanced way to process and analyze cells, and that level of sensitivity is unique to our technology."

B-cells secreting antibodies inside the Berkeley Lights Beacon System Nano-Pens.

While vaccines are likely to take months to develop and test, antibodies might arrive to the battleground sooner. With the extremely limited treatment options for COVID-19, antibody-based therapeutics can potentially bridge this gap.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

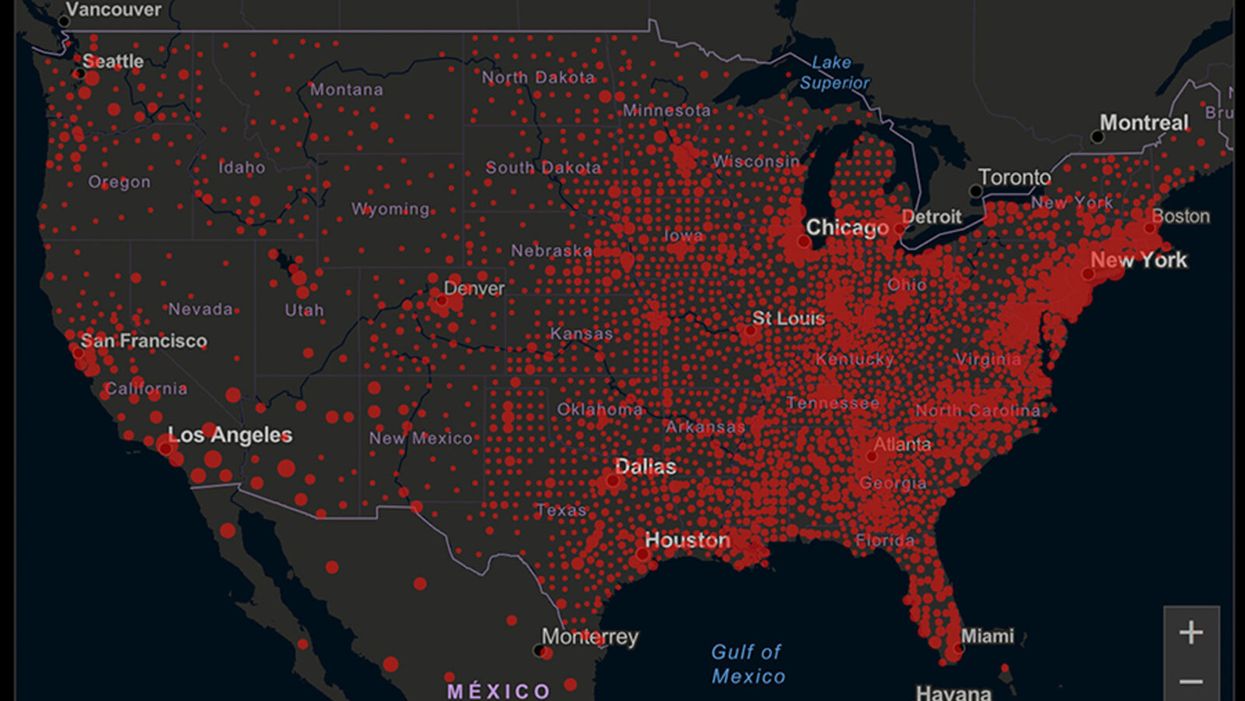

A map of cumulative known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., as of June 12th, 2020.

Have you felt a bit like an armchair epidemiologist lately? Maybe you've been poring over coronavirus statistics on your county health department's website or on the pages of your local newspaper.

If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

You're likely to find numbers and charts but little guidance about how to interpret them, let alone use them to make day-to-day decisions about pandemic safety precautions.

Enter the gurus. We asked several experts to provide guidance for laypeople about how to navigate the numbers. Here's a look at several common COVID-19 statistics along with tips about how to understand them.

Case Counts: Consider the Context

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in American counties is widely available. Local and state health departments should provide them online, or you can easily look them up at The New York Times' coronavirus database. However, you need to be cautious about interpreting them.

"Case counts are the obvious numbers to look at. But they're probably the hardest thing to sort out," said Dr. Jeff Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

That's because case counts by themselves aren't a good window into how the coronavirus is affecting your community since they rely on testing. And testing itself varies widely from day to day and community to community.

"The more testing that's done, the more infections you'll pick up," explained Dr. F. Perry Wilson, a physician at Yale University. The numbers can also be thrown off when tests are limited to certain groups of people.

"If the tests are being mostly given to people with a high probability of having been infected -- for example, they have had symptoms or work in a high-risk setting -- then we expect lots of the tests to be positive. But that doesn't tell us what proportion of the general public is likely to have been infected," said Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

These Stats Are More Meaningful

According to Dr. Wilson, it's more useful to keep two other statistics in mind: the number of COVID tests that are being performed in your community and the percentage that turn up positive, showing that people have the disease. (These numbers may or may not be available locally. Check the websites of your community's health department and local news media outlets.)

If the number of people being tested is going up, but the percentage of positive tests is going down, Dr. Wilson said, that's a good sign. But if both numbers are going up – the number of people tested and the percentage of positive results – then "that's a sign that there are more infections burning in the community."

It's especially worrisome if the percentage of positive cases is growing compared to previous days or weeks, he said. According to him, that's a warning of a "high-risk situation."

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at University of California at San Francisco, offered this tip: If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

There's one more caveat about case counts. It takes an average of a week for someone to be infected with COVID-19, develop symptoms, and get tested, Dr. Rutherford said. It can take an additional several days for those test results to be reported to the county health department. This means that case numbers don't represent infections happening right now, but instead are a picture of the state of the pandemic more than a week ago.

Hospitalizations: Focus on Current Statistics

You should be able to find numbers about how many people in your community are currently hospitalized – or have been hospitalized – with diagnoses of COVID-19. But experts say these numbers aren't especially revealing unless you're able to see the number of new hospitalizations over time and track whether they're rising or falling. This number often isn't publicly available, however.

If new hospitalizations are increasing, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

And there's an important caveat: "The problem with hospitalizations is that they do lag," UC San Francisco's Dr. Martin said, since it takes time for someone to become ill enough to need to be hospitalized. "They tell you how much virus was being transmitted in your community 2 or 2.5 weeks ago."

Also, he said, people should be cautious about comparing new hospitalization rates between communities unless they're adjusted to account for the number of more-vulnerable older people.

Still, if new hospitalizations are increasing, he said, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

Deaths: They're an Even More Delayed Headline

Cable news networks obsessively track the number of coronavirus deaths nationwide, and death counts for every county in the country are available online. Local health departments and media websites may provide charts tracking the growth in deaths over time in your community.

But while death rates offer insight into the disease's horrific toll, they're not useful as an instant snapshot of the pandemic in your community because severely ill patients are typically sick for weeks. Instead, think of them as a delayed headline.

"These numbers don't tell you what's happening today. They tell you how much virus was being transmitted 3-4 weeks ago," Dr. Martin said.

'Reproduction Value': It May Be Revealing

You're not likely to find an available "reproduction value" for your community, but it is available for your state and may be useful.

A reproduction value, also known as R0 or R-naught, "tells us how many people on average we expect will be infected from a single case if we don't take any measures to intervene and if no one has been infected before," said Boston University's Murray.

As The New York Times explained, "R0 is messier than it might look. It is built on hard science, forensic investigation, complex mathematical models — and often a good deal of guesswork. It can vary radically from place to place and day to day, pushed up or down by local conditions and human behavior."

It may be impossible to find the R0 for your community. However, a website created by data specialists is providing updated estimates of a related number -- effective reproduction number, or Rt – for each state. (The R0 refers to how infectious the disease is in general and if precautions aren't taken. The Rt measures its infectiousness at a specific time – the "t" in Rt.) The site is at rt.live.

"The main thing to look at is whether the number is bigger than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently growing in your area, or smaller than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently decreasing in your area," Murray said. "It's also important to remember that this number depends on the prevention measures your community is taking. If the Rt is estimated to be 0.9 in your area and you are currently under lockdown, then to keep it below 1 you may need to remain under lockdown. Relaxing the lockdown could mean that Rt increases above 1 again."

"Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing."

Keep in mind that you can still become infected even if an outbreak in your community appears to be slowing. Low risk doesn't mean no risk.

Putting It All Together: Why the Numbers Matter

So you've reviewed COVID-19 statistics in your community. Now what?

Dr. Wilson suggests using the data to remind yourself that the coronavirus pandemic "is still out there. You need to take it seriously and continue precautions," he said. "Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing. 'My state is doing well, no one I know is sick, is it time to have a dinner party?' No."

He also recommends that laypeople avoid tracking COVID-19 statistics every day. "Check in once a week or twice a month to see how things are going," he suggested. "Don't stress too much. Just let it remind you to put that mask on before you get out of your car [and are around others]."