Researchers Are Testing a New Stem Cell Therapy in the Hopes of Saving Millions from Blindness

NIH researchers in Kapil Bharti's lab work toward the development of induced pluripotent stem cells to treat dry age-related macular degeneration.

Of all the infirmities of old age, failing sight is among the cruelest. It can mean the end not only of independence, but of a whole spectrum of joys—from gazing at a sunset or a grandchild's face to reading a novel or watching TV.

The Phase 1 trial will likely run through 2022, followed by a larger Phase 2 trial that could last another two or three years.

The leading cause of vision loss in people over 55 is age-related macular degeneration, or AMD, which afflicts an estimated 11 million Americans. As photoreceptors in the macula (the central part of the retina) die off, patients experience increasingly severe blurring, dimming, distortions, and blank spots in one or both eyes.

The disorder comes in two varieties, "wet" and "dry," both driven by a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. It begins when deposits of cellular debris accumulate beneath the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)—a layer of cells that nourish and remove waste products from the photoreceptors above them. In wet AMD, this process triggers the growth of abnormal, leaky blood vessels that damage the photoreceptors. In dry AMD, which accounts for 80 to 90 percent of cases, RPE cells atrophy, causing photoreceptors to wither away. Wet AMD can be controlled in about a quarter of patients, usually by injections of medication into the eye. For dry AMD, no effective remedy exists.

Stem Cells: Promise and Perils

Over the past decade, stem cell therapy has been widely touted as a potential treatment for AMD. The idea is to augment a patient's ailing RPE cells with healthy ones grown in the lab. A few small clinical trials have shown promising results. In a study published in 2018, for example, a University of Southern California team cultivated RPE tissue from embryonic stem cells on a plastic matrix and transplanted it into the retinas of four patients with advanced dry AMD. Because the trial was designed to test safety rather than efficacy, lead researcher Amir Kashani told a reporter, "we didn't expect that replacing RPE cells would return a significant amount of vision." Yet acuity improved substantially in one recipient, and the others regained their lost ability to focus on an object.

Therapies based on embryonic stem cells, however, have two serious drawbacks: Using fetal cell lines raises ethical issues, and such treatments require the patient to take immunosuppressant drugs (which can cause health problems of their own) to prevent rejection. That's why some experts favor a different approach—one based on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Such cells, first produced in 2006, are made by returning adult cells to an undifferentiated state, and then using chemicals to reprogram them as desired. Treatments grown from a patient's own tissues could sidestep both hurdles associated with embryonic cells.

At least hypothetically. Today, the only stem cell therapies approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are umbilical cord-derived products for various blood and immune disorders. Although scientists are probing the use of embryonic stem cells or iPSCs for conditions ranging from diabetes to Parkinson's disease, such applications remain experimental—or fraudulent, as a growing number of patients treated at unlicensed "stem cell clinics" have painfully learned. (Some have gone blind after receiving bogus AMD therapies at those facilities.)

Last December, researchers at the National Eye Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, began enrolling patients with dry AMD in the country's first clinical trial using tissue grown from the patients' own stem cells. Led by biologist Kapil Bharti, the team intends to implant custom-made RPE cells in 12 recipients. If the effort pans out, it could someday save the sight of countless oldsters.

That, however, is what's technically referred to as a very big "if."

The First Steps

Bharti's trial is not the first in the world to use patient-derived iPSCs to treat age-related macular degeneration. In 2013, Japanese researchers implanted such cells into the eyes of a 77-year-old woman with wet AMD; after a year, her vision had stabilized, and she no longer needed injections to keep abnormal blood vessels from forming. A second patient was scheduled for surgery—but the procedure was canceled after the lab-grown RPE cells showed signs of worrisome mutations. That incident illustrates one potential problem with using stem cells: Under some circumstances, the cells or the tissue they form could turn cancerous.

"The knowledge and expertise we're gaining can be applied to many other iPSC-based therapies."

Bharti and his colleagues have gone to great lengths to avoid such outcomes. "Our process is significantly different," he told me in a phone interview. His team begins with patients' blood stem cells, which appear to be more genomically stable than the skin cells that the Japanese group used. After converting the blood cells to RPE stem cells, his team cultures them in a single layer on a biodegradable scaffold, which helps them grow in an orderly manner. "We think this material gives us a big advantage," Bharti says. The team uses a machine-learning algorithm to identify optimal cell structure and ensure quality control.

It takes about six months for a patch of iPSCs to become viable RPE cells. When they're ready, a surgeon uses a specially-designed tool to insert the tiny structure into the retina. Within days, the scaffold melts away, enabling the transplanted RPE cells to integrate fully into their new environment. Bharti's team initially tested their method on rats and pigs with eye damage mimicking AMD. The study, published in January 2019 in Science Translational Medicine, found that at ten weeks, the implanted RPE cells continued to function normally and protected neighboring photoreceptors from further deterioration. No trace of mutagenesis appeared.

Encouraged by these results, Bharti began recruiting human subjects. The Phase 1 trial will likely run through 2022, followed by a larger Phase 2 trial that could last another two or three years. FDA approval would require an even larger Phase 3 trial, with a decision expected sometime between 2025 and 2028—that is, if nothing untoward happens before then. One unknown (among many) is whether implanted cells can thrive indefinitely under the biochemically hostile conditions of an eye with AMD.

"Most people don't have a sense of just how long it takes to get something like this to work, and how many failures—even disasters—there are along the way," says Marco Zarbin, professor and chair of Ophthalmology and visual science at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and co-editor of the book Cell-Based Therapy for Degenerative Retinal Diseases. "The first kidney transplant was done in 1933. But the first successful kidney transplant was in 1954. That gives you a sense of the time frame. We're really taking the very first steps in this direction."

Looking Ahead

Even if Bharti's method proves safe and effective, there's the question of its practicality. "My sense is that using induced pluripotent stem cells to treat the patient from whom they're derived is a very expensive undertaking," Zarbin observes. "So you'd have to have a very dramatic clinical benefit to justify that cost."

Bharti concedes that the price of iPSC therapy is likely to be high, given that each "dose" is formulated for a single individual, requires months to manufacture, and must be administered via microsurgery. Still, he expects economies of scale and production to emerge with time. "We're working on automating several steps of the process," he explains. "When that kicks in, a technician will be able to make products for 10 or 20 people at once, so the cost will drop proportionately."

Meanwhile, other researchers are pressing ahead with therapies for AMD using embryonic stem cells, which could be mass-produced to treat any patient who needs them. But should that approach eventually win FDA approval, Bharti believes there will still be room for a technique that requires neither fetal cell lines nor immunosuppression.

And not only for eye ailments. "The knowledge and expertise we're gaining can be applied to many other iPSC-based therapies," says the scientist, who is currently consulting with several companies that are developing such treatments. "I'm hopeful that we can leverage these approaches for a wide range of applications, whether it's for vision or across the body."

NEI launches iPS cell therapy trial for dry AMD

A New Test Aims to Objectively Measure Pain. It Could Help Legitimate Sufferers Access the Meds They Need.

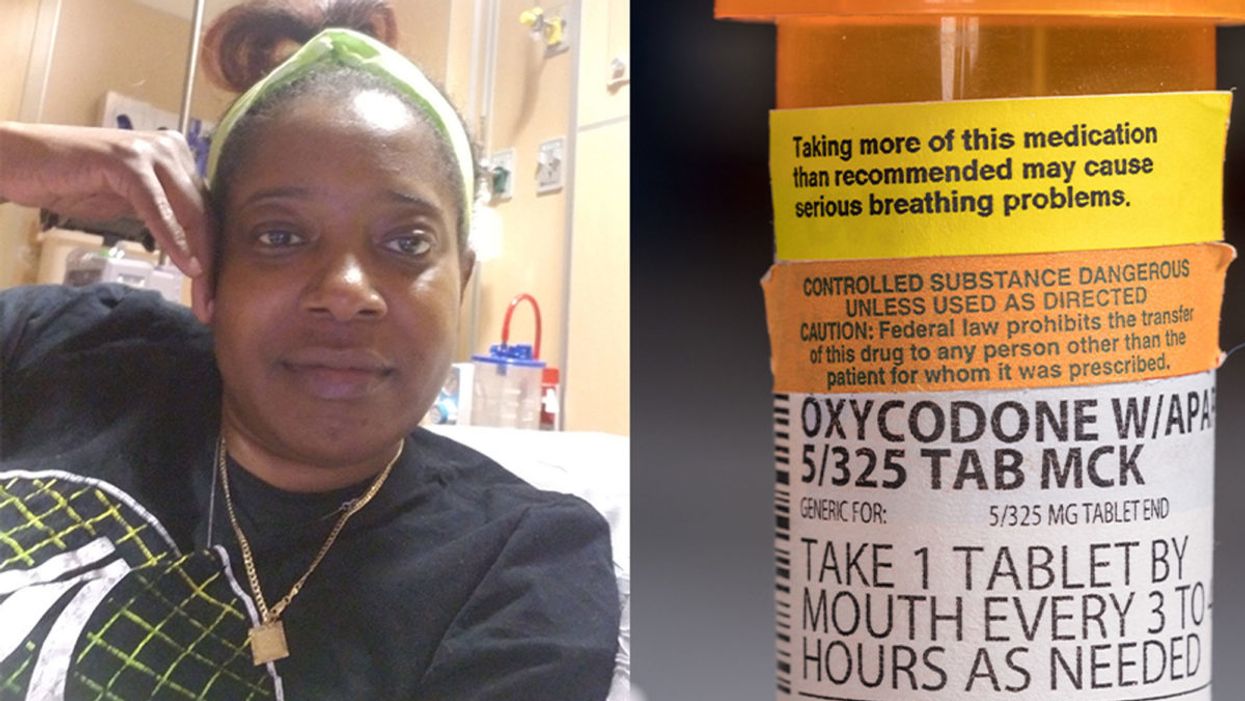

Sickle cell patient Bridgett Willkie found herself being labeled an addict when she sought an opioid prescription to control her pain.

"That throbbing you feel for the first minute after a door slams on your finger."

This is how Central Florida resident Bridgett Willkie describes the attacks of pain caused by her sickle cell anemia – a genetic blood disorder in which a patient's red blood cells become shaped like sickles and get stuck in blood vessels, thereby obstructing the flow of blood and oxygen.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was."

Willkie's lifelong battle with the condition has led to avascular necrosis in both of her shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. This means that her bone tissue is dying due to insufficient blood supply (sickle cell anemia is among the medical conditions that can decrease blood flow to one's bones).

"That adds to the pain significantly," she says. "Every time my heart beats, it hurts. And the pain moves. It follows the path of circulation. I liken it to a traffic jam in my veins."

For more than a decade, she received prescriptions for Oxycontin. Then, four years ago, her hematologist – who had been her doctor for 18 years – suffered a fatal heart attack. She says her longtime doctor's replacement lacked experience treating sickle cell patients and was uncomfortable writing her a prescription for opioids. What's more, this new doctor wanted to place her in a drug rehab facility.

"Because I refused to go, he stopped writing my scripts," she says. The ensuing three months were spent at home, detoxing. She describes the pain as unbearable. "Sometimes I just wanted to die."

One of the effects of the opioid epidemic is that many legitimate pain patients have seen their opioids significantly reduced or downright discontinued because of their doctors' fears of over-prescribing addictive medications.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was...Being treated like a drug-seeking patient is degrading and humiliating," says Willkie, who adds that when she is at the hospital, "it's exhausting arguing with the doctors...You dread them making their rounds because every day they come in talking about weaning you off your meds."

Situations such as these are fraught with tension between patients and doctors, who must remain wary about the risk of over-prescribing powerful and addictive medications. Adding to the complexity is that it can be very difficult to reliably assess a patient's level of physical pain.

However, this difficulty may soon decline, as Indiana University School of Medicine researchers, led by Dr. Alexander B. Niculescu, have reportedly devised a way to objectively assess physical pain by analyzing biomarkers in a patient's blood sample. The results of a study involving more than 300 participants were published earlier this year in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Niculescu – who is both a professor of psychiatry and medical neuroscience at the IU School of Medicine – explains that, when someone is in severe physical pain, a blood sample will show biomarkers related to intracellular adhesion and cell-signaling mechanisms. He adds that some of these biomarkers "have prior convergent evidence from animal or human studies for involvement in pain."

Aside from reliably measuring pain severity, Niculescu says blood biomarkers can measure the degree of one's response to treatment and also assess the risk of future recurrences of pain. He believes this new method's greatest benefit, however, might be the ability to identify a number of non-opioid medications that a particular patient is likely to respond to, based on his or her biomarker profile.

Clearly, such a method could be a gamechanger for pain patients and the professionals who treat them. As of yet, health workers have been forced to make crucial decisions based on their clinical impressions of patients; such impressions are invariably subjective. A method that enables people to prove the extent of their pain could remove the stigma that many legitimate pain patients face when seeking to obtain their needed medicine. It would also improve their chances of receiving sufficient treatment.

Niculescu says it's "theoretically possible" that there are some conditions which, despite being severe, might not reveal themselves through his testing method. But he also says that, "even if the same molecular markers that are involved in the pain process are not reflected in the blood, there are other indirect markers that should reflect the distress."

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years.

Willkie says she would welcome a reliable pain assessment method. Well-aware that she is not alone in her plight, she has more than 500 Facebook friends with sickle cell disease, and she says that "all of their opioid meds have been restricted or cut" as a result of the opioid crisis. Some now feel compelled to find their opioids "on the streets." She says she personally has never obtained opioids this way. Instead, she relies on marijuana to mitigate her pain.

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years: "It takes a while for things to translate from a lab setting to a commercial testing arena."

In the meantime, for Willkie and other patients, "we have to convince doctors and nurses that we're in pain."

Some people can eat red meat without negative health consequences, which may be due to variability between people's gut microbes.

In different countries' national dietary guidelines, red meats (beef, pork, and lamb) are often confined to a very small corner. Swedish officials, for example, advise the population to "eat less red and processed meat". Experts in Greece recommend consuming no more than four servings of red meat — not per week, but per month.

"Humans 100% rely on the microbes to digest this food."

Yet somehow, the matter is far from settled. Quibbles over the scientific evidence emerge on a regular basis — as in a recent BMJ article titled, "No need to cut red meat, say new guidelines." News headlines lately have declared that limiting red meat may be "bad advice," while carnivore diet enthusiasts boast about the weight loss and good health they've achieved on an all-meat diet. The wildly successful plant-based burgers? To them, a gimmick. The burger wars are on.

Nutrition science would seem the best place to look for answers on the health effects of specific foods. And on one hand, the science is rather clear: in large populations, people who eat more red meat tend to have more health problems, including cardiovascular disease, colorectal cancer, and other conditions. But this sort of correlational evidence fails to settle the matter once and for all; many who look closely at these studies cite methodological shortcomings and a low certainty of evidence.

Some scientists, meanwhile, are trying to cut through the noise by increasing their focus on the mechanisms: exactly how red meat is digested and the step-by-step of how this affects human health. And curiously, as these lines of evidence emerge, several of them center around gut microbes as active participants in red meat's ultimate effects on human health.

Dr. Stanley Hazen, researcher and medical director of preventive cardiology at Cleveland Clinic, was one of the first to zero in on gut microorganisms as possible contributors to the health effects of red meat. In looking for chemical compounds in the blood that could predict the future development of cardiovascular disease, his lab identified a molecule called trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). Little by little, he and his colleagues began to gather both human and animal evidence that TMAO played a role in causing heart disease.

Naturally, they tried to figure out where the TMAO came from. Hazen says, "We found that animal products, and especially red meat, were a dietary source that, [along with] gut microbes, would generate this product that leads to heart disease development." They observed that the gut microbes were essential for making TMAO out of dietary compounds (like red meat) that contained its precursor, trimethylamine (TMA).

So in linking red meat to cardiovascular disease through TMAO, the surprising conclusion, says Hazen, was that, "Without a doubt, [the microbes] are the most important aspect of the whole pathway."

"I think it's just a matter of time [before] we will have therapeutic interventions that actually target our gut microbes, just like the way we take drugs that lower cholesterol levels."

Other researchers have taken an interest in different red-meat-associated health problems, like colorectal cancer and the inflammation that accompanies it. This was the mechanistic link tackled by the lab of professor Karsten Zengler of the UC San Diego Departments of Pediatrics and Bioengineering—and it also led straight back to the gut microbes.

Zengler and colleagues recently published a paper in Nature Microbiology that focused on the effects of a red meat carbohydrate (or sugar) called Neu5Gc.

He explains, "If you eat animal proteins in your diet… the bound sugars in your diet are cleaved off in your gut and they get recycled. Your own cells will not recognize between the foreign sugars and your own sugars, because they look almost identical." The unsuspecting human cells then take up these foreign sugars — spurring antibody production and creating inflammation.

Zengler showed, however, that gut bacteria use enzymes to cleave off the sugar during digestion, stopping the inflammation and rendering the sugar harmless. "There's no enzyme in the human body that can cleave this [sugar] off. Humans 100% rely on the microbes to digest this food," he says.

Both researchers are quick to caution that the health effects of diet are complex. Other work indicates, for example, that while intake of red meat can affect TMAO levels, so can intake of fish and seafood. But these new lines of evidence could help explain why some people, ironically, seem to be in perfect health despite eating a lot of red meat: their ideal frequency of meat consumption may depend on their existing community of gut microbes.

"It helps explain what accounts for inter-person variability," Hazen says.

These emerging mechanisms reinforce overall why it's prudent to limit red meat, just as the nutritional guidelines advised in the first place. But both Hazen and Zengler predict that interventions to buffer the effects of too many ribeyes may be just around the corner.

Zengler says, "Our idea is that you basically can help your own digestive system detoxify these inflammatory compounds in meat, if you continue eating red meat or you want to eat a high amount of red meat." A possibly strategy, he says, is to use specific pre- or probiotics to cultivate an inflammation-reducing gut microbial community.

Hazen foresees the emergence of drugs that act not on the human, but on the human's gut microorganisms. "I think it's just a matter of time [before] we will have therapeutic interventions that actually target our gut microbes, just like the way we take drugs that lower cholesterol levels."

He adds, "It's a matter of 'stay tuned', I think."