Researchers Are Testing a New Stem Cell Therapy in the Hopes of Saving Millions from Blindness

NIH researchers in Kapil Bharti's lab work toward the development of induced pluripotent stem cells to treat dry age-related macular degeneration.

Of all the infirmities of old age, failing sight is among the cruelest. It can mean the end not only of independence, but of a whole spectrum of joys—from gazing at a sunset or a grandchild's face to reading a novel or watching TV.

The Phase 1 trial will likely run through 2022, followed by a larger Phase 2 trial that could last another two or three years.

The leading cause of vision loss in people over 55 is age-related macular degeneration, or AMD, which afflicts an estimated 11 million Americans. As photoreceptors in the macula (the central part of the retina) die off, patients experience increasingly severe blurring, dimming, distortions, and blank spots in one or both eyes.

The disorder comes in two varieties, "wet" and "dry," both driven by a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. It begins when deposits of cellular debris accumulate beneath the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)—a layer of cells that nourish and remove waste products from the photoreceptors above them. In wet AMD, this process triggers the growth of abnormal, leaky blood vessels that damage the photoreceptors. In dry AMD, which accounts for 80 to 90 percent of cases, RPE cells atrophy, causing photoreceptors to wither away. Wet AMD can be controlled in about a quarter of patients, usually by injections of medication into the eye. For dry AMD, no effective remedy exists.

Stem Cells: Promise and Perils

Over the past decade, stem cell therapy has been widely touted as a potential treatment for AMD. The idea is to augment a patient's ailing RPE cells with healthy ones grown in the lab. A few small clinical trials have shown promising results. In a study published in 2018, for example, a University of Southern California team cultivated RPE tissue from embryonic stem cells on a plastic matrix and transplanted it into the retinas of four patients with advanced dry AMD. Because the trial was designed to test safety rather than efficacy, lead researcher Amir Kashani told a reporter, "we didn't expect that replacing RPE cells would return a significant amount of vision." Yet acuity improved substantially in one recipient, and the others regained their lost ability to focus on an object.

Therapies based on embryonic stem cells, however, have two serious drawbacks: Using fetal cell lines raises ethical issues, and such treatments require the patient to take immunosuppressant drugs (which can cause health problems of their own) to prevent rejection. That's why some experts favor a different approach—one based on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Such cells, first produced in 2006, are made by returning adult cells to an undifferentiated state, and then using chemicals to reprogram them as desired. Treatments grown from a patient's own tissues could sidestep both hurdles associated with embryonic cells.

At least hypothetically. Today, the only stem cell therapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are umbilical cord-derived products for various blood and immune disorders. Although scientists are probing the use of embryonic stem cells or iPSCs for conditions ranging from diabetes to Parkinson's disease, such applications remain experimental—or fraudulent, as a growing number of patients treated at unlicensed "stem cell clinics" have painfully learned. (Some have gone blind after receiving bogus AMD therapies at those facilities.)

Last December, researchers at the National Eye Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, began enrolling patients with dry AMD in the country's first clinical trial using tissue grown from the patients' own stem cells. Led by biologist Kapil Bharti, the team intends to implant custom-made RPE cells in 12 recipients. If the effort pans out, it could someday save the sight of countless oldsters.

That, however, is what's technically referred to as a very big "if."

The First Steps

Bharti's trial is not the first in the world to use patient-derived iPSCs to treat age-related macular degeneration. In 2013, Japanese researchers implanted such cells into the eyes of a 77-year-old woman with wet AMD; after a year, her vision had stabilized, and she no longer needed injections to keep abnormal blood vessels from forming. A second patient was scheduled for surgery—but the procedure was canceled after the lab-grown RPE cells showed signs of worrisome mutations. That incident illustrates one potential problem with using stem cells: Under some circumstances, the cells or the tissue they form could turn cancerous.

"The knowledge and expertise we're gaining can be applied to many other iPSC-based therapies."

Bharti and his colleagues have gone to great lengths to avoid such outcomes. "Our process is significantly different," he told me in a phone interview. His team begins with patients' blood stem cells, which appear to be more genomically stable than the skin cells that the Japanese group used. After converting the blood cells to RPE stem cells, his team cultures them in a single layer on a biodegradable scaffold, which helps them grow in an orderly manner. "We think this material gives us a big advantage," Bharti says. The team uses a machine-learning algorithm to identify optimal cell structure and ensure quality control.

It takes about six months for a patch of iPSCs to become viable RPE cells. When they're ready, a surgeon uses a specially-designed tool to insert the tiny structure into the retina. Within days, the scaffold melts away, enabling the transplanted RPE cells to integrate fully into their new environment. Bharti's team initially tested their method on rats and pigs with eye damage mimicking AMD. The study, published in January 2019 in Science Translational Medicine, found that at ten weeks, the implanted RPE cells continued to function normally and protected neighboring photoreceptors from further deterioration. No trace of mutagenesis appeared.

Encouraged by these results, Bharti began recruiting human subjects. The Phase 1 trial will likely run through 2022, followed by a larger Phase 2 trial that could last another two or three years. FDA approval would require an even larger Phase 3 trial, with a decision expected sometime between 2025 and 2028—that is, if nothing untoward happens before then. One unknown (among many) is whether implanted cells can thrive indefinitely under the biochemically hostile conditions of an eye with AMD.

"Most people don't have a sense of just how long it takes to get something like this to work, and how many failures—even disasters—there are along the way," says Marco Zarbin, professor and chair of Ophthalmology and visual science at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and co-editor of the book Cell-Based Therapy for Degenerative Retinal Diseases. "The first kidney transplant was done in 1933. But the first successful kidney transplant was in 1954. That gives you a sense of the time frame. We're really taking the very first steps in this direction."

Looking Ahead

Even if Bharti's method proves safe and effective, there's the question of its practicality. "My sense is that using induced pluripotent stem cells to treat the patient from whom they're derived is a very expensive undertaking," Zarbin observes. "So you'd have to have a very dramatic clinical benefit to justify that cost."

Bharti concedes that the price of iPSC therapy is likely to be high, given that each "dose" is formulated for a single individual, requires months to manufacture, and must be administered via microsurgery. Still, he expects economies of scale and production to emerge with time. "We're working on automating several steps of the process," he explains. "When that kicks in, a technician will be able to make products for 10 or 20 people at once, so the cost will drop proportionately."

Meanwhile, other researchers are pressing ahead with therapies for AMD using embryonic stem cells, which could be mass-produced to treat any patient who needs them. But should that approach eventually win FDA approval, Bharti believes there will still be room for a technique that requires neither fetal cell lines nor immunosuppression.

And not only for eye ailments. "The knowledge and expertise we're gaining can be applied to many other iPSC-based therapies," says the scientist, who is currently consulting with several companies that are developing such treatments. "I'm hopeful that we can leverage these approaches for a wide range of applications, whether it's for vision or across the body."

NEI launches iPS cell therapy trial for dry AMD

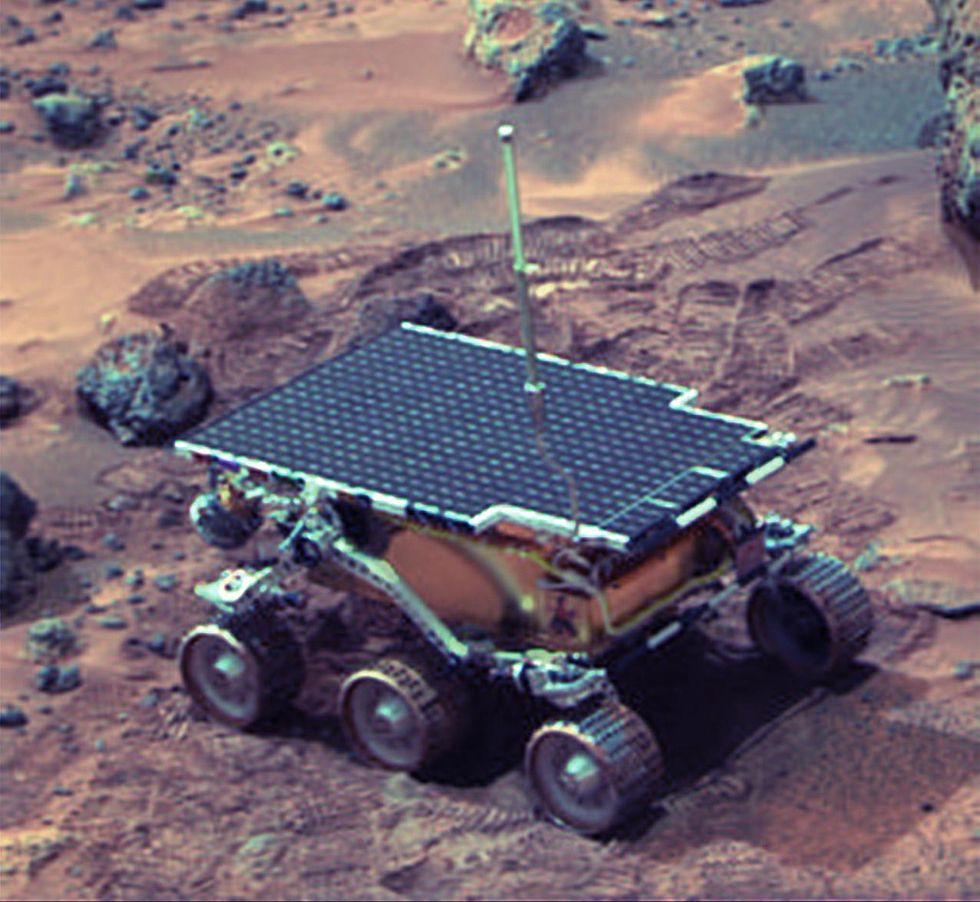

Donna Shirley pictured at her home in Tulsa, with a model of the Sojourner rover she was in charge of that explored Mars.

When NASA's Perseverance rover landed successfully on Mars on February 18, 2021, calling it "one giant leap for mankind" – as Neil Armstrong said when he set foot on the moon in 1969 – would have been inaccurate. This year actually marked the fifth time the U.S. space agency has put a remote-controlled robotic exploration vehicle on the Red Planet. And it was a female engineer named Donna Shirley who broke new ground for women in science as the manager of both the Mars Exploration Program and the 30-person team that built Sojourner, the first rover to land on Mars on July 4, 1997.

For Shirley, the Mars Pathfinder mission was the climax of her 32-year career at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The Oklahoma-born scientist, who earned her Master's degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Southern California, saw her profile skyrocket with media appearances from CNN to the New York Times, and her autobiography Managing Martians came out in 1998. Now 79 and living in a Tulsa retirement community, she still embraces her status as a female pioneer.

"Periodically, I'll hear somebody say they got into the space program because of me, and that makes me feel really good," Shirley told Leaps.org. "I look at the mission control area, and there are a lot of women in there. I'm quite pleased I was able to break the glass ceiling."

Her $25-million, 25-pound microrover – powered by solar energy and designed to get rock samples and test soil chemistry for evidence of life – was named after Sojourner Truth, a 19th-century Black abolitionist and women's rights activist. Unlike Mars Pathfinder, Shirley didn't have to travel more than 131 million miles to reach her goal, but her path to scientific fame as a woman sometimes resembled an asteroid field.

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.NASA/JPL

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.NASA/JPLAs a high-IQ tomboy growing up in Wynnewood, Oklahoma (pop. 2,300), Shirley yearned to escape. She decided to become an engineer at age 10 and took flying lessons at 15. Her extraterrestrial aspirations were fueled by Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles and Arthur C. Clarke's The Sands of Mars. Yet when she entered the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1958, her freshman academic advisor initially told her: "Girls can't be engineers." She ignored him.

Years later, Shirley would combat such archaic thinking, succeeding at JPL with her creative, collaborative management style. "If you look at the literature, you'll find that teams that are either led by or heavily involved with women do better than strictly male teams," she noted.

However, her career trajectory stalled at OU. Burned out by her course load and distracted by a broken engagement to marry a fellow student, she switched her major to professional writing. After graduation, she applied her aeronautical background as a McDonnell Aircraft technical writer, but her boss, she says, harassed her and she faced gender-based hostility from male co-workers.

Returning to OU, Shirley finished off her engineering degree and became a JPL aerodynamist in 1966 after answering an ad in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. At first, she was the only female engineer among the research center's 2,000-odd engineers. She wore many hats, from designing planetary atmospheric entry vehicles to picking the launch date of November 4, 1973 for Mariner 10's mission to Venus and Mercury.

By the mid-1980's, she was managing teams that focused on robotics and Mars, delivering creative solutions when NASA budget cuts loomed. In 1989, the same year the Sojourner microrover concept was born, President George H.W. Bush announced his Space Exploration Initiative, including plans for a human mission to Mars by 2019.

That target, of course, wasn't attained, despite huge advances in technology and our understanding of the Martian environment. Today, Shirley believes humans could land on Mars by 2030. She became the founding director of the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle in 2004 after leaving NASA, and to this day, she enjoys checking out pop culture portrayals of Mars landings – even if they're not always accurate.

After the novel The Martian was published in 2011, which later was adapted into the hit film starring Matt Damon, Shirley phoned author Andy Weir: "You've got a major mistake in here. It says there's a storm that tries to blow the rocket over. But actually, the Mars atmosphere is so thin, it would never blow a rocket over!"

Fearlessly speaking her mind and seeking the stars helped Donna Shirley make history. However, a 2019 Washington Post story noted: "Women make up only about a third of NASA's workforce. They comprise just 28 percent of senior executive leadership positions and are only 16 percent of senior scientific employees." Whether it's traveling to Mars or trending toward gender equality, we've still got a long way to go.

Announcing March Event: "COVID Vaccines and the Return to Life: Part 1"

Leading medical and scientific experts will discuss the latest developments around the COVID-19 vaccines at our March 11th event.

EVENT INFORMATION

DATE:

Thursday, March 11th, 2021 at 12:30pm - 1:45pm EST

On the one-year anniversary of the global declaration of the pandemic, this virtual event will convene leading scientific and medical experts to discuss the most pressing questions around the COVID-19 vaccines. Planned topics include the effect of the new circulating variants on the vaccines, what we know so far about transmission dynamics post-vaccination, how individuals can behave post-vaccination, the myths of "good" and "bad" vaccines as more alternatives come on board, and more. A public Q&A will follow the expert discussion.

CONTACT:

kira@goodinc.com

LOCATION:

Zoom webinar

SPEAKERS:

Dr. Paul Offit speaking at Communicating Vaccine Science.

commons.wikimedia.orgDr. Paul Offit, M.D., is the director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in infectious diseases at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He is a co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine for infants, and he has lent his expertise to the advisory committees that review data on new vaccines for the CDC and FDA.

Dr. Monica Gandhi

UCSF Health

Dr. Monica Gandhi, M.D., MPH, is Professor of Medicine and Associate Division Chief (Clinical Operations/ Education) of the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine at UCSF/ San Francisco General Hospital.

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, FACP, FIDSA

Yale Medicine

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, is an infectious disease physician at Yale Medicine who treats COVID-19 patients and leads Yale's clinical studies around COVID-19. He ran Yale's trial of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

Dr. Eric Topol

Dr. Topol's Twitter

Dr. Eric Topol, M.D., is a cardiologist, scientist, professor of molecular medicine, and the director and founder of Scripps Research Translational Institute. He has led clinical trials in over 40 countries with over 200,000 patients and pioneered the development of many routinely used medications.

REGISTER NOW

This event is the first of a four-part series co-hosted by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.